Kleindeutschland: The History of the East Village’s Little Germany

Before there were sports bars and college dorms, there were bratwurst and shooting clubs. In 1855, New York had the third largest German-speaking population in the world, outside of Vienna and Berlin, and the majority of these immigrants settled in what is today the heart of the East Village.

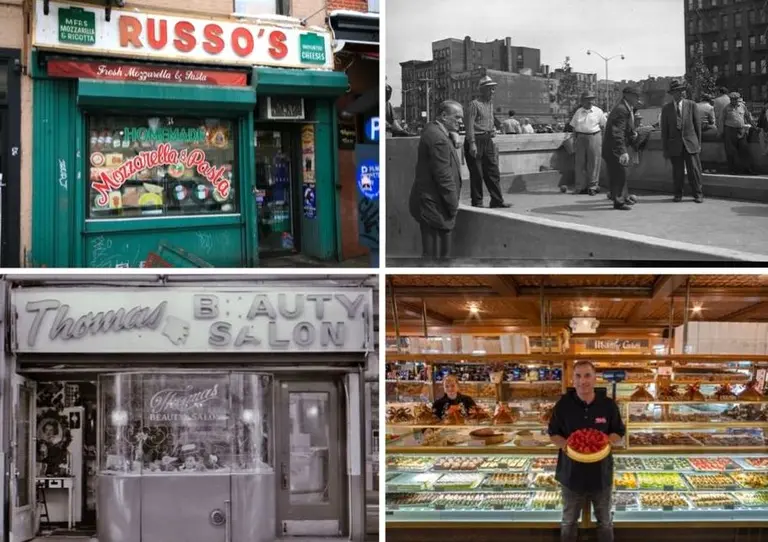

Known as “Little Germany” or Kleindeutschland (or Dutchtown by the Irish), the area comprised roughly 400 blocks, with Tompkins Square Park at the center. Avenue B was called German Broadway and was the main commercial artery of the neighborhood. Every building along the avenue followed a similar pattern–workshop in the basement, retail store on the first floor, and markets along the partly roofed sidewalk. Thousands of beer halls, oyster saloons, and grocery stores lined Avenue A, and the Bowery, the western terminus of Little Germany, was filled with theaters.

The bustling neighborhood began to lose its German residents in the late nineteenth century when Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe move in, and a horrific disaster in 1904 sealed the community’s fate.

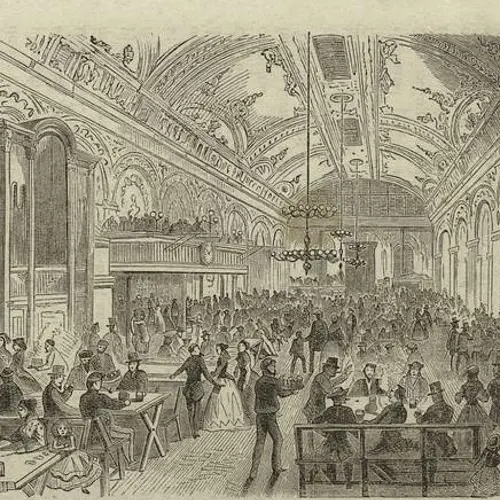

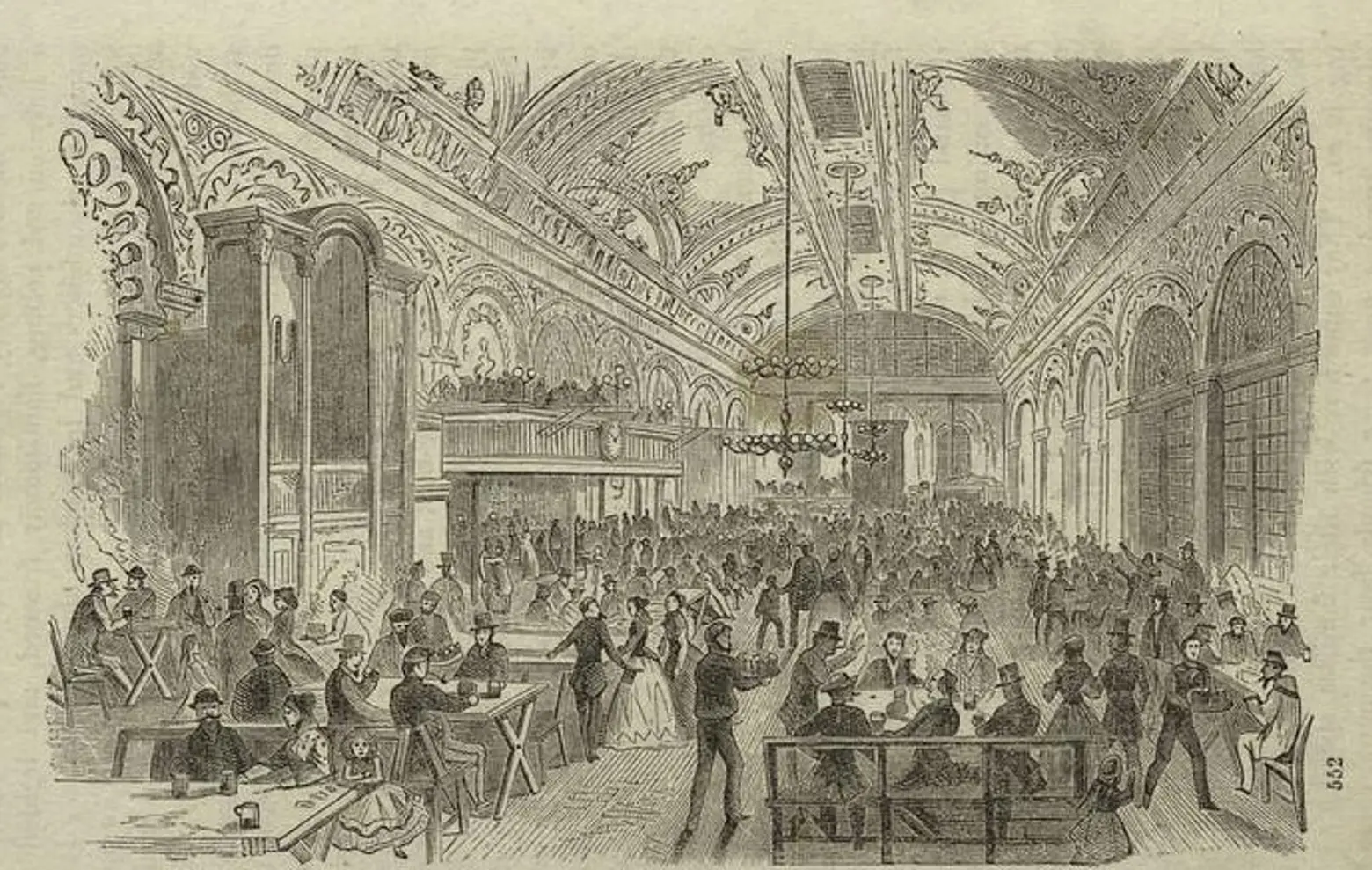

Inside the Atlantic Garden beer hall, via NYPL

German immigrants began arriving in the U.S. in large numbers in the 1840’s. Unlike some other immigrant groups, the Germans were educated and had skilled crafts, mainly in baking, cabinet making, and construction. They brought with them their guild system, which evolved into trade unions, eventually giving rise to the general labor-union movement. And they created their own banking and insurance companies, like the German-American Bank and the Germania Life-Insurance Comapny, now the Guardian Life Insurance Company. Little Germany also became the first non-English-speaking immigrant community in the country to retain the language and customs of its homeland.

By 1845, Kleindeutschland was the largest German-American neighborhood in the city, and by 1855 its German population had more than quadrupled, becoming the most heavily populated area in the city by 1860. Though all of New York’s immigrant groups tended to settle in specific neighborhoods, the Germans stuck together more so than many other. They even chose to live with those from their distinct section of Germany; those from Prussia accounted for almost one-third of the city’s German population.

A typical stretch of rowhouses on East 7th Street; via GVSHP

A typical stretch of rowhouses on East 7th Street; via GVSHP

As Little Germany’s population was exploding, more housing stock was necessary to accommodate the new residents. According to the East Village/Lower East Side Historic District designation report, small, two- or three-story rowhouses were subdivided to hold at least eight families, with two households on each floor including the basement and attic. By the 1860’s, another solution was developed, which was to build multi-family tenements, soon becoming the staple in immigrant communities.

Beer gardens were the social meeting places of Little Germany, where residents young and old would gather. One of the most popular was the Atlantic Garden on the Bowery. Also a music hall, it was established by William Kramer in 1858 and catered to the crowd from the neighboring Bowery Theatre. The Theatre was originally constructed as the New York Theatre in 1826, but Germans Gustav Amberg, Heinrich Conried (a director of the Metropolitan Opera), and Mathilde Cottrelly (a stage actress, singer, and producer) converted it to the Thalia Theatre in 1879, offering mainly German performances.

Social clubs and singing societies were known as Vereines, and were scattered throughout the neighborhood. Located at 28 Avenue A was Concordia Hall, a club house and ballroom. In addition to hosting political and social groups, it was the meeting spot of a music society, two men’s choruses, and the German-American Teachers Association.

Another popular meeting spot was the German-American Shooting Society Clubhouse at 12 St. Mark’s Place. Built in 1889 by William C. Frohne in the German Renaissance Revival style, the building was home to 24 shooting clubs, dedicated to target practice and marksmanship. The site also had a saloon, restaurant, an assembly room, lodging spaces, and a bowling alley in the basement. Along St. Mark’s Place, what was then an upscale residential thoroughfare, were many other social clubs, such as the Harmonie Club and the Arion Society.

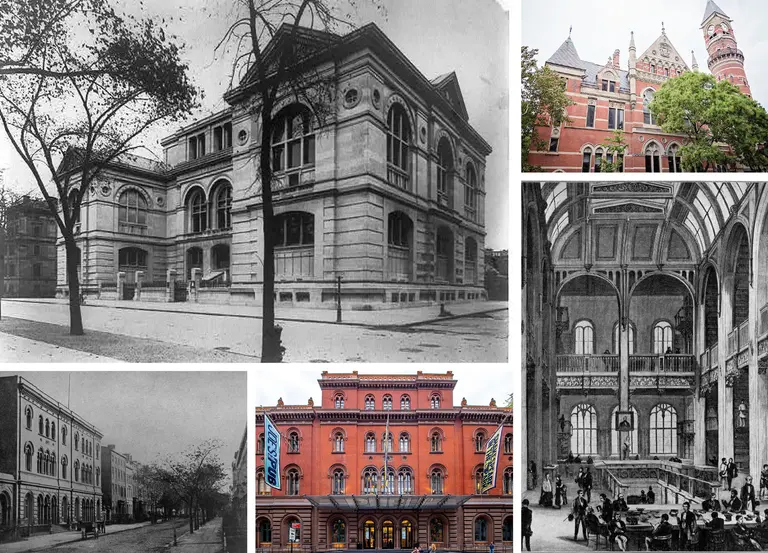

Germania Bank Building

Germania Bank Building

The Germania Bank Building is a reminder of Kleindeutschland that has been making recent headlines. Located at 190 Bowery, and built in 1899 in the Renaissance Revival style by German architect Robert Maynicke, it was the third location of the Germania Bank, founded in 1869 by a group of German-born businessman. Maynicke attended Cooper Union and worked for the noted architect George B. Post before co-founding the firm Maynicke & Franke in 1895. The bank building is considered one of his most important designs.

In 1966, the bank sold the building to photographer Jay Maisel for $102,000, who has been using the massive space as a single-family home. Just last month, though, Maisel sold the building, famously covered in graffiti, to real estate investor Aby Rosen for an undisclosed amount (though it’s speculated the price reached $50 million), and many believe condos are on the way.

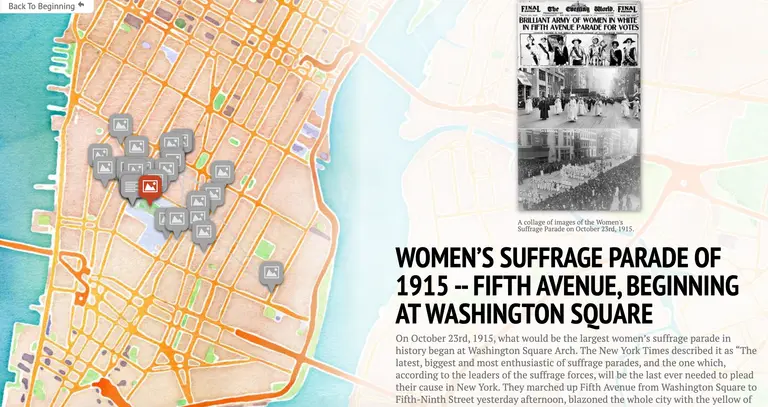

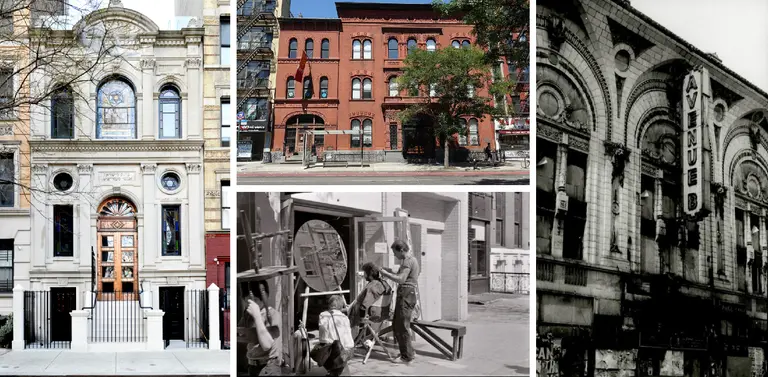

The Ottendorfer Library (left) and the Stuyvesant Polyclinic (right)

The Ottendorfer Library (left) and the Stuyvesant Polyclinic (right)

One of the most prominent and wealthy members of the Little Germany society was Oswald Ottendorfer, the owner and editor of the Staats-Zeitung, New York’s largest German-language newspaper. He was led the German Democracy party, which helped Fernando Wood recapture the mayor’s office in 1861 and elect Godfrey Gunther as mayor in 1863. But Ottendorfer’s legacy is still very much alive in the East Village, thanks to two public buildings he funded for the community that today are landmarked structures–the Ottendorfer Library and the Stuyvesant Polyclinic.

Oswald and his wife Anna were quite philanthropic and thought that bringing education and medical care to the neighborhood would help immigrants transition to their new life in New York. The Freie Bibliothek und Lesehalle, or Free Library and Reading Room, was designed by German-born architect William Schickel in the Queen Anne and neo-Italian Renaissance styles. When it opened in 1884, it was New York’s first free public library, and half of the 8,000 books were in German, while the other half were in English. It still functions as a vibrant community library today.

Adjacent to the library, and designed in a complementary style by William Schickel, the Stuyvesant Polyclinic was originally known as the German Dispensary (‘dispensaries’ were community health clinics ). It also opened in 1884 and offered medical care to the poor for low or no cost. Just below the building’s cornice are the busts of famous physicians throughout time. According to GVSHP, “The building was designated a New York City Landmark in 1976, and in 2008 it underwent a renovation for its new commercial tenant.”

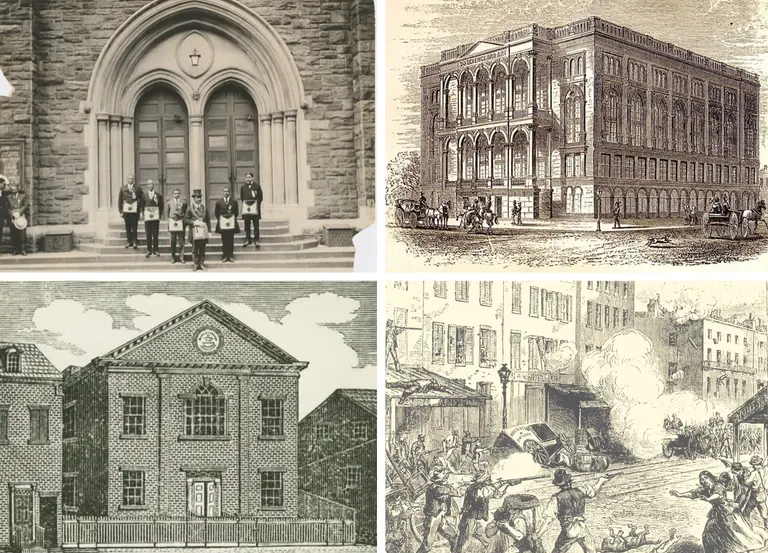

German Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. Mark, now the Community Synagogue

German Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. Mark, now the Community Synagogue

Around the turn of the century, Germans began to move out of the East Village, but a tragedy in 1904 is considered the symbolic end of Kleindeutschland…

In 1846, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. Matthew, which already existed in Lower Manhattan, established a branch at 323 East 6th Street. The Renaissance Revival building was completed in 1848 and became known as the German Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. Mark. On the morning of June 15, 1904, women and children who belonged to the church boarded the General Slocum steamship to take a Sunday visit to the Locust Grove Picnic Ground on Eatons Neck, Long Island. But soon after beginning its journey, the ship caught fire and burned completely in the East River in less than 15 minutes. Out of the 1,300 passengers on board, 1,000 perished. The disaster was the greatest loss of civilian life in New York until September 11th.

But where did Kleindeutschland’s Germans go? Find out next week in the second half of our German history series.

Images courtesy of Wiki Commons unless otherwise noted; Lead image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York