15 Underground Railroad stops in New York City

Photo of Harriet Tubman statue in Harlem via denisbin on Flickr

For over 200 years, most of New York City favored slavery because the region’s cotton and sugar industries depended on slave labor. During the colonial era, 41 percent of NYC’s households had slaves, compared to just six percent in Philadelphia and two percent in Boston. Eventually, after the state abolished slavery in 1827, the city became a hotbed of anti-slavery activism and a critical participant in the Underground Railroad, the network of secret churches, safe houses, and tunnels that helped fugitive slaves from the south reach freedom. While some of these Underground Railroad sites no longer exist or have relocated, a few of the original structures can be visited today, including Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church and the Staten Island home of staunch abolitionist Dr. Samuel Mackenzie Elliott. Ahead, travel along the Underground Railroad with 15 known stops in New York City.

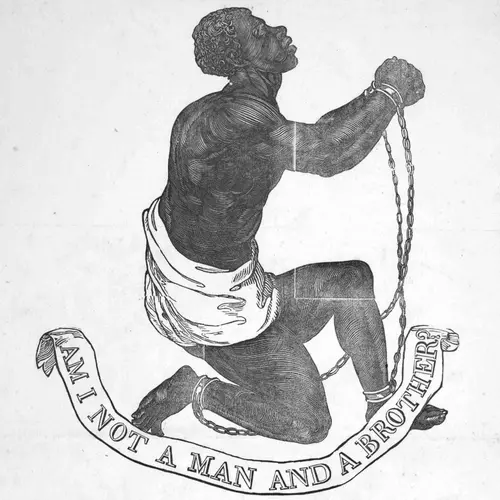

“American Anti-Slavery Society, American Anti-Slavery Almanac, for 1839” (New York: S. W. Benedict, 1839), 19. Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

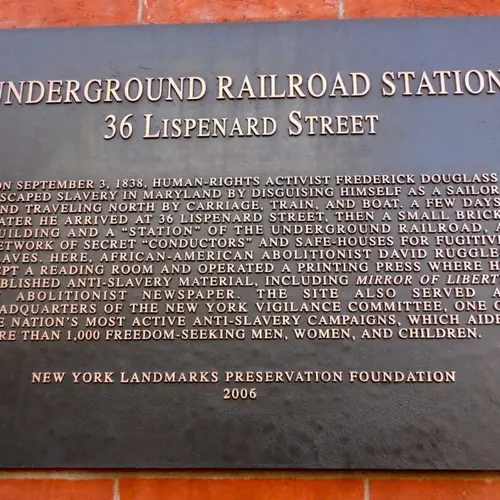

1. David Ruggles Boarding Home

36 Lispenard Street, Soho, Manhattan

After arriving in New York from Connecticut at the age of 17, David Ruggles quickly became one of the most important anti-slavery activists in the country. In 1835, Ruggles helped found the New York Committee of Vigilance, an integrated group focused on protecting runaways and confronting slave catchers, called “blackbirders.” Ruggles is said to personally have helped as many as 600 fugitives, including Frederick Douglass, by sheltering them at his home on Lispenard Street. In his autobiography, Douglass wrote, “I had been in New York but a few days, when Mr. Ruggles sought me out, and very kindly took me to his boarding-house at the corner of Church and Lespenard Streets.”

Ruggles also ran a bookstore and library out of his home, distributing anti-slavery pamphlets and other reading materials. His original three-story townhouse was demolished and a La Colombe Coffee shop now sits at the same location, with a plaque honoring Ruggles and his efforts.

Photo by Beyond My Ken on Wikimedia

2. Rev. Theodore Wright House

2 White Street, Tribeca, Manhattan

Theodore Wright, the first African American to attend a theological seminary in the U.S., was an active abolitionist and minister in New York City. In 1833, he became one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society as well as the Vigilance Committee. Wright’s Tribeca home became a stop on the Underground Railroad. While there are few documents preserved, it is believed that Wright helped 28 men, women, and children by bringing them food and a way to get to Albany. His original Dutch-style house located at 2 White Street still exists, preserved as a New York City landmark.

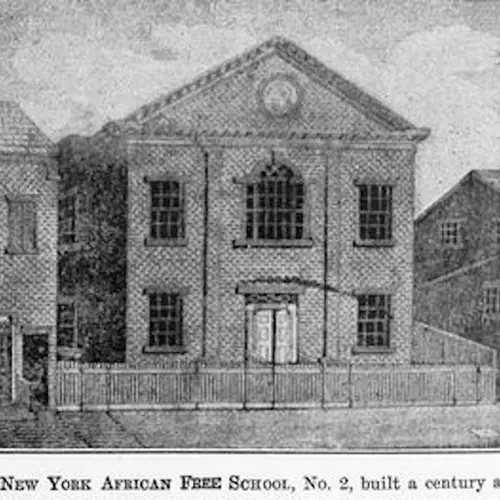

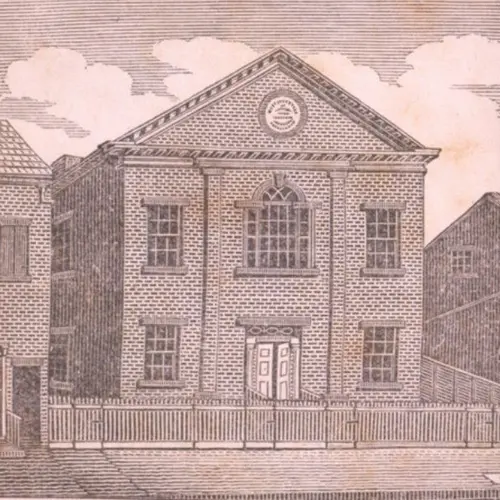

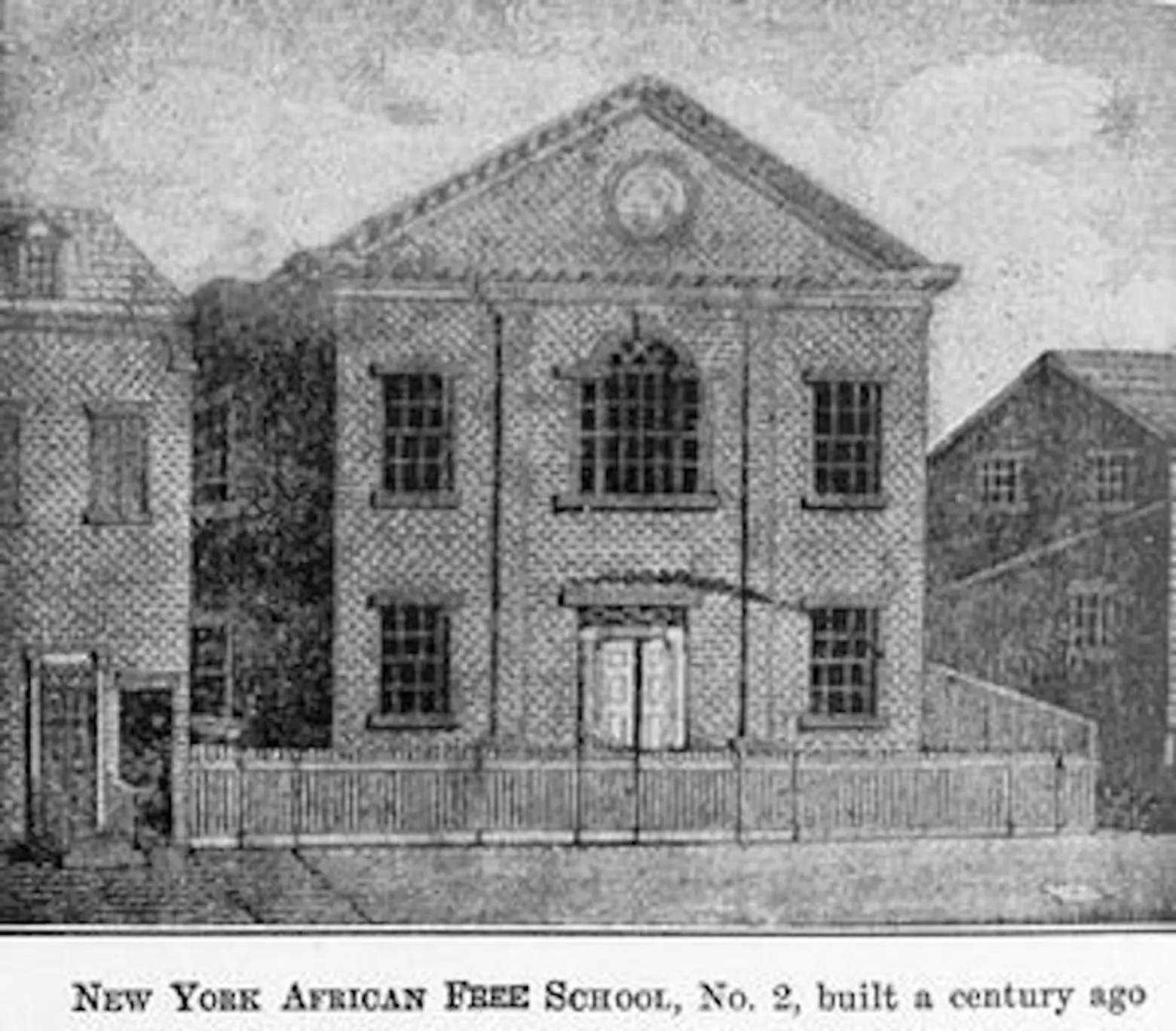

Lithograph of second school, 1922, after an 1830 engraving from a drawing by student Patrick H. Reason; Via Wikimedia

3. African Free Schools

135-137 Mulberry Street, Chinatown, Manhattan

Founded by the pro-abolition New York Manumission Society in 1787 by Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, the African Free School educated children of slaves and free people of color. The schools, which grew to enroll 1,400 students in seven buildings, eventually became a part of the city’s public schools in 1834. In addition to educating black children, the school located on Mulberry Street served as a purported stop on the Underground Railroad.

Streetview of 42 Baxter Street; © 2023 Google

4. African Society for Mutual Relief

42 Baxter Street, Chinatown, Manhattan

The African Society for Mutual Relief was founded in 1808, soon after the state made it legal for black New Yorkers to organize. During a time when everything was segregated by race, like schools and graveyards, the Society offered black people health insurance, life insurance, and even assistance for burial costs in exchange for dues. If a society member died, their family received help from the group. Located in the Five Points neighborhood, the comprehensive organization served as a school, meetinghouse, and a stop on the Underground Railroad. The building survived an anti-abolitionist riot in 1834, the Draft Riots in 1863, and multiple mob attacks. The location now serves as a state government office.

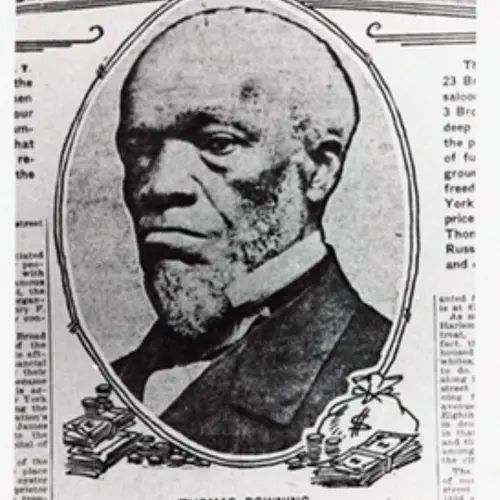

5. Downing’s Oyster House

5 Broad Street, Financial District, Manhattan

As a free man, Thomas Downing opened one of the most famous oyster houses in all of New York, Downing’s Oyster House. Located on the corner of Broad Street and Wall Street, Downing served affluential bankers, politicians, and socialites his raw, fried, and stewed oysters. While Thomas served the rich and famous upstairs, his son, George, lead escaping slaves to the basement. Between 1825 and 1860, the father-son duo helped many fugitive slaves get to Canada. Thomas also helped create the all-black United Anti-Slavery Society of the City of New York and petitioned for equal suffrage for black men. On Downing’s death on April 10, 1866, the city’s Chamber of Commerce closed to honor him.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Double ambrotype portrait of Albro Lyons, Sr. and Mary Joseph Lyons.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1860.

6. Colored Sailors’ Home

330 Pearl Street, Financial District, Manhattan

An abolitionist named William Powell opened the Colored Sailors’ Home at the corner of Gold and John Streets in lower Manhattan. Powell provided black sailors with food and shelter; the home also served as an employment center for sailors. The Sailors’ Home became a spot for anti-slavery activists to meet, as well as a place to hide fugitive slaves. Refugees from slavery were given food, shelter, and then a disguise to prepare them for their next journey. According to Leslie Harris’ book, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, Albro and Mary Lyons took over ownership of the Sailors’ Home after Powell left for Europe. Overall, Powell and the Lyons aided an estimated 1,000 fugitive slaves.

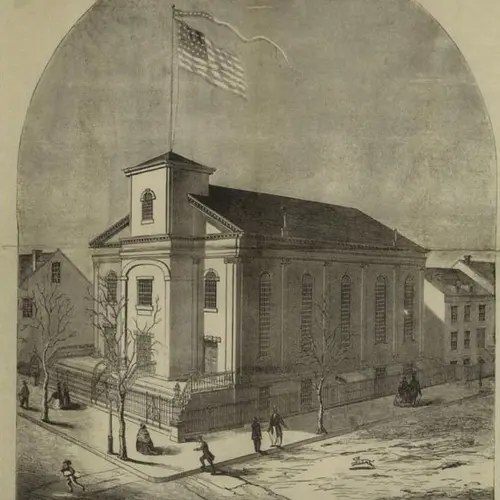

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Mother Zion, A.M.E. Zion Church” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1925-03.

7. Mother AME Zion Church

158 Church Street, Financial District, Manhattan

Opening in 1796 with a congregation of 100, Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion became the first black church in New York State. Led by Minister James Varick, the church withdrew from the segregated Methodist Episcopal Church to appeal to a growing number of anti-slavery advocates. As a stop on the Underground Railroad, the church became known as the “Freedom Church.” It helped Frederick Douglass attain freedom and Sojourner Truth was a member. After New York made slavery illegal in 1827, the church focused its attention on the nationwide abolition movement. In 1925, the church relocated to its current Harlem location at 140-7 West 137th Street.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Midsummer in the Five Points” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1873-09-13.

8. Five Points

Worth Street and Baxter Street, Chinatown, Manhattan

Five Points, a Lower Manhattan neighborhood once known for its notorious slums, was built on top of a swampy landfill. Poor newly freed slaves lived here, along with Irish and German immigrants. Interestingly, Five Points’ dwellers are credited with the creation of tap dance, an influence from both Irish and African American culture. And although it’s infamous for being riddled with crime and disease, Five Points became home to many abolitionist groups, as well as many stops along the Underground Railroad.

Now known as the St. James Presbyterian Church, Shiloh Church has relocated several times; via Wikimedia

9. The Shiloh Presbyterian Church

Frankfort Street and William Street, Financial District, Manhattan

Led by abolitionists Samuel Cornish, Theodore Wright and Henry Highland Garnet, the Shiloh Presbyterian Church became an essential stop along the Underground Railroad. Founded as the First Colored Presbyterian Church by Samuel Cornish in 1822, the congregation fought slavery together. Under Cornish’s direction, the church boycotted sugar, cotton, and rice, all products derived from slave labor. The Shiloh Church relocated several times and can be found today on West 141st Street in Harlem.

The Plymouth Church is a National Historic Landmark; photo via Wikimedia

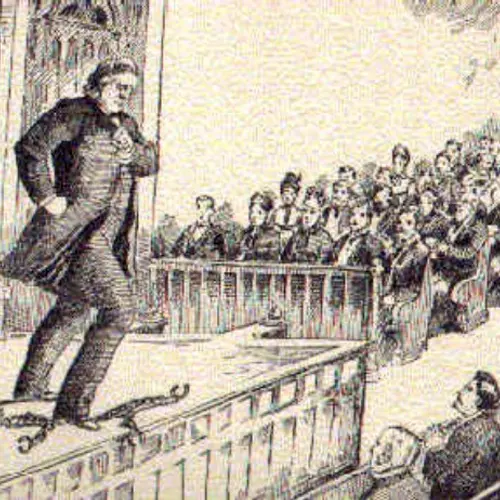

10. Plymouth Church

75 Hicks Street, Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn

While it was only founded 14 years before the start of the Civil War, Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church was known as the “Grand Central Depot” of the Underground Railroad. The first minister, Henry Ward Beecher, the brother of Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe, hid fugitive slaves in the church’s basement through tunnel-like pathways. Members of the church also provided slaves shelter in their own homes. Beecher would host mock slave auctions to demonstrate the cruelty of them and also as a way to secure their freedoms.

His most famous auction involved a 9-year-old slave, a girl named Pinky. In front of a crowd of 3,000 people, Beecher picked up a ring, put it on the girl’s finger, and said, “Remember, with this ring I do wed thee to freedom.” Plymouth Church, a National Historic Landmark within the Brooklyn Heights Historic District, remains one of the few active congregations in New York City still in its original Underground Railroad location.

11. Home of Abigail Hopper-Gibbons and James Sloan-Gibbons

339 West 29th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan

In their Chelsea rowhouse, abolitionists Abigail Hopper-Gibbons and James Sloan-Gibbons hid runaway slaves and hosted meetings for anti-slavery advocates. Abby also started a small school for African-American children in her home. As a stop on the Underground Railroad, the couple’s home helped slaves from the south reach Canada. During the Draft Riots of 1863, the Gibbons’ home was attacked because of the family’s known anti-slavery beliefs. Many black people were injured, tortured, and killed during the attacks. With some restoration, the landmarked home survived the riots, making it the only Manhattan Underground Railroad site to endure.

28 Gramercy Park; photo via Wikimedia

12. Brotherhood Synagogue

28 Gramercy Park South, Gramercy Park, Manhattan

While it first opened its doors as a Quaker Meeting House in Gramercy Park, the building now is home to the Brotherhood Synagogue. For a century, the meeting house served the 20th Street Friends. Members of the group became active in the abolitionist movement, sheltering fugitive slaves on the building’s second floor. According to the synagogue, the tunnels underneath the building remain visible and accessible today.

Photo of Elliott’s house via Wikimedia

13. Home of Dr. Samuel Mackenzie Elliot

69 Delafield Place, Staten Island

Designated a city landmark in 1967, the Staten Island home of Dr. Samuel MacKenzie Elliot’s historic significance dates back much further. Elliot, who designed the eight-room Gothic Revival-style home in 1840, became a leader of the abolitionist movement in the state. The house on Delafield Place was outfitted for slaves escaping the U.S.

Street view of 20 Verandah Place; © 2023 Google

14. Cobble Hill Carriage House

20 Verandah Place, Cobble Hill, Brooklyn

A Cobble Hill carriage house with a storied past hit the market last October for nearly $4 million. As 6sqft learned, the home at 20 Verandah Place, constructed in the 1840s, served as the home for servants and horses of wealthy homeowners. According to the current owners, the carriage house also served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

227 Duffield Street; Photo by on Wikimedia

15. Abolitionist Place

227 Duffield Street, Downtown Brooklyn

An area of Downtown Brooklyn was a known center of anti-slavery activism in New York City and the block of Duffield Street between Fulton and Willoughby was co-named “Abolitionist Place” in 2007. While not many of the original structures from the 1800s remain on the block, a two-story redbrick building at 227 Duffield stands tall to this day. Prominent abolitionists Thomas and Harriet Truesdell lived at the home and historians believe Underground Railroad stops were found in many homes along the same block. The Plymouth Church, as well as Bridge Street AWME Church, the first black church in Brooklyn, were conveniently located nearby. In 2021, the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated 227 Duffield as a New York City landmark; the city soon after bought the property to protect it from demolition.

RELATED:

- Find landmarks of the anti-slavery movement in NYC

- John Jay’s new database provides 35,000+ records of slavery in New York

- On this day in 1645, a freed slave became the first non-Native settler to own land in Greenwich Village

Editor’s note: The original version of this article was published on February 6, 2018, and has since been updated.