New Yorker Spotlight: William Helmreich Went on the Ultimate 6,000-Mile Walking Tour of NYC

New Yorkers are known for spending their free time taking leisurely strolls through the city’s numerous neighborhoods. They even use their feet as a means to learn by going on weekend walking tours to discover the history, the mystery, as well as the evolution of their favorite places—and there are certainly plenty of tours out there to serve all sorts of curiosities. But when William Helmreich decided he wanted to learn more about New York on foot, he took walking tours to another level. In fact, he decided to walk the entire city.

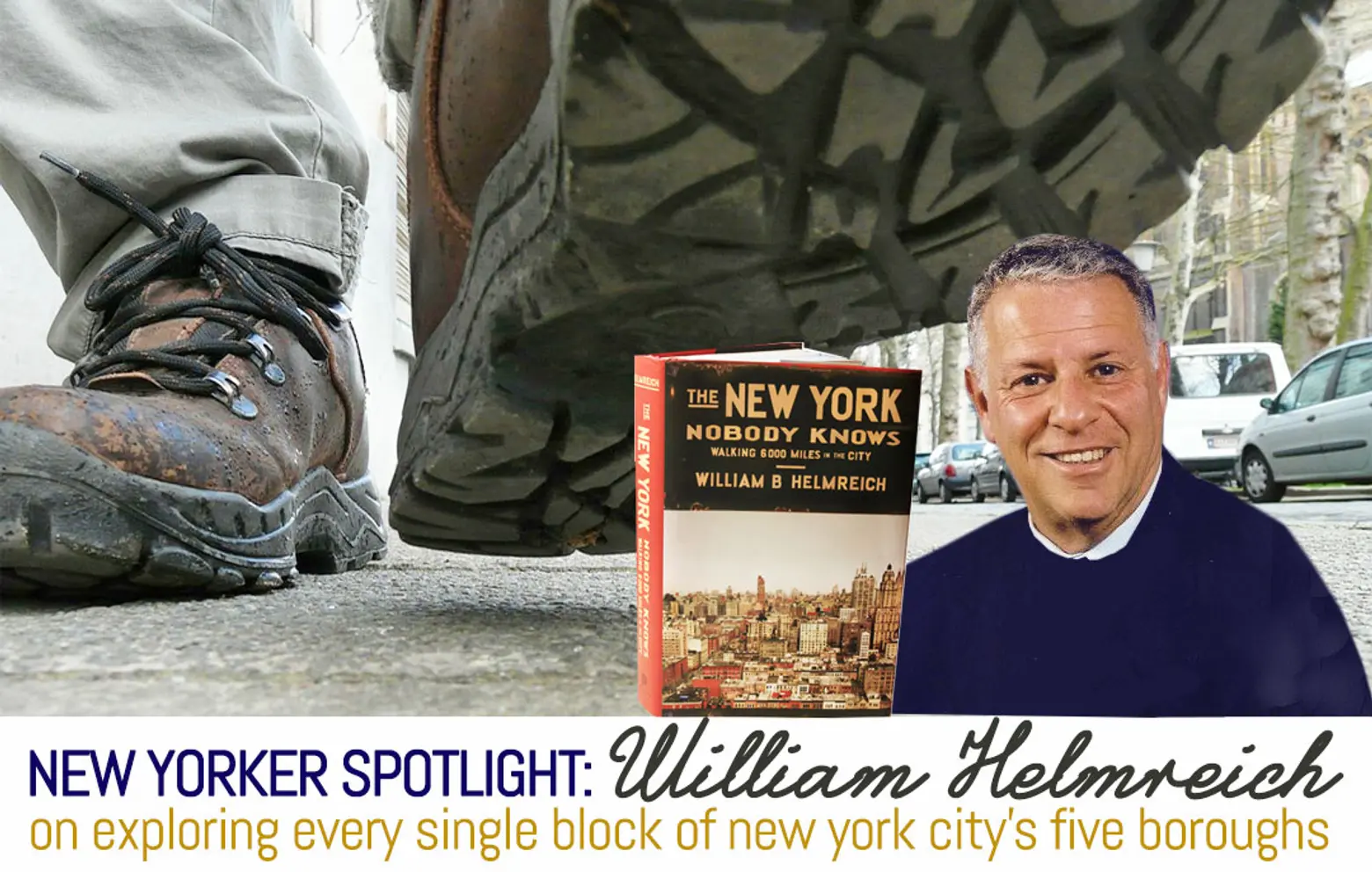

William is a sociology professor at The City College of New York and also teaches at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Over the course of four years, he has walked just about every block in New York City. It was an adventure William was primed for as a lifelong New Yorker who possesses a research interest in urban studies; his background allowed him to be at ease while speaking with city residents in the five boroughs, and he had the eagerness necessary to uncover hidden gems in the lesser known nooks and crannies of our metropolis. The culmination of William’s journey is his book, “The New York Nobody Knows: Walking 6,000 Miles in New York City,” which was published in 2013 and released last month in paperback.

We recently spoke with William about his long walk, and to find out what it taught him about New York.

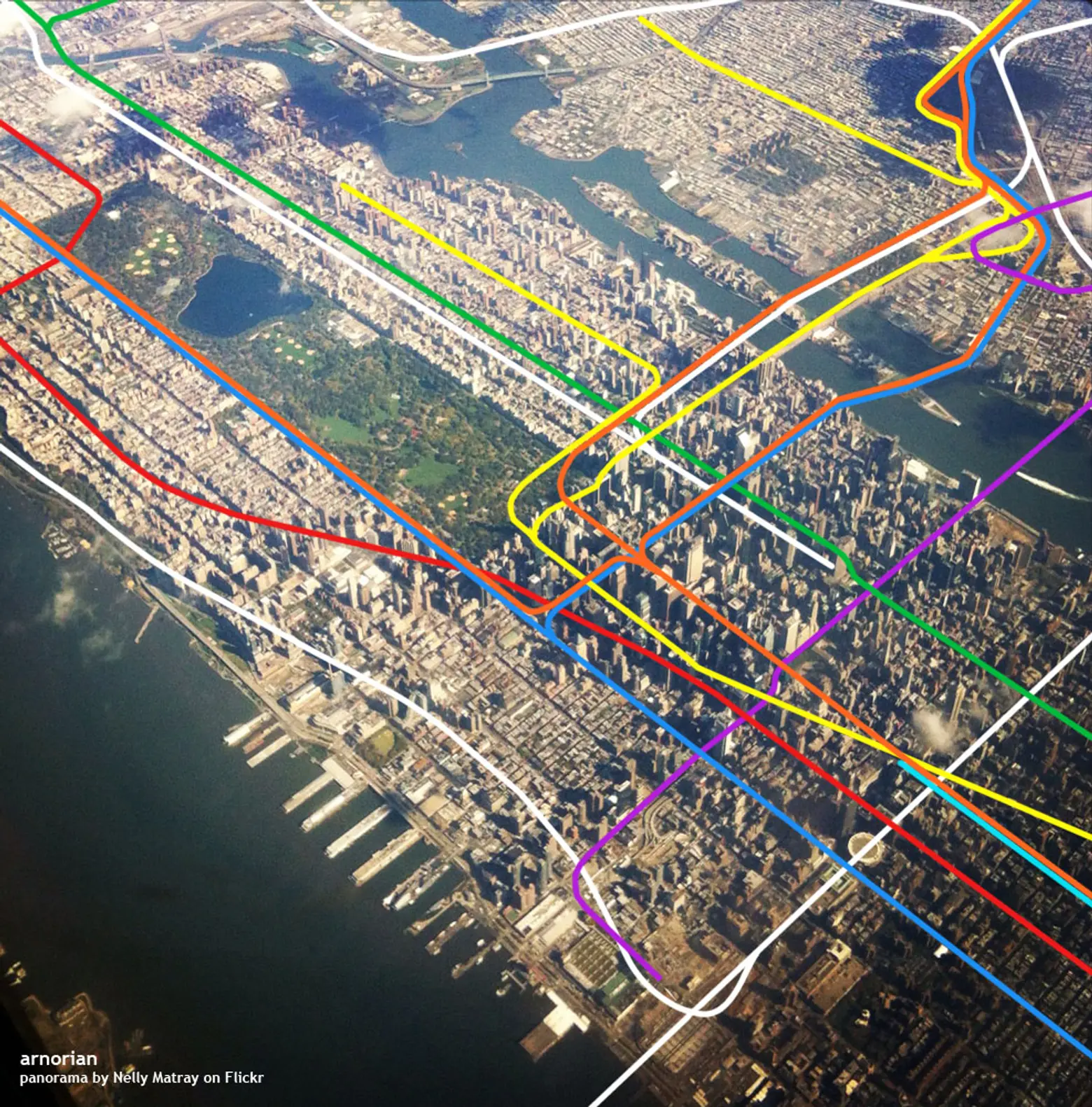

Image: Subway overlay by Anorian

Image: Subway overlay by Anorian

What inspired you to walk the entirety of New York City?

Well, it happened in a sense that when I was a kid—and that’s where its origins lie—growing up in Manhattan on the Upper West Side, my father devised a game to keep me interested called “Last Stop.” Every weekend when he had time from about the ages of 7 to 12, we would take the subway to the last stop and walk around the neighborhood—and New York then had 212 miles of subway lines. When we ran out of the last stops, we went to the second to last stop, then the third to last stop. I would go to neighborhoods in Brooklyn, neighborhoods in Queens, and in that way my love for the city was kindled.

Later on I began teaching at City College, I gave a master’s course there and also a PhD course at CUNY Graduate Center on New York City. Very often that involved taking the students on walks through neighborhoods. After I had been doing this for about forty years, my chairman said, “Why don’t you just write a book about New York, since you know the city so well and you’ve done it so long.”

How did a book lead to a walk?

Now of course in an academic course you have a bibliography and I knew the literature pretty well. I soon realized there was no book about New York City by a sociologist. Maybe a neighborhood book, a book about the Upper West Side, a book about Canarsie, and things like that, but no sociologist had even done a book on one borough, and in fact there weren’t any books of that sort except the traditional guidebooks that tell you where the Empire State Building is. The hidden aspects of New York were very, very understudied and unknown.

I was asked to write a proposal by Princeton University Press. They said, “Great. How would you do it?” I said, “Well, I’ll pick 20 representative streets of New York City, maybe Broadway, maybe 125th Street.” But I soon realized that there was no reason in a city with 121,000 blocks, all of which I was eventually to walk, that would justify my picking only 20 streets. How can you decide on any 20 streets to represent an entire city of 8.3 million people?

So I reluctantly concluded that I would have to walk the entire city if I was to understand it. And that’s how the idea was born. Now, if I had realized how hard this was at the beginning of it, I might never have undertaken it. But just like you climb a mountain, you walk a city one block at a time.

How many miles did you walk?

6,048 miles over four years. 30 miles a week. 120 miles a month. 1,500 miles a year. Four times 15 is 6,000 and you’re pretty much there. That’s like walking to California and back and then to St. Louis. According to the Sanitation Department, the city is about 6,163 miles. So I left out about 115 miles. After all, you do need to leave something for next time.

Was this a physically arduous journey?

If you want to walk a city of this complexity, you must realize that you got to be walking all the time and there is no such thing as bad weather. In fact, that’s what the Scandinavians say. There’s only bad clothing. You just dress warm. If you wait for only nice weather, you’ll never get it done. This is not San Diego. You’ve got to be committed. I’ve walked in snowstorms. I’ve walked in 90 degree heat. I just do it because you can’t get it down otherwise. As a matter of fact, to walk in general you must be extremely disciplined. There is no such thing as checking your email five times a day if you want to get something like this done because it takes an hour, sometimes an hour and a half, to get where you want to go. Then there is four, five, six hours of walking. Then you got to come home, write it up, you’ve got to make it into a narrative for the book, all the footnotes have to be right, all the references have to be right.

How many pairs of sneakers did you go through?

About nine.

How did you decide where to start?

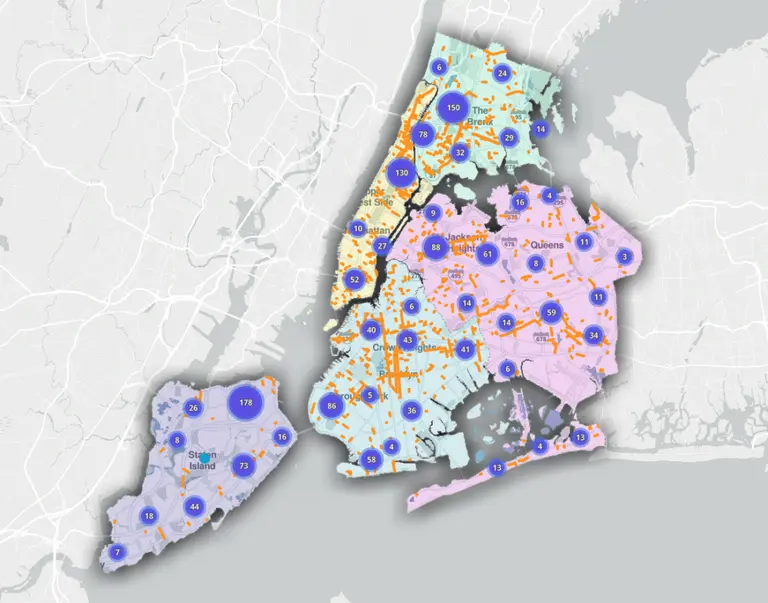

You have to start somewhere, but it didn’t really matter where I started since I was going to do everything anyway. I happened to start in North Flushing in Queens and I ended in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. I had maps of every neighborhood. Every time I came home I recorded the distance with my pedometer and second, I crossed off the streets I had walked.

How did the people you encountered along the way respond to your project?

I didn’t always tell them. But when I told them, they liked it. They thought it was a cool idea. One of the enduring truths and interesting things about New York City is that people are a lot friendlier than you think, provided you don’t have an attitude and you smile. Pretty much no matter what neighborhood I walked in, East New York, Brooklyn Heights, everyone was very friendly.

My way of doing an interview is not, “Excuse me, I’m writing a book about New York.” I say, “Hey, how you doing?” I start talking to them and before they know it, they’re in the interview. I saw a man walking in Bushwick with four pitbulls and a boa constrictor wrapped around his neck on a Sunday morning and I just fell into step with him.

Were you ever surprised by what you uncovered?

I was surprised by how well the immigrants in the city get along with each other. I think the reason why is because here when everybody is new, nobody is new.

Did you find any hidden architectural and design gems?

I would say that I couldn’t really recount them all. In my book you will find them all in a chapter called “Spaces,” where I talk about all the spaces of New York. The spaces can be books stacked up in a restaurant for no particular reason until you go in and ask why. But they can also be very interesting buildings—and I discuss many buildings. Not the ordinary tourist buildings that you normally think of. For example, on Bedford Avenue at Beverly Road there’s the old Sears Roebuck Building, the first building Sears Roebuck built. It’s an architectural delight. If you go to Bushwick, you’ll find all sorts of graffiti murals, world class murals, beautiful viewing sites. It really, really depends on the neighborhood. If you go to Washington Heights for example, you’ll find all sorts of buildings and all sorts of streets. There’s no part of the city that doesn’t have interesting things to see.

Photo credit: Cameron Baylock

Photo credit: Cameron Baylock

Having seen the entire city, can you now say one neighborhood or street is your absolute favorite?

Well, it’s a little hard to say because I really liked so many of them. But if I had to pick neighborhoods, I really love Bay Ridge because it has great diversity in terms of architectural styles, in terms of the apartment buildings, in terms of the beautiful homes along Shore Road. I would say portions of Greenpoint are very interesting because they’re very quaint and they have the old style houses. This is also true of Ridgewood along Mrytle Avenue, where you have these beautiful yellow brick houses that were built in the late 19th century, and the bricks came from the German owned Kreischer Brick Works. There was a village in Staten Island called Kreischerville. Forest Hills Gardens is architecturally known and a delight to see. The brownstones in the ’70s and ’80s in Manhattan are obviously very beautiful, as is the West Village. Brooklyn Heights and Cobble Hill are really, really nice.

They all have different attractions and appeal. Some the housing. Some the parks. In Staten Island for example, there is a Chinese Scholar’s Garden in Snug Harbor.

What does one learn from taking a walk like this?

That the city is the world’s greatest outdoor museum. It’s just the city that keeps giving and giving and it’s always changing. Another thing you learn is there will be a mural there and six months later, it won’t be there. There will be a building there and six months later it won’t be there. There will be people there and then they won’t be there. A restaurant won’t be there. Everything is replaced by something else. So the city is like this unfolding tableau that keeps on changing its identity. It’s sort of like you look at a kaleidoscope and each time you look, it’s different.

The Twin towers in 1978

The Twin towers in 1978

You learn also that 9/11 is seared into the consciousness of people in a way that they will never forget. Especially when you go to the outer boroughs, there’s always a street named after a fireman or policeman who died. But there’s another reason why for 9/11 this is so. First of all, we were never invaded except in Pearl Harbor. It’s not like Europe. It’s not like Japan, which had Hiroshima. Another thing, this was a huge because everyone saw it. New York has 71 miles of coastal line and people from Belle Harbor to Soundview in the Bronx to Brooklyn, saw this tragedy. This huge gaping hole had appeared in the skyline that they grew up with and looked at for decades.

I also found that gentrification is an enduring feature, but that it’s a complex phenomenon. People want the city to look nicer, they want it to be safer, but they also want affordable housing for people. There’s always this push and pull.

Do you often reference this experience when teaching?

I have classes of 90 or 100 students. I say to them, “Hey guys, you tell me what neighborhood you live in and I’ll tell you a story about it. If you live in New York City, I’ve walked by your house. I may not have know it, but I walked by your house.” They love hearing about New York. It’s their city.

Did walking all of New York change you?

Not much. I was always pretty outgoing. If you’re going to do these hundreds of interviews with people, you have to be able to walk up to total strangers and engage them in conversation.

After accomplishing a feat like this, what does one do next?

Princeton gave me a contract to write five more books about New York. I am doing five books: “The Brooklyn Nobody Knows,” “The Manhattan Nobody Knows,” “The Queens Nobody Knows,” “The Bronx . . . Staten Island.” I finished researching and writing the book on Brooklyn. I walked Brooklyn again.

+++

You can order a copy of “The New York Nobody Knows” here.

[This interview has been edited]

MORE SPOTLIGHTS TO CHECK OUT: