20 transformative women of Greenwich Village

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the designation of the Greenwich Village Historic District on April 29, 1969. One of the city’s oldest and still largest historic districts, it’s a unique treasure trove of rich history, pioneering culture, and charming architecture. GVSHP will be spending 2019 marking this anniversary with events, lectures, and new interactive online resources, including a celebration and district-wide weekend-long “Open House” starting on Saturday, April 13th in Washington Square. This is part of a series of posts about the unique qualities of the Greenwich Village Historic District marking its golden anniversary.

Few places on earth have attracted as many creative, mold-shattering, transformative women as Greenwich Village, especially the Greenwich Village Historic District which lies in its heart. From its earliest settlers in the 17th century through its bohemian heyday in the late 19th and 20th centuries right up to today, pioneering women have made the Greenwich Village Historic District their home, from congresswoman Bella Abzug and gay rights advocate Edie Windsor to playwright Lorraine Hansberry and photographer Berenice Abbott.

Via Wikimedia

1. “The Widow Marycke,” Washington Square

Too few know that the first permanent settlers of what is today Greenwich Village, and the surrounding neighborhoods of the East Village, Lower East Side, and SoHo, were former African slaves of the New Netherland colony who formed the first free black settlement in North America.

Starting in 1643, just over two dozen former slaves were granted land in an area which would come to be known as “the land of the blacks” north of the New Amsterdam settlement in the southern tip of Manhattan. Among the first half dozen of these and the first woman was a widow named ‘Marycke,’ who was granted land in what would today be the western edge of Washington Square. She and the twenty-seven other freed Africans who won land grants north of the Dutch colony had to fight off Native American raids and try to cultivate rugged, hilly, swampy land.

‘Marycke’ was not only the first independent female settler of the ‘land of the blacks’ (a second widow was granted land four years later), but was, along with four other Africans, the first settlers of what would today be called Greenwich Village, and the very first in what is today the Greenwich Village Historic District.

Via Wikimedia

2. Edna St. Vincent Millay, 75 1/2 Bedford Street

Few people are as closely associated with Greenwich Village as Millay. Perhaps that’s because the neighborhood appears right in her name – her middle name, St. Vincent, honored the hospital located on West 11th Street where her uncle’s life was saved just before she was born. The Pulitzer Prize-winning poet was known for her passionate writing and her advocacy of free love, which made her right at home in the Greenwich Village of the early 20th century. She lived in various locations throughout the Village starting in 1917, but most famously at 75 ½ Bedford Street, ‘the narrowest house in the Village’ (a location also indelibly connected to her in the popular mind, perhaps because of her poem “my candle burns at both ends”). Thought of as the embodiment of the “new woman” in the 1920s, she wrote of love for both men and women, and combined modernist and traditional forms in her poetry.

Via Wikimedia

3. Berenice Abbott, 50 Commerce Street

Abbott’s photography, especially her Depression-era, WPA-funded book Changing New York, crystalized the image of New York in the mind of much of the world as a place of dynamic but fragile beauty.

First trained as a sculptor, it was during her time in Europe as Man Ray’s assistant that she began to pursue photography. In 1929, Abbott returned to the United States and began her career-defining photo-documentation of New York City. She lived in a loft here with her partner, the noted art critic Elizabeth McCausland, from 1935 until 1965

Bella Abzug (center) celebrating the 60th anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 1980. Via Equality Now/Flickr

4. Bella Abzug, 2 Fifth Avenue

Known as “Battling Bella,” the former congresswoman (1920-1998) and leader of the Women’s movement made her home at 2 Fifth Avenue in the Village. She, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and Shirley Chisholm founded the National Women’s Political Caucus. Her first successful run for Congress in 1970 used the slogan “A Woman’s Place is in the House – the House of Representatives.” She was known as much for her ardent opposition to the Vietnam War and her support for the Equal Rights Amendment, gay rights, and the impeachment of President Nixon as for her flamboyant hats. She ran unsuccessfully for the United State Senate and Mayor of New York City.

Emma Lazarus via Wiki Commons; a plaque outside her former home at 18 West 10th Street via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

5. Emma Lazarus, 18 West 10th Street

Born into a financially successful family, Emma Lazarus became an advocate for poor Jewish refugees and helped establish the Hebrew Technical Institute of New York to provide vocational training for destitute Jewish immigrants. As a result of anti-Semitic violence in Russia following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, many Jews immigrated to New York, leading Lazarus, a descendant of German Jews, to write extensively on the subject.

In 1883 she wrote her best-known work, the poem “The New Colossus,” to raise funds for the construction of the Statue of Liberty. In 1903, more than fifteen years after her death, a drive spearheaded by friends of Lazarus succeeded in getting a bronze plaque of the poem, now so strongly associated with the monument, placed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. It includes the famous lines: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Via Wikimedia

6. Louise Bryant, 1 Patchin Place

Bryant was known as a daring and pathbreaking journalist, feminist, and political activist, who chronicled and expressed sympathy for the Russian Revolution while engaged in tumultuous relationships with fellow journalist John Reed and Eugene O’Neill. Her coverage of the Bolshevik Revolution including writings about Red leaders such as Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky was carried extensively by Hearst newspapers across the U.S. and Canada. Her coverage was collected and published in 1918 as Six Red Months in Russia, further cementing the influence she had in shaping the public’s perception and understanding of the revolutionary activities in Europe. Not content to limit herself to her writing, she embarked upon a speaking tour across the country denouncing the U.S. joining other western powers in armed intervention against the Bolsheviks, and supporting the revolution.

Byrant’s advocacy was not limited to support for the Soviet cause, however. In the United States, she was a militant suffragist, having been jailed for her activities in support of women’s right to vote. In Greenwich Village, she lived with her husband John Reed at 1 Patchin Place and became an integral part of the cultural scene which revolved around the radical publication The Masses as well as the Heterodoxy Club and the Provincetown Players.

Via Wikimedia

7. Marianne Moore, 14 St. Luke’s Place & 35 West 9th Street

Moore is considered one of the pioneers of 20th-century modernist poetry. Her early writings attracted the attention of such luminaries as Ezra Pound and T.S. Elliot, quickly catapulting her to literary prominence. In addition to publishing numerous award-winning and popular collections of poetry, she became the editor of the groundbreaking Greenwich Village literary magazine The Dial during what was considered the zenith of its influence from 1925 to 1929.

When she first moved to New York in 1918 with her mother, they settled into an apartment in a townhouse at 14 St. Luke’s Place. With success, she moved on to a comfortable apartment in a middle-class apartment building at 35 West 9th Street (both of which still stand) before eventually moving to Brooklyn – pioneering an arc which many artists and writers followed.

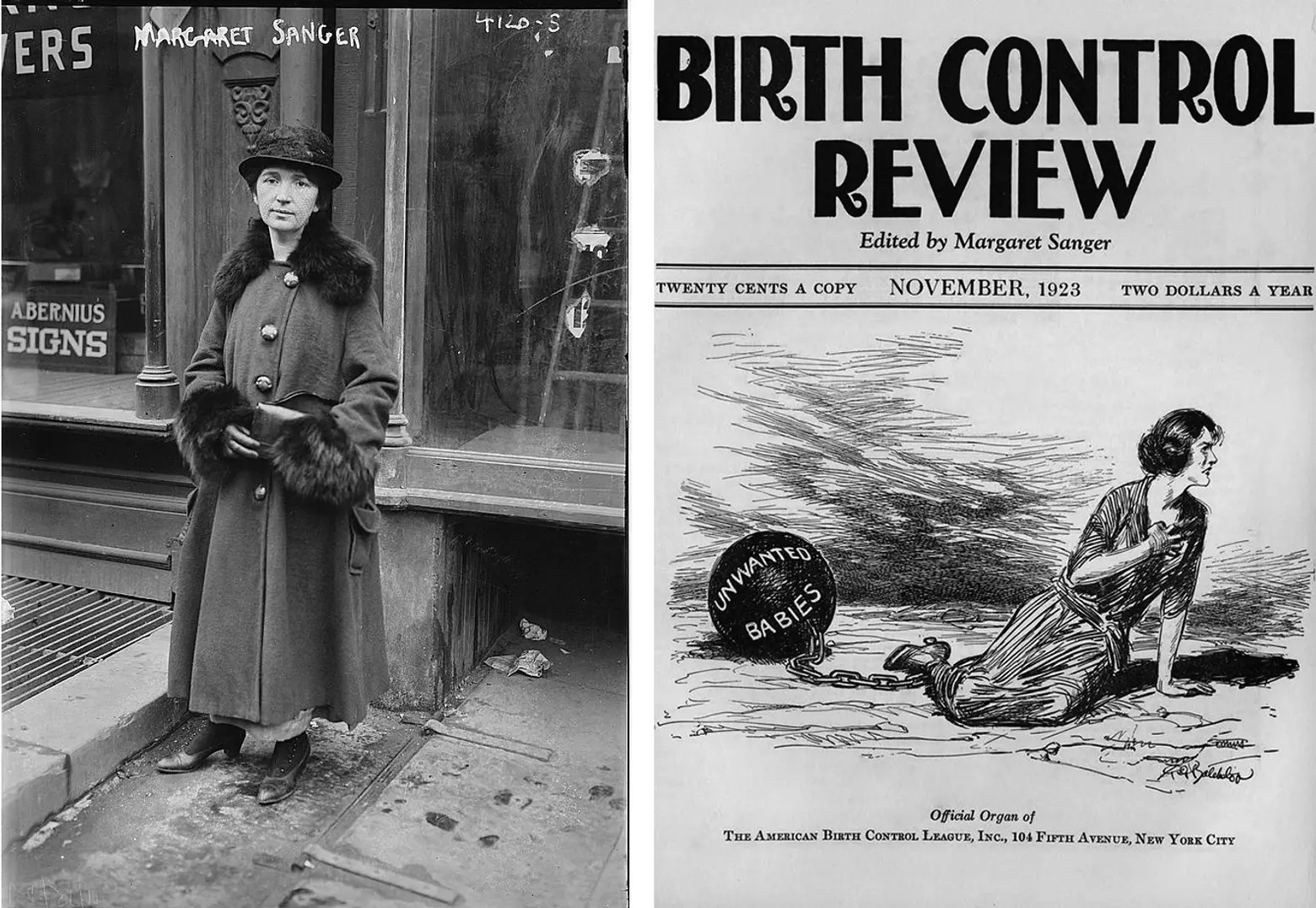

Margaret Sanger in 1917 outside her Brownsville clinic via Wiki Commons (L); A 1923 cover of Sanger’s “Birth Control Review” via Peter K. Levy/Flickr (R)

8. Margaret Sanger, 39 Fifth Avenue

Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) was a family planning activist who is credited with popularizing the term “birth control,” a sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger began working as a visiting nurse in the slums of the East Side. One of 11 children, she helped deliver several of her siblings and saw her mother die at 40, in part from the strain of childbirth. She became a vocal proponent of birth control, which was illegal in the United States. She opened the first birth control clinic in the United States in Brooklyn, for which she was arrested, though her court cases on this and other charges led to the loosening of laws around birth control. One of the clinics she ran was located at 17 West 16th Street, just north of Greenwich Village, and she lived at 346 West 14th Street and 39 5th Avenue in the Greenwich Village Historic District. Sanger established the organizations that evolved into today’s Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

Willa Cather in 1912 via Wikimedia

9. Willa Cather, 5 Bank Street & 82 Washington Place

While Cather is most noted as a chronicler of life on the American frontier, she, in fact, spent much of her life living, and writing, in Greenwich Village. Her novels My Antonia, O Pioneers!, and The Song of the Lark are considered literary classics, embedding in the public’s mind an image of the simple but challenging life on the American Great Plains.

Cather lived from 1906 until her death in 1947 in Greenwich Village. She was an editor at McClure’s Magazine where she met a proofreader named Edith Lewis with whom she would eventually share her home and life. She first lived in a since-demolished house at 60 Washington Square South (just outside the Greenwich Village Historic District, and now the site of the NYU Kimmel Center) before moving to an apartment at 82 Washington Place. From 1913 to 1927 they lived in a house at 5 Bank Street (since demolished), during which time she won the Pulitzer Prize for her World War I novel One of Ours.

A 1938 photo showing the Women’s House of Detention south of the Jefferson Market Courthouse, via NYPL

10-14. Mae West, Ethel Rosenberg, Valerie Solanas, Angela Davis & Dorothy Day, Women’s House of Detention

These five notorious women all lived, at least temporarily, in the same spot in the Greenwich Village Historic District — the notorious Women’s House of Detention, or its predecessor, the Jefferson Market Prison, both located on the site of the present-day Jefferson Market Garden at Greenwich Avenue and 10th Street.

In 1927, Mae West was jailed in the Jefferson Market Prison after being arrested on obscenity charges for her performance in her Broadway play “Sex” (just five years earlier, West got her big break in Greenwich Village with a starring role in the play “The Ginger Box” at the since-demolished Greenwich Village Theater on Sheridan Square). Not long after West’s internment at the Jefferson Market Prison, the jailhouse was demolished to make way for the supposedly more humane, Art Deco-style and WPA-mural adorned Women’s House of Detention.

Ethel Rosenberg was held in the Women’s House of Detention in the early 1950s during her trial for espionage and before her execution (Rosenberg also lived at 103 Avenue A in the East Village, which still stands, and her memorial service was held at the Sigmund Schwartz Gramercy Park Chapel at 152 Second Avenue, which has been demolished).

Dorothy Day was held there in 1957 for refusing to participate in a mandatory nuclear attack drill in 1957. Valerie Solanas, author of the S.C.U.M. (Society for Cutting Up Men) Manifesto was held here in 1968 after shooting Andy Warhol (Solanas was known to sleep on the streets of Greenwich Village, to sell copies of the SCUM Manifesto on the streets of Greenwich Village, and by some accounts lived for a time at a flophouse on West 8th Street, now the upscale Marlton Hotel).

In 1970, Black Panther Angela Davis, then on the F.B.I’s Ten Most Wanted fugitives list, was held here after her arrest in a Midtown hotel following claims she aided in the murder and kidnapping of a judge in California. Davis was no stranger to Greenwich Village, having attended the Little Red Schoolhouse just a half-dozen blocks to the south of the prison. The Women’s House of Detention was demolished in 1974.

Via Wikimedia

15. Miné Okubo, 17 East 9th Street

Okubo was a Japanese-American artist best known for her 1946 book Citizen 13660, in which she recounts her experience in a Japanese-American internment camp. The book was one of the first widely-circulated personal accounts of the repression and indignities faced by over 100,000 Japanese-Americans during World War II, and is considered to this day one of the most affecting pieces about that chapter in American history.

After the outbreak of World War II in Europe, Okubo began working for the Works Progress Administration’s art programs in San Francisco. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 called for the imprisonment of thousands of Japanese and Japanese-Americans living on the west coast. Mine and her brother Toku were relocated to internment camps in San Bruno, California and then to Utah, where they lived in harsh conditions with about nine thousand other Japanese-Americans.

Okubo documented her experience at the camp in her sketchbook, recording images of the humiliation and everyday struggles of internment. When she was freed from the camp, Mine moved to New York City, residing at 17 East 9th Street. There she completed her work turning her sketchbook into Citizen 13660, named for the number assigned to her family unit. Citizen 13660 is considered a classic of American literature and a forerunner of the graphic novel and memoir.

Via Wikimedia

16. Edie Windsor, 2 Fifth Avenue

Edie Windsor (1929-2017) may have done more than any single individual to advance the cause of gay marriage in the United States. Her 2013 Supreme Court case was the first legal victory for gay marriage in the highest court in the land, striking down the ‘Defense of Marriage’ Act and forcing the federal government and individual states to recognize same-sex marriages legally performed in other U.S. states and countries. This led directly to the 2015 Supreme Court decision recognizing gay marriage nationally.

Windsor had sued to have the federal government to recognize her marriage to longtime partner Thea Speyer, which had been legally performed in Canada. Windsor met Speyer at Portofino Restaurant at 206 Thompson Street in Greenwich Village in 1963. In the 1950s and ’60s, Portofino was a popular meeting place and hangout for lesbians. Speyer and Windsor lived at 2 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village until their respective deaths in 2009 and 2017.

17. Crystal Eastman, 27 West 11th Street

Throughout her life, Crystal Eastman was a prolific advocate for women’s rights. Her 1910 report ‘Work Accidents and the Law’ resulted in the first workers’ comp law, which she drafted herself. She co-founded the National Woman’s Party with Alice Paul and Lucy Burns and during the First World War helped found the Women’s Peace Party. She was also a member of the Heterodoxy Club. In 1917, she created The Liberator, a radical journal of politics, art, and literature, with her younger brother Max. The Liberator was based at 138 West 13th Street and they lived together in the building at 27 West 11th Street. Eastman died in 1928 and has since been called one of the most neglected leaders in United States History, having disappeared from historical memory for 50 years after her death.

Via The U.S. National Archives on Flickr

18. Eleanor Roosevelt, 29 Washington Square West

Eleanor Roosevelt, 29 Washington Square West

During her time as First Lady, from 1933 to 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt changed the role from the passive hostess to active political leader and became an outspoken politician in her own right. She held press conferences on important issues such as women’s rights and children’s causes and led marches and protests. After the death of President Franklin Roosevelt in 1945, she resided at 29 Washington Square West until 1949. She later became a U.S. delegate to the United Nations, chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights, and is widely regarded as one of the most renowned civil rights activists of the 20th Century.

Lorraine Hansberry singing with Nina Simone (1963); via NYPL, Music Division

19. Lorraine Hansberry, 335-337 Bleecker Street & 112 Waverly Place

Born in 1930, Lorraine Hansberry was a playwright and activist most commonly associated with Chicago, despite attending school and living much of her life in Greenwich Village. In 1953, she married Robert Nemiroff, and they moved to an apartment at 335-337 Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. It was during this time that she wrote A Raisin in the Sun, the first play written by a black woman to be performed on Broadway. The play brought to life the challenges of growing up on the segregated South Side of Chicago, telling the story of a black family’s challenges in trying to buy a house in an all-white neighborhood. Hansberry used the proceeds from Raisin to purchase the townhouse at 112 Waverly Place. Hansberry separated from Nemiroff in 1957 and they divorced in 1964, though they remained close until her death. It was revealed in later years that Hansberry was a lesbian, and had written several anonymously published letters to a lesbian magazine, The Ladder, discussing the struggles of a closeted lesbian. Sadly, she died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 34.

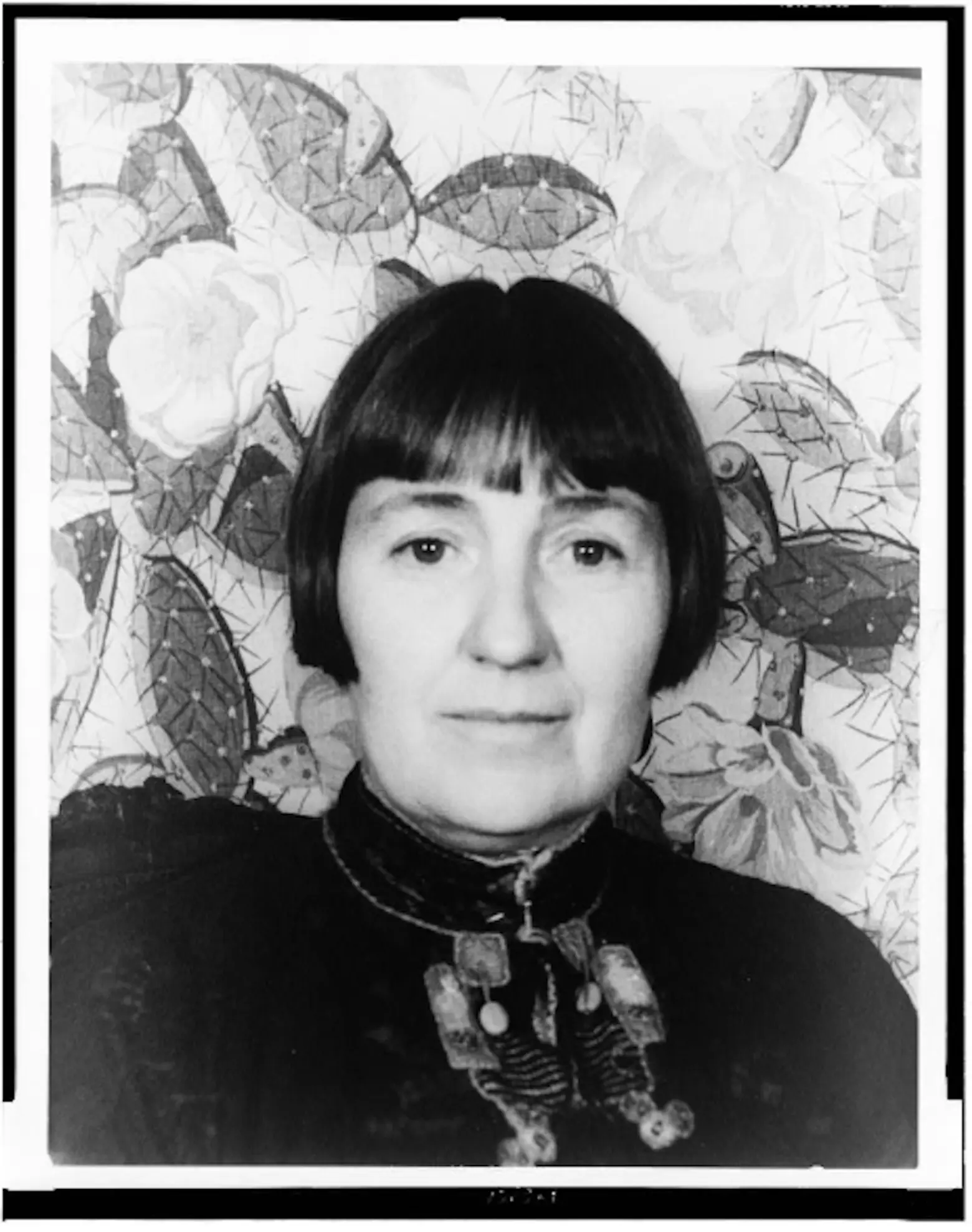

(1934) Portrait of Mabel Dodge Luhan; via Library of Congress

20. Mabel Dodge Luhan, 23 Fifth Avenue

Mabel Dodge Luhan was born into the social elite in Buffalo, New York. While living in New York City in 1912, Gertrude Stein introduced her to the Greenwich Village intelligentsia and provided Dodge’s introduction to the artists and collectors organizing the Amory Show of modern art, which is considered the event that launched Dodge. Dodge organized weekly salons in her apartment at 23 Fifth Avenue (since replaced by the building with the address 25 5th Avenue) to include a mix of intellectuals and artists. John Reed and Max Eastman met with Margaret Sanger and Charles Demuth.

Most importantly, the salons often crossed class barriers as Dodge invited those of different classes such as Emma Goldman and Bill Haywood to bring new voices into the conversations she hosted. She wrote that she wanted her guests to mix “in an unaccustomed freedom a kind of speech called Free.” Her literary solon was considered one of the most important sites of intellectual ferment during the “Greenwich Village Renaissance” of the early 20th century.

RELATED:

- 15 female trailblazers of the Village: From the first woman doctor to the ‘godmother of punk’

- Brownstones and ballot boxes: The fight for women’s suffrage in Brooklyn

- Women’s History Month began in New York in 1909 to honor the city’s garment workers’ strike

+++

For updates and more details about the Greenwich Village Historic District 50th anniversary and a full roster of events, click here >>

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid