BIG Ideas: Bjarke Ingels Talks 2 WTC and Why Today’s Skyscrapers Lack Confidence

Helping to kick off the 2015 New York Times Cities for Tomorrow conference, Danish architect Bjarke Ingels—principal of Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), the firm responsible for 2 World Trade Center, Google HQ in Mountain View (with Thomas Heatherwick), the Dry Line and the pyramid-shaped “Via,” AKA 625 West 57th Street, among many others—talked “social infrastructure” with New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman. The baby-faced “starchitect 2.0” was his usual quotable and slightly mischievous self, yet, as always, provided plenty of insight on the topic at hand.

Well-known for his suggestion that “Architecture at its best is really the power to make the world a little bit more like our dreams,” Ingels offered his views on the ideal workspace design, what makes a memorable skyscraper and what some of his toughest challenges have been, in addition to speaking to the architect’s role in the social evolution of modern cities.

Since BIG is behind both 2 WTC and the Google HQ, there is a definite stake in creating the ultimate productive and innovative workplace. A notable highlight was Ingels’s take on the “inherent flaw” in the nascent modernism of the 1950s and its influence on the standards of office design. “For every question there was a universal answer, the perfect solution for everything [housework and kitchen design, for example].” Thusly did the perfect array of cubicles become the office landscape.

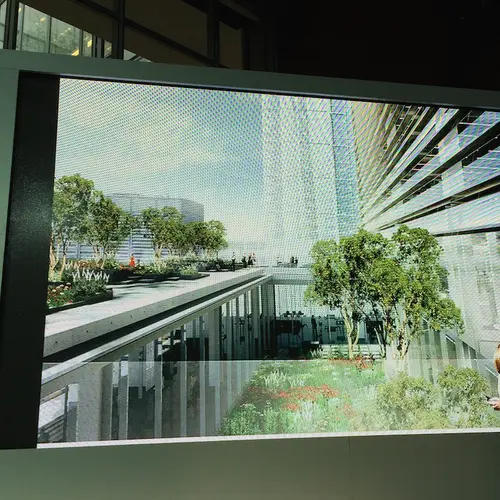

Rendering of office space at 2 World Trade Center.

Rendering of office space at 2 World Trade Center.

But the concept of this universal answer is slowly being replaced by the idea that if people are different, then workspaces—and residences—need to be different also. Instead, the design must provide diversity. Also important is the “visual and physical proximity” between colleagues that drives innovation. Architecture should invite interaction both physically and visually. The new ideal is a “flexible, dynamic workspace.”

When asked whether he actually likes the new 1WTC, Ingels takes the opportunity to weigh in on the supertall topic of skyscrapers: “In a city that invented the skyscraper, the skyscrapers that really stand the test of time are the skyscrapers that are the most confident–the ones that are a pure manifestation of a blatant idea.” Illustrating this confidence are the Grace Building and Lever House (Gordon Bunshaft/Natalie De Blois/SOM), the Seagram Building (Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson) and the Flatiron Building (Daniel Burnham), a “perfect extrusion of a triangular lot.”

He likens the towers that rose in the subsequent postmodern era to “generic extrusion with an interesting hat,” and in its aftermath, much of the “confidence was gone, every tower had to be a little bit insecure and to show that it was responding to its surroundings you had to, like, ‘mess it up.’” In fact, he is a fan of 1 WTC; he feels it shows some of that “blatancy of the big idea.”

Ingels conceded that 2 WTC would be a challenge to any architect–between the inherent emotional connections, its relationship to the flagship tower, security issues, diverse clients and much more. Yet the building is so important because, as he sees it, it is “the last piece in the revitalization of downtown Manhattan,” and it’s located in the “cradle of the skyscraper.”

Bjarke Ingels’ 57th Street pyramid.

Bjarke Ingels’ 57th Street pyramid.

Also memorable is his suggestion on how the architect handles the profession’s challenges (which he likens to a game of Twister). A “standard solution” (what he calls “typical Bob Moses”) doesn’t hold up once the diversity of human living and its many factors is added. It is up to the architect to find the “secret recipe that allows us to go beyond the standard solution.” How to do this? “Pile on more demands. Suddenly the standard solution doesn’t work anymore…by making the problem more difficult to solve, we escape the straitjacket of the standard solution.”

See the discussion on video here.

RELATED: