New York in the ’60s: Beach Parties and Summer Houses on Fire Island

Our series “New York in the ’60s” is a memoir by a longtime New Yorker who moved to the city after college in 1960. Each installment will take us through her journey during a pivotal decade. From $90/month apartments to working in the real “Mad Men” world, we’ll explore the city through the eyes of a spunky, driven female. In our first two installments we visited her first apartment on the Upper East Side and saw how different and similar house hunting was 50 years ago. Then, we learned about her career at an advertising magazine… looking in on the Donald Drapers of the time. Now, in our fourth installment, we accompany her to Fire Island during the warm summer months.

+++

At a press conference, a public relations woman started talking about Fire Island, which, being a Midwesterner, the girl had never heard of. A barrier island off the southern coast of Long Island, it was a fragile 30-mile-long beach dotted along its length with communities. No wider than half a mile at its widest, the island allowed no cars except emergency vehicles, and some communities had no electricity. Did the girl want to consider taking a share in a coed house there? The offer was for every other weekend in Davis Park, June 1 through Labor Day, $200 for her bed. She said yes and found herself, twice a month, in a magical place tingling with possibilities.

Getting there was no dream, however. Long Island Railroad trains ran from Penn Station towns on the south shore of Long Island, and ferries took over from there. The original and magnificent Penn Station had been slated for demolition, and the one standing in for it was a miserable, low-ceilinged, echo chamber with no seating. Oh, this is temporary, we were told. Temporary? Only in geologic terms. It’s still there and still “temporary” 53 years later.

The Casino Cafe today, via Casino Cafe

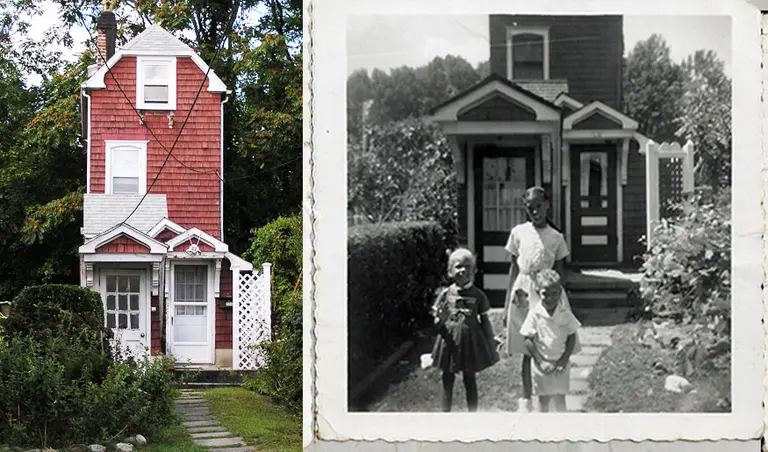

Once at the destination, however, all was forgotten. You would kick off your shoes getting off the ferry and not put them on again until Sunday on the way home. Sand was everywhere. A boardwalk connected the houses, running east and west with perpendicular spurs off to the ocean beach and to houses on the bay side. At the ferry landing was a small general store on one of those spurs, and across from it and a little east on a high dune overlooking the ocean was the Casino—not a gambling joint, as the name implies, but a restaurant, bar and dance floor. West of the ferry landing were the rental houses, the group houses, which typically had four bedrooms with two beds each, a living room, kitchen, and deck. Someone had to sweep at least once a day to keep the sand under control.

East of the ferry landing was a sparsely settled community called Ocean Ridge where many houses were owned by their inhabitants, rich bohemians by all appearances. One of them was China Machado, a well known high-fashion model recognizable from her pictures in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, who was there with her little daughter. Another denizen was an attractive man too worldly for the girl, but he seemed to like her anyway and became her flame.

There was no electricity in that community of the island, but there was gas for both cooking, lighting and for heating the water. Lighting the lamps was tricky. Gas fixtures mounted on the walls and on a couple of living room tables had mantles, which were like balls of netting that needed to be lit with a match. Mantles that came in a box provided by the landlord were sometimes defective, so it required a real knack for getting the house lit in the evening. Visions of a fire started by one of those things made lighting them even more difficult, especially in a community like Davis Park that had only a volunteer fire department, members of which would have to be summoned from whatever they were doing to gear up and get there before the house was a cinder.

On Saturday evenings, one of the group houses would have a cocktail party starting around six. Every weekend it was a different house—”Who’s doing the six-ish this weekend?” was a cry heard every Saturday morning. Everyone was invited and scores of people would arrive with their drinks and stand around talking, nibbling and drinking until it was time to get something to eat and then go to the Casino and “twist the night away,” to the tunes of Chubby Checker.

The beach where everyone lounged and played volleyball eroded a little every year, the sands shifting with the storms. Houses overlooking the ocean were—and are—in jeopardy, like the barrier island itself. Most of the people there in the summer were in New York in the winter: a community that numbered 4,500 households from June through September dwindled to 200 during the rest of the year. That hard core claimed to love the solitariness and the wild nature of Fire Island in the winter despite its inconveniences. Procuring food was one of them, but the weather was another. Storms were magnificent acts of nature seen up close and frightening, as acts of nature are. People there during the winter could hardly protect every house, often not even their own.

By 1964 beach erosion had become a serious enough problem that the United States National Park Service proclaimed Fire Island a National Seashore and restricted further building on it. The designation didn’t make much difference to life on the island—it wasn’t intended to—and to this day hundreds of people enjoy a barefoot summer there, fishing in the ocean and bay, swimming, plucking duneberries for jam, and dropping in on each other unannounced. If storms have damaged Fire Island, it has almost always recovered. Climate change and rising sea levels could change that. The National Park Service claims ownership of the island for 50 years, but the island is hundreds or thousands of years old.

+++

RELATED: