The Bedrock Myth: The Evolution of the NYC Skyline Was More About Dollars Than Rocks

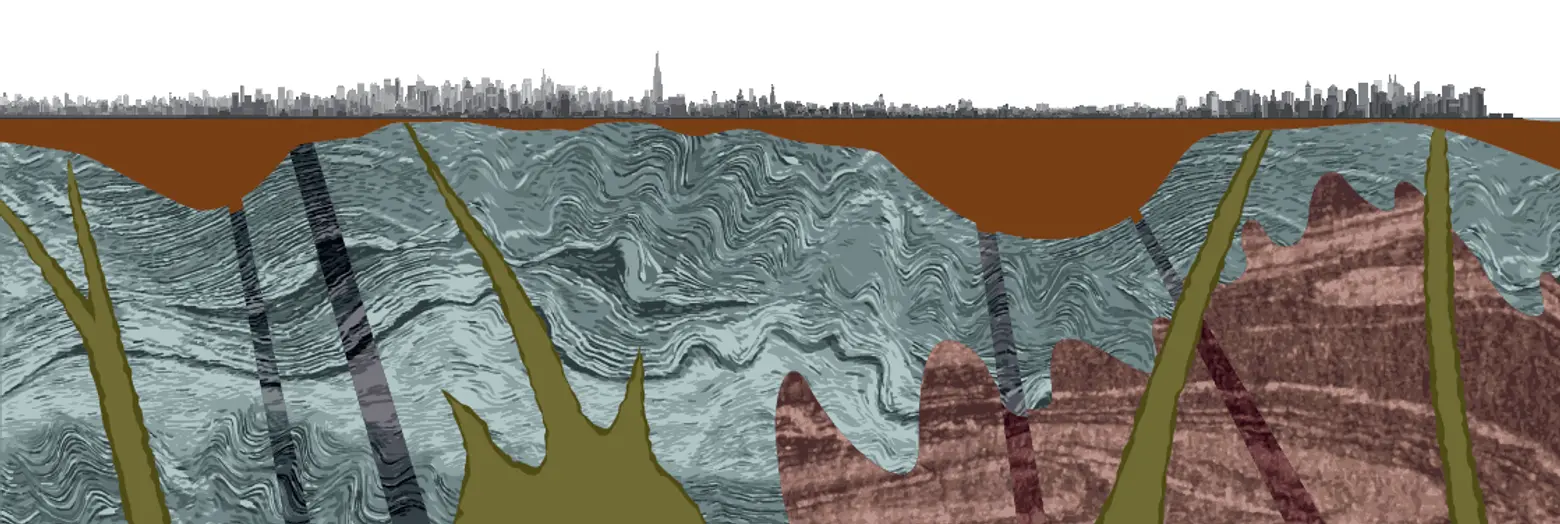

Manhattan, and the bedrock beneath it, via imgur

The reason so many skyscrapers are clustered Downtown and in Midtown isn’t so much because of geological feasibility as because everybody else was doing it.

It was long assumed that the depth of our venerable Manhattan Schist bedrock, well-suited for the construction of tall buildings, was the determinant in where the city’s towers rose. Though the bedrock outcroppings are indeed at their deepest and closest to the surface in the areas where many of the city’s tallest buildings are clustered, it’s more likely to be coincidence than cause and effect. The real reason there’s a big doughnut hole in the spiky man-made terrain between FiDi and Midtown has more to do with the way the city’s dual business districts developed from a sociological and economic perspective between 1890 and 1915.

The bedrock, if you will, of the bedrock theory is geologist Christopher J. Schuberth’s famous findings in the 1968 “The Geology of New York City and Environs,” which supported a correlation between bedrock and big buildings. While the foundation hasn’t crumbled, the cause-and-effect factor has since been debunked, as “skyscraper economist” Jason Barr told the Observer in an article on the subject. Barr studies things like the economic determinants of how high Manhattan skyscrapers are and, fascinatingly, whether we can foretell calamity by looking at the historic precedent of building height (much like the theories tying women’s hemlines to times of feast and famine). According to Barr, “These things tend to get built, and then people go looking for the crisis.”

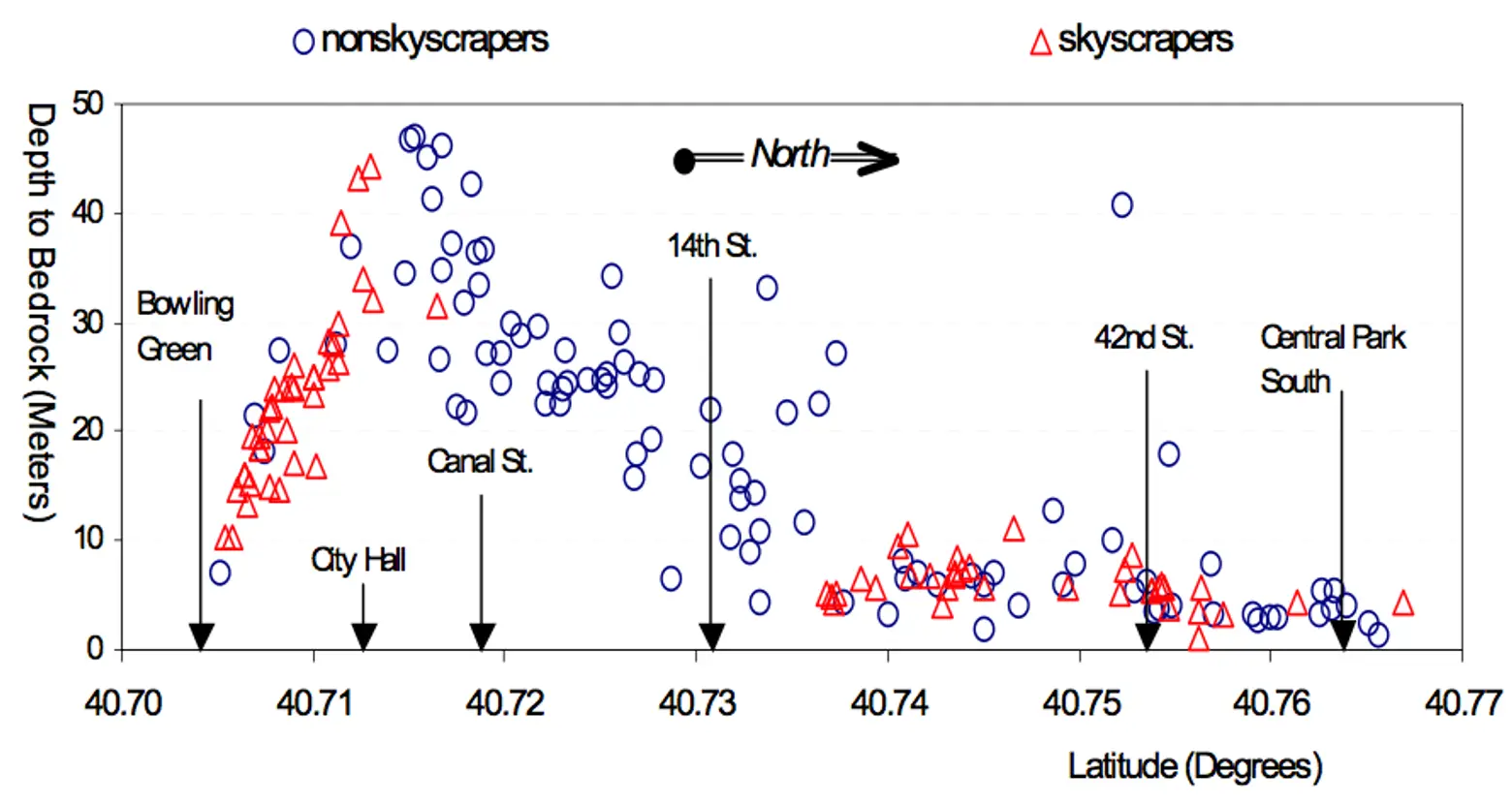

Graph: Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890–1915, JASON BARR, TROY TASSIER and ROSSEN TRENDAFILOV (2011); via NYO.

Graph: Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890–1915, JASON BARR, TROY TASSIER and ROSSEN TRENDAFILOV (2011); via NYO.

Just to be clear, Manhattan does have the good fortune of being built on nice solid rock, and plenty of it. But it turns out that what lies beneath hasn’t really limited what has sprung forth. Barr, along with two colleagues from Fordham, published a study (PDF) in The Journal of Economic History in 2011 debunking what he calls the Manhattan bedrock myth. Barr and his colleagues show that, for the time between 1890 and 1915 when the city’s densest business districts grew, there was no correlation between the depth of bedrock and the likelihood of building to 18 stories tall or higher. In fact, many of the city’s historic skyscrapers sit in areas where the bedrock is in fact at its most shallow.

Today, the depth of bedrock isn’t even much of an issue–the technology exists to build up almost anywhere. As the saying goes, the sky–and the depth of developers’ pockets–not the ground below, is the limit.

RELATED:

- Graphs Show How Skyscrapers Relate to Their Cities–and Whether We Need More of Them

- The Wild and Dark History of the Empire State Building

- Loophole Allows Developers to Build ‘Skyscrapers on Stilts’ to Give Residents Ocean Views

- New Yorker Spotlight: Paleontologist Mark Norell Spends His Days with Dinosaurs at the Museum of Natural History