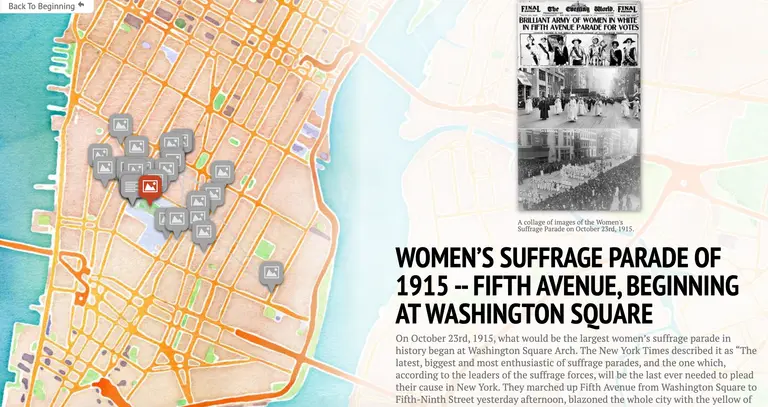

23 LGBT landmarks of the East Village and Noho

Their neighbor to the west Greenwich Village may be more well known as a nexus for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender history, but the East Village and Noho are chock full of LGBT culture as well, from the site of one the very first LGBT demonstrations to the homes of some of the greatest openly-LGBT artists and writers of the 20th century to the birthplace of New York’s largest drag festival. Ahead, we round up 23 examples, from Walt Whitman’s favorite watering hole to Allen Ginsberg’s many local residences to Keith Haring’s studio.

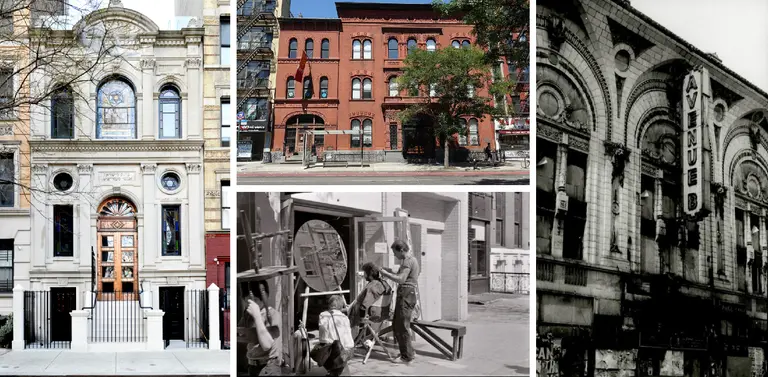

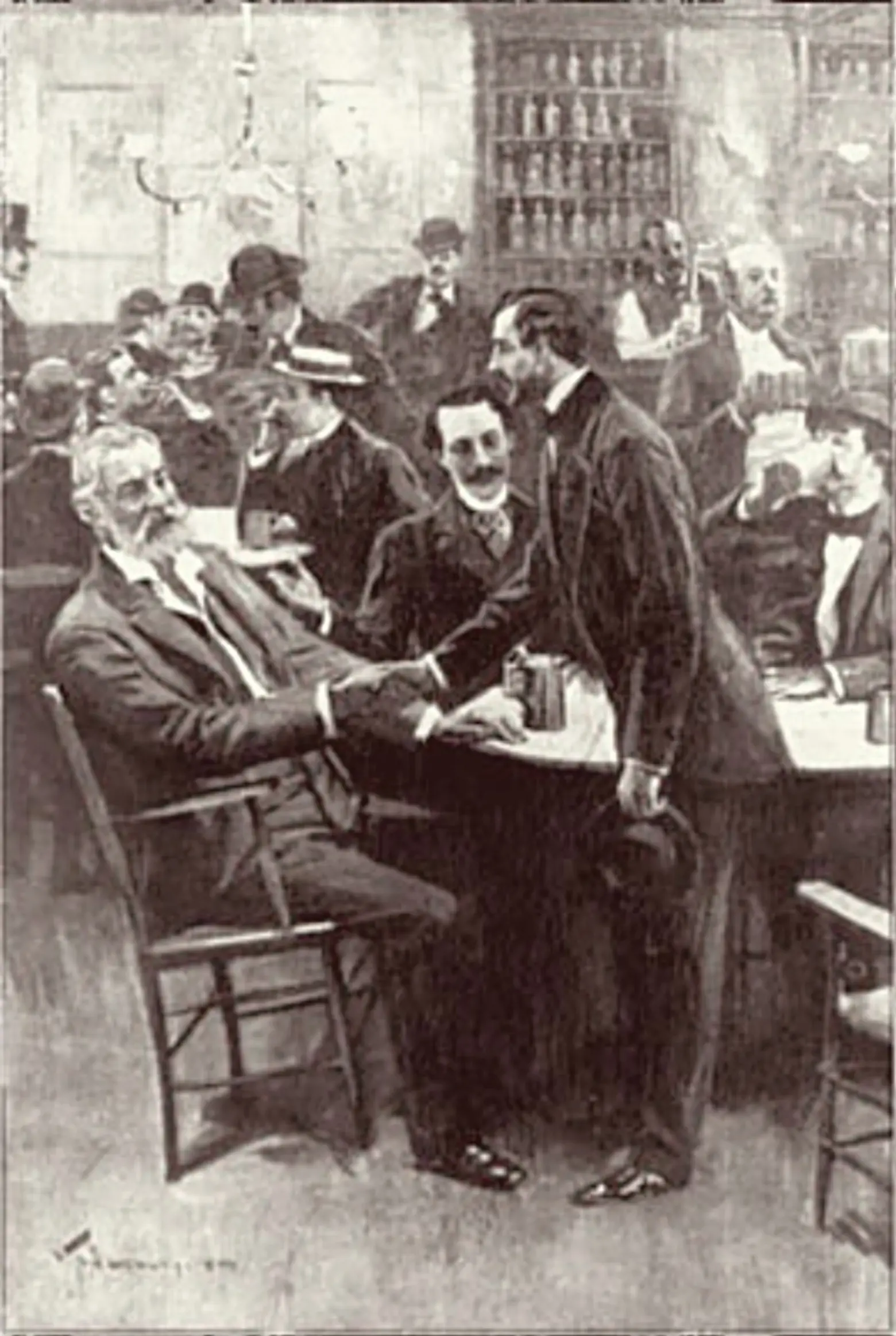

Pfaff’s beer cellar in 1857 with Walt Whitman seated, via Wiki Commons

Pfaff’s beer cellar in 1857 with Walt Whitman seated, via Wiki Commons

1. Pfaff’s, 647 Broadway

This beer and wine cellar in the lower level of what was once a hotel operated from 1859 to 1864 as the premiere bohemian haunt for New Yorkers and was known as a place for men who were attracted to other men. Among its most prominent devotees was Walt Whitman, who along with his lover Fred Vaughn often came here from their home in Brooklyn. Pfaff’s was also home to the Fred Gray Association, “a loose confederation of young men who seemed anxious to explore new possibilities of male-male affection.”

Google Street View of 676 Broadway

Google Street View of 676 Broadway

2. Keith Haring studio, 676 Broadway

The openly-gay Haring had a loft studio on the fifth floor of this building from 1985 until his death from AIDS in 1990. In the 1980s Haring revolutionized contemporary art, bringing back pop sensibilities and elevating graffiti and street art to high-art status. Haring’s artwork often directly confronted homophobia and AIDS-phobia and celebrated same-sex love, including safe-sex-oriented works he created for the group ACT-UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and his sexually explicit murals at the LGBT Community Center in Greenwich Village.

Google Street View of 381 Lafayette Street

Google Street View of 381 Lafayette Street

3. Robert Rauschenberg home and studio, 381 Lafayette Street

Rauschenberg’s groundbreaking work began in the 1950s when he, like others of the “New York School” of artists, broke the mold with their fiery abstract expressionism. But Rauschenberg developed a vocabulary all his own, at once showing the influence of Dadaism and anticipating pop art. Rauschenberg lived and worked out of this former chapel just north of Great Jones Street when the street was littered with hypodermic needles and drug paraphernalia (the term “jonesing” is said to originate from the stream of heroin addicts who would congregate on Great Jones Street).

Rauschenberg was involved in a relationship with fellow downtown artist Jasper Johns, whose studio was not far away on Houston Street. He did little to hide his sexuality, though, in the much more repressive 1950s and ’60s, he did not talk much about it publicly or explicitly reference it in his art either. The building is now the home of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

24 Bond Street, via Wiki Commons

24 Bond Street, via Wiki Commons

4. Robert Mapplethorpe home and studio, 24 Bond Street

Unlike Rauschenberg, Mapplethorpe, who came of age as an artist in the 1970s and ’80s, was quite open about his sexuality and explicitly integrated it into his art, causing worldwide controversies. His black and white photographs were stunningly beautiful portraits of his subjects, which might be his former girlfriend/collaborator Patti Smith, flower still-lifes, celebrity portraits, or participants in bondage, discipline, and Leather/S&M sex play, including a notorious self-portrait with a bullwhip inserted in his anus. Mapplethorpe’s sexually-charged imagery set off a national debate about federal funding for the arts in the late 1980s which raged for years. Mapplethorpe lived and worked on the fifth floor of 24 Bond Street from the early 1970s until his death in 1989.

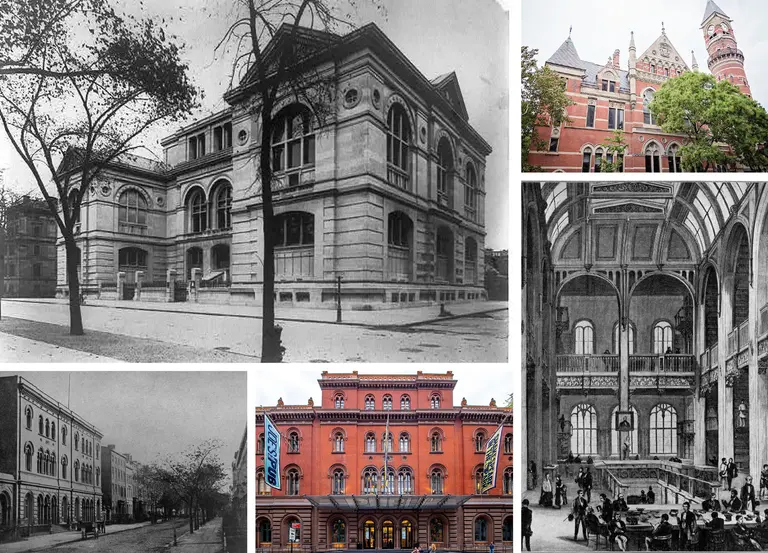

Cooper Union, via Wiki Commons

Cooper Union, via Wiki Commons

5. Cooper Union Great Hall

On December 2, 1964, gay rights activists Randy Wicker, Kay Tobin, and Craig Rodwell staged a picket in front of the Cooper Union Great Hall, protesting a talk conducted by Dr. Paul Dince titled “Homosexuality, A Disease.” The previous September, Wicker had organized another action at the U.S. Army Building at Whitehall Street, drawing attention to the military’s discriminatory treatment of gay people. Together, these rallies have come to be known as the first public demonstrations for gay rights in the United States.

The Great Hall protest was also the first public protest of the profession of psychiatry, which formulated and perpetuated prejudiced “science” targeting the LGBT community. Outside the Great Hall, the protestors passed out flyers and demanded 10 minutes of rebuttal time after the talk. The forum chairman, eager to facilitate a dialogue, accepted, and Wicker took the microphone immediately after the lecture, receiving enormous applause from the audience.

In the 1990s, the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP) held its Monday night general meetings at the Great Hall, once its meeting attendees could no longer fit inside the LGBT Community Center on West 13th Street. ACT UP worked to galvanize political action to protest policies that inhibited the fight against AIDS and has grown to be a national and international organization.

Google Street View of 61 Fourth Avenue

Google Street View of 61 Fourth Avenue

6. Robert Indiana studio, 61 Fourth Avenue

The openly-gay artist, best known for his iconic “LOVE” sculpture, lived and worked here in the 1950s when this area south of Union Square was the center of the New York School of artists and the art world.

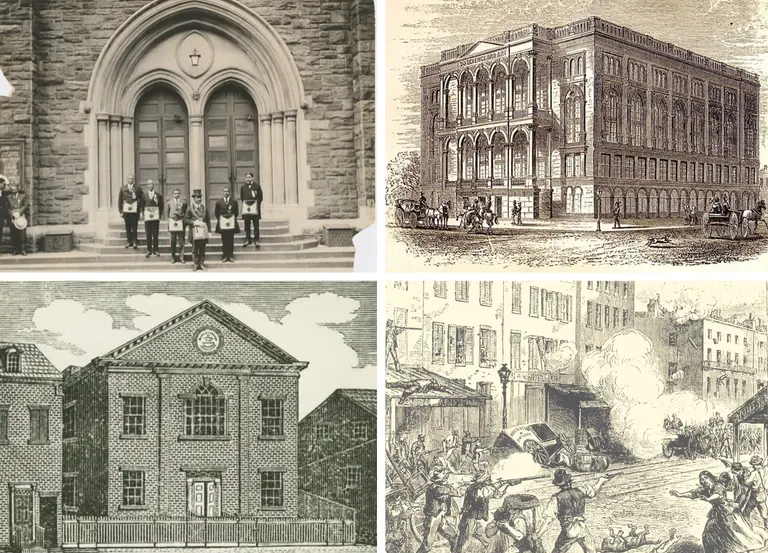

Webster Hall, via Wiki Commons

7. Webster Hall, 125 East 11th Street

This world-famous gathering hall, which in its early years was the scene of union rallies and political organizing, was also known for its drag balls in the 1910s and ’20s which were the place for gay, lesbian, and transgender New Yorkers to see and be seen. It also welcomed “free love” advocates such as speakers like Emma Goldman. In the post-War II years, Webster Hall became a recording studio, and in the 1980s, a dance and musical performance venue.

Before-and-after of 222 East 13th Street, courtesy of the Cooper Square Committee and the Ali Forney Center

Before-and-after of 222 East 13th Street, courtesy of the Cooper Square Committee and the Ali Forney Center

8. Bea Arthur Transitional Residence for LGBT Youth, 222 East 13th Street

In 2018, this long-abandoned building, which originally dates to the 1840s, was renovated and reopened as safe, quality transitional housing for homeless LGBT teenagers and young adults. The actress Bea Arthur funded the project before her death in 2009. Undertaken by the Cooper Square Committee and the Ali Forney Center, the project is a first-of-its-kind transitional housing for LGBT youth.

62 East 4th Street, via Wiki Commons

62 East 4th Street, via Wiki Commons

9. Andy Warhol’s Theater: Boys to Adore Galore, 62 East 4th Street

In 1969, Andy Warhol rented what was then called the Fortune Theater for a series of showings of hardcore gay porn films. The entire factory set was involved – Paul Morrissey masterminded the operation, Gerard Malanga ran the house, Jim Carroll was the ticket-taker, and Joe Dallesandro was the projectionist. According to Carroll, Dallesandro was also making extra money by offering sex for pay to patrons in a side room of the theater. In the early ’70s, drag queens/Warhol superstars Jackie Curtis, Holly Woodlawn, and Candy Darling each hosted productions there.

Emma Goldman addressing a rally at Union Square in 1916, via Wiki Commons

Emma Goldman addressing a rally at Union Square in 1916, via Wiki Commons

10. Emma Goldman Residence, 208-210 East 13th Street

The anarchist known as “the most dangerous woman in America” lived here from 1903 to 1913, and her publication Mother Earth was produced here beginning in 1906. Among Goldman’s most radical and controversial views were support for “free love” and the rights of homosexuals, bisexuals, and transgender people. She condemned the persecution of Oscar Wilde and was called “the first and only woman, indeed the first and only American, to take up the defense of homosexual love before the general public.” Goldman regularly addressed the subject in her widely heard public speeches, as well as in the pages of Mother Earth.

59 East 4th Street, courtesy of Village Preservation

59 East 4th Street, courtesy of Village Preservation

11. WOW Café, 59 East 4th Street

The Women’s One World Café Theater bills itself as “the oldest collectively run performance space for women and/or trans artists in the known universe.” Founded in 1980, the group has been located here since 1984. From its inception, WOW has prominently featured lesbian/queer artists and is considered one of the premier venues for lesbian theater in New York.

Google Street View of La Mama Theater at 74 East 4th Street

Google Street View of La Mama Theater at 74 East 4th Street

12. La MaMa Theater and Annex, 66-68 and 74 East 4th Street

Considered one of the oldest, most influential, and most respected Off Broadway Theaters, La MaMa has consistently featured the works of LGBT playwrights, even when few would. Among those whose work has appeared here are Harvey Fierstein, Charles Ludlam, Lanford Wilson, Terrence McNally, and Jean-Claude van Itallie.

Google Street View of 82 East 4th Street

Google Street View of 82 East 4th Street

13. 82 Club, 82 East 4th Street

From 1953 to 1978, the legendary drag cabaret the 82 Club was located here, called “the biggest drag show in America.” Both male and female cross-dressing performers graced the stage, served as bouncers, and waited tables. Run by mob boss Vito Genovese when anti-gay laws made all such spaces technically illegal, the club was used to launder money, blackmail patrons, and stash drugs. None of that stopped the adventurous Hollywood elite from stopping by, including Frank Sinatra, Kirk Douglas, Elizabeth Taylor, Judy Garland, and Errol Flynn (the latter of whom once felt free in the club’s ribald atmosphere to walk up to the piano and start tickling the ivories with his penis).

In the 1970s, the club took on a very different character as it began to attract a glam rock crowd, including Lou Reed, David Bowie, the New York Dolls, and the Stilettos (Debbie Harry’s pre-Blondie band). Harvey Fierstein performed there, and the club made an appearance in Torch Song Trilogy.

The Yiddish Art Theater today, photo © James and Karla Murray

The Yiddish Art Theater today, photo © James and Karla Murray

14. Yiddish Art Theater, 181-189 Second Avenue

Now a movie theater, the Yiddish Art Theater contains apartments above the ticket window, which in the 1970s through 1990s were occupied by a series of prominent LGBT artists, including Warhol superstar Jackie Curtis, photographer Peter Hujar, and artist David Wojnarowicz. But the building’s LGBT roots extend far deeper – literally and figuratively. From 1945 to 1953, the basement of the theater was home to the 181 Club, sometimes referred to as “the Homosexual Copacabana.” The club featured “female impersonator” performers, butch lesbian waiters in tuxedos, and was lavishly decorated by its mafia-owners, attracting straight gawkers and LGBT people as customers. Following the club’s closure in 1953, until 1961 the building was home to the Phoenix Theater, a highly-regarded Off-Broadway venue that featured many LGBT performers, including Montgomery Clift, Farley Granger, and Roddy McDowall.

105 Second Avenue today, via Wiki Commons

105 Second Avenue today, via Wiki Commons

15. The Saint, 105 Second Avenue

Housed in what was originally a Yiddish Theater and from 1968 to 1971 the Fillmore East, The Saint nightclub opened here in the fall of 1980, becoming New York’s largest and most celebrated gay disco. The space was transformed into a state-of-the-art dance venue, with a planetarium-like dome, 1,500 lights, and 500 speakers, many placed on hydraulic lifts. At least initially, entry was members-only, with memberships costing as much as $250, and a capacity of up to 4,000 people with a 5,000-square- foot central dance floor. The Saint defined New York nightlife in the 1980s, attracting a who’s who of performers. The onset of the AIDS epidemic, however, created significant financial and operational challenges for the club, which closed in 1988 after a 48-hour non-stop party.

46 East 3rd Street, via CityRealty

46 East 3rd Street, via CityRealty

16. Quentin Crisp residence, 46 East 3rd Street

This former 1830s rowhouse became a single-room occupancy rental apartment building in the late 20th century, and its most illustrious resident was the openly gay writer and actor Quentin Crisp, who lived here from 1981 until his death in 1999. Crisp was perhaps best known for his 1968 autobiography “The Naked Civil Servant,” which was made into a TV mini-series in 1975. The series was a surprise worldwide hit, focusing on Crisp’s struggles as an openly gay man in the face of the repressive mores of England in the 1950s and ’60s, as well as his time as a prostitute.

Crisp was also known for his witty rejoinders, such as his response to an American immigration official questioning if he was “a practicing homosexual,” to which he is said to have replied “I don’t need to practice, I’m already perfect.” His 1990 obituary in The New York Times reads: “Mr. Crisp was a neighborhood celebrity known for his wardrobe of splashy scarves, his violet eyeshadow and his white hair upswept a la Katharine Hepburn and tucked under a black fedora. His nose and chin were often elevated to a rather imperious angle, and his eyebrows were painstakingly plucked. When he played the role of Queen Elizabeth I in Sally Potter’s 1993 film ‘Orlando,’ Village residents bowed before him on the sidewalks as he passed.”

Google Street View of 77 St. Mark’s Place

Google Street View of 77 St. Mark’s Place

17. W.H. Auden residence, 77 St. Marks Place

The renowned poet, another English transplant to the East Village, lived in a tiny apartment here from 1953 until 1972. The lover of writer Christopher Isherwood and poet Charles Kallman, he was fairly open about his sexuality during his lifetime, with one of his most celebrated poems, 1938’s “Funeral Blues,” a haunting elegy to a departed male love. It begins with the unforgettable line describing his reaction to the news of his death, “stop all the clocks.”

Google Street View of 52 East 1st Street

Google Street View of 52 East 1st Street

18. Ana Maria Simo Residence, 52 East 1st Street

The building was home to Ana Maria Simo, a playwright, essayist, and novelist. Born in Cuba and educated in France, Simo made important contributions as a lesbian activist. In 1976, she founded Medusa’s Revenge, the first lesbian theater in New York City, with actor and director Magaly Alabau. The Lesbian Avengers, a direct action group focused on issues of lesbian survival and visibility, was founded in her apartment in 1992 by Simo and lesbian activists Maxine Wolfe, Anne-Christine d’Adesky, Sarah Schulman, Marie Honan, and Anne Maguire. The Lesbian Avengers inspired chapters all over the world and began the annual Dyke March in New York City, which traditionally kicks of LGBT Pride Weekend.

Google Street View of 441 East 9th Street

Google Street View of 441 East 9th Street

19. Frank O’Hara residence, 441 East 9th Street

The openly-gay “New York School” poet lived here with his sometimes lover Frank LeSueur from 1959-1963, during one of the most productive periods of his career. He published “Second Avenue” and “Odes” while here, and wrote most of his Lunch Poems while also here, which was published in 1964. His writings often reflected and referenced his East Village surroundings.

101 Avenue A, via Village Preservation

20. Pyramid Club, 101 Avenue A

Located in an 1876 tenement ground floor which had served as a German social hall and jazz club over the years, the Pyramid Club opened here in 1979, becoming one of the defining venues of the downtown club scene of the 1970s and ’80s and the sole surviving music club from that era. The Pyramid Club has been credited with creating the East Village drag and gay scenes of the 1980s, launching a new politically-conscious form of drag performance art in the early 1980s. Noted drag performers including Lypsinka, Lady Bunny, and RuPaul emerged from the Pyramid Club. It was also here that the annual Wigstock festival began in 1984 when a group of the club’s drag queens performed a spontaneous drag show at Tompkins Square Park. Madonna appeared at her first AIDS benefit here. New York Magazine referred to it as “A temple of iniquity for punk rockers, Goth betties, and queers of every feather.”

Tompkins Square Park via Flickr cc

Tompkins Square Park via Flickr cc

21. Tompkins Square Park

Tompkins Square Park was the original location of the annual Wigstock Festival when it began in 1984. Created by Lady Bunny, Wigstock was an outdoor drag festival held each year on Labor Day to act as the unofficial end of summer for the gay community in New York City. It began when a group of drag queens from the nearby Pyramid Club performed a spontaneous drag show in the park. Crowds grew each year, and the festival moved, first to Union Square Park, then to the piers on the Hudson River. Though Lady Bunny said that the 2001 festival would be the last, it returned in 2003 under the auspices of the Howl Festival.

The Nuyorican Poets Café at 236 East 3rd Street via Flickr cc

The Nuyorican Poets Café at 236 East 3rd Street via Flickr cc

22. Nuyorican Poets Café – 505 East 6th Street and 236 East 3rd Street

Founded in 1973, the Nuyorican Poets Café was originally located at 505 East 6th Street, but since 1981 has been located at 236 East 3rd Street in a five-story tenement the organizations now owns. One of the co-founders was the noted openly-gay Puerto Rican playwright and actor Miguel Pinero. The themes of his work, dealing with Pinero’s own impoverished upbringing, gang life, and time in prison, greatly influenced and shaped the Nuyorican poetry and literature movement. Allen Ginsberg, a regular at Nuyorican Poets Cafe, called it “the most integrated place on the planet,” noting the racial, gender, and sexuality diversity of the poets and audience, reflecting the organization’s ethos of inclusivity and giving voice to the voiceless.

The now-demolished Mary Help of Christians Church, via Wiki Commons

23. Allen Ginsberg Residences – 404 East 14th Street, 170 East 2nd Street, 406-408 East 10th Street, 206 East 7th Street, and 437-439 East 12th Street

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg lived all over the East Village and was a permanent fixture in the neighborhood’s bars, parks, and cultural spaces until his death in 1997. He frequently referenced his East Village surroundings in his work, including the bells of Mary Help of Christians Church on East 12th Street, which he lived opposite from 1975 to 1996. The openly-gay Ginsberg broke through the enforced silence of the 1950s around topics like homosexuality, unconventional spirituality, and drugs in his works. He lived in the East Village with a series of lovers, including Peter Orlovsky, and other openly-gay writers, including William Burroughs, at the East 7th Street apartment.

RELATED:

- 17 LGBT landmarks of Greenwich Village

- 15 things you didn’t know about the East Village

- 50 ways to celebrate Stonewall 50 and Pride Month in NYC

+++

This post comes from Village Preservation. Since 1980, Village Preservation has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid

Webster Hall photo in lead image via Wally Gobetz/Flickr