10 things you never knew about Frank Lloyd Wright

Considering today would have been Frank Lloyd Wright‘s 150th birthday, you’d think we all know everything there is to know about the prolific architect. But the wildly creative, often stubborn, and always meticulous Wright was also quite mysterious, leaving behind a legacy full of oddities and little-known stories. In honor of the big day, 6sqft has rounded up the top 10 things you likely never knew about him, including the mere three hours it took him to design one of his most famous buildings, the world-famous toy that his son designed, his secondary career, and a couple present-day ways his work lives on.

▽▽▽

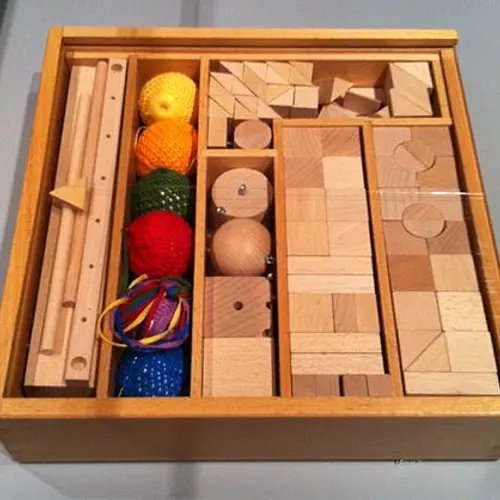

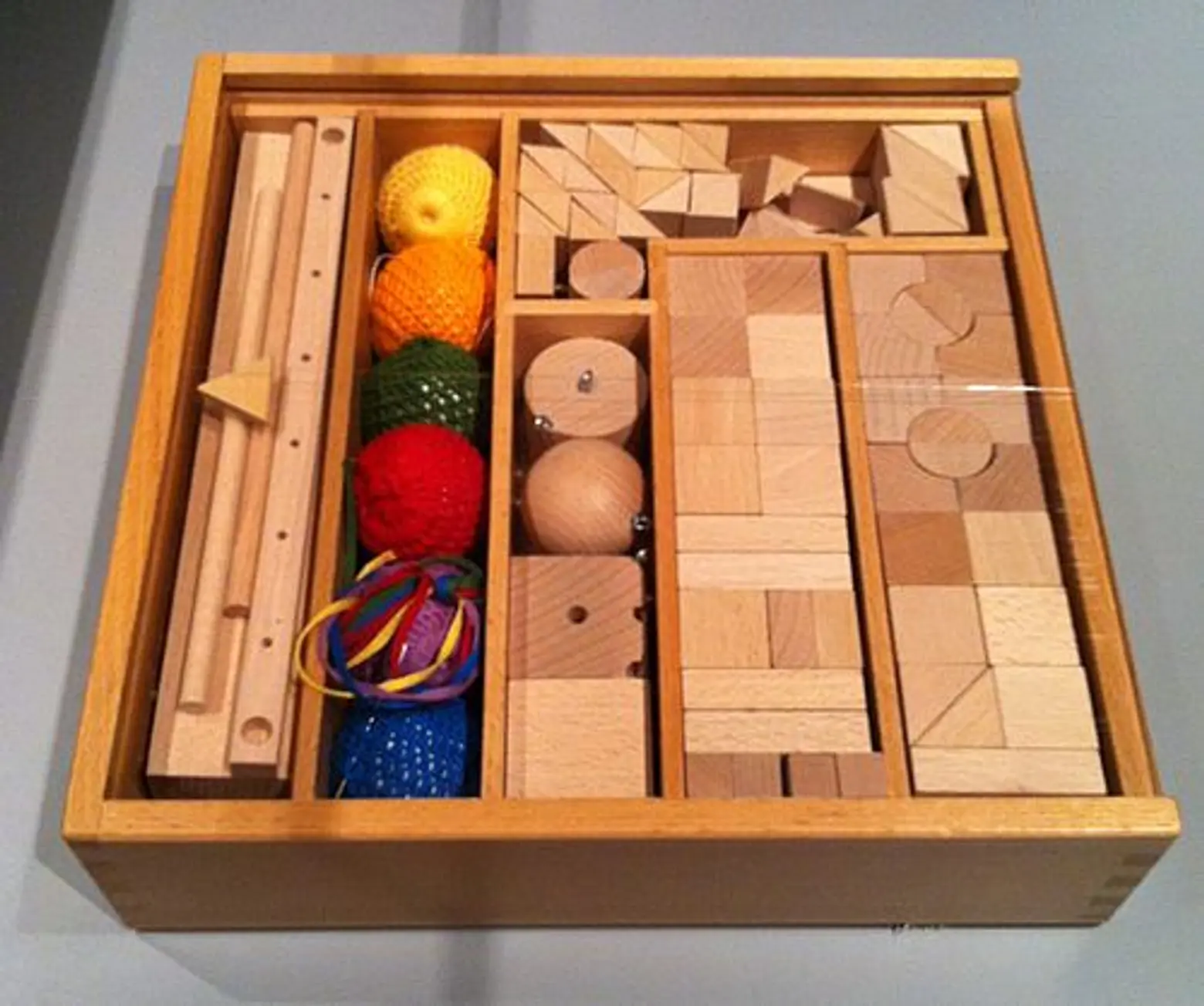

A replica of an original set of Froebel Gifts via Wiki Commons

A replica of an original set of Froebel Gifts via Wiki Commons

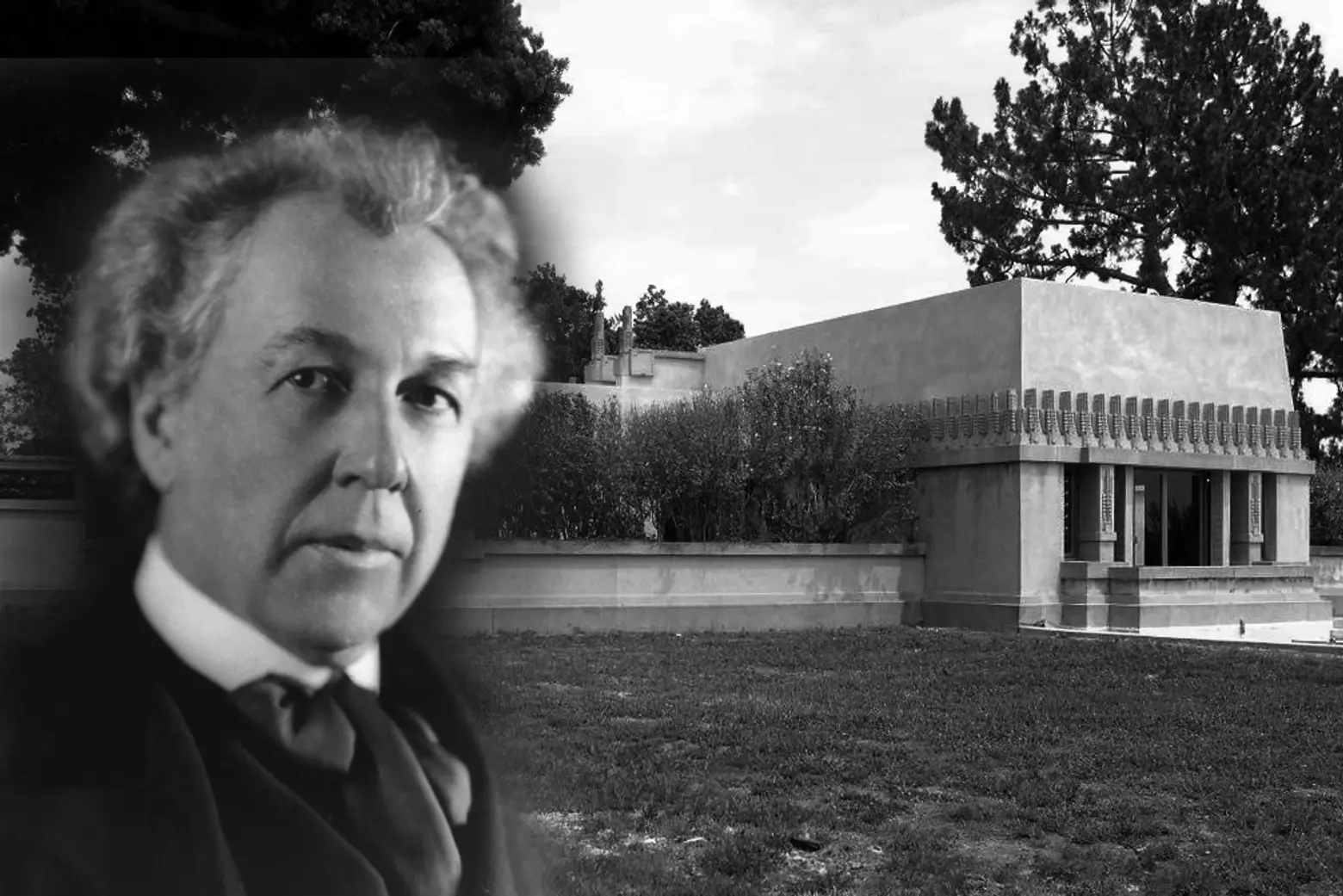

1. His architecture career began in the womb

Biographies on Wright note that when his mother was pregnant with him she vocalized that her son would grow up to create beautiful buildings. She even hung up engravings of English cathedrals in his nursery as inspiration. Then, in 1876, she visited the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, where she saw the educational geometric blocks known as Froebel Gifts. She bought a set for her son, and he later described their influence on his career in his autobiography: “For several years I sat at the little Kindergarten table-top… and played… with the cube, the sphere and the triangle—these smooth wooden maple blocks… All are in my fingers to this day… ” And it’s a good thing his mother made this impressin on him early, considering he never graduated from high school or college.

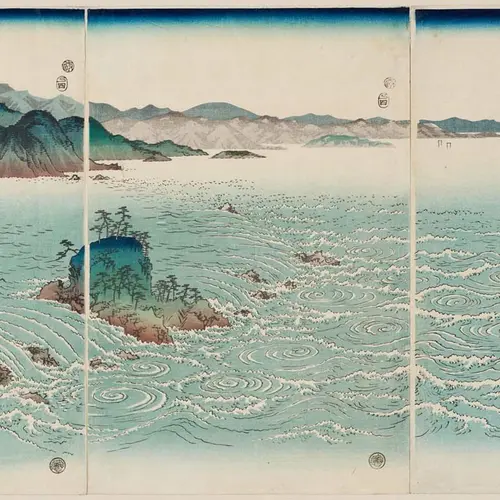

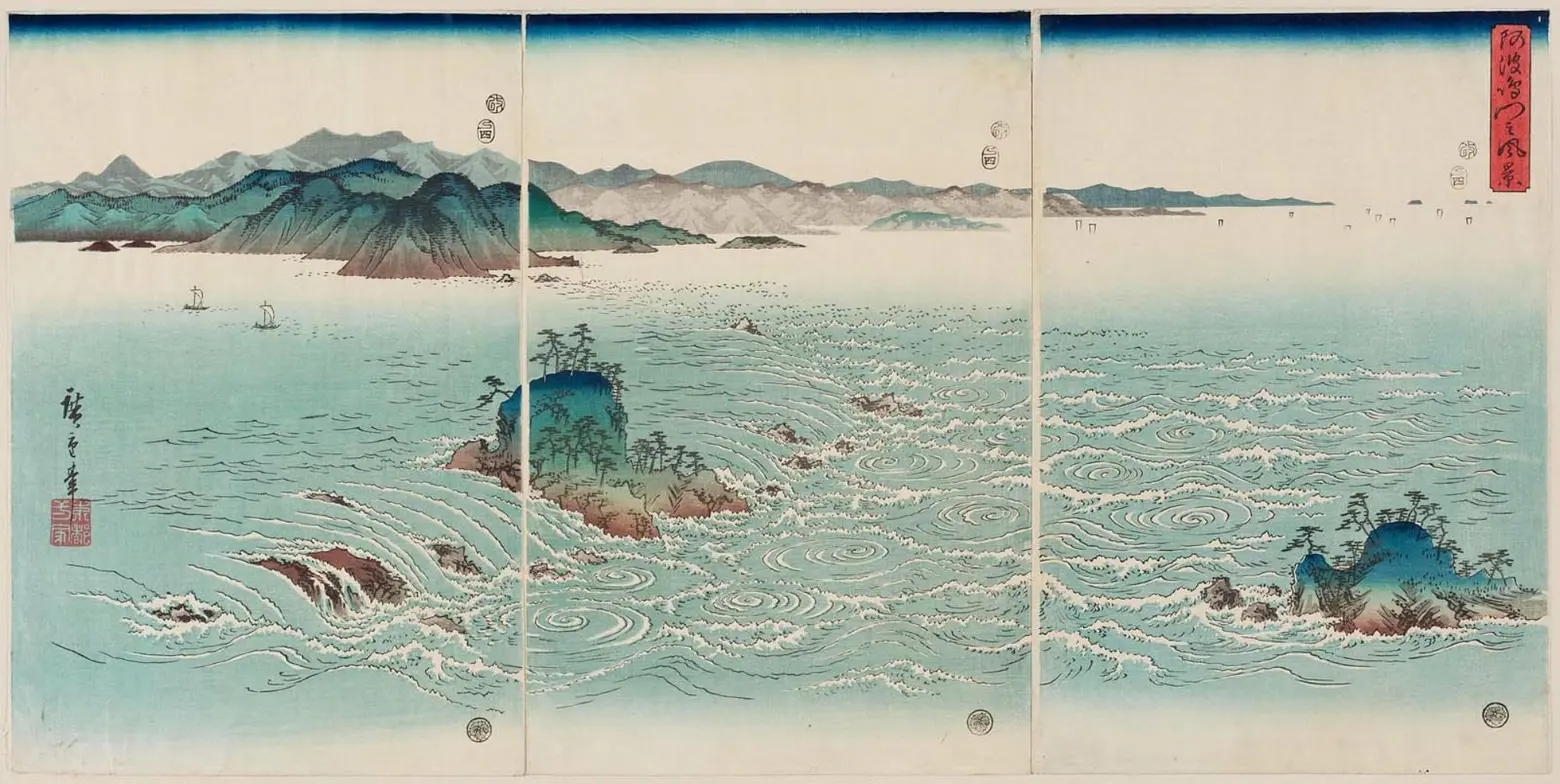

Utagawa Hiroshige’s “View of the Whirlpools at Awa” via Wiki Commons

2. He was also a Japanese art dealer

When the architect passed away at the age of 91, he had a personal collection of 6,000 Japanese woodblock prints. In fact, during the Depression, he earned more from selling art than from architecture. His fascination began at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where he saw the Japan pavilion. He made his first trip to the country in 1905, returning with hundreds of ukiyo-e prints.

In his book titled “The Japanese Print,” he wrote, “A Japanese artist grasps form always by reaching underneath for its geometry, never losing sight of its spiritual efficacy. These simple coloured engravings are indeed a language whose purpose is absolute beauty.” He wanted to bring this passion to mainstream America, and in 1906 he exhibited his large collection of Utagawa Hiroshige (the Japanese artist is considered the last great master of the ukiyo-e tradition) at the Art Institute in Chicago. Two years later, he loaned more pieces to the museum in what was then the largest display of Japanese prints and personally designed the exhibit down to the frames.

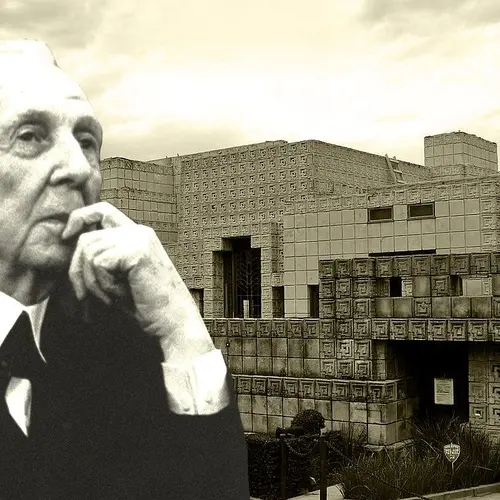

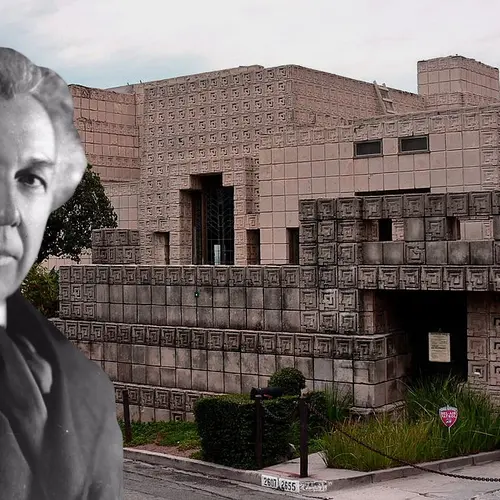

The Imperial Hotel’s entrance courtyard, which Wright designed in the Maya Revival Style, via Wiki Commons

In 1915, Wright opened an office in Japan–“At last I had found one country on earth where simplicity, as nature, is supreme,” he said. He lived part time in Tokyo while building the Imperial Hotel from 1917 to 1922, during which time his dealing hit a high. When he returned to the U.S., he began selling his prints to clients, convincing them that the traditional bird and flower motifs complemented his organic, streamlined interiors.

3. He published 20+ books to avoid bankruptcy

It’s rumored that when he moved to Chicago in Chicago in 1887, FLW was so poor that he ate only bananas until he found a job. But this fruit-only diet didn’t show him the value of a dollar; for most of his career, he was on the brink of bankruptcy, partly due to his taste for fast cars and expensive suits. To bring in extra cash, Wright published more than 20 books, including one on Japanese art, an autobiography, and his more well-known titles like “The Disappearing City,” in which he first proposed the idea for his Broadacre City concept.

Via Passive House +

4. In 2007, a Frank Lloyd Wright design was erected in Ireland

Just before his death in 1959, Wright completed a residential design for Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert Wieland of Maryland, but after the couple ran into financial trouble, it was never built. Fast forward nearly 50 years and Marc Coleman of Greystones, County Wicklow, Ireland finally had the home erected halfway around the world. When he decided he wanted a home designed by the late architect, he contacted the Chicago-based Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Since Wright’s designs were almost always site-specific, designed around the natural setting of his commissions, the Foundation offered four of a total of 380 unbuilt designs to Coleman.

Once he selected the Wieland design, the Foundation mandated that Coleman consult with an architect who had worked directly with Wright. So, his consultant was E. Thomas Casey, who studied under Wright at Taliesin West and eventually went on to become the founding dean of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture at Taliesin West and the structural engineer for the Guggenheim. Casey provided 18 drawings of the project and event spent three days in Ireland with Coleman (unfortunately, he passed in 2005, eighteen months before construction began).

Via the Penfield House

Via the Penfield House

5. And you can still buy his last residential project

In 1955, Wright completed the Penfield Home in the Cleveland, Ohio suburb of Willoughby Hills for art teacher Louis Penfield. The Usonian home sits on 18.5 acres and was built to accommodate its owner’s 6’8″ height; it has 12-foot ceilings and a floating staircase–unusual elements for the architect who usually kept things squat and compact. Penfield also owned the adjacent 10.7-acre parcel, for which Wright designed another home. But the plans for this second commission were still on the architect’s desk when he died unexpectedly in April of 1959.

Louis hired Wright’s apprentice Wes Peters to finish the blueprints, but never went ahead with construction of the second home. His son Paul has been renting out the Penfield Home since 2003 to visitors who pay upwards of $275/night. But in 2014, he listed it for sale for $1.7 million, which also includes a cottage and farmhouse on the site, as well as the lot and blueprints for the unbuilt project that Louis dubbed Riverrock for the fact that Wright planned to construct it with rocks from the nearby Chagrin River. As the listing explains, “the only unbuilt Wright Project for which the client-architect relationship is both proven and paid for, along with the very land upon which it was meant to stand,” which still includes the poplar tree around which the house was oriented.

3D rendering of Riverrock via Archilogic

3D rendering of Riverrock via Archilogic

Recently, 3D modeling company Archilogic created a 3D tour of Riverrock, which shows interested parties aerial, floorplan, and in-person views of the could-be-built home, along with a better look at its notable wedge-shaped roofline that resembles a yacht’s bow jutting out toward the River.

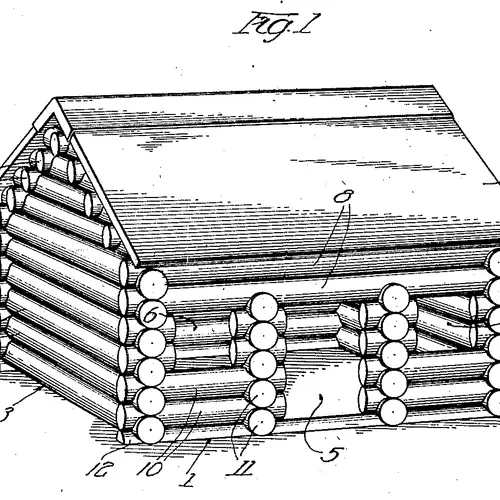

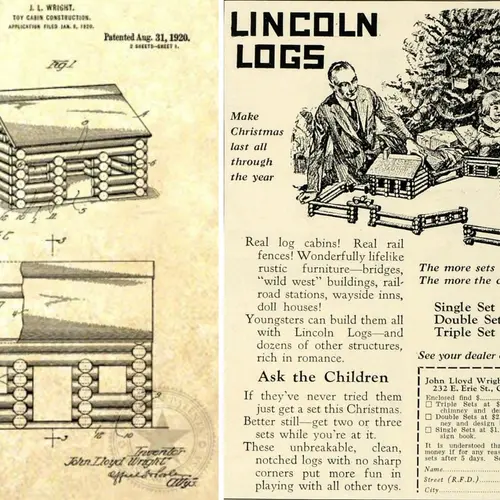

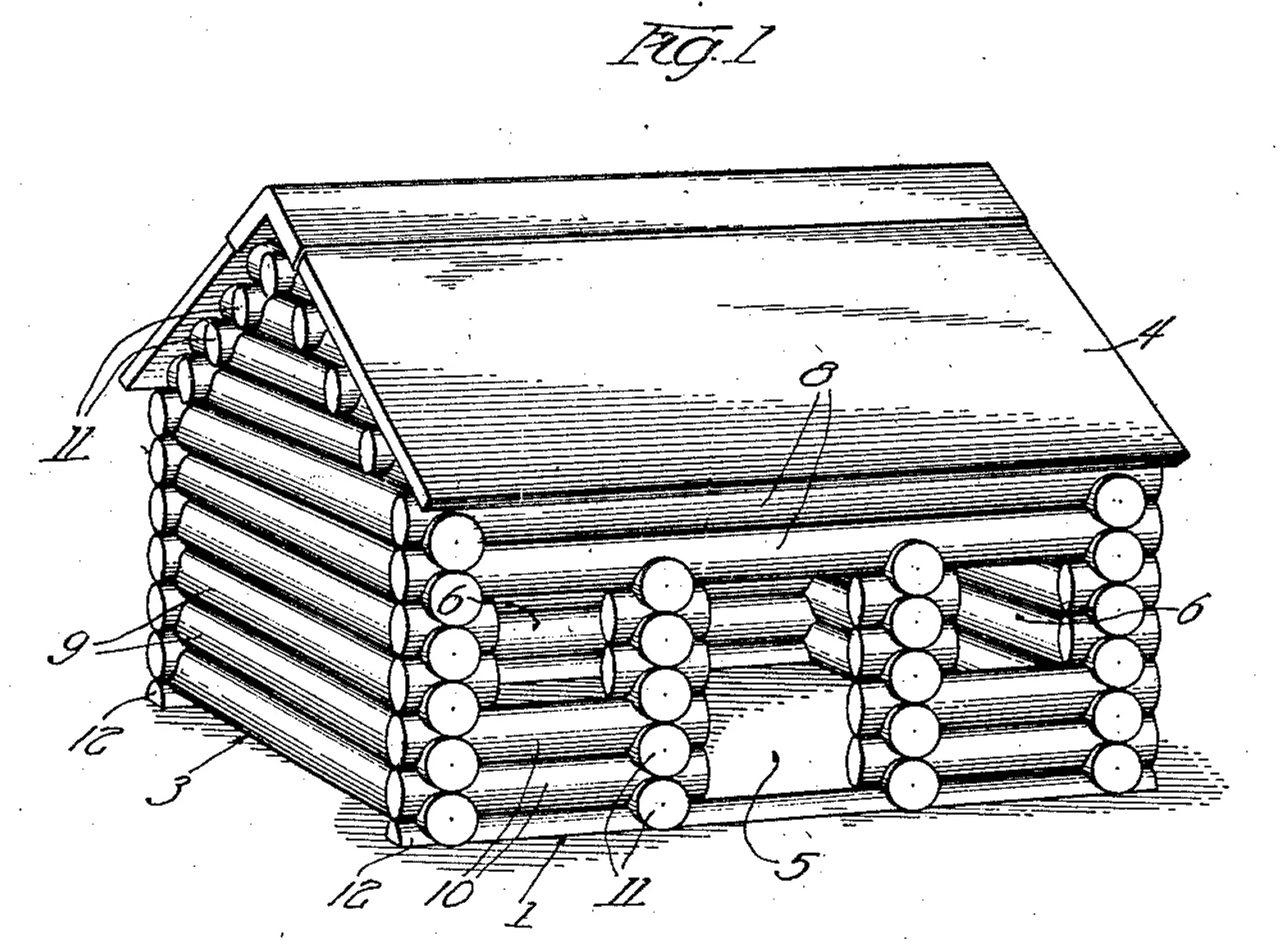

A patent drawing for Lincoln Logs via Wiki Commons

6. His son created Lincoln Logs

Frank Lloyd Wright was actually born Frank Lincoln Wright, his middle name a nod to Abraham Lincoln. But he later changed his name to honor his mother’s family, the Lloyd Joneses originally from Wales. He named his second-eldest son, born in 1892, John Lloyd Wright, but they became estranged before John had even turned 18. When John himself became an architect, they reunited, but once quickly fell out again over a discrepancy about John’s salary when they were working together on the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. Though this project led him to be without an architectural practice, it did lead to his most famous work.

One of the best-known facts about the Imperial Hotel is that FLW designed it to be earthquake-proof (in fact, it withstood the 1923 Great Tokyo Earthquake). To realize this, he set the wooden foundation beams in an interlocking pattern, a construction technique that caught the eye of his toy-loving son. After returning to Chicago, John self-financed his Red Square Toy Company, so named after the symbol that had become associated with his father. In 1918, he brought his first toy to the market–notched miniature redwood logs used to build play log cabins. In 1923, he registered the name Lincoln Logs, which K’Nex, the toy’s current distributor, says is a reference to Abraham Lincoln, though many believe it’s in reference to his father.

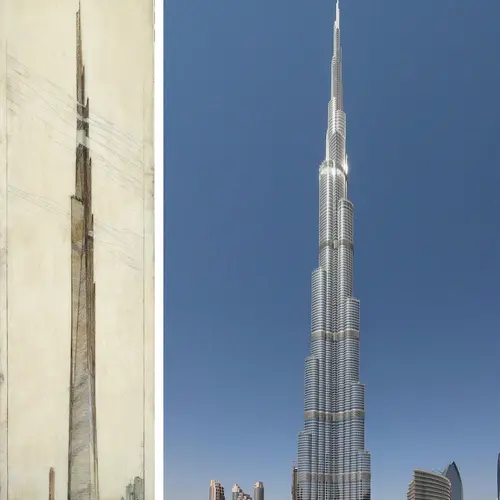

Wright’s plans for the Mile High Illinois, via The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) (L); A rendering of the Burj Khalifa via Wiki Commons (R)

Wright’s plans for the Mile High Illinois, via The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) (L); A rendering of the Burj Khalifa via Wiki Commons (R)

7. He tried to build the world’s tallest structure, which inspired the world’s actual tallest building

Dubbed the Mile High Illinois, FLW’s proposal for the world’s tallest building in Chicago was detailed in his 1965 book “A Testament.” Not surprisingly, it would’ve soared a mile high, or 5,280 feet, with 582 stories and 18 million square feet. At the time, the tallest structure was the Empire State Building at less than a quarter of this height. Nevertheless, Wright envisioned that his colossus would accommodate 100,000 people, have space for 15,000 cars and 150 helicopters, and boast atomic-powered elevators with five-floor-high tandem cabs. He even went so far as to outline his idea in a 26-foot, gold ink rendering.

To give an idea of how insanely tall this is, the world’s current tallest building, Dubai’s Burj Khalifa stands at 2,717 feet. Interestingly, it’s said that the Mile High provided inspiration for the Burj, designed by architect Adrian Smith and engineer Bill Baker of the Chicago-based firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Most notably, both buildings use a tripod design; Wright’s was triangular, while the Burj has three wings. They also are both made of reinforced concrete and have a central core that rises all the way to the top, becoming a spire.

8. He wished the Guggenheim wasn’t in New York City

The Guggenheim was Wright’s first NYC Commission (and his only one still standing). He worked on the project from 1946 right up to his death. And though it’s one of the buildings most closely associated with him, he wasn’t all that excited about it, mainly because he openly hated New York. In an interview with Mike Wallace he said the skyline was nothing more than a “race for rent,” a monument to “the power of money and greed,” and completely lacking any ideas. And when Solomon R. Guggenheim commissioned him to build a space to house his vast modern art collection, Wright said, “I can think of several more desirable places in the world to build his great museum, but we will have to try New York.”

Stuck with the location, Wright took it as an opportunity to bring his organic style to the city, spending the next 16 years designing what he called a “temple of the spirit” as a new way to experience art. Interestingly, his original concept had a red marble facade–“Red is the color of Creation,” he said–and a glass elevator instead of the iconic winding staircase.

Another fun fact related to the Guggenheim–while the museum was under construction, Wright took up residence at the famed Plaza Hotel where he lived from 1954 to 1959.

9. It’s rumored that FLW was the inspiration for Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead”

Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel “The Fountainhead” was her first major literary success, centered around protagonist Howard Roark, a young architect who’s committed to designing in the modern style despite the industry’s traditional outlook. Representing the author’s belief in individualism and integrity, Roark is at least partly inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, as Rand said her character took “the pattern of his career” and his architectural ideals. She denied that Wright influenced the plot or philosophy of her novel, however, and Wright went back and forth about whether or not he believed Roark was modeled on him.

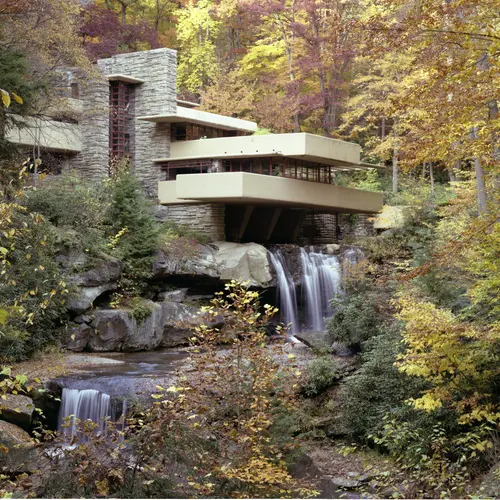

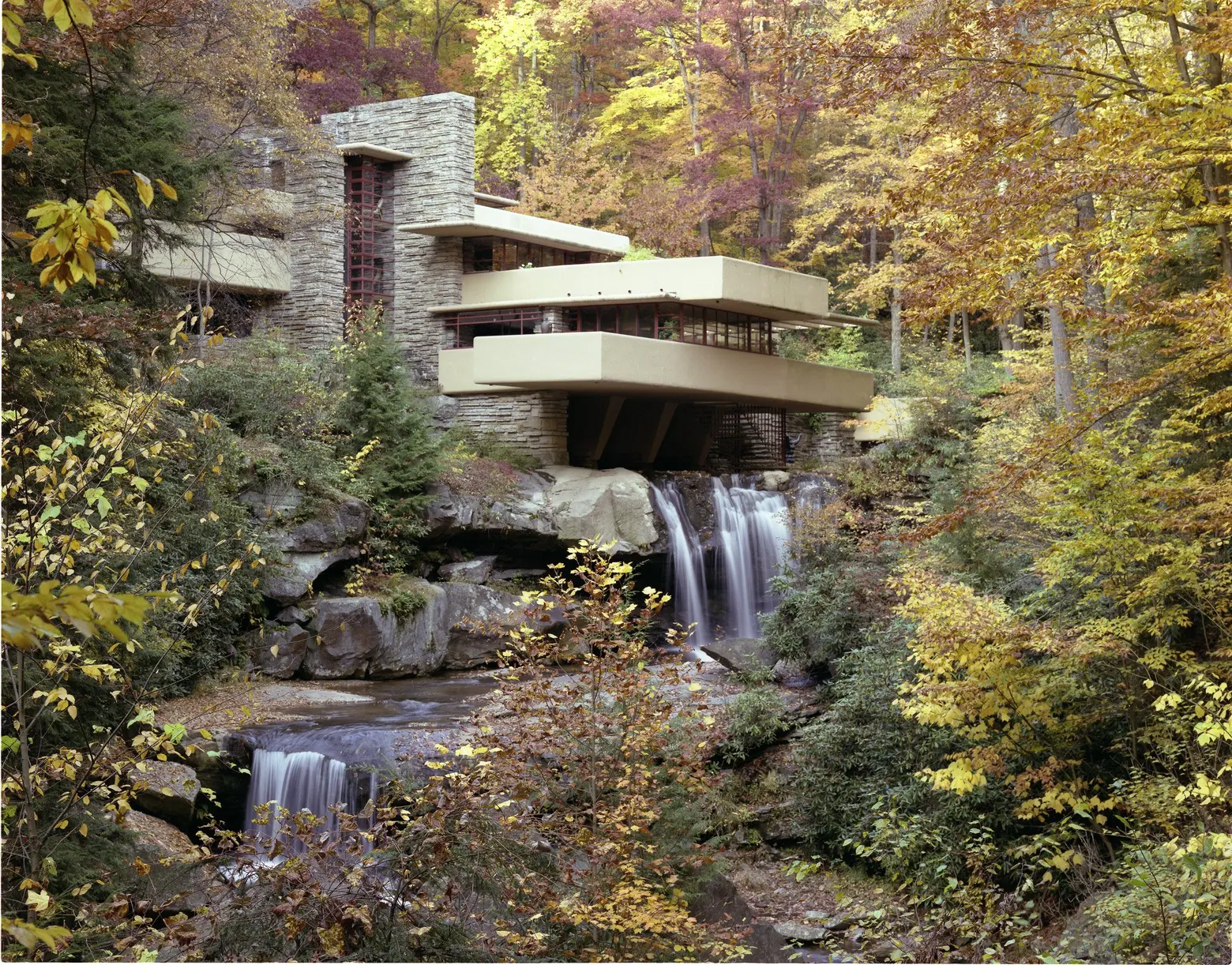

Photograph by Robert P Ruschak, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

Photograph by Robert P Ruschak, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

10. He sketched the design for Fallingwater in less than three hours

In 1935, Wright designed one of his most iconic homes–Fallingwater. Located 43 miles southeast of Pittsburgh in rural Pennsylvania, the home famously cantilevers over a 30-foot waterfall at Bear Run, one of the best examples of Wright’s skill at integrating the organic landscape into his projects. Liliane and Edgar Kaufmann (he the owner of Kaufmann’s department store) commissioned Wright to create for them a weekend retreat. They were very keen on modern art and design, and their son was even studying with the architect at the time at the Taliesin Fellowship in Wisconsin.

The home is often described as Wright’s “masterpiece,” but believe it or not it probably took him less time to design Fallingwater than any other project. The story goes that Wright first visited the Kaufmann’s property in November 1934. The following September, his client surprised him with a call that he was in Milwaukee and would be coming to visit Wisconsin to check out the plans. Despite having told them the design was underway, Wright had nothing to show. But during the two hours it took Kaufmann to drive to the studio, he and his apprentices supposedly drew the plans for Fallingwater, which ended up representing the final home with just a few small modifications.

RELATED: