15 female trailblazers of the Village: From the first woman doctor to the ‘godmother of punk’

Greenwich Village is well known as the home to libertines in the 1920s and feminists in the 1960s and ’70s. But going back to at least the 19th century, the neighborhoods now known as Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho were home to pioneering women who defied convention and changed the course of history, from the first female candidate for President, to America’s first woman doctor, to the “mother of birth control.” This Women’s History Month, here are just a few of those trailblazing women, and the sites associated with them.

1. Bella Abzug, Feminist Icon

Bella Abzug (center) celebrating the 60th anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 1980. Via Equality Now/Flickr

Bella Abzug (center) celebrating the 60th anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 1980. Via Equality Now/Flickr

Known as “Battling Bella,” the former congresswoman (1920-1998) and leader of the Women’s movement made her home at 2 Fifth Avenue in the Village. She, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and Shirley Chisholm founded the National Women’s Political Caucus. Her first successful run for Congress in 1970 used the slogan “A Woman’s Place is in the House – the House of Representatives.” She was known as much for her ardent opposition to the Vietnam War and her support for the Equal Rights Amendment, gay rights, and the impeachment of President Nixon as for her flamboyant hats. She ran unsuccessfully for the United State Senate and Mayor of New York City.

2. Clara Lemlich, Leader of the “Uprising of the 20,000”

Two strikers on the picket line during the “Uprising of the 20,000.” Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Two strikers on the picket line during the “Uprising of the 20,000.” Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

In 1909 at the age of 23, Lemlich (1886-1982), a young garment worker who was already involved in helping to organize and lead multiple strikes and workers’ actions, led a massive walkout of 20,000 of the approximately 32,000 shirtwaist workers in New York City, in protest of deplorable working conditions and a lack of recognition of unions. The strike was almost universally successful, leading to union contracts at almost every shirtwaist manufacturer in New York City by 1910. The one exception was the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, which continued its oppressive anti-labor practices, and where a fatal fire just a year later killed 150 workers. For her radical leadership, however, Lemlich was blacklisted from the industry and pushed out by the more conservative leadership of her union. She therefore switched the focus of her advocacy to women’s suffrage and consumer protections. Lemlich lived at 278 East 3rd Street, a building which survives today, albeit in highly altered form.

3. Edie Windsor, Gay Marriage Pioneer

Edie Windsor at DC Pride in 2017, via Wiki Commons

Edie Windsor at DC Pride in 2017, via Wiki Commons

Edie Windsor (1929-2017) may have done more than any single individual to advance the cause of gay marriage in the United States. Her 2013 Supreme Court case was the first legal victory for gay marriage in the highest court in the land, striking down the ‘Defense of Marriage’ Act and forcing the federal government and individual states to recognize same-sex marriages legally performed in other U.S. states and countries. This led directly to the 2015 Supreme Court decision recognizing gay marriage nationally. Windsor had sued to have the federal government recognize her marriage to longtime partner Thea Speyer, which had been legally performed in Canada. Windsor met Speyer at Portofino Restaurant at 206 Thompson Street in Greenwich Village in 1963. In the 1950s and ’60s, Portofino was a popular meeting place and hangout for lesbians. Speyer and Windsor lived at 2 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village until their respective deaths in 2009 and 2017.

4. Emma Goldman, “The Most Dangerous Woman in America”

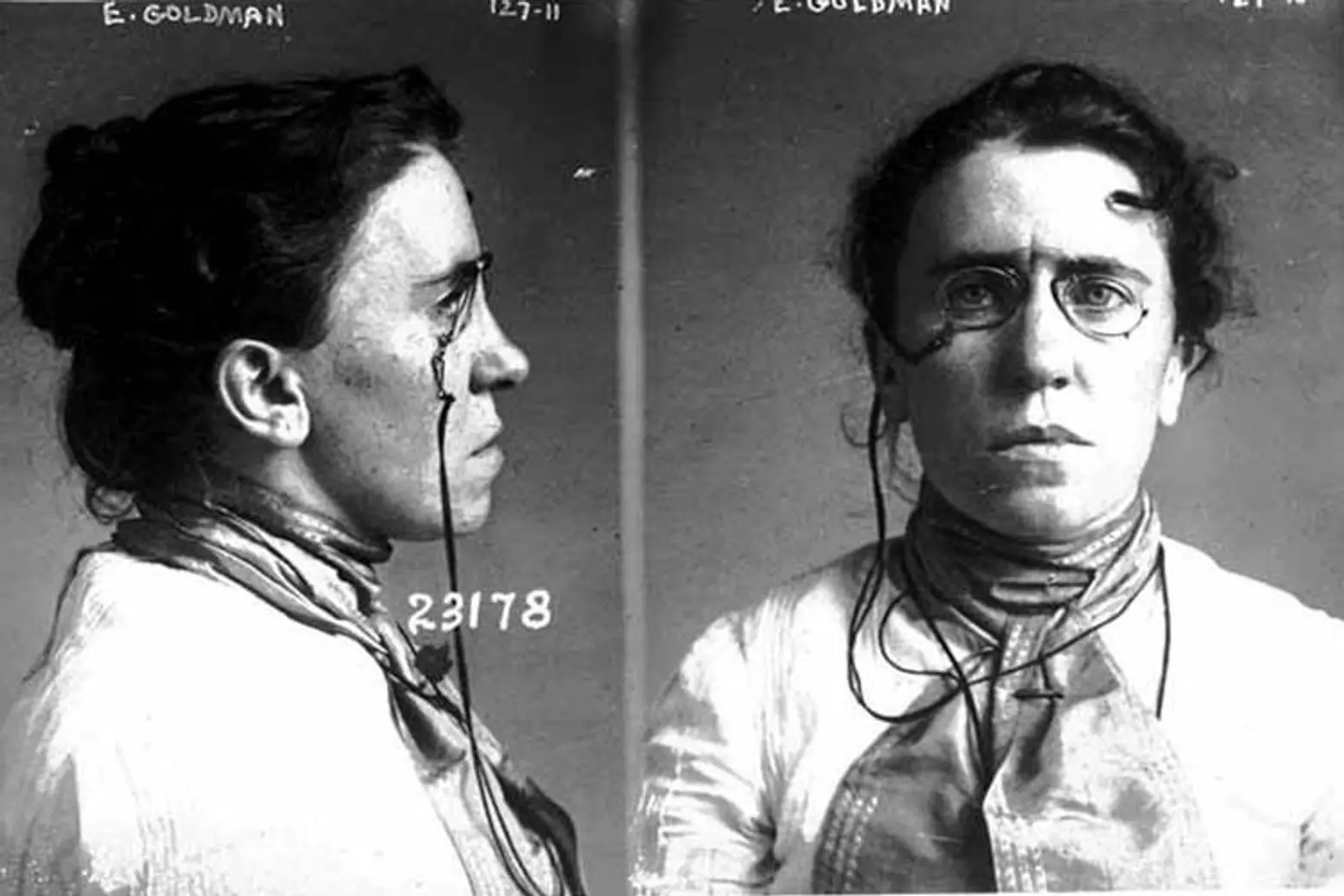

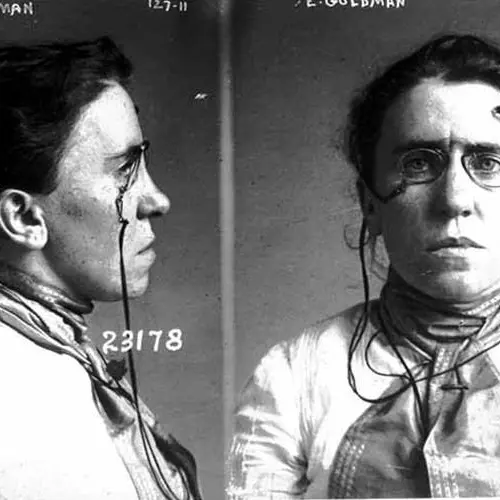

Emma Goldman’s 1901 mugshot in Chicago after being arrested on suspicion of involvement with the assassination of US President William McKinley, via Wiki Commons

Emma Goldman’s 1901 mugshot in Chicago after being arrested on suspicion of involvement with the assassination of US President William McKinley, via Wiki Commons

So named for her radical activities, Emma Goldman (1869-1940) lived at 208 East 13th Street, a tenement which still stands today. Goldman was an anarchist, political activist, and writer who supported a wide range of controversial causes, including free love, birth control, women’s equality, union organization, and workers’ rights. She was arrested multiple times for incitement to riot, distributing information on birth control, incitement to not register for the draft and sedition.

In 1889 Goldman left Rochester (and a husband) for New York City, where she met prominent anarchists Johann Most and Alexander Berkman. Goldman and Berkman would form a lifelong relationship, as both friends and lovers. In 1903, she moved into 208 East 13th Street, where she published a monthly periodical, Mother Earth, that served as a forum of anarchist ideas and a venue for radical artists and writers. The Mother Earth magazine hosted a Masquerade Ball at Webster Hall in 1906, which was broken up by the police. In 1919, she was deported to Russia with approximately 250 other alien radicals. Initially a supporter of the Russian Revolution, she eventually became a fierce critic of the repressive practices of the Soviet regime. Living in England and France, she fought in the Spanish Civil War and died in Canada.

5. Emma Lazarus, Author of “The New Colossus”

Emma Lazarus via Wiki Commons (L); a plaque outside her former home at 18 West 10th Street via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

Emma Lazarus via Wiki Commons (L); a plaque outside her former home at 18 West 10th Street via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

Lazarus (1849-1887) lived at 18 West 10th Street in Greenwich Village. Born into a successful family, she became an advocate for poor Jewish refugees and helped establish the Hebrew Technical Institute of New York to provide vocational training for destitute Jewish immigrants. As a result of anti-Semitic violence in Russia following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, many Jews emigrated to New York, leading Lazarus, a descendant of German Jews, to write extensively on the subject.

In 1883 she wrote her best-known work, the poem “The New Colossus,” to raise funds for the construction of the Statue of Liberty. In 1903, more than fifteen years after her death, a drive spearheaded by friends of Lazarus succeeded in getting a bronze plaque of the poem, now so strongly associated with the monument, placed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. It includes the famous lines: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

6. Margaret Sanger, the Mother of Modern Birth Control

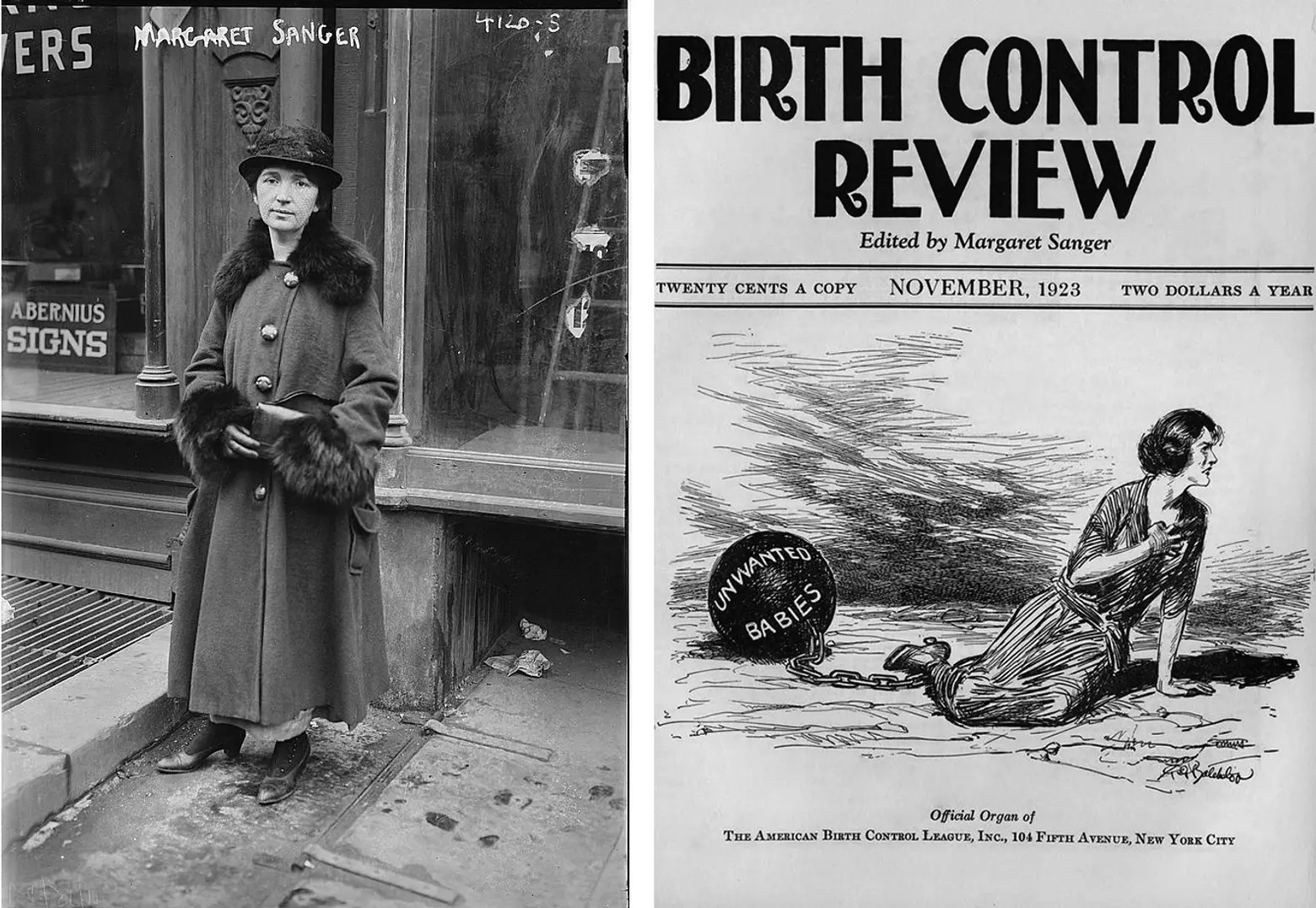

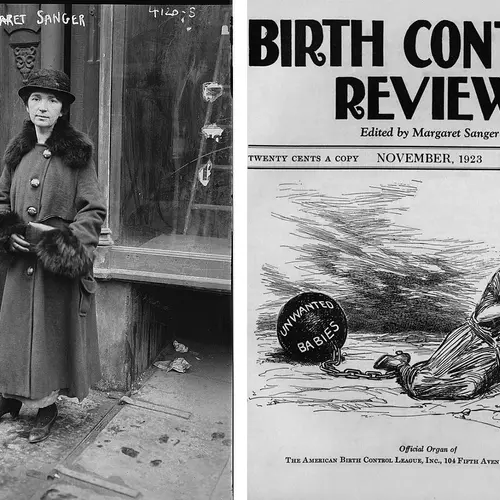

Margaret Sanger in 1917 outside her Brownsville clinic via Wiki Commons (L); A 1923 cover of Sanger’s “Birth Control Review” via Peter K. Levy/Flickr (R)

Margaret Sanger in 1917 outside her Brownsville clinic via Wiki Commons (L); A 1923 cover of Sanger’s “Birth Control Review” via Peter K. Levy/Flickr (R)

Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) was a family planning activist who is credited with popularizing the term “birth control,” a sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger began working as a visiting nurse in the slums of the East Side. One of 11 children, she helped deliver several of her siblings and saw her mother die at 40, in part from the strain of childbirth. She became a vocal proponent of birth control, which was illegal in the United States. She opened the first birth control clinic in the United States in Brooklyn, for which she was arrested, though her court cases on this and other charges led to the loosening of laws around birth control. One of the clinics she ran was located at 17 West 16th Street, just north of Greenwich Village, and she lived at 346 West 14th Street and 39 5th Avenue in Greenwich Village. Sanger established the organizations that evolved into today’s Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

7. Victoria Woodhull, First Female Candidate for President of the United States

An 1871 illustration in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of Victoria Woodhull arguing for the right to vote, the first woman to testify before a House committee. Courtesy of the Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives.

An 1871 illustration in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of Victoria Woodhull arguing for the right to vote, the first woman to testify before a House committee. Courtesy of the Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Victoria Woodhull (1838-1927) was a women’s rights activist who advocated for being able to freely love who you choose, and the freedom to marry, divorce, and bear children without government interference. She and her sister Tennessee were the first women to found a stock brokerage firm on Wall Street, and a newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, which began publication in 1870. In the early 1870s, Woodhull became politically active, speaking out for women’s suffrage. She argued that women already had the right to vote since the 14th and 15th Amendments guaranteed the protection of that right for all citizens and that all they had to do was use it. She earned the support of women’s rights activists such as Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Isabella Beecher Hooker.

On April 2, 1870, Woodhull announced her candidacy for President by writing a letter to the editor of the New York Herald. She was nominated under the newly formed Equal Rights Party in 1872 after speaking publicly against the government being composed only of men. This made her the first woman to ever be nominated for president. The party also nominated abolitionist Frederick Douglass for Vice President. The Equal Rights Party hoped to use the nominations to reunite suffragists with African-American civil rights activists. Woodhull was vilified in the press for her support of free love, and she was arrested on charges of “publishing an obscene newspaper” after she devoted an issue of her newspaper to highlighting the sexual double standard between men and women. Woodhull lived in a house at 17 Great Jones Street, which was demolished along with neighboring houses when Lafayette Street was extended through the area at the turn of the 20th century.

8. Elizabeth Jennings Graham, Streetcar Desegregation Crusader

The corner of Pearl and Chatham streets, where Jennings hailed the bus. Photo via New York Historical Society

The corner of Pearl and Chatham streets, where Jennings hailed the bus. Photo via New York Historical Society

A century before Rosa Parks, Elizabeth Jennings Graham (1827-1901) stood up for and helped win the right of African-Americans to ride on New York City’s streetcars. On her way to play the organ at the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church at 228 East 6th Street (west of 2nd Avenue, since demolished) in July 1854, Graham was forcibly removed by a conductor and policeman from the Third Avenue Streetcar after she refused to leave voluntarily. At the time, New York streetcars traditionally did not allow African-Americans to ride on their fleet.

Graham wrote a letter about the experience, in which she was treated quite roughly, published in the New York Tribune by Frederick Douglass and Horace Greeley. The incident sparked widespread outrage and protest by New York’s African-American community, and Graham sued the company, conductor, and driver. She was represented in her case by a young lawyer named Chester A. Arthur, who would become the 21st President of the United States more than 30 years later. The court ruled in her favor, awarding her damages and finding that the rail line had no basis to prohibit persons of color from riding their streetcars if they were “sober, well behaved, and free from disease.” While the ruling did not prohibit future discrimination in public transportation, it did provide an important precedent and rallying point for New York’s African-American community in its ongoing struggle for equality.

9, 10, 11, 12, 13. Mae West, Ethel Rosenberg, Valerie Solanas, Angela Davis, and Dorothy Day

A 1938 photo showing the Women’s House of Detention south of the Jefferson Market Courthouse, via NYPL

A 1938 photo showing the Women’s House of Detention south of the Jefferson Market Courthouse, via NYPL

What do these women have in common? All were jailed in the notorious Women’s House of Detention, or its predecessor, the Jefferson Market Prison, both located on the site of the present-day Jefferson Market Garden on Greenwich Avenue and 10th Street. In 1927, Mae West was jailed in the Jefferson Market Prison after being arrested on obscenity charges for her performance in her Broadway play “Sex” (just five years earlier, West got her big break in Greenwich Village with a starring role in the play “The Ginger Box” at the since-demolished Greenwich Village Theater on Sheridan Square). Not long after West’s internment at the Jefferson Market Prison, the jailhouse was demolished to make way for the supposedly more humane, Art Deco-style and WPA-mural adorned Women’s House of Detention.

Ethel Rosenberg was held in the Women’s House of Detention in the early 1950s during her trial for espionage and before her execution (Rosenberg also lived at 103 Avenue A in the East Village, which still stands, and her memorial service was held at the Sigmund Schwartz Gramercy Park Chapel at 152 Second Avenue, which has been demolished). Dorothy Day was held there in 1957 for refusing to participate in a mandatory nuclear attack drill in 1957 (Day also established two locations for her Catholic Worker in the East Village at 34-36 East 1st Street and 55 East 3rd Street, both of which still stand). Valerie Solanas, author of the S.C.U.M. (Society for Cutting Up Men) Manifesto was held here in 1968 after shooting Andy Warhol (Solanas was known to sleep on the streets of Greenwich Village and the East Village, to sell copies of the SCUM Manifesto on the streets of Greenwich Village, and by some accounts lived for a time at a flophouse on West 8th Street, now the upscale Marlton Hotel). In 1970, Black Panther Angela Davis, then on the F.B.I’s Ten Most Wanted fugitives list, was held here after her arrest in a Midtown hotel following claims she aided in the murder and kidnapping of a judge in California. Davis was no stranger to Greenwich Village, having attended the Little Red Schoolhouse just a half-dozen blocks to the south of the prison. The Women’s House of Detention was demolished in 1974.

14. Elizabeth Blackwell, the First Woman Doctor in America

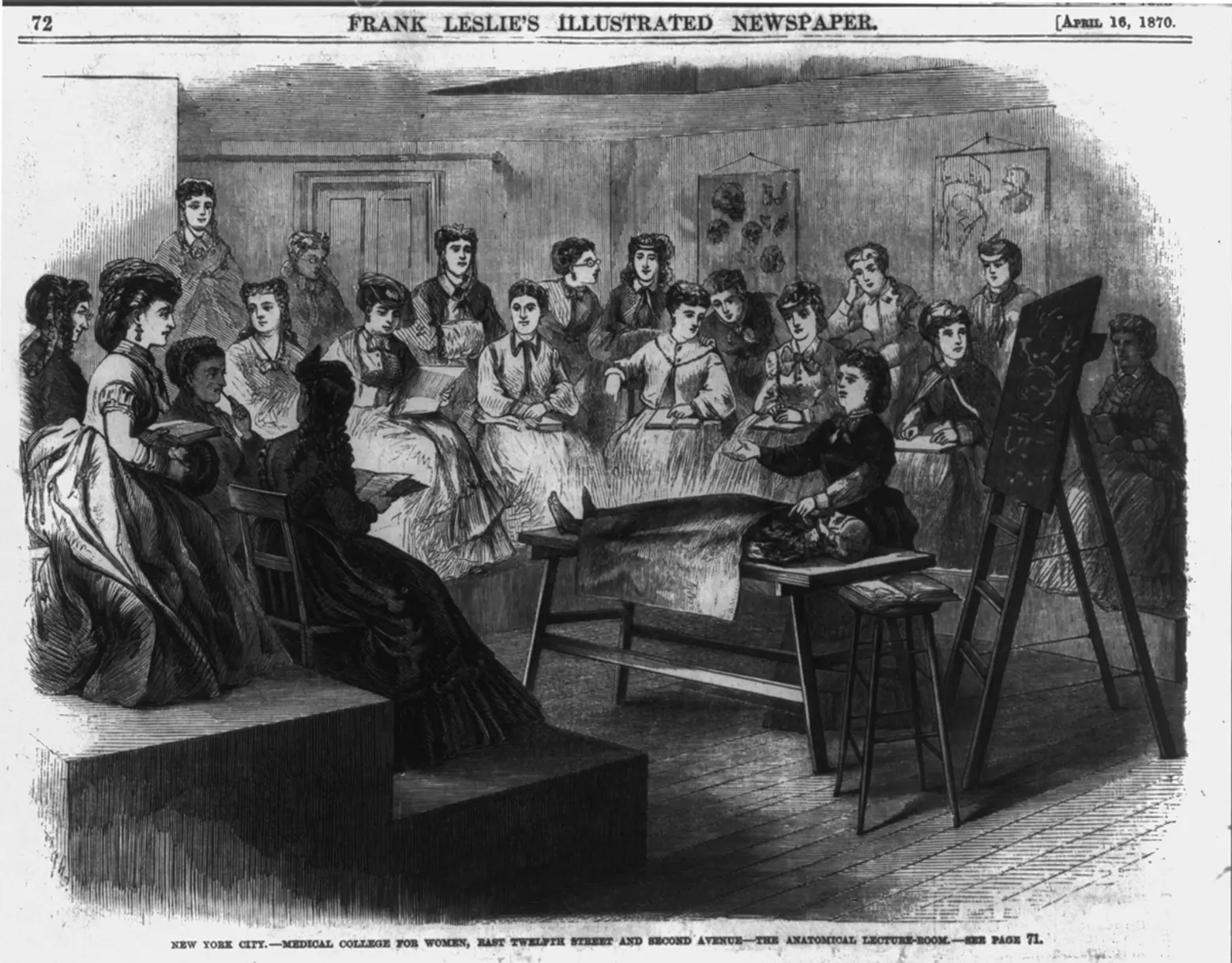

An 1870 newspaper illustration of Elizabeth Blackwell giving an anatomy lecture alongside a corpse at the Woman’s Medical College of New York Infirmary. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

An 1870 newspaper illustration of Elizabeth Blackwell giving an anatomy lecture alongside a corpse at the Woman’s Medical College of New York Infirmary. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Blackwell (1821-1910) was born in England and received her medical degree, the first for a woman in America, in upstate New York in 1849. But it was in Greenwich Village and the East Village that she blazed new trails for women and medicine. She arrived in New York City in 1851 after being denied work and the ability to practice medicine because of her gender. She rented a floor in the still extant but highly altered building at 80 University Place, where she both lived and practiced medicine, in spite of the ridicule and objections of her landlady and neighbors. In 1854 Blackwell opened the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children in a house which still stands at 58 Bleecker Street, providing much-needed services to a destitute and underserved population, and the only place where women could seek medical care from a female doctor. In 1868 Blackwell established the first women’s medical school and hospital in America at 128 2nd Avenue, providing training to aspiring female physicians and care to women in need. The college educated more than 350 female physicians.

15. Patti Smith, Godmother of Punk

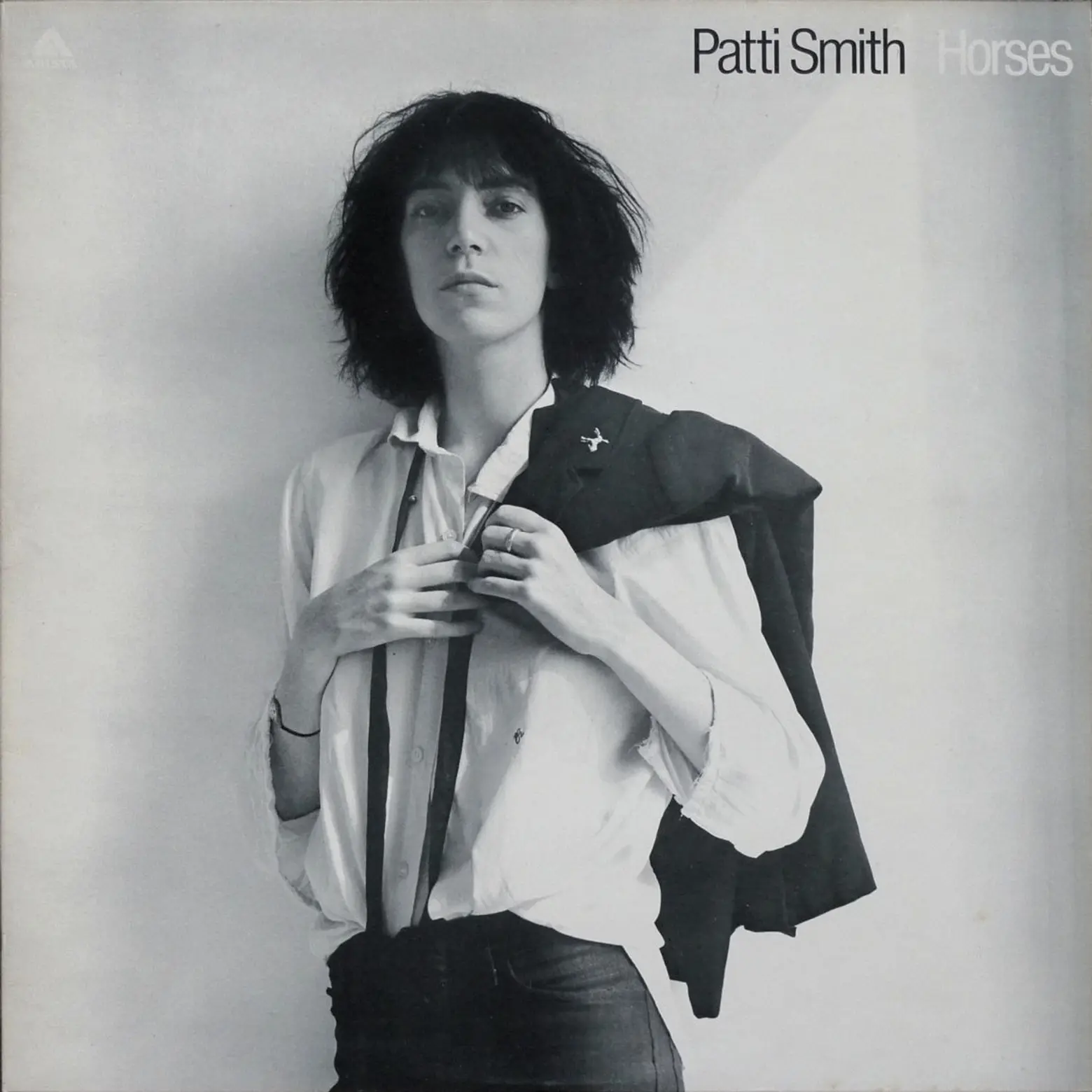

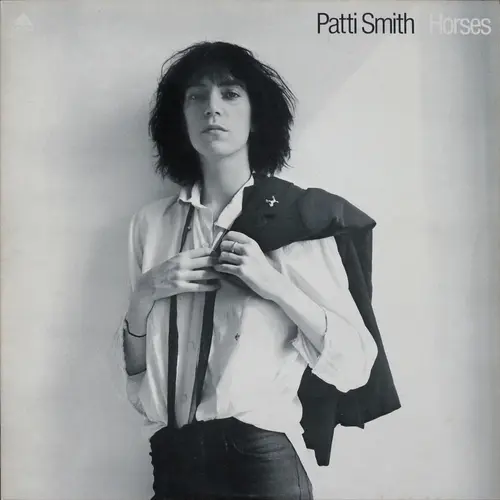

The “Horses” album cover, via John Keogh/Flickr

The “Horses” album cover, via John Keogh/Flickr

Smith (b. 1946) transformed American music with her debut album “Horses” in 1975. Opening with the line “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine,” the record fused elements of nascent punk rock and beat poetry. Smith would go on to be considered one of the most influential rock musicians of all time, and would work with Bob Dylan, John Cale, and Bruce Springsteen, among many others. Smith came to New York in 1967 from New Jersey, spending much of her time in Lower Manhattan. She recorded “Horses” at Electric Lady Studios on West 8th Street, performed poetry at St. Mark’s in the Bowery Church, met her lover and lifelong friend Robert Mapplethorpe in Tompkins Square, was photographed by Mapplethorpe (whose iconic image of Smith on the cover of “Horses” helped catapult her to fame) in his studio at 24 Bond Street, and had early residencies at CBGB’s on the Bowery and the Bitter End on Bleecker Street which helped launch her career. Smith continues to live in Greenwich Village today.

To find out about more sites associated with women’s history in Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo, see GVSHP’s Civil Rights and Social Justice Map.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED:

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Jane Jacobs should be added to this list. The Village as it is today wouldn’t exist with out her.