52 years ago, Donald Trump’s father demolished Coney Island’s beloved Steeplechase Park

Steeplechase Park circa 1930-45, via Digital Commonwealth

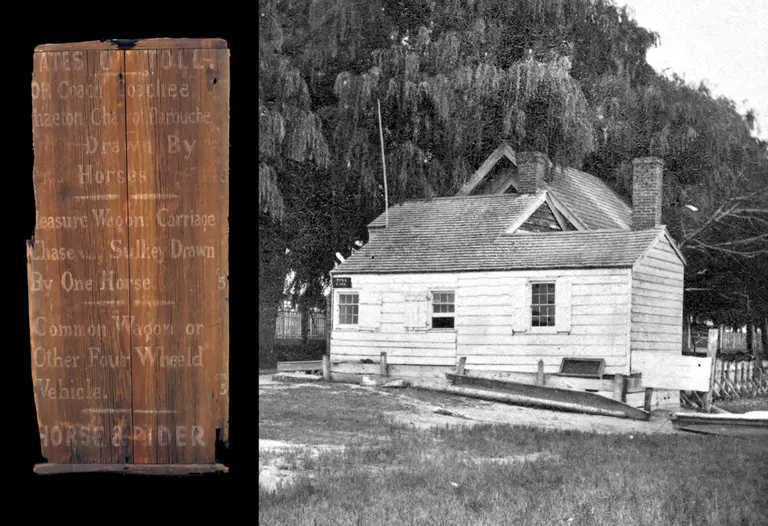

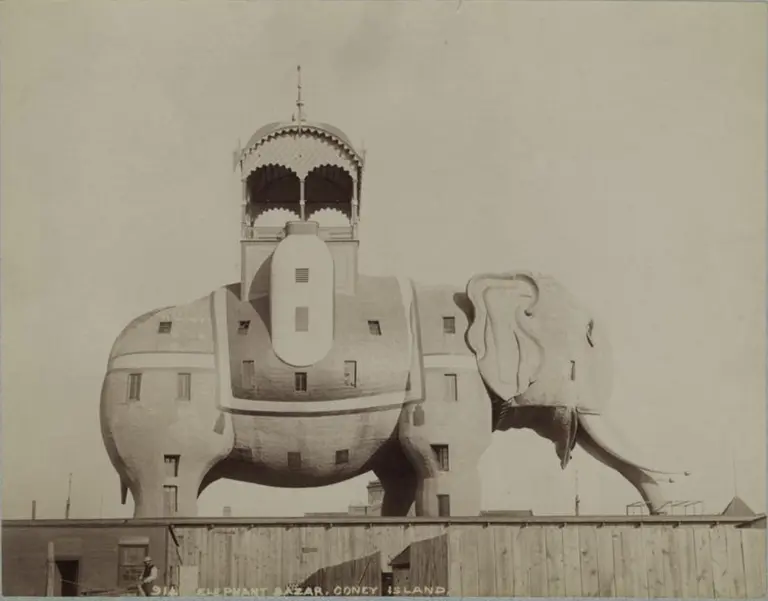

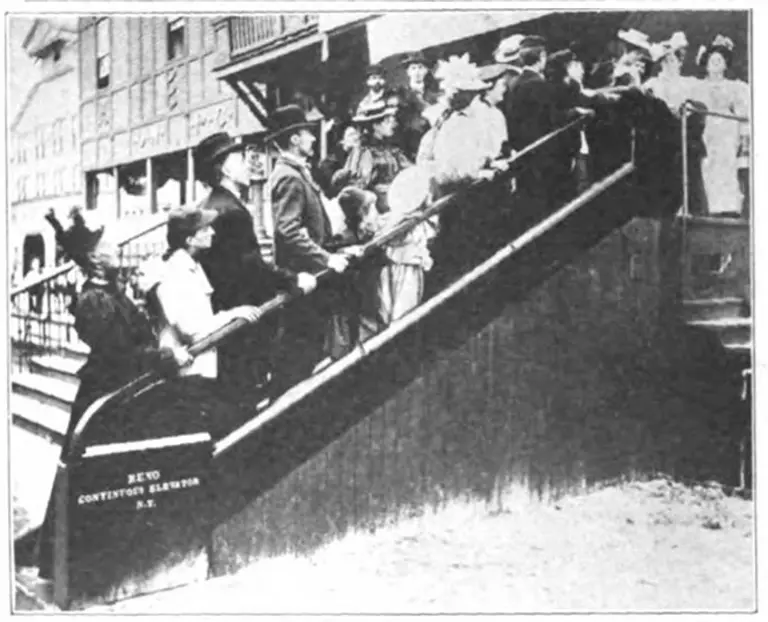

Steeplechase Park was the first of Coney Island‘s three original amusement parks (in addition to Luna Park and Dreamland) and its longest lasting, operating from 1897 to 1964. It had a Ferris Wheel modeled after that of Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition, a mechanical horse race course (from which the park got its name), scale models of world landmarks like the Eiffel Tower and Big Ben, “Canals of Venice,” the largest ballroom in the state, and the famous Parachute Jump, among other rides and attractions.

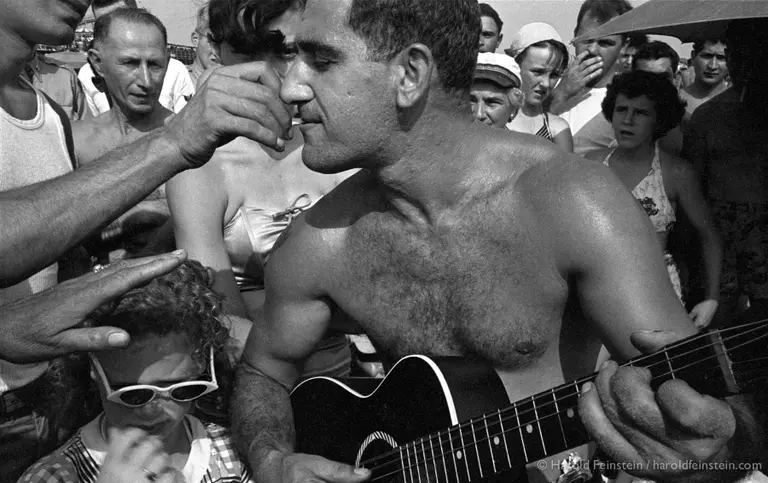

After World War II, Coney Island’s popularity began to fade, especially when Robert Moses made it his personal mission to replace the resort area’s amusements with low-income, high-rise residential developments. But ultimately, it was Fred Trump, Donald’s father, who sealed Steeplechase’s fate, going so far as to throw a demolition party when he razed the site in 1966 before it could receive landmark status.

George Tilyou opened Steeplechase Park in 1897. His parents ran the famous Surf House resort, popular among Manhattan and Brooklyn city officials, so George grew up on the boardwalk. He started his career in real estate, but after visiting the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, he knew he wanted to bring the Ferris Wheel (then a brand new engineering feat) to Coney Island. His was half the size, but nothing like it existed outside Chicago, so it quickly became Coney Island’s biggest attraction. After a few years, he decided to add other amusements around the Wheel and began charging guests 25 cents to enter the now-enclosed park. To keep visitors interested and compete with the other amusement parks popping up, he continually added new attractions, like “A Trip to the Moon,” an early motion simulator ride, and the 235-foot-long “Giant See-Saw,” which lifted riders almost 170 feet into the sky.

In July 1907, a lit cigarette thrown in a trashcan burned down Steeplechase Park, but by 1909 it was completely rebuilt with all new attractions. Three years later, George Tilyou passed away and left the park to his children, who faced the uncertainty of the entire boardwalk after World War II. Competitor Luna Park also caught fire in 1944, which led to its closure in 1946. This might sound like a good thing for Steeplechase, but it greatly depleted the overall amusements in Coney Island, fueling interest from developers. And in 1950, Luna was totally razed and rezoned for residential development.

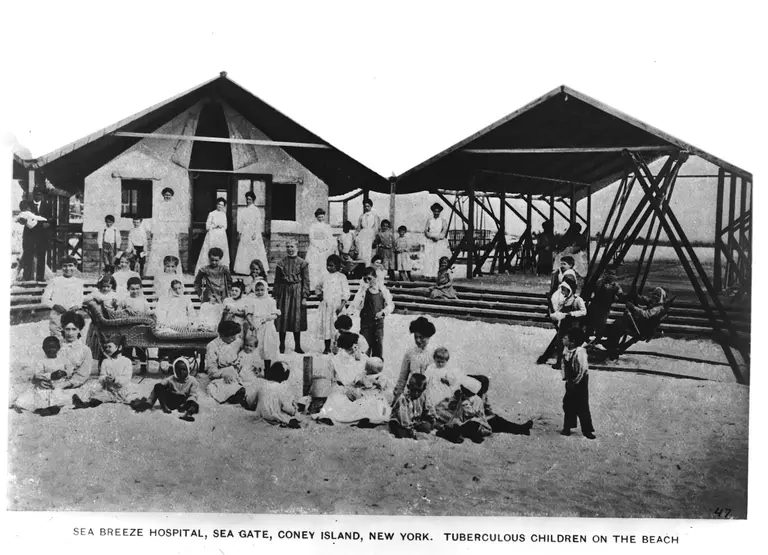

This was a sentiment echoed by “master planner” Robert Moses, who expressed his disdain for Coney Island, implying that those who went there were low-class. Beginning in the ’30s, he tried to convert the area into parkland, and in 1947 he moved the New York Aquarium to the former home of Dreamland to prevent another amusement park from opening. In the late ’50s, having served for almost a decade as the city housing commissioner, he built several high-rise, low-income residential developments, completely altering the character of the amusement area. By the ’60s, Coney Island saw a rise in crime, affecting attendance at Steeplechase and the surrounding parks.

Image of Coney Island today with residential towers in the background via Daniel Fleming / Flickr cc

Image of Coney Island today with residential towers in the background via Daniel Fleming / Flickr cc

Despite the end of Coney Island’s heyday, in 1962, a new amusement park, Astroland, opened up next to Steeplechase. It kept the east end zoned for amusements, and was beneficial to Steeplechase. But by this time, George Tilyou’s children were getting older and concerned about the park’s future. His daughter Marie was the majority stockholder, and without the blessing of her siblings, sold all the family’s Coney Island property to none other than Fred Trump (that’s right, Donald‘s father) in February 1965. She rejected other bids by local entities like Astroland and the owners of Nathan’s Famous, leading most to believe the sale to Trump was more financially lucrative as a possible residential redevelopment. Since he was unable to obtain the necessary zoning variances, it was assumed that Steeplechase would continue to operate as an amusement park until then. But Trump didn’t open it for the 1965 season, and the following year, amid efforts to landmark the park, he threw a “demolition party” where people were invited to throw bricks at the facade of Steeplechase. He then bulldozed it, thankfully sparing the beloved Parachute Jump.

MCU Park today via Tdorante10 / Wiki Commons

In a bitterly ironic twist, Trump never was able to build housing on the site, so he eventually leased it to Norman Kaufman, a ride operator who turned the property into a makeshift amusement park called Steeplechase Kiddie Park. He intended to build the park back up to its glory, but in 1981, the city (to whom Fred Trump had sold the site in 1969) wouldn’t renew his lease when other amusement operators complained of the abnormally low rent Kaufman was paying. Two years later, the city tore down any remnants of Steeplechase and turned the site into a private park, leaving this entire end of Coney Island without any amusements. For the next decade or so, many ideas for the property were floated, including one to create a new Steeplechase by KFC owner Horace Bullard, but it wasn’t until 2001 that MCU Park (formerly KeySpan Park), a minor league baseball stadium was erected. Today it’s operated by the Mets and hosts the Brooklyn Cyclones.

The Parachute Jump today via Charley Lhasa / Flickr cc

As previously mentioned, the Parachute Jump is all that remains today of Steeplechase. It was designated an official landmark in 1977 and serves as a symbol not only of Coney Island’s history as an amusement capital but of a reminder that controversy and public antics from the Trumps go back much further than Donald’s presidency.

Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on 6sqft on May 18, 2016.

RELATED: