10 things you never knew about Prospect Park

Image by Elizabeth Jeegin Colley for the Prospect Park Alliance

Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux debuted Prospect Park to the Brooklyn masses in 1867. Though Olmsted and Vaux had already designed Central Park, they considered this their masterpiece, and much of the pair’s innovative landscape design is still on display across all 585 acres. But it was the result of a lengthy, complicated construction process (Olmsted and Vaux weren’t even the original designers!) as well as investment and dedication from the city and local preservationists throughout the years. After challenges like demolition, neglect, and crime, the Parks Department has spent the past few decades not only maintaining the park but restoring as much of Olmsted and Vaux’s vision as possible.

It’s safe to say that these days, Prospect Park is just as impressive as when it first opened to the public. And of course, throughout its history the park has had no shortage of stories, secrets and little-known facts. 6sqft divulges the 10 things you might not have known.

The Battle of Long Island, via the Old Stone House

The Battle of Long Island, via the Old Stone House

1. The land had a long history before park construction began

The history of all that green space runs deep. The hills throughout the land were formed approximately 17,000 years ago when the receding Wisconsin Glacier, which formed Long Island, established a string of hills and kettles in the northern part of the park. (The park gets its name from the highest of those formations, Mount Prospect.) Native Americans first traveled the land, and the park’s East Drive actually follows an old Native American trail. But the forest cleared into pastures after two centuries of European colonization.

During the American Revolution, the park was the site of the Battle of Long Island. Even though George Washington’s Continental Army lost the battle, they held the British back long enough for Washington’s army to escape to Manhattan. The City of Brooklyn built a reservoir on Prospect Hill in 1856, and the sentiment to preserve the Battle Pass area was an impetus to go on and establish a large park.

2. Animals have always loved the park

Before the park was built, nearby farmers would let their animals roam freely on the land. It became so populous with animals, in fact, they had to be constantly rounded up and returned to their owners. This issue continued after the park opened. According to the David P. Colley book Prospect Park, 44 pigs, 35 goats, 18 cows, and 23 horses were impounded in 1872 alone.

3. Olmsted and Vaux were not the first to envision a park design

That honor belongs to Egbert Viele, who created the original plan for the park. According to the Bowery Boys, he wanted to retain Mount Prospect and cut a major thoroughfare through the greenery. Also, with 228 fewer acres than Olmsted and Vaux’s plan, the park would have had less landscaping and no lake, ravine or waterfalls. His proposal would have moved forward but the Civil War halted construction, giving the parks commission more time to review other designs. Olmstead and Vaux pretty much eliminated Viele’s plan entirely and were able to expand their design south and west with newly acquired land.

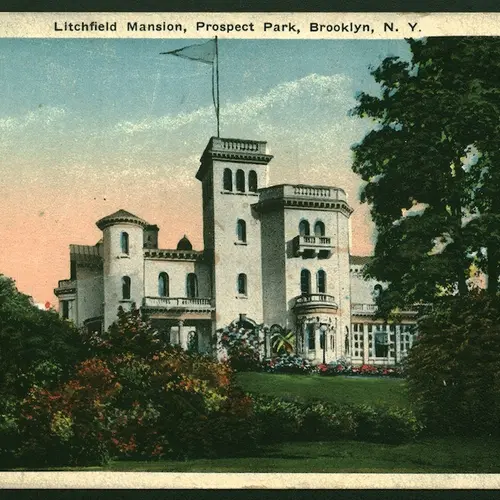

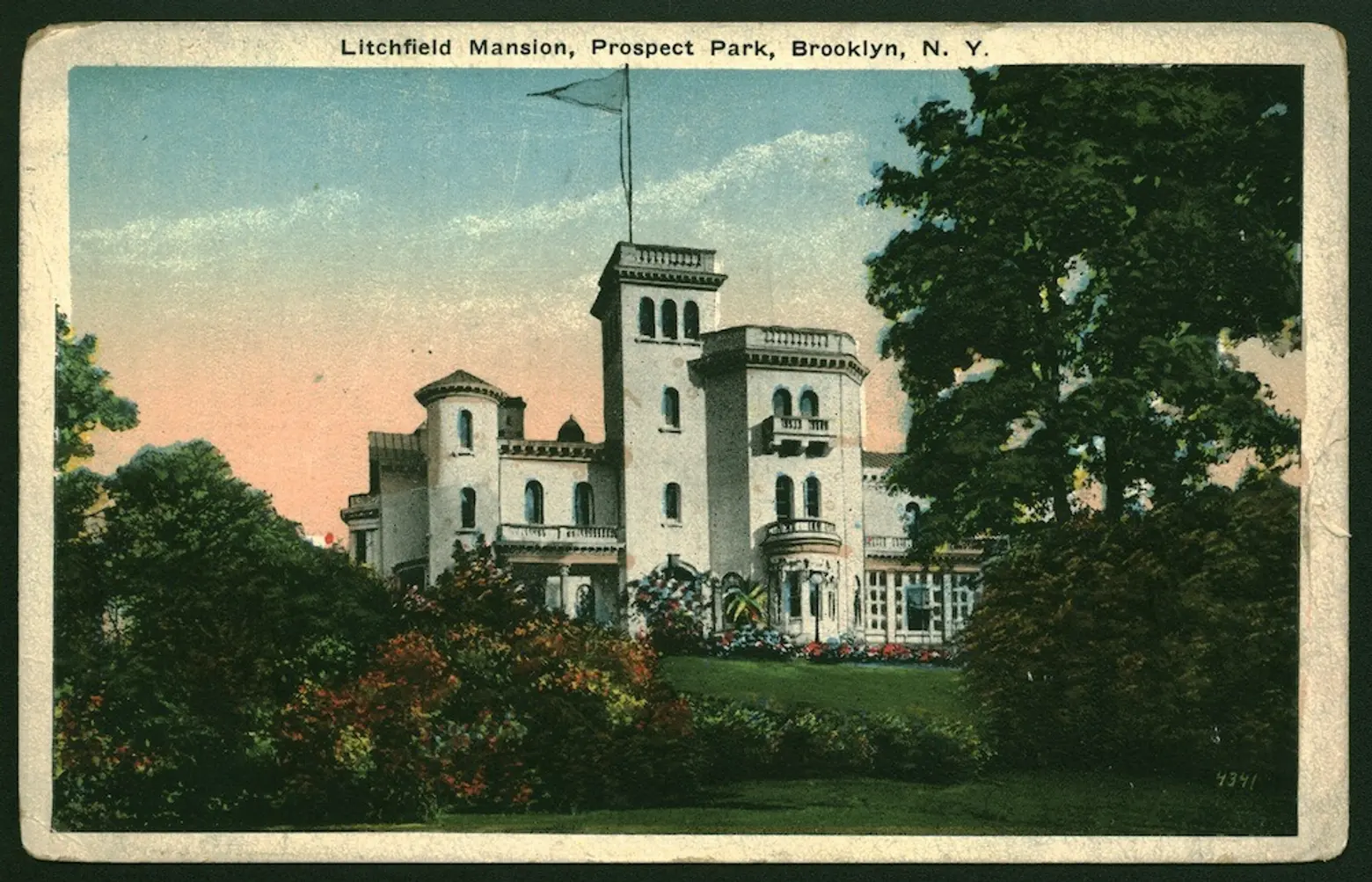

Litchfield Manor, which still stands and holds the park headquarters

Litchfield Manor, which still stands and holds the park headquarters

4. Land speculation sucked up much of the park budget

As Olmsted and Vaux moved ahead on their park proposal in 1865, real estate developers took notice. They needed more space to design what still reflects the park’s present-day layout: three distinctive regions, with a meadow in the north and west, a wooded ravine in the east and a lake in the south.

In buying up enough land to accommodate the plan, the parks commission had to deal with real estate developer Edwin Clarke Litchfield. Litchfield held the entire stretch of Ninth Avenue, which is now Prospect Park West. And in 1857 he erected his home, Litchfield Manor, on the east side of the avenue. The 1868 purchase of his holdings– the manor as well as the lots between Ninth and Tenth avenues, and from 3rd to 15th streets–cost the commission $1.7 million. That price was 42 percent of the overall expenditure for land, and the lots constitute just over five percent of the park’s acreage.

5. Vaux is responsible for the park’s most iconic structures

Frederick Law Olmstead usually gets most of the credit for designing Prospect Park, but his partner Calvert Vaux is responsible for much of the iconic building design. He was a master at incorporating buildings and structures into the landscape. He did so with the Concert Grove, planned as a formal garden with small lawns and raised flower beds, the Queen Anne-style Oriental Pavilion, the rustic shelters nestled into the landscape, and the park’s many arches and bridges.

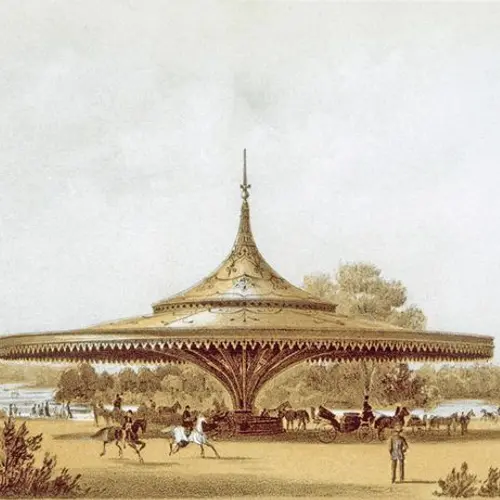

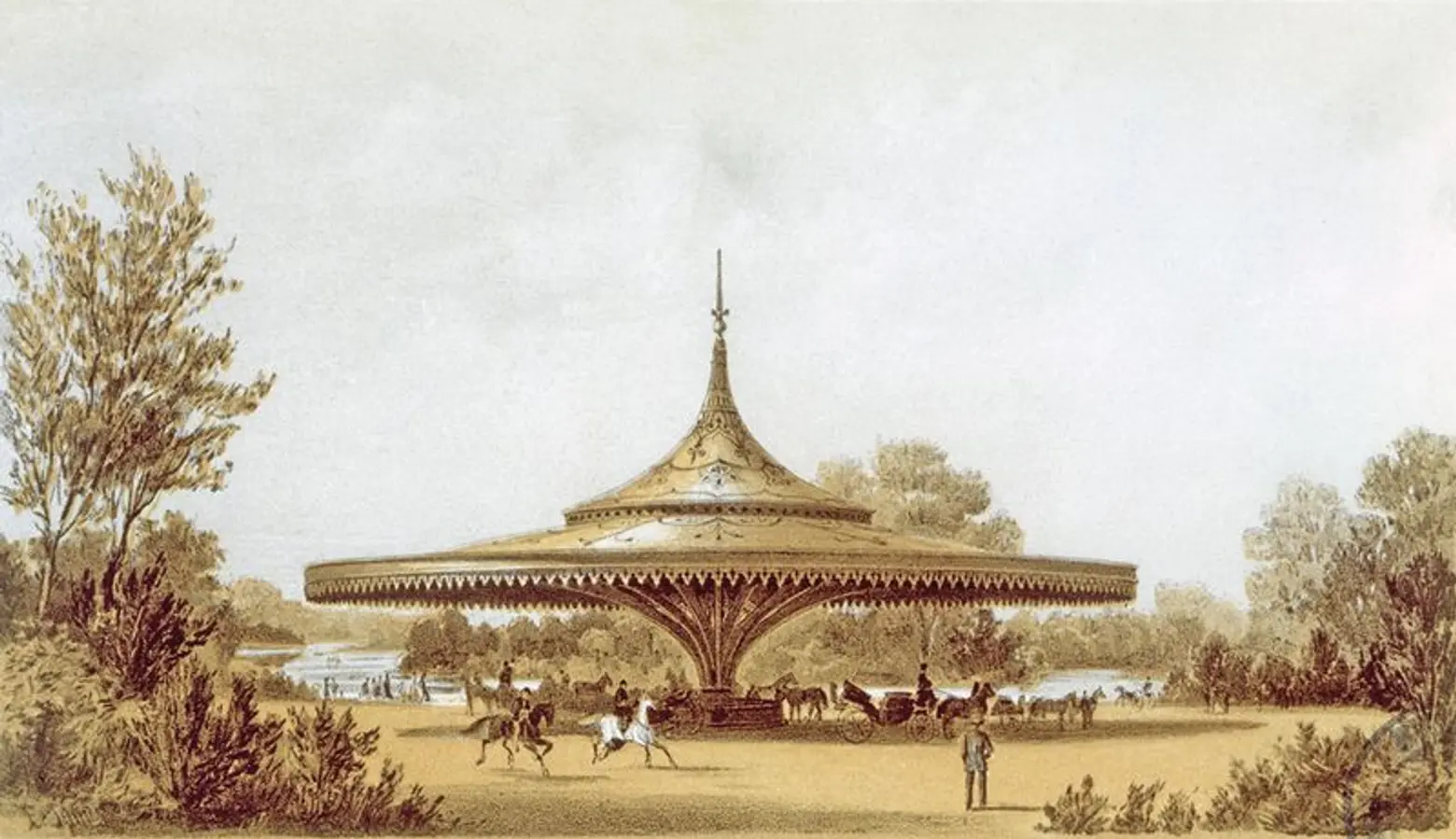

Vaux’s unbuilt design for the Carriage Concourse

Vaux’s unbuilt design for the Carriage Concourse

6. A number of proposed buildings never materialized, while others were demolished over the years

Due to the economic panic of 1873, proposals for a number of grand structures never materialized. Those include a restaurant with cascading terraces near the Concert Grove, an observation tower atop Lookout Hill, and a carriage concourse that featured a canopy, approximately 100 feet across, to provide shade for carriages and horses.

In later years, between 1930 and 1960, Robert Moses orchestrated the demolition of original Vaux structures to make way for new playgrounds, sports fields, the zoo, a bandshell and skating rink. The Dairy, which sold milk from the cows and sheep that roamed park grounds, was taken down, as well as the original Concert Grove House, the Model Yacht Club and the Greenhouse Conservatories.

The Prospect Park Boathouse, by Ben Franske for Wikipedia

The Prospect Park Boathouse, by Ben Franske for Wikipedia

7. Preservation of the park began with its iconic boathouse

For years, it was not uncommon for the city to quietly remove underutilized or redundant structures–despite their historic value–under Robert Moses’ leadership. That had happened at Prospect Park, but things began to change after the 1963 demolition of Pennsylvania Station and the resulting preservation movement. When the Parks Department proposed demolishing the Prospect Park Boathouse in 1964, local preservationists stepped up. The 1905 Boathouse was designed by protégés of McKim, Mead and White, and it shared many features with the train station. With news of its demolition, the local preservation group Friends of Prospect Park built public awareness over the park’s disappearing historical structures. By 1964, there was enough public pressure that the park commissioner halted plans for demolition.

8. The park has gone through several declines and revamps

The first time the park needed some serious TLC came near the end of the 19th century. Visitor overuse–and misuse–had left behind everything from piles of trash to broken trees. The state of the park was detailed in an 1887 report: “The grass has been worn away, the ground has become hard enough to turn water. Until this season, the soil has had constant use for 15 years, have had no rest or nourishment and but little moisture…To allow this to continue would result in killing trees and disfiguring the Park.” Thanks to the City Beautiful Movement, which took hold in the 1890s, a restoration took place with the city pouring around $100,000 into park restoration.

The park fell back into disrepair in the 1960s, when all of New York struggled from disinvestment and crime. A 1974 poll reported that 44 percent of New Yorkers “warned everyone to stay away from Prospect Park” and by 1979, only an estimated two million people visited the park per year. That began to change in the 1980s under the leadership of Tupper Thomas. By the time Tupper was ready retired in 2011, attendance at the park was pushing 10 million.

There were no straight paths designed within the park. This one winds through the ravine. By Slow Nature Fast City.

There were no straight paths designed within the park. This one winds through the ravine. By Slow Nature Fast City.

9. The park holds Brooklyn’s only forest

A 146-acre section in the center of the park, known as the Ravine, is also Brooklyn’s only forest. Olmsted and Vaux saw the Ravine as the heart of the park and were inspired by the landscape of the Adirondack Mountains. The Ravine’s stream and steep gorge is a recreation of that landscape, tucked far enough inside that you would never guess there’s a city outside. Visitors of the Ravine can wander among trees within the oldest, thickest parts of this Brooklyn forest–with everything from black oak to hickory to tulip trees.

According to the website Slow Nature Fast City, “The sandy clay of Brooklyn’s terminal glacier moraine eroded badly… Over time, silt filled and then completely buried the original waterways.” The current landscape is the result of a restoration effort that began in the 1990s and continues to this day.

The current day Lakeside Center, via Lakeside Brooklyn

The current day Lakeside Center, via Lakeside Brooklyn

10. Park restoration is still moving ahead

Efforts to return the park to Olmsted and Vaux’s grand vision are still well underway. In 2013 the city opened the LeFrak Center, a year-round skating and recreational facility. It was the final phase of a 26-acre, $74 million restoration and redesign of the park’s underutilized Lakeside section. Billed as the largest and most ambitious capital project in Prospect Park since the nineteenth century, the project added eight acres of usable space to the restored Olmsted-Vaux vision.

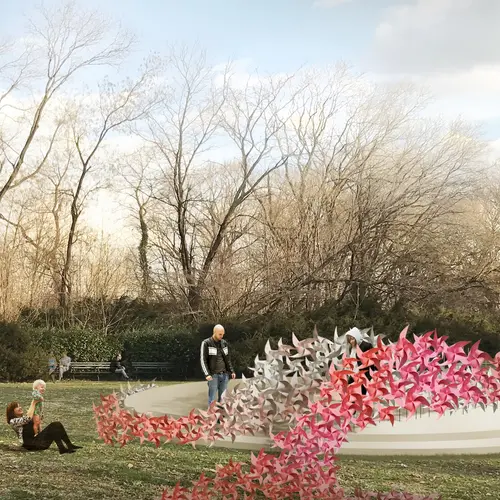

A rendering of “The Connective Project,” designed by Reddymade Design

A rendering of “The Connective Project,” designed by Reddymade Design

Most recently, the Prospect Park Alliance announced the park’s rose garden will be restored over the next few years. In the meantime, 7,000 pinwheels will be installed in the garden by Reddymade Design through the summer. The whimsical installation is in celebration of the park’s 150th anniversary

RELATED:

- VIDEO: Take an Aerial Tour of Prospect Park

- Explore Over 10,000 Acres of NYC Parkland With This Interactive Map

- See Brooklyn Before and After Gentrification in This New Photo Series

Lead image via Prospect Park Alliance