The Most Important Towers Shaping Central Park’s South Corridor, AKA Billionaires’ Row

Carter Uncut brings New York City’s development news under the critical eye of resident architecture critic Carter B. Horsley. This week Carter kicks off a nine-part series, “Skyline Wars,” which will examine the explosive and unprecedented supertall phenomenon that is transforming the city’s silhouette. To start, Carter zooms in on the biggest developments shaping the southern corridor of Central Park.

They did not come from outer space when they landed on our front yard while the NIMBY folk and the city’s planners and preservationists weren’t looking. Some are scrawny. Some are dressed like respectable oldsters. They’re the supertalls and they’re coming to a site near you.

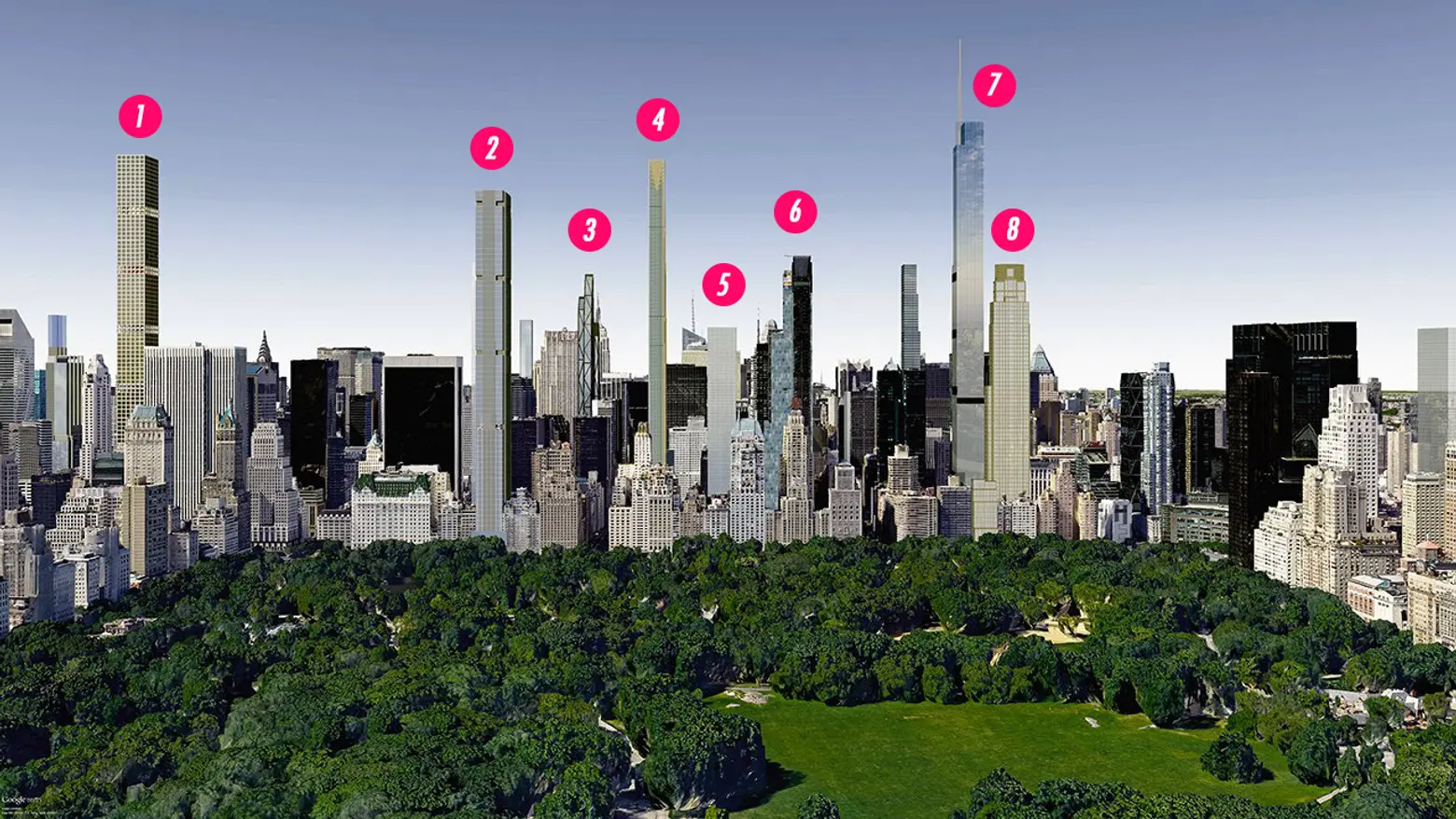

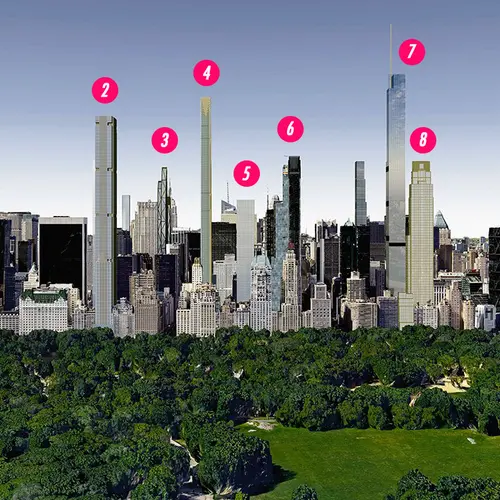

IN PERSPECTIVE:

This Google Earth rendering above by CityRealty.com, shows some of the supertalls around the south end of Central Park. From left to right:

(1) 432 Park Avenue at 57th Street, nearing completion, designed by Rafael Vinoly for Harry Macklowe;

(2) Witkoff/Macklowe redevelopment of Park Lane Hotel at 36 Central Park South;

(3) 53 West 53rd Street tower by Jean Nouvel for Hines, now in foundation work;

(4) 111 West 57th Street by JDS and Property Management Group by SHoP Architects, now in foundation work;

(5) Possible Calvary Baptist Church/Salisbury Hotel redevelopment at 123 West 57th, shown in gray, by Extell Development;

(6) One57 for Extell Development by Christian de Portzamparc, recently opened;

(7) Central Park Tower at 217 West 57th Street by Adrian Smith Gordon Gill for Extell Development, now in foundation work; and

(8) 220 Central Park South for Vornado by Robert A. M. Stern, now in foundation work.

Not shown are (9) 520 Park Avenue by Robert A. M. Stern, a mid-block building on 60th Street, now in foundation work, and (10) 29 West 57th Street in planning by Vornado and the LeFrak Organization.

At the right are the two towers of the Time Warner Center at Columbus Circle that were completed in 2003.

When we look at the future New York skyline, we tend to compare its skyscrapers within the context of other buildings within city limits. But before there was even One57 there was the free-standing Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates. The tower opened in 2010 and was designed by Adrian Smith and Gordon Gill when they were with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). At 2,722 feet high it is the world’s tallest building, and dwarfs New York’s newest crop of supertalls—which to date, none are yet planned to even touch 2,000 feet (the tallest in the pipeline, a reported 1,550 feet).

In recent decades, New York City’s dominance as the world’s great skyscraper haven has been greatly challenged and diminished. However, the city’s wave of residential supertalls is growing substantive and there is no doubt that they are about to soon dramatically transform our perception and appreciation of our city.

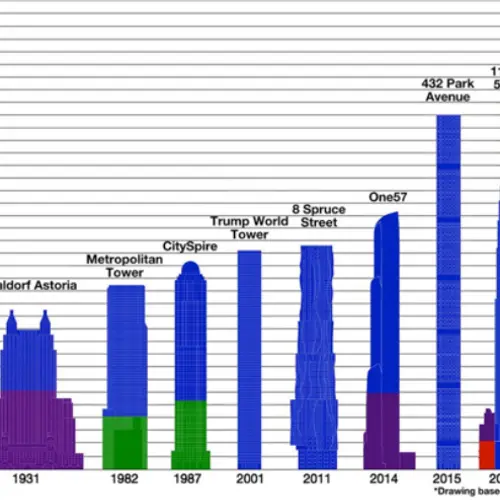

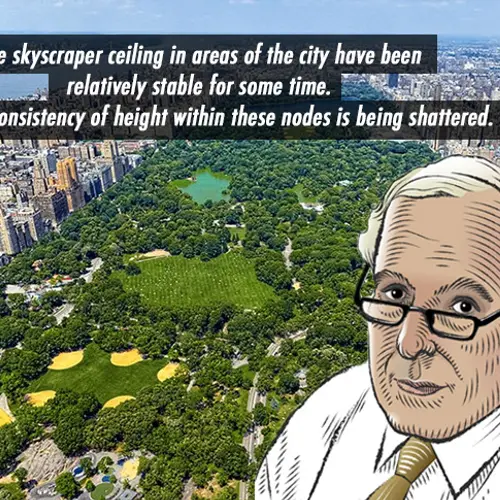

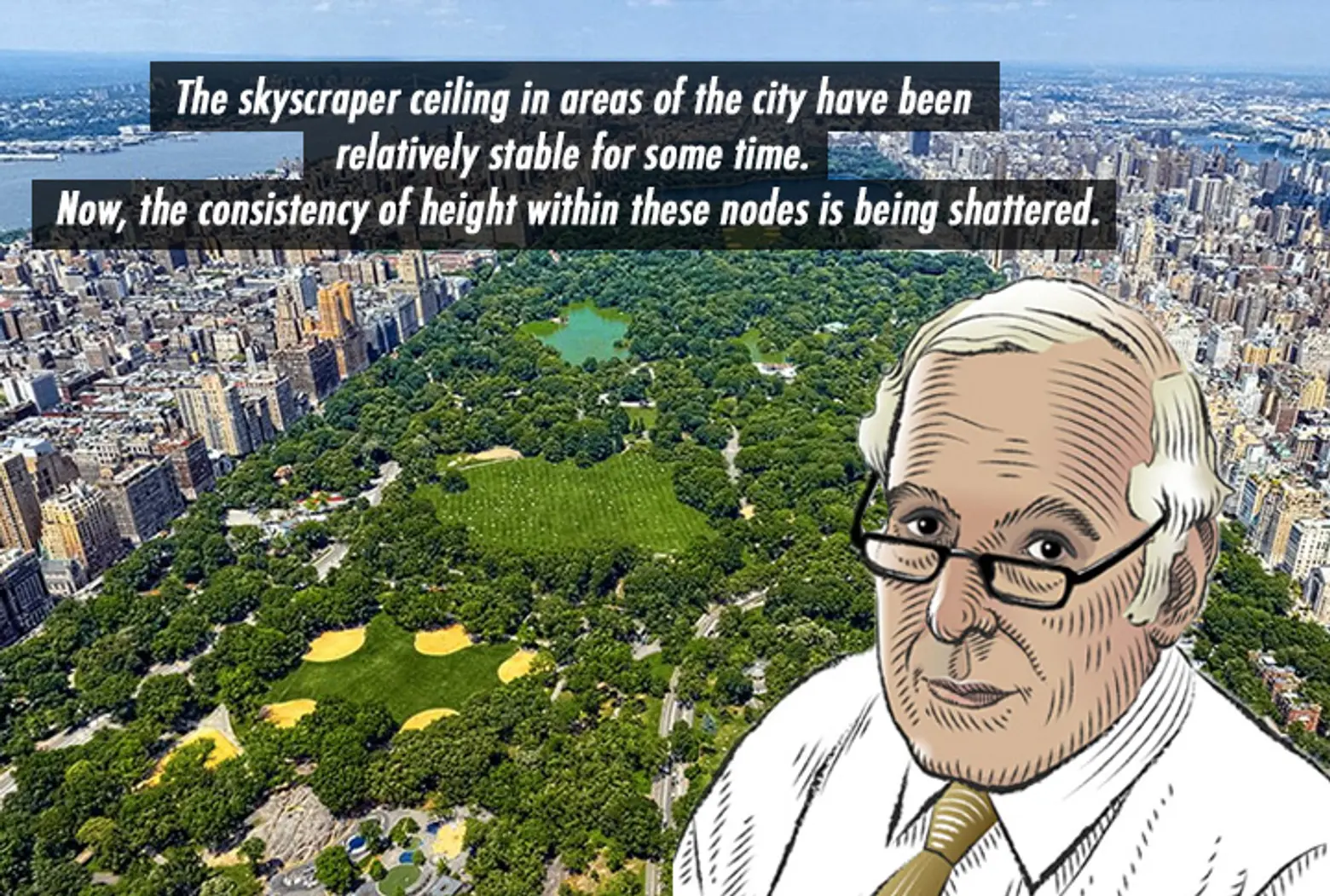

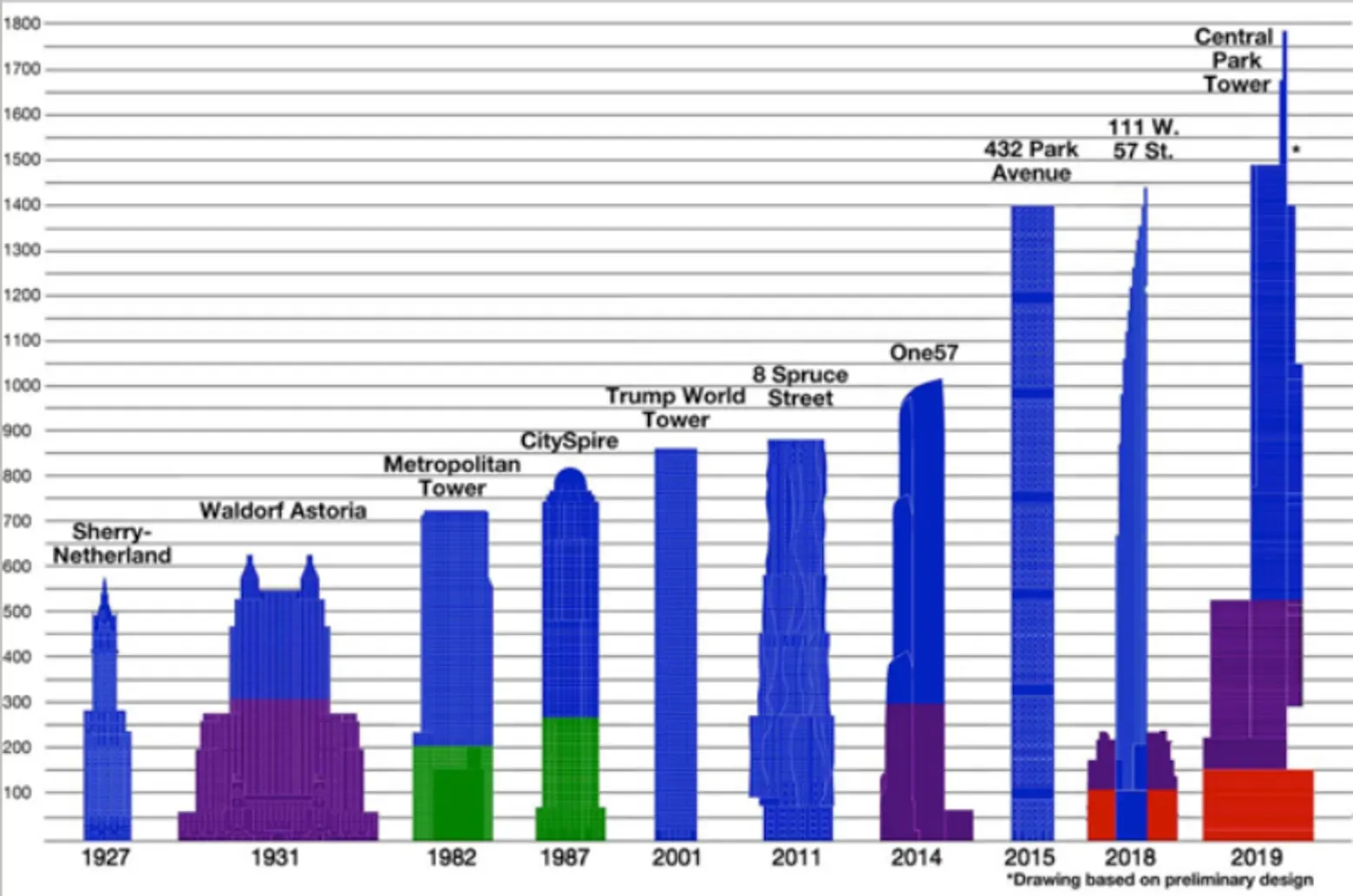

Historically, there has been a rather steady escalation of building heights in clustered areas such as the Financial District around the stock exchange, the 42nd Street corridor near Grand Central Terminal, and more recently around Times Square and the Plaza District. The skyscraper ceiling in these areas have been relatively stable for some time. Now, the consistency of height within these nodes is being shattered. The chart below created by The Skyscraper Museum shows the chronological growth of the city’s tallest residential buildings over the last 88 years: blue is the residential building component, purple is hotel, green is office and orange is retail.

Illustration courtesy of The Skyscraper Museum

One could argue that the new very slender buildings are merely echoing the svelte aesthetic of the Sherry Netherlands Hotel on Fifth Avenue and are not aping the mammoth masses of 9 West 57th Street and the General Motors Building or One Chase Manhattan Plaza. When the huge Time Warner Center at Columbus Circle was erected after years of controversy over shadows that might be cast on Central Park by other plans for the site, it was considered a massive mixed-use project—but it gave new life to the area.

The new supertalls are unlikely to become as important an engine for revitalization as Time Warner was, and shadows have faded quite a bit from the urban planning agenda, but the towers in this corridor will become an undeniable source of amazement for their engineering and economics and chutzpah.

Their marketing success is also probably not as problematic as other mega-towers in areas such as the Hudson Yards because of the desirability of being close to Central Park, Bergdorf Goodman and the Whole Foods cellar at Time Warner Center. Presumably, these aeries will attract pale male and kindred hawks and not vultures—and personally, I feel a few decorative gargoyles wouldn’t hurt either.

Ahead, I’ll take you through the major supertall projects in play along Central Park South, the 57th Street corridor that has come to be known as Billionaires’ Row.

+++

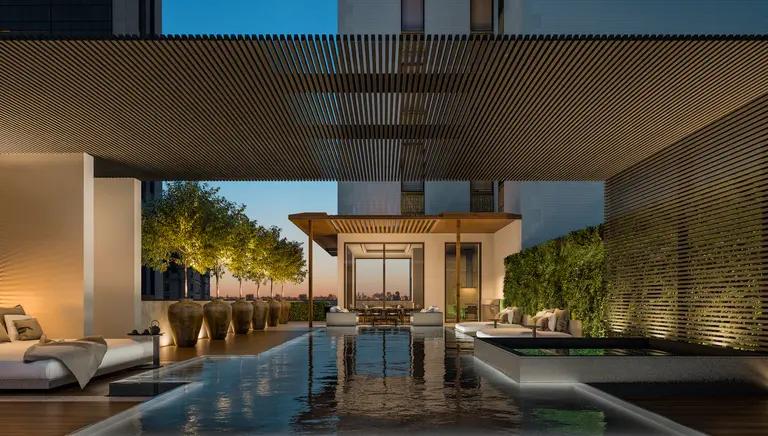

Image © Wade Zimmerman courtesy of Agence Christian de Portzamparc (ACDP)

