Mayor’s Affordable Housing Push Brings Tough Questions on Racial Integration

Affordability vs. racial inclusion may sound like an odd battle to be having, yet it’s one that often simmers below the surface in discussions of neighborhood change. The words “Nearly 50 years after the passage of the federal Fair Housing Act…” are, of course, no small part of the reason. And in a city known for its diversity–one that often feels more racially integrated than it is–the question of how housing policy might affect racial makeup tends to be carefully sidestepped, but the New York Times opens that worm-can in a subsection called “Race/Related.”

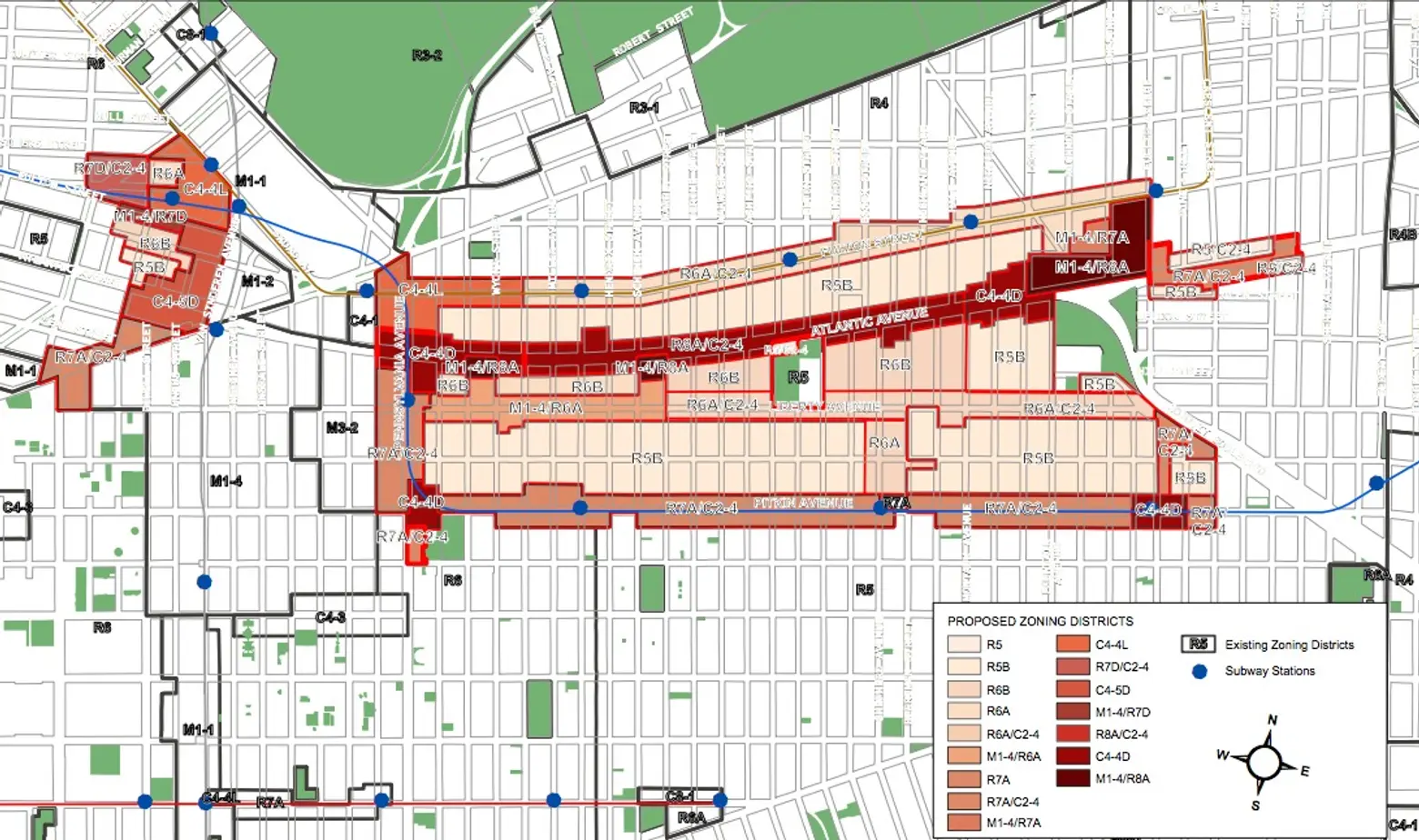

Map of proposed East New York rezoning via Department of City Planning

Housing advocates have long argued that city-subsidized apartments for poor households should be set aside in areas like East New York, a Brooklyn neighborhood targeted in the mayor’s redevelopment plan. From their perspective, the challenge lies in protecting low-income residents from being displaced as neighborhoods improve and newer market-rent residents push up housing costs.

That’s where race enters the picture: One concern is that the higher rents that come with development will bring about the “whitening” of a neighborhood that’s currently overwhelmingly black and latino. But, in the words of Ford Foundation vice president and economic opportunity and segregation specialist Xavier de Souza Briggs: “If we choose to fight for affordability only, one neighborhood at a time, that would trade away inclusion. It tends to perpetuate that segregated geography.”

Via Verde mixed-use development in the Bronx.

One method the city uses to make sure that that longtime residents can remain in areas being rezoned is the “community preferences” policy, which sets aside as much as 50 percent of new lower-cost units to applicants who live in the area. It has come to the attention of the Anti-Discrimination Center, a fair housing group who has challenged that policy in a federal lawsuit, that this strategy may perpetuate segregation: “In the case of mostly white districts, the center contended, the preferences deny black and Latino New Yorkers an equal chance for a home in better neighborhoods.”

The city’s recently-adopted mandatory inclusionary housing policy requires developers to set aside up to 30 percent of units in newly-constructed market-rate buildings for lower-rent apartments when building in neighborhoods that have been rezoned for new residential development. Developing low-income areas can increase “diversity” by bringing in higher-income residents. But it may also end up pricing out existing residents. Investing in affordable housing in more expensive areas may attract low-income residents who wouldn’t have been able to live in those areas otherwise. Critics say more affluent areas should have been included sooner; “It’s fair to say that some people are questioning why the first neighborhoods are low-income communities,” said City Councilman Brad Lander.

These conflicts have landed squarely in the lap of Mayor de Blasio, a liberal Democrat who makes noticeable effort to prove himself as an ally of both economic and racial opportunity. When asked in a meeting at the Times how much priority he placed on integration when pursuing his housing goals, Mr. de Blasio said he believed that it was, “a really important area of public policy and one where we need more and better tools.” City officials say “the key to holding displacement at bay while building mixed-income communities is to do more both to preserve existing rent-regulated units and to monitor harassment by landlords who illegally evict tenants to take advantage of rising rents in gentrifying areas.” This issue recently came to a head concerning an eviction suit involving a $62 million real estate deal in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

Discussions about integration are difficult to have without conflict. The important imperative would seem to be making sure housing policies aren’t promoting discrimination against any race, which, of course, is easier said than done. And it may come down to a choice between worst-case scenarios: Is it worse to see low-income populations displaced due to inevitable development? Or is it worse to “stack the deck” in favor of existing neighborhood residents, risking the accusation that this promotes racial segregation, because that advantage works toward maintaining the neighborhood’s racial status quo.

For a more varied perspective, this interactive feature asks residents of communities with the highest concentrations of various racial groups to share their thoughts on living in the neighborhood.

[Via New York Times]

RELATED:

- City Planning Commission Approves Controversial East New York Rezoning Plan in 12-1 Vote

- Everything You Need to Know About Affordable Housing: Applying, Getting In, and Staying Put

- Lower Income Residents of Extell’s ‘Poor Door’ Building Find Glaring Disparities

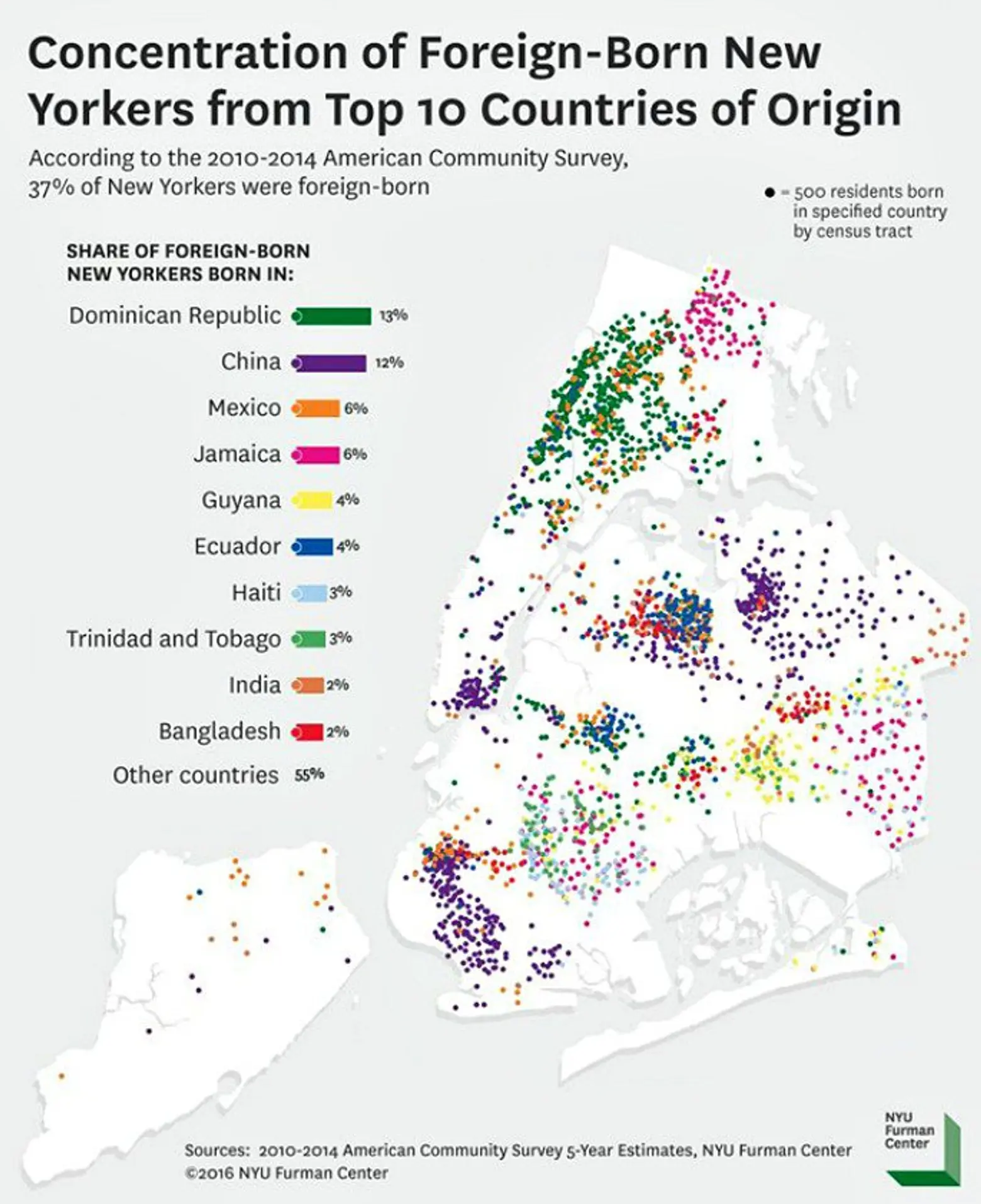

- Map Shows Where Foreign-Born New Yorkers Live