MADE IN BROOKLYN: A Rep for Authenticity and Excellence That’s Well-Earned–and Far from New

The story behind cheese-aging facility Crown Finish Caves in Crown Heights tells of an enormous amount of risk and dedication to making something on a small scale; to doing one thing well. It also once again stirs the hive of buzz around today’s Brooklyn. Article after article raises the idea that Brooklyn’s moment as the new hot spot for excellence in food, culture and authentic, hand-crafted goods, is in some quarters regarded as trite and trendy hype with little substance to it.

For some, the underground cheese caves are just one more example: Cheese caves. How Brooklyn. Thirty feet below street level, in the lagering tunnels of a former brewery beneath the Monti Building in Crown Heights, Benton Brown and Susan Boyle spent several years renovating and creating “Brooklyn’s premier cheese-aging facility” complete with state-of-the-art humidity control and cooling systems. The couple created the 70-foot space with advice from the world’s top cheese experts; Crown Finish Caves opened in 2014. On an article in Cheese Notes, a commenter raves: “If I were a mouse, I would move to Crown Heights.”

Benton Brown of Crown Finish Caves. Image courtesy of Crown Finish Caves.

Benton Brown of Crown Finish Caves. Image courtesy of Crown Finish Caves.

The Brooklyn brand

Brooklyn Soap Company is based in…Hamburg, Germany.

Brooklyn Soap Company is based in…Hamburg, Germany.

Bedford Stuyvesant Cafe is in…Amsterdam.

Bedford Stuyvesant Cafe is in…Amsterdam.

It’s rare for a week to go by without mention of the “Brooklyn brand” in a major publication. While the borough has become a household word in a different way than it has been in recent decades (think: Saturday Night Fever), and bar owners, clothing manufacturers and food purveyors the world over are making the “little bit of Brooklyn” claim, hoping to convey the value that comes with a certain kind of authenticity, diversity and industrious spirit. And there are certainly the disingenuous: Eagle-eyed label-readers at the Brooklyn Paper called foul when home goods store West Elm–though the store’s flagship was indeed a DUMBO anchor–tried to slap the “made in Brooklyn” label on goods made in China.

Brooklyn Bowl club/music venue/bowling alley/restaurant in its London location. Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Bowl London via flickr.

Brooklyn Bowl club/music venue/bowling alley/restaurant in its London location. Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Bowl London via flickr.

Staunch Manhattanites may find it pretentious, but, according to a recent Times article, “abroad, the image of Brooklyn is one of authenticity (a Brooklyn concept if there ever was one).” A PR/branding rep of the London outpost of Williamsburg’s Brooklyn Bowl, is quoted: “With Brooklyn, there is this inclusiveness versus the exclusiveness in [Manhattan]. In New York, there is a red velvet rope and V.I.P. list. Brooklyn is about democratization.”

When put in its proper context, rather than being the product of a well-run marketing machine, the concept of Brooklyn authenticity–an insistence on excellence, of doing one thing well–and a commitment to diversity are part of a reputation that is not only well-earned but has a rich historic precedent as well.

When Brooklyn was the world

Then, and again: When Brooklyn Was the World 1920-1957; The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn: Gentrification and the Search for Authenticity in Postwar New York.

Then, and again: When Brooklyn Was the World 1920-1957; The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn: Gentrification and the Search for Authenticity in Postwar New York.

Perhaps if Brooklyn acts like the center of the universe in 2015, it’s just, you know, being Brooklyn. Noted historian Elliot Willensky’s book, When Brooklyn Was the World: 1920-1957 needs almost no further elaboration for those who know this story: To a uniquely influential generation now scattered throughout the globe, from 1920 to 1957, Brooklyn was the world.

That is likely part of the reason that today, from a marketing angle, it is an easy sell. In the same Times piece, Neil Eichner of Manhattan marketing firm Orbit 360 speaks of the mythology the borough had long before its current residents and admirers were born: “‘…especially for foreigners talking to friends and neighbors about the possibility of emigrating to America, Brooklyn is like the history of the world; everybody came in there. Then it was the home of the Dodgers. It was in its glory then. Now it’s back to that level again, and further.’”

Jenny of Better off Spread; Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Makers.

Jenny of Better off Spread; Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Makers.

The borough had been, in the last part of the previous century–perhaps ironically–the first “suburb” of Manhattan. But sometime in the early-to-mid 20th century, Brooklyn became Brooklyn. One could attribute this uniqueness of time and place to an enormous confluence of industrious middle-class immigrants of all nationalities. Artisans and tradespeople, bakers and makers and their spouses and families, all of whom took enormous pride in what they had done in the places they left behind, suddenly found themselves having to prove all over again–to New Yorkers, no less–that their pizza was indeed worth a Saturday night’s gathering or perhaps merely that their spaghetti sauce was substantial enough to nurture a generation of neighbors’ kids.

Doing one thing really well

Four generations of Gombergs are behind Brooklyn Seltzer Boys (l); Made in Brooklyn: Fox’s U-bet (r).

Four generations of Gombergs are behind Brooklyn Seltzer Boys (l); Made in Brooklyn: Fox’s U-bet (r).

Alex Gomberg of Brooklyn Seltzer Boys delivers old-school seltzer in restored original bottles to artisanal bars and restaurants who appreciate its bubbly kick–and will be selling five-dollar egg creams at Smorgasburg in DUMBO come spring. That’s so Brooklyn, you might say (perhaps with the attendant, “Go back to Ohio, hipster!”). Except there’s more to the story, though it is definitely “so Brooklyn.” It’s so Brooklyn, in fact, that it was Alex’s great-grandfather, Mo Gomberg, a Russian immigrant, who founded Gomberg Seltzer Works in Canarsie in 1953. The company supplied seltzer to a generation of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who brought their taste for it with them to America.

Ludovico Barbati, founder of L & B Spumoni Gardens, delivers pizza in 1938 (l); Dom DeMarco of Di Fara Pizza (r).

Ludovico Barbati, founder of L & B Spumoni Gardens, delivers pizza in 1938 (l); Dom DeMarco of Di Fara Pizza (r).

Still seeking excellence: Speedy Romeo founders Todd Feldman and Justin Bazdarich. Photo courtesy of Speedy Romeo; Roberta’s of Bushwick. Photo courtesy of Roberta’s.

Still seeking excellence: Speedy Romeo founders Todd Feldman and Justin Bazdarich. Photo courtesy of Speedy Romeo; Roberta’s of Bushwick. Photo courtesy of Roberta’s.

Pizza may not have been born in Brooklyn, but it certainly was perfected here. From Spumoni Gardens to Speedy Romeo, Di Fara to Roberta’s–and impressive Clinton Hill newcomer Pizza Loves Emily–pride has long been a top ingredient in Kings County pizza-making. Perpetual “best-of” Paulie Gee is a case in (Green)point. Owner Paul Giannone, who opened the restaurant in 2010 at the age of 56, is nearly obsessive about creating the perfect pie. And, like so many others, his story starts with, “I grew up in Brooklyn…”

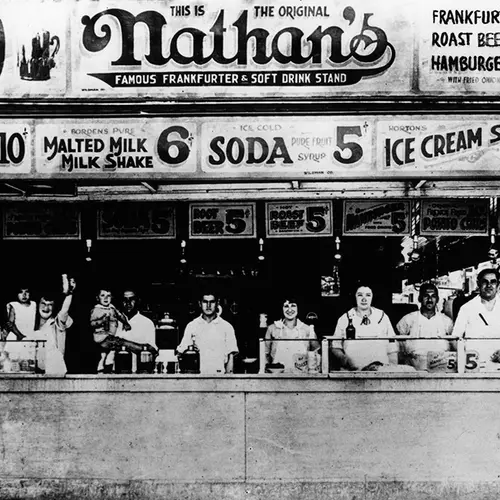

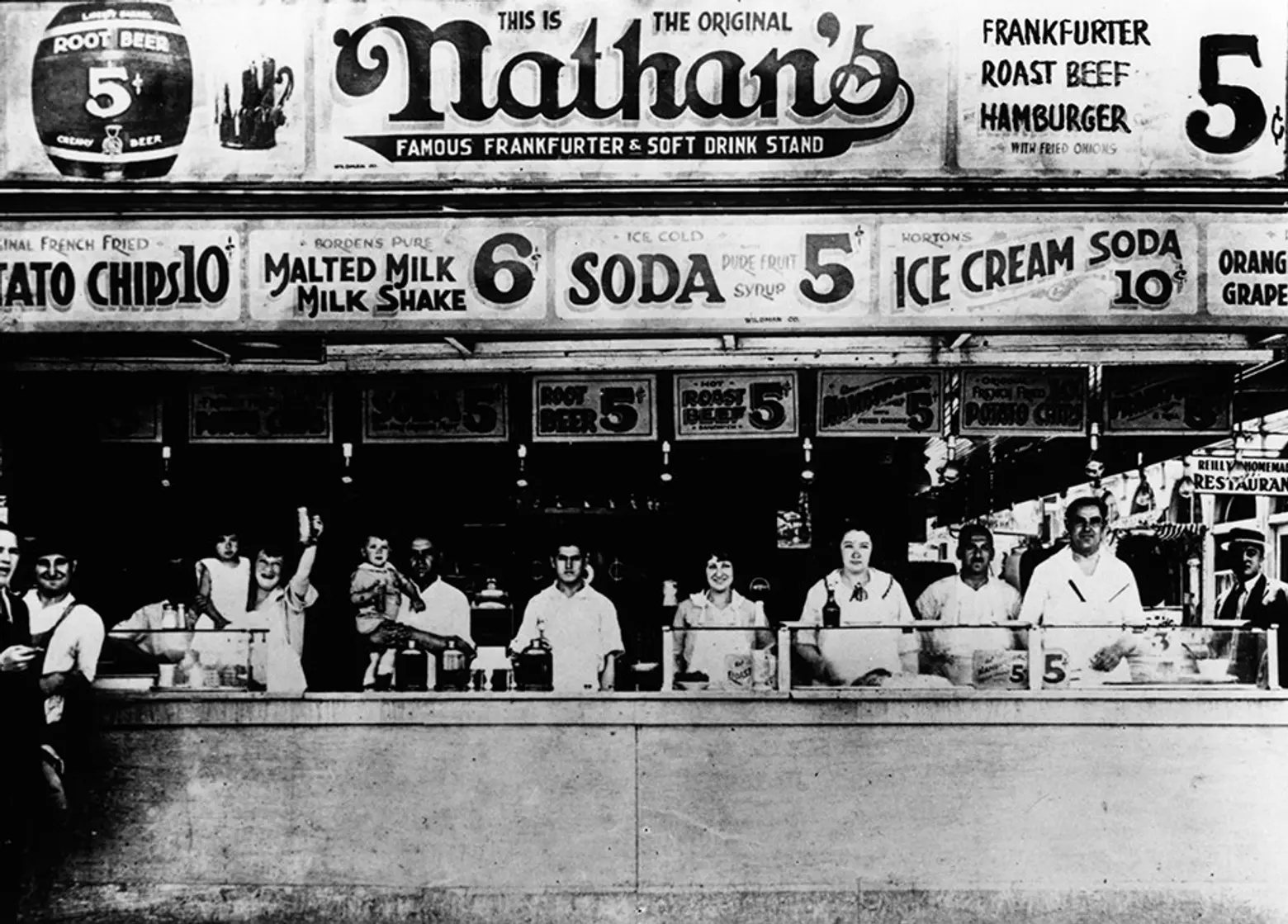

Nathan’s Famous hot dog stand in Coney Island, 1916. Photo courtesy of Nathan’s Famous.

Nathan’s Famous hot dog stand in Coney Island, 1916. Photo courtesy of Nathan’s Famous.

Americans have taken for granted the “Brooklyn brand” on our plates long before the internet put it up for debate. Nathan’s Famous hot dogs, founded in 1916 by a Polish immigrant with his wife’s recipe and a Coney Island food stand, are an enduring classic. And Fox’s U-bet chocolate syrup (historically, no proper egg cream is made without it) has been made in Brooklyn by H. Fox & Company since 1895–and they’ve been doing it for five generations.

Some still remember how you could, “…walk along 13th Avenue in Borough Park in the 1930s and 1940s and find–with no end in sight–food that today they call ‘artisanal;’ items that you would have to go to a ‘special’ bakery to find; and all varieties of vegetables straight from the farms. Caviar, barrels of pickles on the street, one was better than the next, better than most anything you can even get today. But the point is that this was an everyday thing.”

Brooklyn Brewery, launched in 1984. Photo: Brooklyn Brewery.

Brooklyn Brewery, launched in 1984. Photo: Brooklyn Brewery.

More recently, Steve Hindy—a former foreign correspondent, now in his 60s–learned home brewing in Cairo from diplomats who had learned the process while stationed in Middle Eastern countries where beer wasn’t available. In 1984, he and a partner launched Brooklyn Brewery; the company built a brewery in Williamsburg in 1996. Hindy’s decision to call the beer “Brooklyn” was originally met with some concern from investors; 1980s Brooklyn was both no longer and not yet the brand on everyone’s lips. The name turned out to be a good choice.

Lifestyle ideals and a search for authenticity

In the heyday of the American suburban boom in the 1960s and ‘70s, a small but growing number of young, well-educated New Yorkers were opting to assume ownership of dilapidated row houses in formerly genteel but now-somewhat-ragged–and sometimes downright sketchy–neighborhoods like Park Slope, Boerum Hill, Fort Greene and Clinton Hill. The authenticity these “brownstoners” sought was one of city neighborhood living–where you could have enough space to raise a family, yet still live in a community with diverse neighbors and with access to the city’s transportation, amenities and culture–that was more common abroad and before “white flight” sent the young and upwardly-mobile to the newly-minted suburbs.

Park Slope Food Co-op, founded 1973. Photo courtesy of Park Slope Food Co-op.

Park Slope Food Co-op, founded 1973. Photo courtesy of Park Slope Food Co-op.

The Park Slope Food Co op made a commitment to that diversity when it opened–in 1973, mind you–with the intention of sending a message that at a time when so many were turning their backs on urban neighborhoods, the grocery co-operative was committed to staying put, and bringing fresh, healthy and high quality foods to residents at a lower cost than regular grocery stores. That commitment still exists today, after more than 40 years, despite the fact that it is sometimes–mostly half-heartedly by those who shop there–mocked as a beacon of privilege, or a sign of the (current) times.

Maker culture

In her book, Brooklyn Makers, Jennifer Causey writes of entrepreneurs like Alison and Matt Robicelli of Robicelli’s Bakery. The Brooklyn natives explain that while growing up in the borough they found “the ‘authentic’ ethnic experiences that so many people travel the world looking for were in the houses of our neighbors.” The Brooklyn they symbolize remains filled with diverse individuals “championing a return to craftsmanship and artisanal making,” and companies like the Brooklyn-born Etsy, who give makers a platform for success.

But does today’s Brooklyn live up to the standards of its industrious past? To answer this question we head back underground to that tunnel in Crown Heights. The aforementioned proprietors slowly and painstakingly renovated–Brown also runs a sustainable design/build company called Big Sue–the industrial compound when they first occupied it in 2002, with the intention that it would someday host a new crop of artisans. Now the four-story building, drawing power from solar panels and boasting a green roof and radiant heat floors, is filled with makers of custom doors and crafters of theater sets. The Times gets it right: “Such is the New York factory in the 21st century.”

Diversity, baseball and the “Brooklyn way”

What about those lucrative exports, diversity and inclusiveness? In the famous story of baseball great Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers’ general manager, Branch Rickey, the sport’s segregated system was basically dismantled on Brooklyn soil. Rickey recruited Robinson, shepherding his move from the Negro Leagues to the all-white Majors, when America was still a deeply segregated nation. In 1945, Rickey announced that Robinson had signed a contract with the Dodgers. Within a few years, the team had hired other black players who helped turn them into one of the greatest teams in baseball history. Robinson led the “Trolley Dodgers” to six pennants; he was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962, a year before promise of a big stadium–which had not been forthcoming in NYC–enticed owner Walter O’Malley to relocate them to the opposite coast.

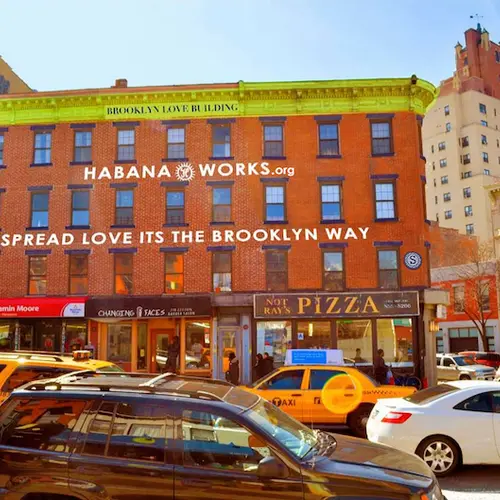

The “Brooklyn Love Building” in Fort Greene. Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Love Building.

The “Brooklyn Love Building” in Fort Greene. Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Love Building.

Only moments before Mayor Giuliani ushered in an era of “stop and frisk,” late rapper The Notorious B.I.G. offered the oft-repeated boast: “Spread love it’s the Brooklyn way.” Like the Brooklyn residents of the past, anyone who stayed put through the troubled end of the 20th century–and those who have arrived since–have had to embrace diversity. And just as in the last century, though each neighborhood had its own ethnic flavor, the whole was a melting pot. This rare diversity continues to have a profound creative influence.

The Atlantic recently wrote, “Brooklynites hate Brooklyn trend pieces. But it’s also just another way of saying it has a specific set of amenities that are appealing to a certain group—Brooklyn has become a euphemism for a kind of urbanism that millennials like.” Neighborhoods, with their deeply-rooted community infrastructure, are being “discovered” apace as the ideal model for living. Similar neighborhoods throughout the world are being compared to Brooklyn, but it took 21st century America, still shaking off the last remnants of the postwar era’s Madison Avenue-fueled world of packaged fast food mediocrity and homogenous suburbia, this long to catch up.

In today’s brave new Brooklyn, where so many intentions do indeed honor the borough’s past, there are questions to be asked, and tipping points to be noted: When does gentrification make the diversity go away? Are the things being made here now being made for everyone the way they once were? So much more than words on a building, will the “Brooklyn way,” in essence, remain in Brooklyn or be picked up and packed off, like a certain beloved baseball team of a past era, in the name of bigger, better real estate?

This mouse wants to move to Crown Heights. Photo Chris Isherwood via flickr.

This mouse wants to move to Crown Heights. Photo Chris Isherwood via flickr.