Living Breakwaters: An Award-Winning Project Brings ‘Oyster-tecture’ to the Shores of Staten Island

Image courtesy of SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE PLLC

We know what you’re thinking: what is oyster-tecture, anyway? Just ask Kate Orff, landscape architect and the founding principal of SCAPE Studio. SCAPE is a landscape architecture and urban design office based in Manhattan and specializing in urban ecology, site design, and strategic planning. Kate is also an associate professor of architecture and urban design at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, where she founded the Urban Landscape Lab, which is dedicated to affecting positive social and ecological change in the joint built-natural environment.

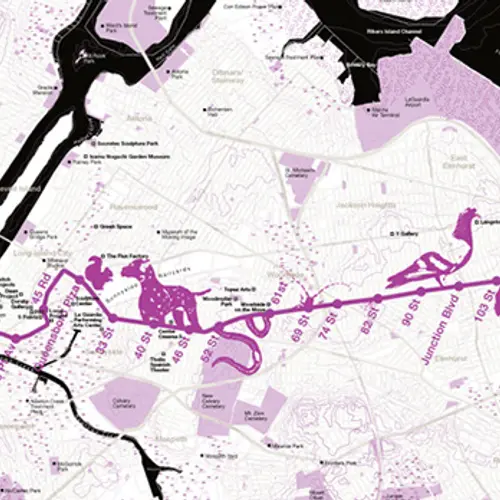

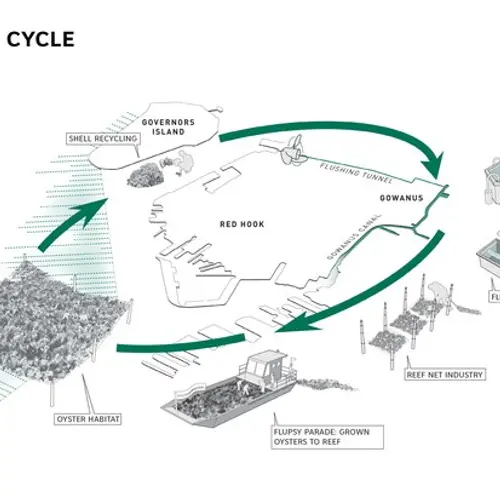

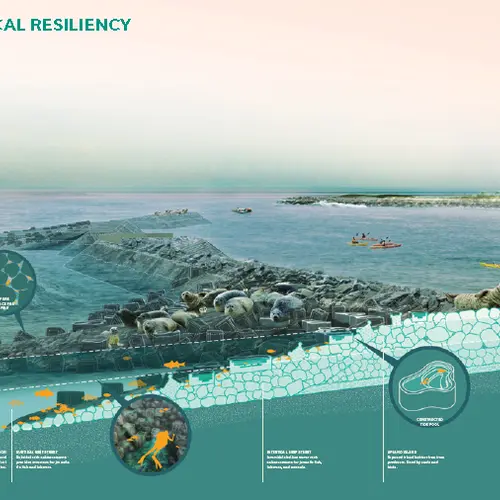

But the Living Breakwaters project may be the SCAPE team’s most impactful yet. The “Oyster-tecture” concept was developed as part of the MoMA Rising Currents Exhibition in 2010, with the idea of an oyster hatchery/eco-park in the Gowanus interior that would eventually generate a wave-attenuating reef in the Gowanus Bay. Describing the project as, “a process for generating new cultural and environmental narratives,” Kate envisioned a new “reef culture” functioning both as ecological sanctuary and public recreation space.

Oyster-tecture model at MoMA “Rising Currents” exhibition, 2010. Image courtesy of SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE PLLC

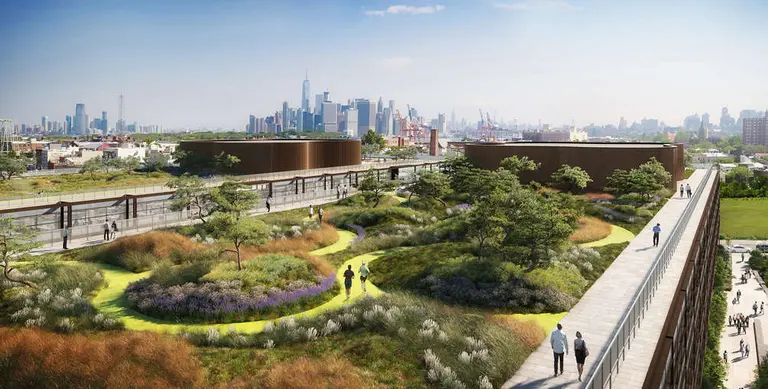

To study the concept’s feasibility, the team developed a pilot project for the SIMS municipal recycling center at the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal in Sunset Park (the facility’s new building was designed by another female starchitect, Annabelle Selldorf), a site for processing metal, glass, and plastic. Working in tandem with the facility’s expansion plans, SCAPE redesigned a 100-foot portion of the pier, retrofitting the existing infrastructure with a concrete matrix hospitable to species recruitment.

The purpose was to create “habitat hubs” for marine ecosystems without interfering with working industrial piers; ECOncrete and recycled “fuzzy rope” (frayed polyethylene rope) were used to provide habitats for mussels, barnacles, and sponges, while accommodating SIMS’ industrial requirements. Treating SIMS as a part of the ecology, SCAPE saw this pilot project as a way for the facility’s activity to be able to contribute to the site’s remediation–using, for example, recycled glass as the substrate for intertidal pools–as well as to research the possibilities for biological remediation at an active industrial site.

The next level

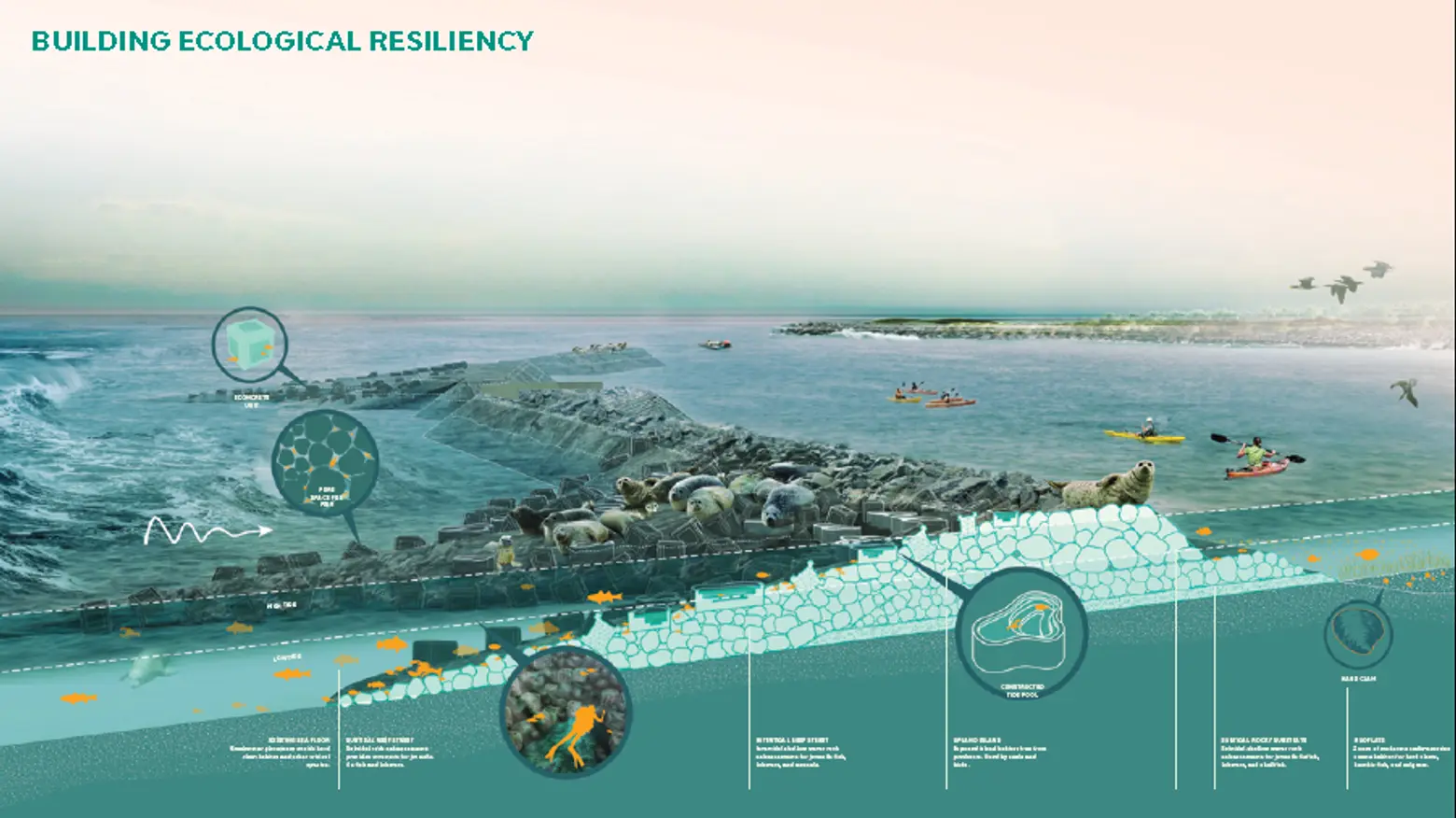

“The Living Breakwaters project combines coastal resiliency infrastructure with habitat enhancement techniques and community engagement, deploying a layered strategy that links in-water protective forms to on-shore interventions. We aim to mitigate the risk to humans from periodic weather extremes, improve the quality of our everyday lives, and rebuild our ecosystem.”

http://vimeo.com/91648619

Those are some outstanding goals, but as the project director of the Living Breakwaters project, 2014 was an outstanding year for Kate and her team. A–no pun intended–watershed event came when, as part of a larger team, the SCAPE team introduced the Living Breakwaters project for the HUD-sponsored Rebuild By Design contest, part of the President’s Hurricane Sandy rebuilding task force; it was among the six winning projects, which resulted in a $60 million implementation grant to build the protective reef structures. The SCAPE team and the project were also the 2014 recipients of the Buckminster Fuller Challenge Award grand prize, a $100,000 award to support the development and implementation of one outstanding strategy for solving some of humanity’s most pressing problems.

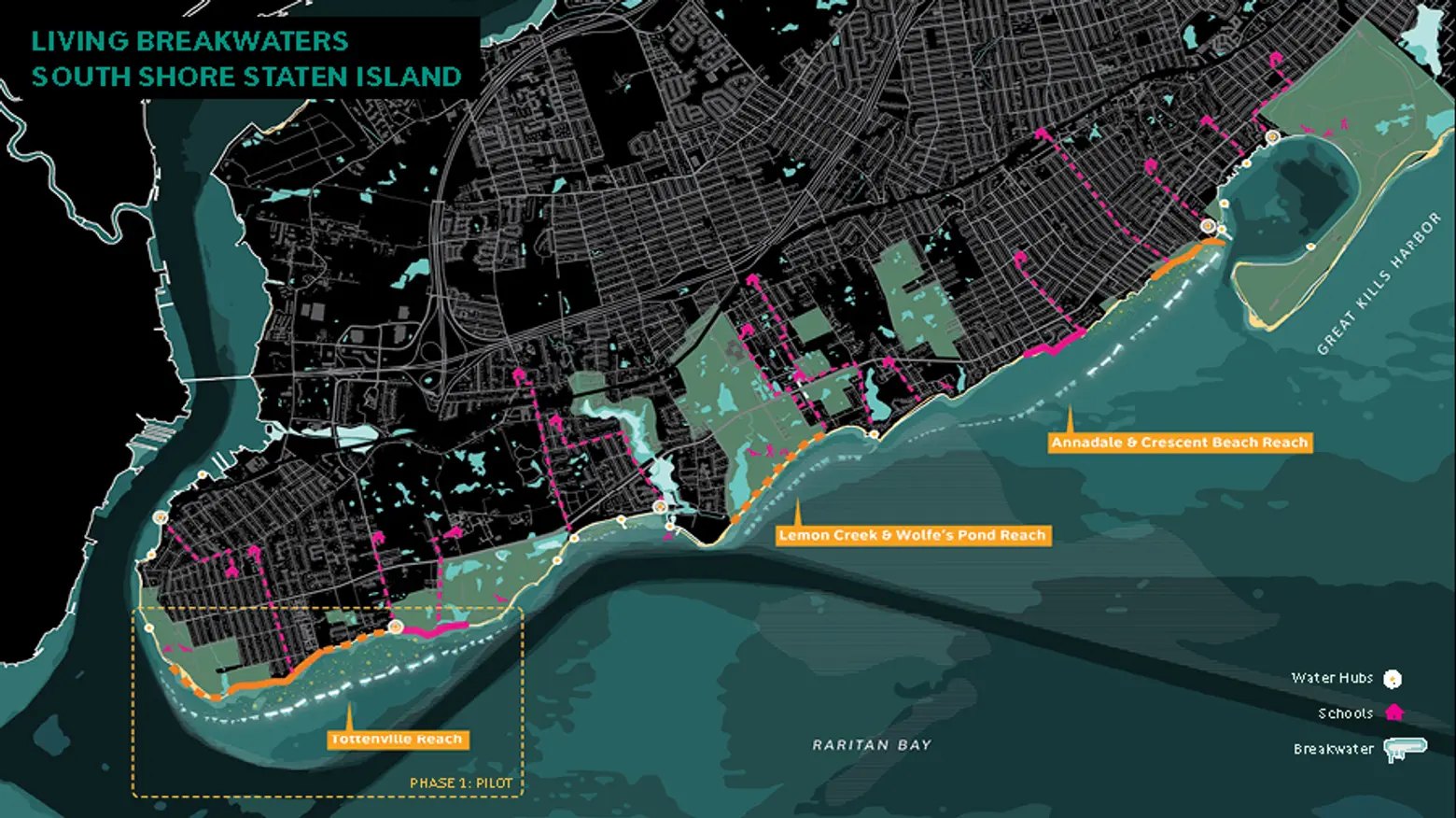

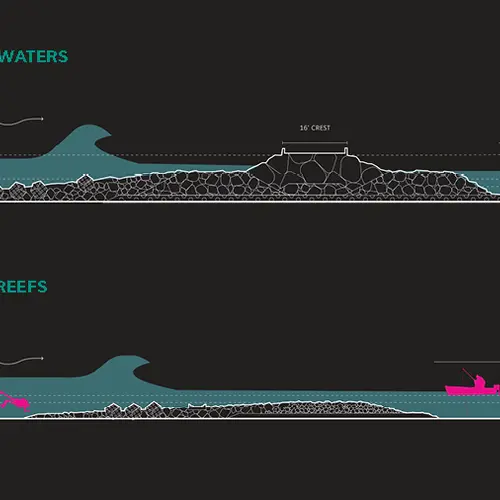

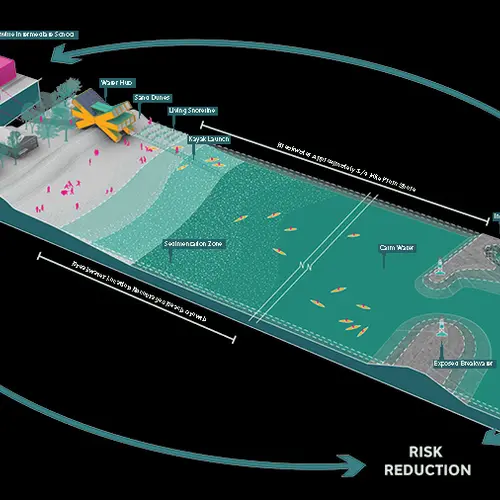

For the Living Breakwaters project, the team envisioned the “rebuilding of oyster habitats at strategic locations along the coastline for wave attenuation.” It would also help to “engage the cultural and social element of the city,” creating a “blue park.” The original oyster-tecture idea was developed into a “more complete system, relying minimally on the oyster and more on the expanded habitat potential of other shellfish and the creation of breakwaters through specialized concrete installations,” like the SIMS pilot project. The proposed pilot project in Tottenville, at the southernmost tip of Staten Island, uses a layered system of breakwaters constructed of ecologically engineered concrete to attenuate wave action, create habitats for juvenile fish, and provide calm waters for recreation. The location was chosen because of the area’s deep cultural roots in oystering and fishing, as well as its potential as a waterfront recreation area.

Engaging “the cultural and social element of the city”

Image courtesy of SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE PLLC

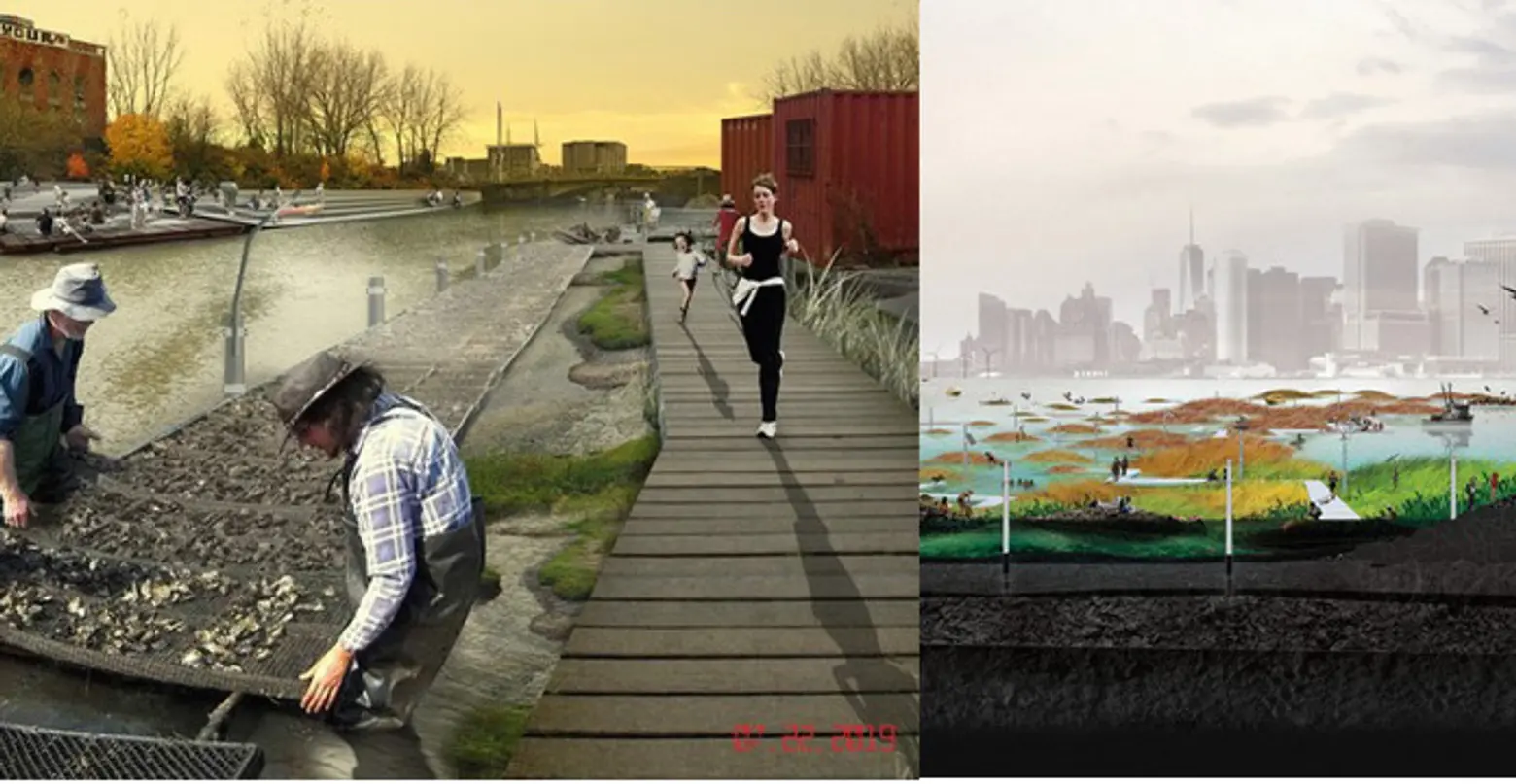

The Tottenville pilot will be used to study the ecological benefits, wave reduction impacts, and the economic and recreational potential of the project–as well as to offer those benefits to the community right now. The idea is to embrace the water and its economic and recreational opportunities, using shallow water landscapes to stabilize the shore and rebuild diverse habitats through “education, engagement, and the expansion of a water-based recreational economy.” The Billion Oyster Project, for example, teaches middle and high school students about oysters and the ecology and economy of local marine environments.

A landscape architect’s view

Kate Orff of SCAPE. Image courtesy of SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE PLLC

A new PBS television series, EARTH: A New Wild features a segment on Kate’s work with oyster-tecture, covering the regrowth of the area near the Bush Terminal Pier. At a preview screening of the program, accompanied by conservation scientist and Emmy-nominated host Dr. M. Sanjayan, Kate addressed questions on past projects and the upcoming Tottenville project. In discussing the concept’s testing grounds thus far, she noted the resulting intertidal landscape, a rarity in New York Harbor: “It’s a true moment of intertidal gradient…where this incredible mixture and diversity of species can take hold and, as shown in the film, this begins to create a structural habitat for mussels and oyster growth, which then begets other species.” She mentions seeing horseshoe crabs, native to the east coast, but with dramatically declining numbers; they are a “keystone species”–like the oyster–whose eggs are then food for migratory birds.

Image courtesy of SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE PLLC

On the integration of design: “I’m a landscape architect, which underscores a message..trying to find that theme, trying to understand how human ecology can come together…with design and with engineering and with planning–and with happy activists [she mentions a program segment on Mexican wetlands]…we can make our way through this period and find moments of hope.”

Instead of utopian visions, a hopeful spark

An audience member asks about the reality of sustaining the oyster beds and the actual feasibility of such an ambitious project, and what it can actually accomplish in real-world terms–referring to the Tottenville pilot. In response, Kate compares the challenge to farming, with its risks and dependencies, and mentions the implementation grant, admitting that while “$60 million is [relatively] probably not very much…it’s extremely exciting in that it helps to fund the substrate which is gone, which then can set into motion this new ecology. I won’t say it’s a kind of utopian fantasy; we have ocean acidification challenges, MSX and Dermo [disease] and other challenges.”

Image courtesy of SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE PLLC

“Here [in NYC], we just have a consciousness of that happening, and what’s exciting about the pilot that was funded–it’s a protective system that will help reduce wave action for Staten Island which was hit hard during Sandy–is the scale; the scientists that we’re working with are excited because it’s some, I don’t want to use the word tipping point, but some scale which is a test where you have a critical mass where the organisms can begin to interact..that can then push you forward.”

“Being conservationists, and being people who are observing the world around us, what we’re trying to find is the regenerative cycle back up. What is that spark–what is the series of combinations, what are the scales at which we have to work? In my mind, there are two aspects: One is the concept of increased monitoring of a scientific feedback loop that now has to come back in and be reflective of this sort of action moving forward. And the second one is…knowing that there are multiple levels of tinkering–you can’t restore nature to 1600s-era Manhattan. But you can try to reinvent the conditions under which things can take hold.”

Learn more about the project in Kate Orff’s TED talk on oystertecture: