7 things you didn’t know about Central Park

Although it’s one of the most visited city parks in the world, Central Park is chock-full of hidden spots and historic treasures that even native New Yorkers don’t know about. Designed by Fredrick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the 840-acre park has served as an oasis for city dwellers for over 150 years. Ahead, learn about some of Central Park’s lesser-known sites, from its waterfalls and whisper bench to a Revolutionary War-era cannon.

© Miesha Agrippa for 6sqft

1. The park’s 1,600 lampposts have “secret codes” to show the way to lost park goers.

On a beautiful spring day, it’s easy to get lost in Central Park’s 840 acres of greenery and gardens. But did you know the park’s lampposts can help you find your way? Designed by Beaux-Arts architect Henry Bacon in 1907, each of the park’s 1,600 lampposts has a set of numbers at its base, with the first two digits indicating the nearest street and the last two designating east or west. An odd number means west and an even number means east.

Photo by Eric Gross on Flickr

2. There are at least five waterfalls in Central Park. The water is the same as what you drink from your tap.

Five man-made waterfalls on the northern end of the park offer a peaceful respite from the chaos of the city. In the North Woods, find a flowing stream known as the “Loch,” which travels through the Ravine and under Glen Span and Huddlestone arches and connects to the Harlem Meer. Unlike the park’s other waterways, the Loch is partially fed by a natural watercourse, according to the Central Park Conservancy.

Photo courtesy of the Central Park Conservancy

3. The cannon at Fort Clinton actually came from the British warship H.M.S Hussar, which sunk in the East River during the Revolutionary War.

With views of Harlem Meer and the city’s east side skyline, Fort Clinton served as a strategic overlook during the War of 1812. Named after the city’s mayor at the time, Dewitt Clinton, the fortification and its original remains were retained during the construction of Central Park. A historic cannon and mortar can be found at the top that actually predate the War of 1812. They came from H.M.S. Hussar, a British warship that sank in the East River in 1778, and were later donated anonymously to Central Park in 1865.

The Revolutionary War-era cannon was moved to various locations in the park and was eventually installed at Fort Clinton in 1905. When staff from the Conservancy cleaned the cannon in 2013, they found it was still loaded with a cannonball and gunpowder, all of which have since been removed.

Photo via Wikimedia

4. The Blockhouse, built for the War of 1812, is Central Park’s second oldest structure.

Another relic from a war that never reached Manhattan, the Blockhouse is the oldest building in Central Park, after Cleopatra’s Needle. The Blockhouse was built in 1814 to defend against British troops, who never actually attacked New York City during the three-year battle. At its peak, the fort, which consists of a two-story bunker, held 2,000 New York militiamen. When this northern area was added to the park’s design in 1863, Olmsted and Vaux decided to leave the Blockhouse as a charming piece of history.

Photo by Valorian on Wikimedia

5. The park is home to a “whisper bench” in Shakespeare Garden.

Similar to the whispering walls of Grand Central, a “whisper bench” exists in Central Park. Named in honor of Charles B. Stover, a park advocate and co-founder of the University Settlement, the curved granite bench can be found in the four-acre Shakespeare Garden. If you sit on one end and whisper, the sound travels to the other side, creating perhaps a new way to share secrets in the era of social distancing.

Via Wikimedia

6. There’s a surveyor bolt put in place by the mastermind of the Manhattan Grid that remains unmarked.

John Randel Jr., the chief surveyor who designed the Manhattan street grid more than 200 years ago, traversed the city for about a decade to mark nearly 1,000 future intersections. Randel and his team faced criticism from New Yorkers during his project, with some destroying his markers, siccing dogs on him, and even hitting him with vegetables. Only one of Randel’s many bolts has been found at a location that originally marked Sixth Avenue and 65th Street but is now a part of Central Park. Embedded in a rock on the southern end of the park, the bolt’s location remains unmarked in order to preserve it, as well as create a treasure hunt for history and city planning buffs.

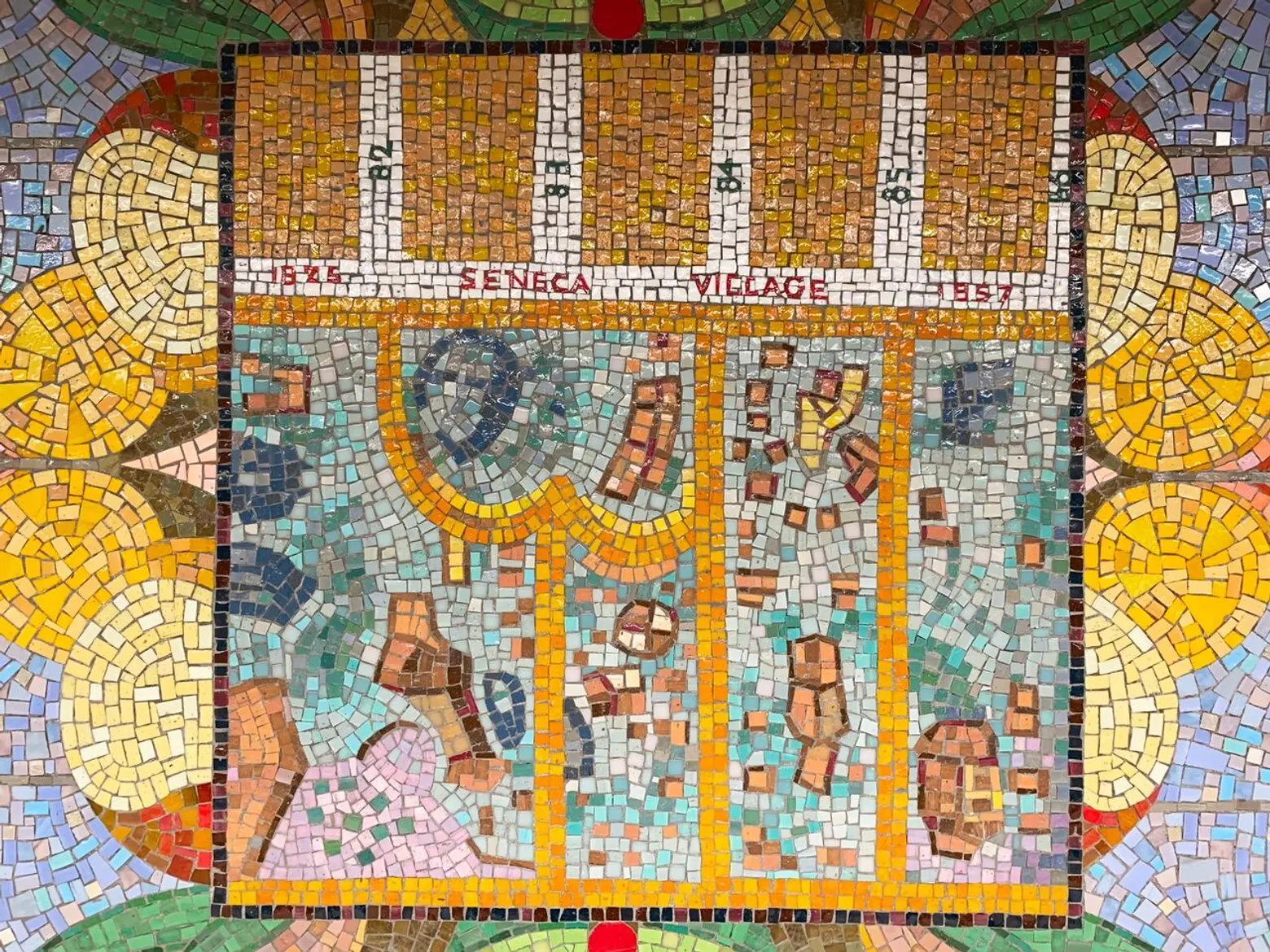

Mural translated from artist Joyce Kozloff’s “Parkside Portals” at 86th Street B, C station depicts a map of Seneca Village. Photo © 6sqft

7. One of the first African American communities in the city was razed to create Central Park.

About three decades before the creation of Central Park, the area was home to Seneca Village, a small settlement founded by free African American property owners, one of the first of its kind in New York. The community, which had three churches and a school, stretched between West 83rd and 89th Streets. By the 1840s, Irish and German immigrants moved to the area, making it one of the few integrated communities during this time.

In 1853, the city took control of the land through eminent domain and destroyed Seneca Village to make way for Central Park. The history of the community was largely ignored until 2011, when historians and archaeologists from the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History excavated six areas within the former village. The group found thousands of artifacts, including household items that revealed signs of middle-class life. Last year, the Central Park Conservancy launched an outdoor exhibit to teach visitors about Seneca Village. Learn more about Seneca Village here.

RELATED: