10 things you might not know about Riverside Park

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. (1887 – 1964). Parks – Riverside Park – West 122nd Street; Via NYPL Digital Collections

Riverside Park is the place to be whether you want to bask in the sun at the 79th Street Boat Basin, pay respects at Grant’s Tomb, or do your best T. Rex at Dinosaur Playground. Did you know that the park’s history is as varied as its charms? From yachts to goats to cowboys, check out 10 things you might not know about Riverside Park!

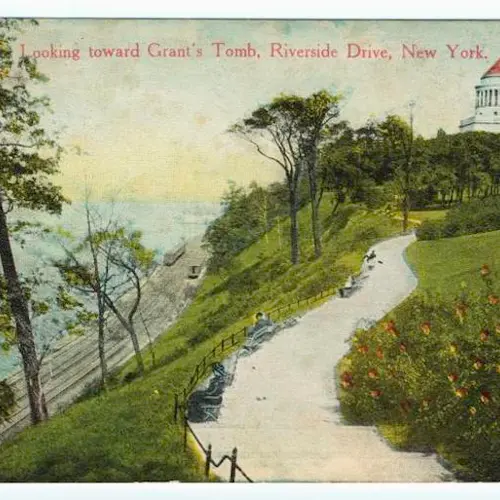

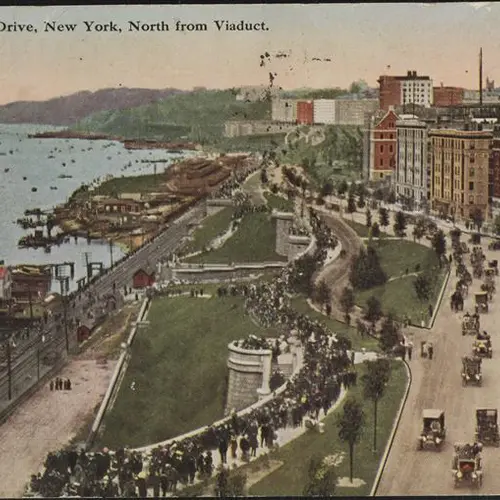

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1905). Riverside Park and Drive; via NYPL Digital Collections

1. It was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux of Central Park fame

In 1865, the Central Park Commissioners were tasked with laying out streets in Manhattan north and west of Central Park. That year, Commissioner William R. Martin proposed a scenic carriage drive and park along the Hudson River to spur development of the Upper West Side.

Frederick Law Olmsted was the natural choice to design the new park (and Riverside Drive) because he had pioneered the profession of Landscape Architecture and was working in-house for the New York City Parks Department. His design for the park extended from 72nd to 129th Streets.

When the Tammany Ring ousted Olmsted from the Central Park Board in 1878, his longtime professional partner, Calvert Vaux, took over the design and execution of Riverside Park. Olmsted and Vaux had worked together to design a number of parks around New York City, including Central Park, Prospect Park, Morningside Park, and Fort Greene Park. Vaux and the Parks Department continued to work on Riverside Park for the next 25 years, landscaping the area in the Rustic English Garden style.

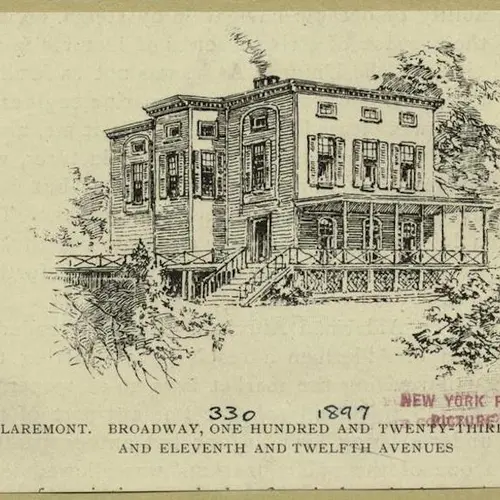

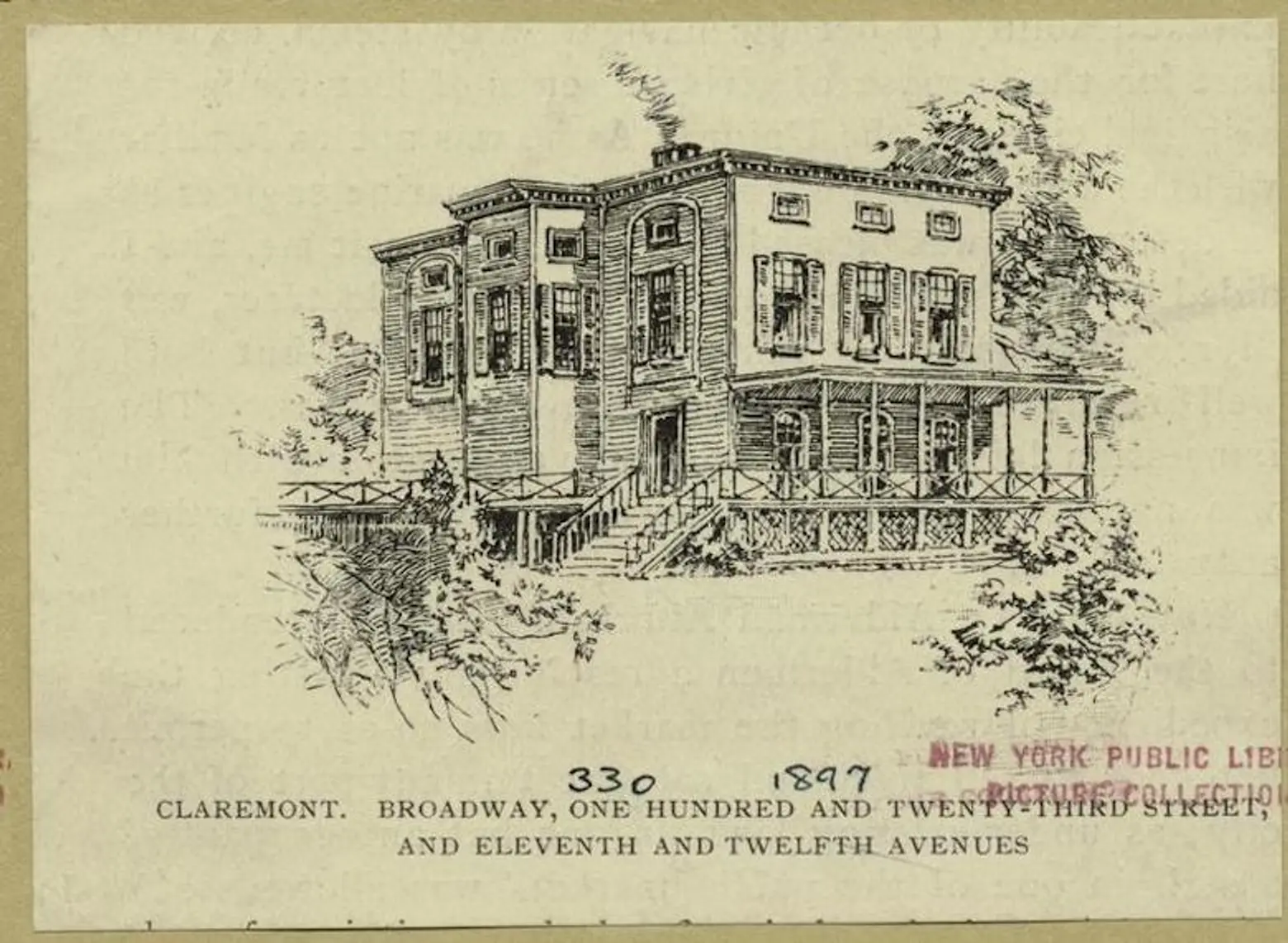

Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1897). Claremont Tavern, New York, 19th Century; Via NYPL Digital Collections

2. It was once home to the most famous inn in the country

Claremont Inn, which once stood at 125th Street, was the original terminus of Riverside Drive. Olmsted designed the meandering carriage drive to come to a halt at Claremont Inn because the stately building was one of the most famous gathering places in the country.

The inn was built around 1806 as an estate. When it was converted into a restaurant and inn, it catered to a rotating roster of glitterati including assorted Astors and Vanderbilts. Presidents frequented the inn so often that it’s said William Howard Taft had his own chair on site, specifically designed to accommodate his “portly person.” The Inn flourished into the 20th century, but its star dimmed in the post-war years. Eventually, it caught fire and was demolished in the early 1950s.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. (1775 – 1890). The Battle of Harlem Heights, September 16, 1776; Via NYPL Digital Collection

3. George Washington suggested it as the site for the US Capitol

George Washington became familiar with the area that is now Riverside Park during the Battle of Harlem Heights. After the Revolution, he suggested that the US Capitol be built on the hill north of where Grant’s Tomb now stands because the hill provided an appropriately powerful landscape.

4. The land it occupies was once home to more goats than people

“Gotham” actually means Goat’s Town in Anglo-Saxon. Washington Irving, who popularized the term as a nickname for New York City, was teasing his fellow New Yorkers, but on the West Side, the name was apt. Before the Upper West Side was developed into the neighborhood we know today, it was largely open farmland, home to squatters and their goats.

Mount Tom via Google Street View

5. Its rocky bluffs inspired Poe’s “The Raven”

And amongst the goats there flew a Raven. Between 1844 and 1845, Edgar Allan Poe lived at Brennan’s Farmhouse and composed “The Raven” at what is now 84th Street and Broadway. The farmhouse has long since been demolished, but you can still find the spot where Poe pondered weak and weary. In Riverside Park, just off 83rd Street, you’ll find a rocky outcropping of Manhattan Schist known as Mount Tom. Poe himself named the stone after Tom Brennan, son of his hosts at the Farmhouse. Poe would sit on the rock of hours, gazing at the Hudson. He pronounced the view “sublime.”

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library; via NYPL Digital Collections

6. It was the starting point for the first flight over Manhattan

1909 marked the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s voyage aboard the Half Moon into New York Harbor, and the City partied hard. During the celebration, ships from all over the world set anchor in the Hudson, docking from 42nd Street to Stuyten Duyvil. To cap off the festivities, Wilbur Wright flew from Grant’s Tomb to Governor’s Island and back. It was the first flight over Manhattan Island.

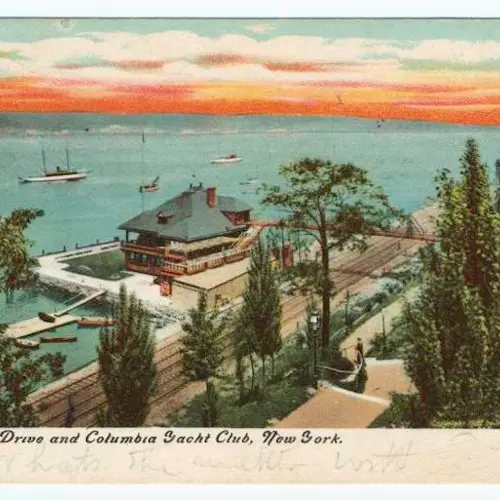

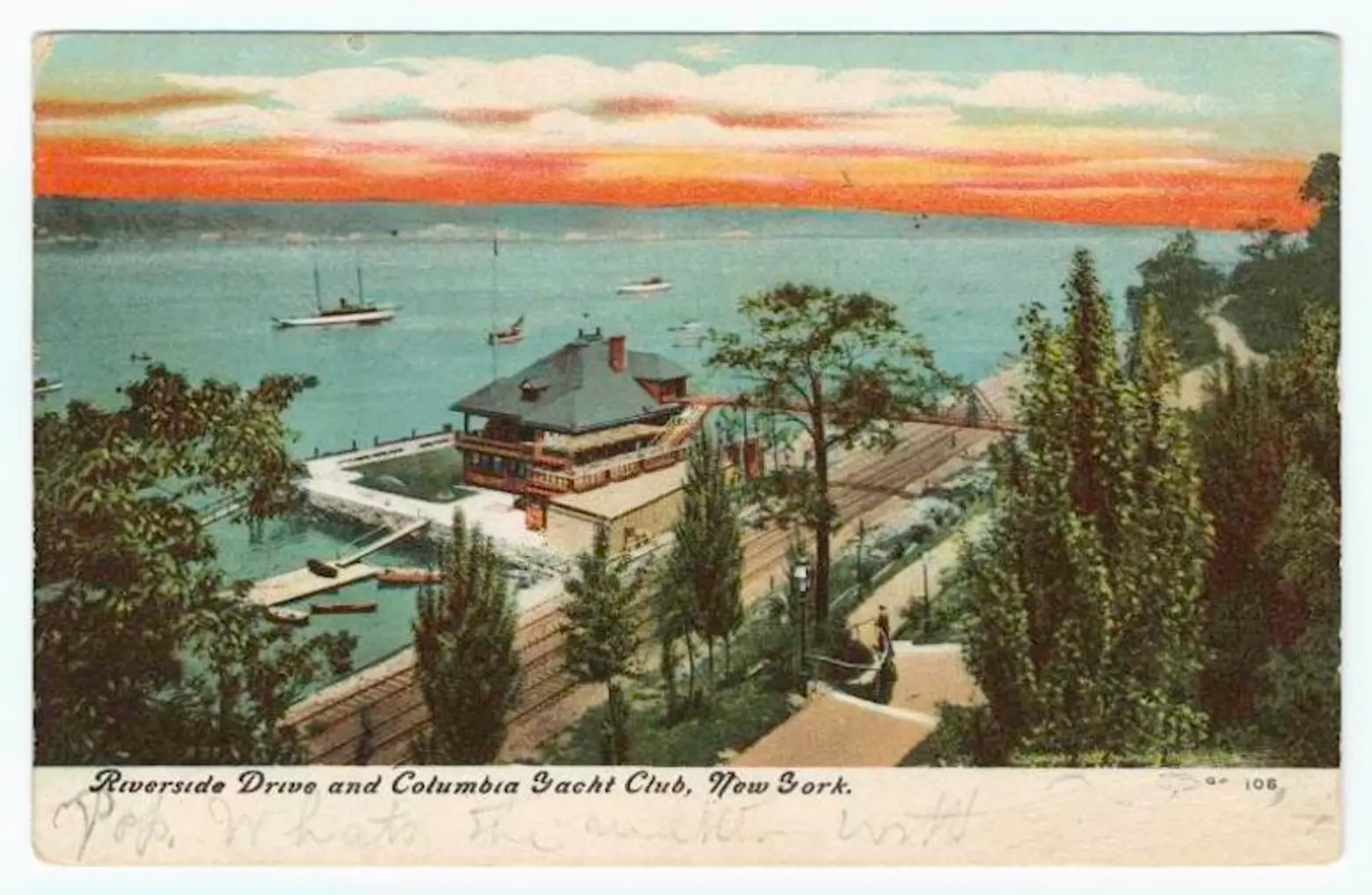

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1902). Riverside Drive and Columbia Yacht Club; Via NYPL Digital Collections

7. It was once home to a Yacht Club

Before the Park had planes, it had yachts. The Columbia Yacht Club built its clubhouse in the park at the foot of 86th Street and played host to visiting dignitaries and Naval delegations. The club survived into the 1930s, when Robert Moses demolished it as part of his Westside Improvement project.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1905). Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, Riverside Drive, New York; Via NYPL Digital Collection

8. It welcomed Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet home after its round-the-world-tour

One of the greatest Naval flotillas ever to sail the Hudson was Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet, which docked in the river in 1909 when it returned from a worldwide goodwill tour. Riverside Park’s Soldiers and Sailors monument was lit up for the occasion, serving as a beacon for the fleet.

9. It was once patrolled by “West Side Cowboys”

We’ve talked about planes and yachts, but the longest standing mode of transport in Riverside Park was the railroad. The New York Central Railroad established its freight line along the Hudson River in 1846.

The industrial railroad turned the area into the Wild West (Side)! The bustle of freight trains, horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians made 11th Avenue so dangerous it was known as “Death Avenue.” The frightening thoroughfare was patrolled by a cadre of “West Side Cowboys,” who rode the tracks ahead of the freight trains waving a red flag to warn commuters about oncoming locomotives.

The construction of the Henry Hudson Bridge (1936) was a part of the West Side Improvement project; via Wikimedia

10. Its 1930s expansion was one of the largest Public Works projects in American History

Since the 1890s, West Siders and city planners alike had tried to cover the railroad tracks and beautify Riverside Park. But the enormous cost of the project stopped all such plans in their tracks until 1934. That year, Robert Moses marshaled millions of dollars in state and federal funds to finance the West Side Improvement. His plan included expanding Riverside Park, and creating the Henry Hudson Parkway and the Henry Hudson Bridge. The entire project cost between $109 and $218 million in 1934 dollars, a then-unprecedented sum for public works.

Moses executed his West Side Improvement in just three years and added a host of celebrated spots to Riverside Park, including the 79th Street Boat Basin and scores of sports courts and ball fields. But he confined his improvements to the area of the park south of 125th Street, which he believed was most likely to be used by white residents.

Since Moses’s tenure, both the City and its residents have worked to make Riverside Park a more equitable resource for all West Siders. Today, the Riverside Park Conservancy supports and maintains the park as a community hub.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.