Image © Wade Zimmerman courtesy of Agence Christian de Portzamparc (ACDP)

One57: 157 West 57th Street

Extell, one of the city’s most active developers in recent years, started the new tall building binge in the Plaza district with his One57 mixed-use tower at 157 West 57th Street designed by Christian de Portzamparc, who designed his Riverside Center master plan further west near the Hudson River, the 23-story LVMH tower at 21 East 57th Street for Bernard Arnault and the very prismatic, glass-clad tower at 400 Park Avenue South at 28th Street for Albert Kalimian that was recently competed by Equity Residential and Toll Brothers.

The 1,004-foot-high tower opened this year as the first of the current crop of supertalls. It has curved tops and a rippling, basket-weave base on 57th Street. With its “pixelated” sides, de Portzamparc’s blue mid-block building, which extends through to 58th Street, now towers over the Central Park South skyline and its various setbacks and roof are softly curved: the architect romantically envisioned it as a “cascading waterfall.”

Rendering shows One57 just to the north of the area’s “tuning fork” trio of towers that were the area’s tallest including the dome-topped CitySpire at the left, the black, angled Metropolitan Tower and the Post-Modern Carnegie Tower.

The New York Times’ resident architecture critic Mr. Kimmelman was not enamored with One57, noting that it was “a heap of volumes, not liquid but stolid, chintzily embellished, clad in acres of shadow-blue glass offset by a pox of tinted panes, like age spots.” How well it will age, especially when it is surrounded by its much taller neighbors, is anybody’s guess, but the odds are that its rippling ribbons at the base and soft curved tops will gain it brownie points with some observers.

Extell’s One57 took most people by surprise. It went up without having to pass the severe gauntlet of the city’s “uniform land use process” known as ULURP because it was an “as-of-right” project that required no pubic approvals.

Its pale-blue facades were a bit gaudy for the elegant surroundings of Carnegie Hall and nearby Bergdorf Goodman, but its basket-weave base and two marquees on 57th Street were impressive design flourishes. One of the entrances was for the Park Hyatt Hotel in the building’s base and other was for the expensive condominiums at the top that were regularly in the news.

And Extell may not be finished with 57th Street. In May, Crain’s reported that the Calvary Baptist Church may sell its sanctuary and 197-room Salisbury Hotel at 123 West 57the Street to the developer. Extell has already bought three other buildings on the block and is negotiating buyouts with rent-regulated tenants. “Extell’s plans have not been made public, but observers believe the collection of parcels could permit a project similar in scale to its 75-story One57 a few doors down,” the article said.

One57’s fame was a bit short-lived, however, as Harry Macklowe and some partners tore down the elegant Drake Hotel and commissioned Rafael Vinoly to erect a tall tower simply addressed as 432 Park Avenue. Although its Central Park vistas are more central, One57 is outgunned by 432’s altitude and visual rigidity—even though its appearance is still very hard to evaluate because its windows are covered and its many “scoops” by indented mechanical floors are not fully exposed.

The 1,396-foot-tall tower is currently the tallest residential building in the world and is nearing completion. The 96-story skyscraper was recently topped out and now towers over its neighbors when viewed from the Great Lawn in Central Park, completely unsurpassed.

Although there is a low-rise retail base on 57th Street, Vinoly’s tower rises without setbacks and has symmetrical facades with windows that are about 10-feet-square. The white tower’s facades are smooth concrete although from a distance they appear to be the purest marble. The design is very minimalist with a flat top, although some observers keep hoping a Chrysler Building spire will emerge at the last minute from within the building, which is not the least bit likely.

Surprisingly, and sadly, the building’s low-rise frontage on 57th Street and its “bustle” on the northwest corner of 56th Street and Park Avenue bear no relation whatsoever to the tower whose high velocity is awesome if not poetic and beautiful. Indeed, final judgment must be withheld until the reflectivity and transparency of its covered-up windows must be observed from many angles, at different times, and in different weather. But at the very least, perhaps they might consider mounting a version of the 12-foot-high rooster weathervane that topped the 412-foot-high, glorious, gilded pyramid roof of the Crown Building on the southwest corner of 57th Street and Fifth Avenue until it was removed in 1942 to be melted down for the WWII effort.

Rendering of 111 West 57th Streetth Street showing its extremely thin ornamental top with One57 at left

Rendering of 111 West 57th Streetth Street showing its extremely thin ornamental top with One57 at left

432 Park’s reign as the loftiest residential skyscraper will eventually come to an end when it is eclipsed in height by the 1,428-foot-high 111 West 57th Street tower of JDS Development and Property Markets Group. The slenderest “pencil” or “toothpick” of the city’s new sky-high developments has been designed by SHoP Architects who became famous a decade or so ago with their very fine, black, squat and illuminated design of a black addition to a warehouse on the southeast corner of Ninth Avenue and 15th Street, known as Porter House.

Its design on 57th Street for JDS is a tower that is only about two-thirds as thick—for much of its height—as 432 Park Avenue. It has many setbacks on its south façade, and none on its north. Its east and west facades are wavy grills of terracotta and bronze, a frilly evening gown swaying to the city’s rhythms were it not for a “hidden” tuned-mass-damper holding it generally steady. There are only 60 apartments in the tower and an additional 14 in the mid-rise adjoining former Steinway Building.

The development is described as an 80-story tower, and like many of the other supertalls, the traditional correlation between building height and number of floors is not straight-forward due to higher ceilings and lobbies and amenity spaces and vacant spaces. In this building, the “vacant spaces” constitute a lot of floors at the very top of the building where it thins out extremely. In the old days, floor confusion was simply a developer’s way of getting more marketing clout in some mixed-use buildings but the new method of floor counting is a bit more puzzling.

The Central Park Tower: 217 West 57th Street

The tallest of this group of supertalls is the Central Park Tower (originally known as the “Nordstrom Tower” after the retailer which is occupying much of its base) located at 217 West 57th Street. The building is Extell Developments second coming to Billionaire’s Row and is now finally rising after many months of foundation work. The tower was originally planned to soar 1,775 feet tall with its spire—just one foot shorter than One World Trade Center’s—but back in September the spire was reported to be eliminated. Without it, the tower will only be 1,550 feet tall.

The Central Park Tower is the most asymmetric of the new supertalls and part of its east façade will cantilever high over the French Renaissance-style, low-rise Art Students League that was designed in 1892 by Henry H. Hardenbergh, the architect of the Plaza Hotel whose prestige gave its name to the Plaza Office District. The Central Park Tower is being designed by Adrian Smith and Gordon McGill, who, as I previously mentioned, designed the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

In his “Critic’s Notebook” December 22, 2013 column in The New York Times, Michael Kimmelman wrote of the relationship between the Extell tower and the league’s building: “Picture a giant with one foot raised, poised to squash a poodle.”

Jean Nouvel’s 53 West 53rd Street’s top 200 feet were decapitated by Amanda Burden when she was chairman of the City Planning Commission—and this rendering shows the stunted result.

Jean Nouvel’s 53 West 53rd Street’s top 200 feet were decapitated by Amanda Burden when she was chairman of the City Planning Commission—and this rendering shows the stunted result.

Jean Nouvel’s design for 53 West 53rd Street is the most vigorous of the lot even in its significantly diminished height—although it has retained much of its design identity of diagonal braces and pointed tops, a look conceived more than a decade ago.

In its decision to cut down Nouvel’s muscular, mid-block tower by 200 feet to 1,050 feet, Amanda Burden of the City Planning Commission maintained that it was inappropriately high to be so close to the Empire State Building. Given that it was about a mile away, that argument was most ornery, especially since the commission has not used the same argument about the Hudson Yards tall towers or SL Green’s proposed One Vanderbilt—all of which are much closer to the Empire State Building than 53 West 53rd Street, and none of which are nearly as aesthetically captivating.

It will be interesting to see if the City Planning Commission will invoke Burden’s pre-emptory strike against the interesting Nouvel tower for another one just down the block that press reports indicate will be about 1,400 feet high and replace one of the city’s few metal buildings, 666 Fifth Avenue. The New York Post reported in September that Jared Kushner and Steven Roth of Vornado want to “reposition” the 1957 aluminum-clad office and retail tower with “a 1,400-foot-high vertical mall, hotel and residential tower,” adding that Zaha Hadid “has already prepared a scheme that would restack the current 39-story building into a slender, super-tall hotel and residential tower above a vertical retail podium.”

In recent years, the building’s base has been drastically altered to accommodate an ever-changing roster of retailers even though its original configuration was one of the handsomest in the city’s history. The building, which is on a former site of Richard Morris Hunt’s 1882 house for William K. Vanderbilt, was designed by Carson & Lundin.

Rendering of 220 Central Park South with Time Warner Center at left and Central Park at right

Rendering of 220 Central Park South with Time Warner Center at left and Central Park at right

220 Central Park South & 520 Park Avenue

The two most “New York” new towers are 220 Central Park South and 520 Park Avenue, both designed by Robert A. M. Stern, the architect of the very successful—but quite modest in terms of height—15 Central Park West. Neither break the 1,000-foot-mark, but both will be very highly visible and very slender on the midtown skyline, and both have Stern’s elegant, post-modern flourishes.

At 950 feet, the 65-story 220 Central Park South, which rises on 58th Street behind a large driveway adjacent to its 17-story shorter tower, has gentle curves on its north and south facades and a lovely and very impressive, fluted top. Stern first used the unusual papa-bear-and-cub site plan at 15 Central Park West and it didn’t inhibit its soaring price records.

Vornado is the developer of this 118-unit residential condominium tower and for several years was stymied in its development because Extell had bought the lease for the garage of the apartment building on the site. Finally, the two developers agreed in the fall of 2013 for Vornado to pay Extell $194 million for the garage and some additional air rights so that Vornado could shift its tower a bit to the west and Extell could shift its tower (via its cantilever) a bit to the east and enable its Nordstrom to have larger floors.

Rendering of 520 Park Avenue at left looming over 515 Park Avenue at right

Rendering of 520 Park Avenue at left looming over 515 Park Avenue at right

At the asymmetrical 520 Park Avenue, Arthur and William Zeckendorf, and their partner Global Holdings commissioned Stern to build the smallest of the new crop of supertalls: a 781-foot-high spire with only 31 apartments that will soar over the Zeckendorf-built 515 Park Avenue—which was once the tallest building on Park Avenue on the Upper East Side. The 51-story, 520 Park will have an extravagant lobby/salon/garden suite and will be very highly visible despite its relatively short stature.

1 Park Lane: 36 Central Park South

Not to be left out of the big race, the Witkoff Group teamed up with Jynwei Capital, New Valley LLC, Highgate Holdings and Macklowe Properties to buy the famed 47-story, Helmsley Park Lane Hotel in November, 2013 for $660 million. Various press reports indicated the Witkoff’s architect might be Rafael Viñoly, then Gary Handel, then Richard Rogers, and, most recently, Herzog & de Meuron, the architects of 56 Leonard Street and 40 Bond Street. Details remain sketchy, but some reports state that the tower will rise about 1,210 feet with about 90 condominium apartments.

+++

Carter is an architecture critic, editorial director of CityRealty.com and the publisher of The City Review. He worked for 26 years at The New York Times where he covered real estate for 14 years, and for seven years, produced the nationally syndicated weeknight radio program “Tomorrow’s Front Page of The New York Times.” For nearly a decade, Carter also wrote the entire North American Architecture and Real Estate Annual Supplement for The International Herald Tribune. Shortly after his time at the Tribune, he joined The New York Post as its architecture critic and real estate editor. He has also contributed to The New York Sun’s architecture column.