Cliffs Notes on New York’s Most Famous Storied Residential Buildings

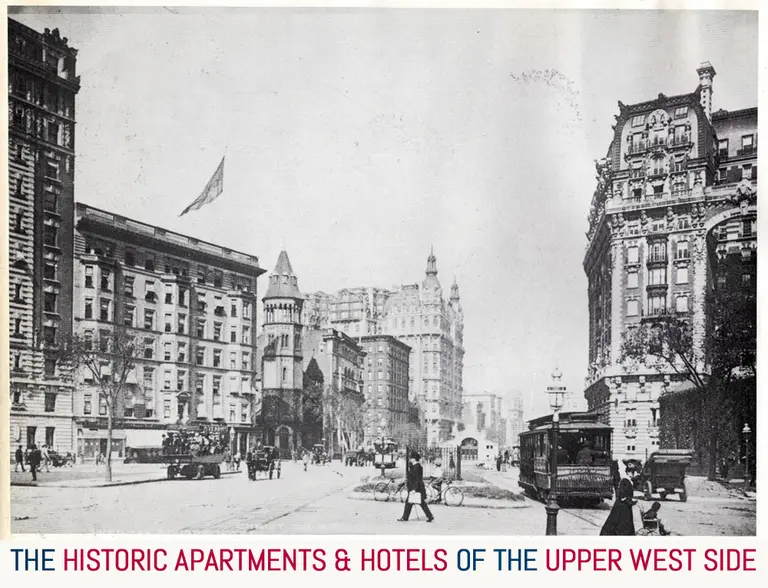

The newest apartment houses, be it now or some 150 years ago has always been of great interest to New York buyers and renters. And like today, their appeal make sell-outs as easy as pie. From Manhattan’s very first apartment building to those that followed a decade or so later, those initial projects continue to remain the city’s most coveted digs—not to mention the city’s most expensive. But what stands out among these famous buildings as the years passed was the introduction of not-yet-available services—ranging from running water and elevators to electricity and communal amenities. Whether we are talking about the Dakota or the luxurious the Osborne Flats, learn why these century-plus-old buildings continue to enchant the rich, the famous, and the rest of us.

Image via The Bowery Boys

Image via The Bowery Boys

Stuyvesant Flats

Did you know that Manhattan’s first ever apartment was built in 1870? A residential project undertaken by developer Rutherford Stuyvesant and designed by architect Richard Morris Hunt, this residence was the first form of ‘acceptable’ communal living for the city and was. Known then as the Stuyvesant Flats, and located at 142 East 18th St. near Third Avenue and set Mr. Stuyvesant back $100,000.

The five-story, 20-unit building, of which four were artists’ studios. Modeled after typical multi-use French flats where storekeepers set up their shops at a building’s street level, they were all the rage as far back as the 17th century in France. Though it didn’t have an elevator, it did feature running water, which was somewhat unusual for the time—but in later years, heat and electricity were added.

The building actually remained fully occupied until its demolition in 1958 in order to make way for a new apartment house called Gramercy Green. Since then, Gramercy Green has remained a rental development and currently, Douglas Elliman has listings on the market ranging from $2,895 to $4,995 per month.

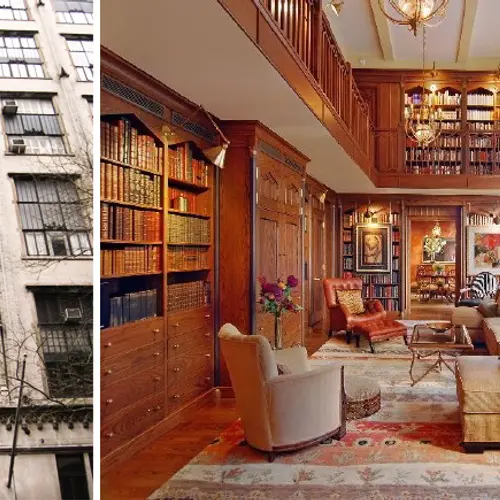

Image courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

Image courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

Nearly a decade after Stuyvesant debuted his much-talked-about apartment, the nine-story Dakota, began construction in 1880. Set majestically on the northwest corner of Central Park at 72nd Street, it was designed by architect Henry J. Hardenbergh (who went on to design the Plaza Hotel in 1907) at the request of Edward Clark, one of founders of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. The now legendary Dakota was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

Built around a central courtyard, the arched main entrance with a porte cochère was large enough for the horse-drawn carriages to pass through so passengers could disembark, sheltered from the weather. It had 65 apartments with four to 20 rooms each (623 rooms in all and no two alike) and could be accessed by both staircases and elevators. Separate staircases and elevators were used to access apartment kitchens … likely designed for servants to go unnoticed. Electricity was generated by an in-house power plant and there was central heating throughout.

Image courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

Image courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

The Dakota had a large public dining hall with an inlaid marble floor, an enormous wood-burning fireplace and a carved, quartered-oak ceiling at ground level, but meals could also be transported to apartments by dumbwaiters. An adjacent private dining room was outfitted with mahogany and large beveled-glass windows. The top floors were delegated to servant’s quarters as well as laundry and storage rooms. Above those rooms was a roof garden and playroom. Private croquet lawns and a tennis court were set behind the building.

Main rooms in the French-styled apartments, such as parlors and master bedrooms, were created to face the street and the auxiliary rooms (i.e., formal dining rooms and kitchens) overlooked the courtyard. The result was significant because fresh air came from both sides, which was a relatively novel approach at the time. Quite a few featured 49-foot-long parlors, wood-burning fireplaces and 12- to 14-foot-high ceilings. Floors were inlaid with mahogany, oak and cherry with one exception: Mr. Clark requested that some of his floors be inlaid with sterling silver. (Ironically, Mr. Clark died before the building was completed.)

A number of movies, including Rosemary’s Baby and Vanilla Sky, were filmed here, only using the Dakota’s exteriors since no filming was allowed inside. Of course, it goes without saying – the Dakota is world famous as the last home of John Lennon. Taking up residence in 1973, he resided there until he was shot and killed by Mark David Chapman in 1980. Obviously a magnet for celebrities over the years, former residents included Leonard Bernstein, Judy Garland, Judy Holliday, Jose Ferrer, Rosemary Clooney, Lillian Gish, Boris Karloff, Rudolf Nureyev, Gilda Radner, Jason Robards, and Zachary Scott.

As you’d expect, servants’ quarters and such were later converted to apartments. Originally built as a rental (and a sold out one at that), the Dakota converted into a co-op in the early 1960s.

The ornate lobby of the Osborne Flats

The ornate lobby of the Osborne Flats

With its Byzantine lobby ornately done up in mosaic tiles, glazed terracotta “Della Robbia” panels cover the walls, Tiffany glass, a red-, blue- and gold-leaf coffered ceiling, elaborate John La Farge murals, a August Saint-Gaudens sculpture, plaques etched with nudes and floral garlands and multi-colored Italian marble (some of which is used for the wainscoting and arched niches with benches), the Romanesque Revival cum Italian Renaissance-style Osborne Flats at 205 West 57th Street and Seventh Avenue is, appropriately, only further boosted by its location catty-corner from Carnegie Hall.

Built at the request of stonemason Thomas Osborne, and designed by architect James Edward Ware in 1883 as a rental, it was completed in 1885 (another story was added in 1889 and in 1906, an annex designed by the Alfred S. G. Taylor and Julien Clarence Levi was added on the building’s west side in 1906) for $1.209 million. Unfortunately, soon after the residence opened, Osborne declared bankruptcy and then sold the building to John Taylor who had originally owned and sold the land to Osbourne. But misfortune continued and by 1888, Taylor’s estate lost the building to foreclosure and it was then purchased by a relative for a bit less than the original cost of construction. in 1961, the Osborne converted to a co-op after its residents purchased it for $2.5 million, and it was designated a New York City landmark in 1991.

NY Knicks president Phil Jackson recently purchased a $5 million home here. Image courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

NY Knicks president Phil Jackson recently purchased a $5 million home here. Image courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

With just four apartments (including duplexes) to a floor, most featured grand parlors, dining rooms, secret passageways for servants to go unnoticed between the front door to the kitchen and servant quarters. They all boasted 14-foot ceilings, oak parquet floors with banded edgings, carved and tiled (some with bronze mantles) wood-burning fireplaces, crystal chandeliers, Tiffany windows and oak and mahogany woodwork. All the bedrooms and private baths were either up or down a small flight of steps.

Famous past residents included Leonard Bernstein (while writing West Side Story) who then sold it to actor Larry Storch, who in turn sold it to musician Bobby Short. Among the list of red-carpet residents was pianist Van Cliburn and actors Lynn Redgrave, Shirley Booth, and Imogene Coca. Actor Gig Young also lived at the Osbourne with his new wife, Kim Schmidt, but in the fall of 1978, he shot her to death and then turned the gun on himself.

Facing Fifth Avenue at Central Park South, The Plaza Hotel opened in 1907. Described as the greatest hotel in the world, it was developed by financier Bernhard Beinecke, hotelier Fred Sterry and Harry S. Black, who was the president of the Fuller Construction Company. Incidentally, it was Fuller Construction who convinced cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post to give up her townhouse off Fifth Avenue at 92nd Street in exchange for a 54-room penthouse (New York’s first and largest) atop a new apartment house the company wanted to develop.

Purchasing a 15-year-old hotel of the same name on the site, they set out to replace it with a new 19-story French Renaissance château-style hotel designed by Hardenbegh. Designated a New York City Landmark in 1969, The Plaza was listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1978 and National Historic Landmark in 1986.

