New York in the ’60s: The Assassination of JFK and the Plight of the Tobacco Industry

“New York in the ’60s” is a memoir series by a longtime New Yorker who moved to the city after college in 1960. From $90/month apartments to working in the real “Mad Men” world, each installment explores the city through the eyes of a spunky, driven female. In the first two pieces we saw how different and similar house hunting was 50 years ago and visited her first apartment on the Upper East Side. Then, we learned about her career at an advertising magazine and accompanied her to Fire Island during the warm summer months. Our character next decided to make the big move downtown, but it wasn’t quite what she expected. Now she’ll take us through how the media world reacted to JFK’s assassination, as well as the rise and fall of the tobacco industry.

One day in November 1963 when the girl returned to the office after lunch, she found her colleagues gathered in small knots murmuring. One of them told her President John F. Kennedy had been shot and killed in Dallas. Not possible. It wasn’t true, it couldn’t be. But as we now know, it was. No one knew what would happen next, or what to do. It took a while for staff people to pull themselves together and eventually figure out how the magazine should respond to this disaster. It couldn’t be ignored. However, for a bi-weekly with a publication date six days later, and a special-interest magazine at that, coverage could only be limited. In the end, they decided to describe how the advertising media responded, a narrow window on the event but the one the editors felt was appropriate.

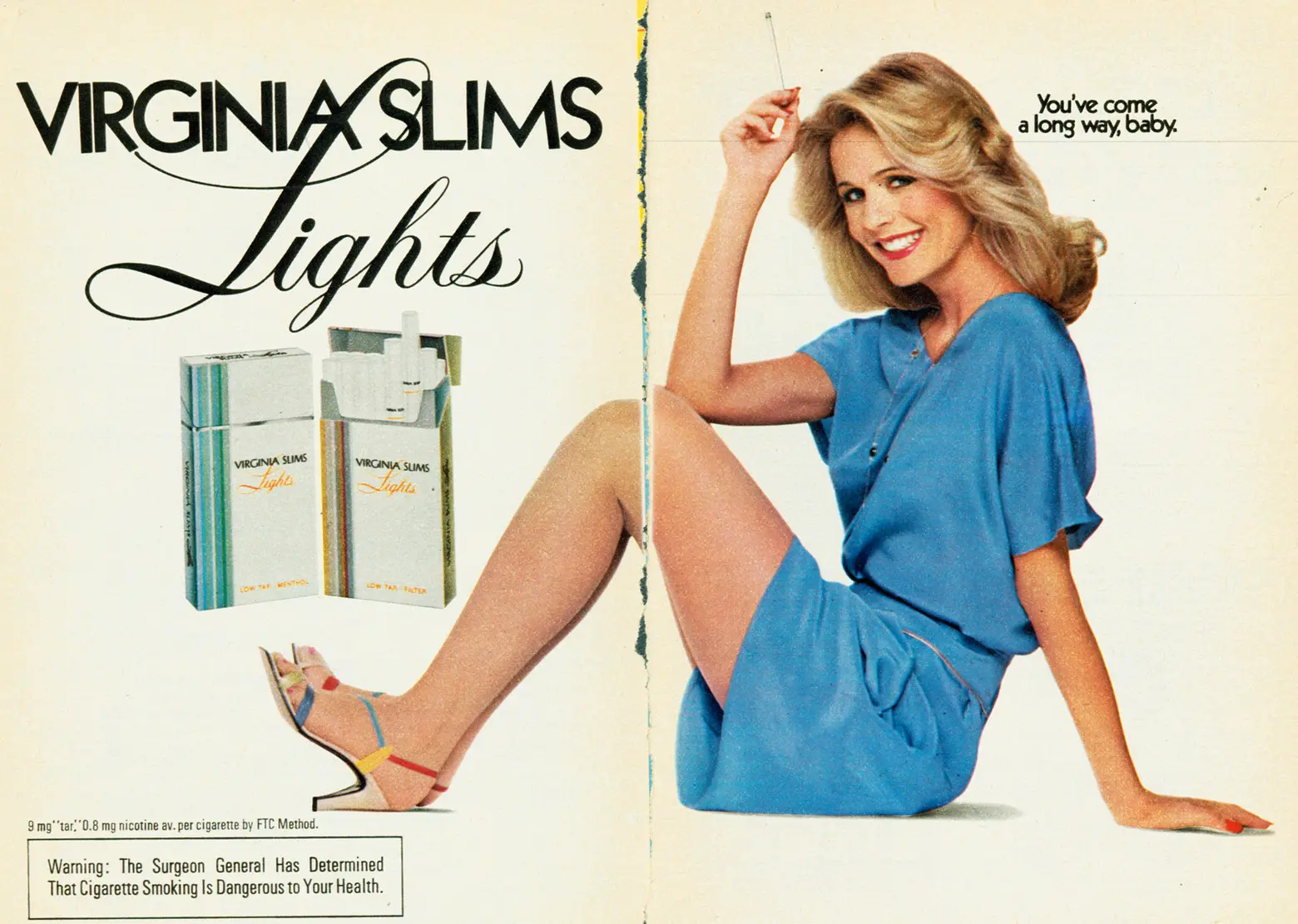

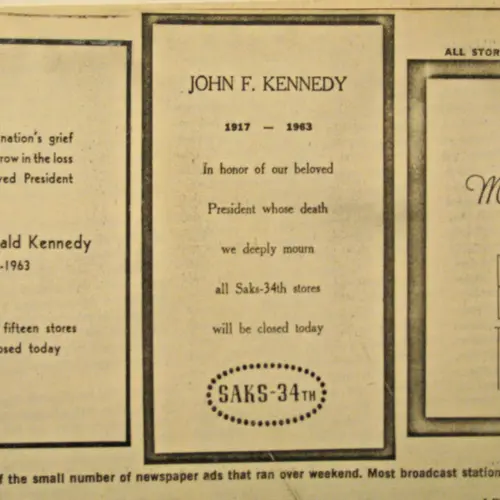

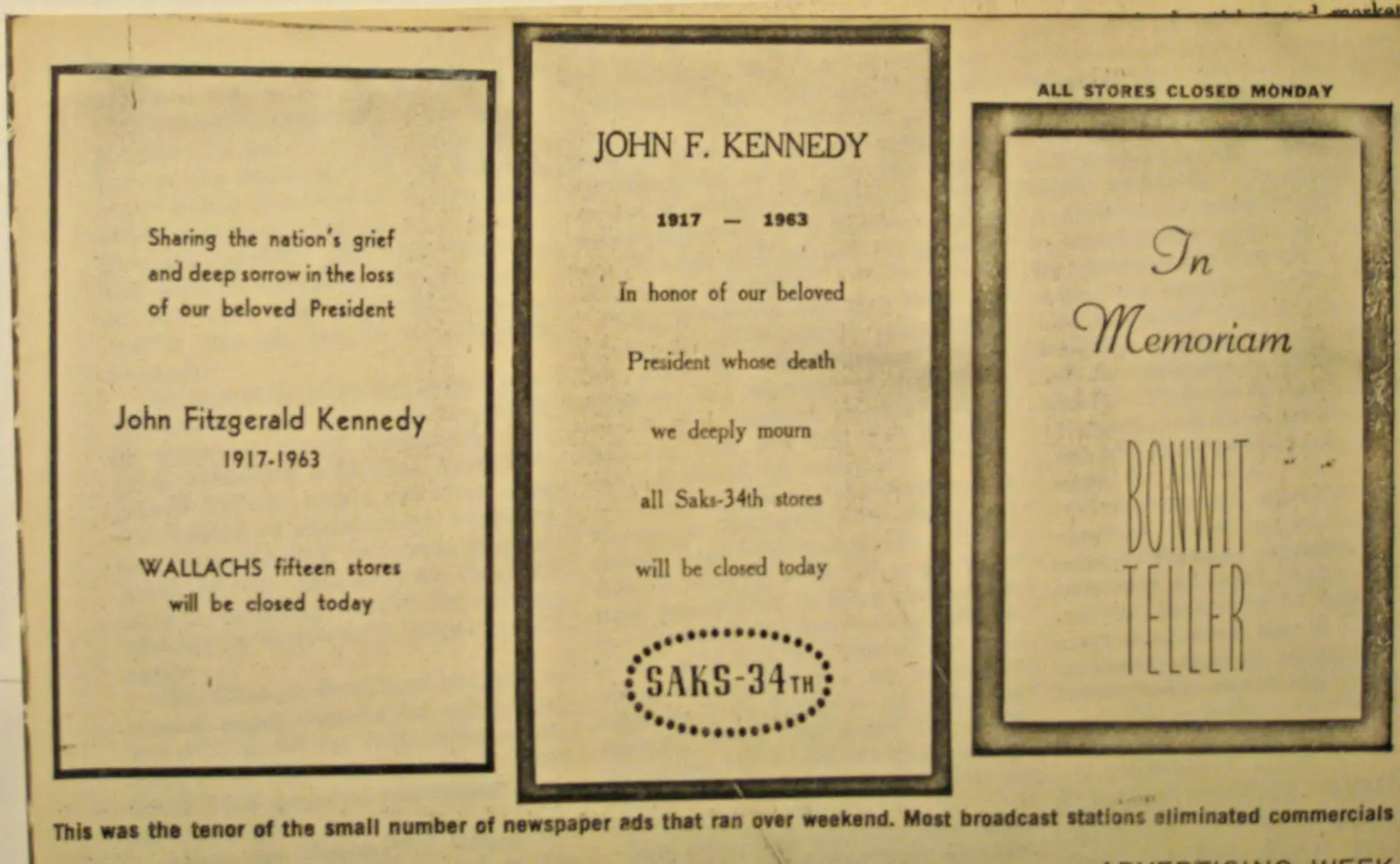

A feature in Printers’ Ink of special ads that ran in the newspaper in the wake of JFK’s assassination

Broadcast media dropped advertising in favor of news, music and filmed tributes; and print media—newspapers, principally—ran black-bordered ads for its regular retail advertisers. Printers’ Ink‘s article included this: “When the regular schedules were resumed, network TV alone had thrown a total of some 200 hours into such coverage, of which about 120 hours—a rough estimate—normally would have been commercial time.” It went further, detailing voluntary censorship. “All prefilmed or taped programs, and there are hundreds, now have to be reviewed by the standards department to snip out any inappropriate themes or references. . . This week’s scheduled episode of CBS’ ‘Route 66,’ to give one example, was entitled ‘I Have to Kill a King,’ and dealt with the theme of assassination.” And this: “Across the country, the outdoor-advertising business participated in the mourning by putting up 3,000 posters, black-bordered and bearing the date, November 22, 1963.” It was an outpouring of institutional grief hardly anybody had ever seen, and not for nearly 40 years—until September 11, 2001—would the country be so shaken.

Kennedy will be remembered for many things, but one of the measures undertaken during his presidency had far-reaching consequences that affected social and personal life in small but important ways. Luther Terry was appointed Surgeon General of the United States. In 1962 with a special panel he began a study that was released in January 1964 relating cigarette smoking to cancer. Studies had gone on before this date, but the Surgeon General’s report made it official. The tobacco industry formed the Tobacco Institute and hired heavy guns from the advertising industry—Rosser Reeves, late of the Ted Bates advertising agency, for one—to come up with ways to counter the bad rap. Cigarette advertising had been a lucrative source of revenue for magazines and television, but soon it would be banned. Phrases like “L.S.M.F.T.—Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco” would become a thing of the past. “I’d Walk a Mile for a Camel,” ditto.

At the time, to walk down the street with a cigarette was something only prostitutes did, or men; it was considered coarse and déclassé in the extreme, whether you were just holding it or, heaven forbid, inhaling. It was so permissible to smoke indoors—even in hospitals—that when the girl entered the subway system for the first time with her sister in 1960, she was surprised to be told just as she was about to light up that smoking was not allowed in the subway. You could certainly smoke in the King Cole Room at the St. Regis Hotel, where the girl was taken dining and dancing, or in bus stations, where she brushed her cigarette against a waiting passenger and scorched his coat. And you could certainly smoke at private parties. When she gave one, she was appalled to see one of the guests drop his cigarette onto her white flokati rug and grind it out with his shoe.

Ultimately tobacco lost its place as a cultural icon. No more children would grow up seeing their fathers tap a non-filtered cigarette on their thumb nails to settle the tobacco before lighting up. Zippo lighters would become collectors’ items. Restaurants would stop supplying books of matches to patrons. All these things took years, of course, and it also took years for many people to quit smoking. The girl herself tried six or seven times before she finally succeeded in the late 1980s. Some tobacco companies came out with “lite” cigarettes—basically with more efficient filters (some said it enabled them to use inferior tobacco) or thinner, like Virginia Slims. Just about every cigarette manufacturer produced a mentholated version, which did little except create an illusion of a cooler smoke. Cigarettes cost about 50 cents a pack, so taxes were levied with increasing weight. And the surgeon general’s report was bannered across every pack. More people smoked in the ’60s than didn’t, just as today more people don’t smoke than do–or so it seems. It has taken 50 years to make that transition, but that it happened at all, especially in a democracy, is remarkable.

+++

RELATED:

- New York in the ’60s: Apartment Hunting, Job Searching, and Starting Out in the Big City

- New York in the ’60s: Domestic Yearnings, Yorkville Hangouts and Bartenders

- New York in the ’60s: Being a Woman in Advertising During the ‘Mad Men’ Days

- New York in the ’60s: Beach Parties and Summer Houses on Fire Island

- New York in the ’60s: Moving Downtown Comes With Colorful Characters and Sex Parties

- New York in the ’60s: When Chelsea Apartments Were $111 a Month