Marble finishes were everywhere, as were vaulted stained-glass windows, solid mahogany doors and 1,650 crystal chandeliers. Custom-manufactured Irish Linens, Swiss Organdy curtains and gold-encrusted china represented the short list of luxury add-ons. Two years and $12.5 million later, they realized their dream – with Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt checking in as its first guests. Originally conceived as a residence for wealthy New Yorkers, it was available to other guests on a nightly basis. Rates started at $2.50 per night.

An interior shot of Tommy Hilfiger’s Plaza penthouse. Image courtesy of Dolly Lenz Real Estate

An interior shot of Tommy Hilfiger’s Plaza penthouse. Image courtesy of Dolly Lenz Real Estate

Conrad Hilton bought the hotel for $7.4 million in 1943, but he covered the Palm Court’s magnificent stained-glass ceiling to add air-conditioning. The Childs Company (a restaurant chain quite famous at the time) purchased it for $1.1 million shares of Childs common stock in 1955. Donald Trump purchased the hotel for $390 million in 1998, but sold it a few years later for $325 million – but not before choosing the ballroom as the venue for his wedding to Marla Maples in 1993. Other celebs tied the knot in that ballroom, including Eddie Murphy and Nicole Mitchell in 1993 and Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones in 2000.

The first time a film used the hotel as one of its main locations was in 1959 for was Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Before long, the Plaza took center stage in several other films, including Plaza Suite, The Way We Were, Barefoot in the Park, Funny Girl, They All Laughed and Home Alone 2: Lost in New York.

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright called it home from 1954 to 1959 and the Beatles stayed at the Plaza during their first visit to the US in February 1964. To celebrate the success of “In Cold Blood” and honor Katherine Graham of the Washington Post, author Truman Capote hosted his legendary (and masked) Black & White Ball in the Grand Ballroom in 1966.

Currently, CityRealty has several units listed at this iconic landmark, including Tommy Hillfiger’s penthouse pad for $80 million.

Built between 1899 and 1904 by the eccentric music and animal lover William Earl Dodge Stokes and designed by the architectural firm of Graves and Duboy, the Ansonia Apartments on Broadway and 73rd Street were equipped with luxuries such as electric stoves, hot and cold water, freezers, and an early version of central air-conditioning. It had very thick walls, installed to protect against fire, which in turn made the Ansonia the most soundproof building in the city. As a result, many of its famous tenants were musicians including Enrico Caruso, Igor Stravinsky, Arturo Toscanini, Ezio Pinza, Lily Pons, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Gustave Mahler and Yehudi Menuhin. Theatrical notables include Sol Hurok, Florenz Ziegfeld, Sarah Bernhardt, Bille Burke, Moss Hart, Tony Curtis and Paul Sorvino and famous writers such as Elmer Rice, and Theodore Dreiser also called the Ansonia home.

Apartment 3-79‘s jaw-droppingly beautiful terrace. Image courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

Apartment 3-79‘s jaw-droppingly beautiful terrace. Image courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

It was also Babe Ruth’s first home in New York after the owner of the Boston Red Sox “sold” him to the Yankees. Living the life of a bachelor, Babe Ruth sowed his wild oats at The Ansonia, then New York’s most elegant residential hotel. Legend has it that he chased women up and down the halls and had one employee dedicated to sorting his fan mail. “Keep the dough and the pictures of the broads, and throw the rest out,” were his reputed instructions.

The building originally contained 340 suites with a total of over 1,400 rooms (which have since been subdivided), as well as ballrooms, tea rooms, writing rooms, a lobby fountain with live seals, and the world’s largest indoor pool in the basement. Stokes also kept a private farm on the roof with live chickens, ducks, goats and a small bear.

Upper West Side-seeking buyers can contact Ansonia Realty LLC to get a gander at several units that are currently on the market.

Image courtesy of Sotheby’s Realty

Image courtesy of Sotheby’s Realty

Another building of historic proportions is the Hotel des Artistes. A neo-Gothic-style building with Tudor detail on 67th Street off Central Park West, it remains nothing less than illustrious. Originally developed in 1915 by Walter Russell and designed by architect George Mort Pollard, it was developed as a co-op with some artists’ studios for rent. Understandably, the studios were eventually converted to co-ops.

Most of the homes were small “kitchen-less” duplexes with double-height living rooms and enormous light-filled windows, beamed ceilings, wood-burning fireplaces and balcony bedrooms. English Renaissance-style paneling was used for the living and dining rooms.

Impressive extras at the time of its completion in 1917 included two restaurants, a squash court, a swimming pool, a sun parlor a theater and a ballroom. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1985, the building still offers its residents use of the pool and squash court, plus a rooftop terrace, round-the-clock doormen and elevator operators. Until recently, it housed Café des Artistes, one of New York’s most beloved eateries – but was replaced with a new eatery called Leopard des Artistes.

Notable past residents included Isadora Duncan, George Balanchine, Rudolph Valentino, Fannie Brice, Noel Coward, Fannie Hurst, Norman Rockwell and former New York City mayor John V. Lindsay.