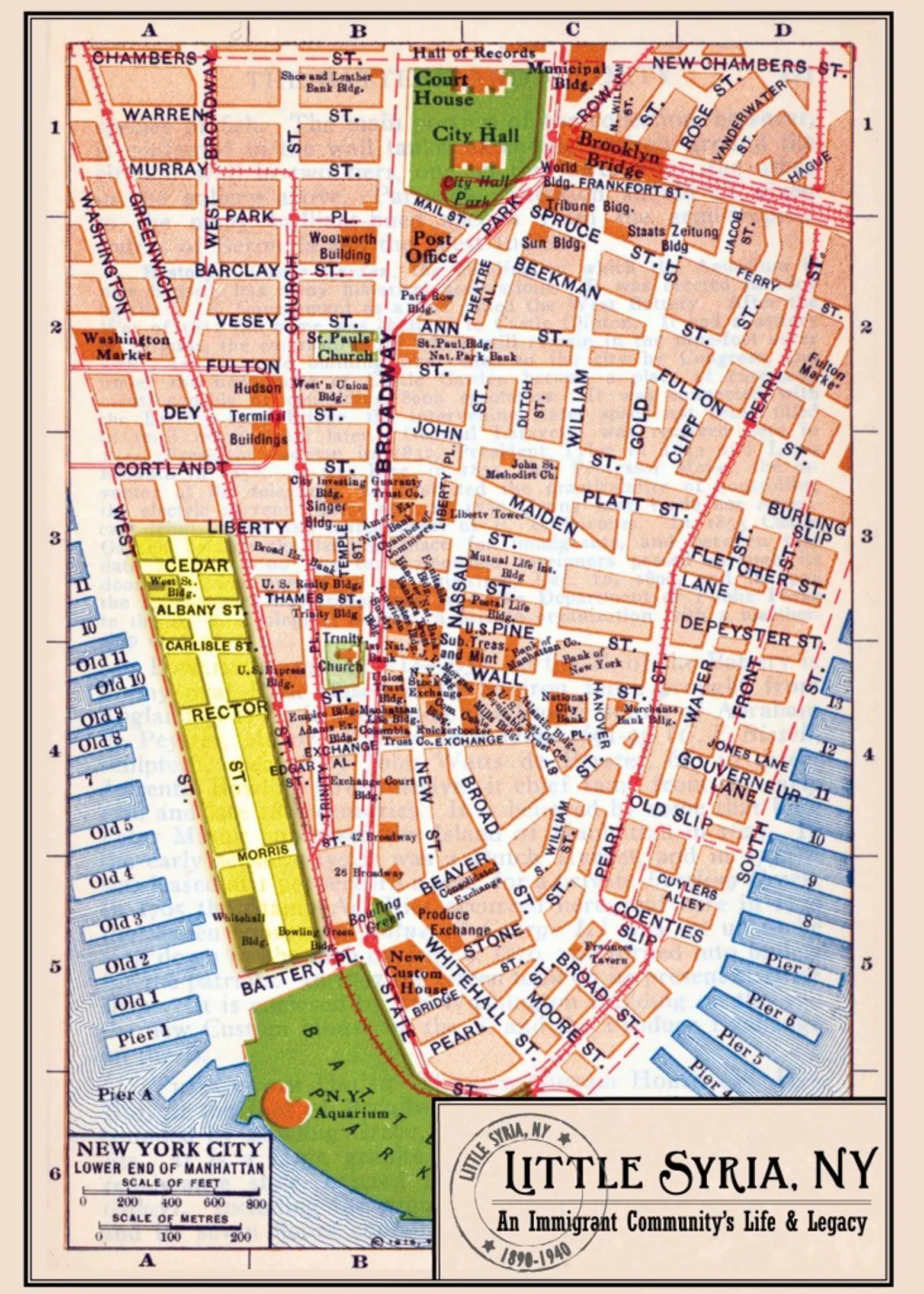

The history of Little Syria and an immigrant community’s lasting legacy

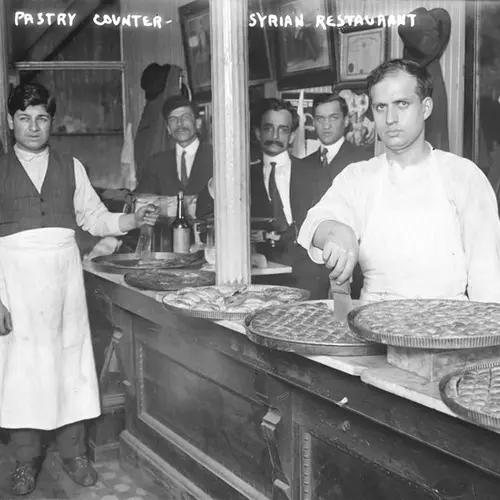

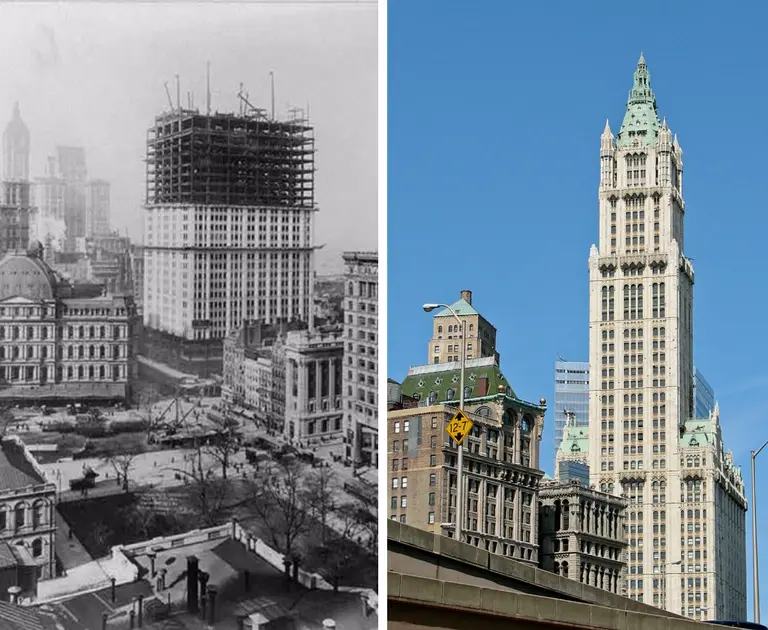

In the light of Donald Trump’s ban on Syrian refugees, 6sqft decided to take a look back at Little Syria. From the late 1880s to the 1940s, the area directly south of the World Trade Center centered along Washington Street held the nation’s first and largest Arabic settlement. The bustling community was full of Turkish coffee houses, pastry shops, smoking parlors, dry goods merchants, and silk stores, but the Immigration Act of 1924 (which put limits on the number of immigrants allowed to enter the U.S. from a given country and altogether banned Asians and Arabs) followed by the start of construction on the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel in 1940, caused this rich enclave to disappear. And though few vestiges remain today, there’s currently an exhibit on Little Syria at the Metropolitan College of New York, and the Department of Parks and Recreation is building a new park to commemorate the literary figures associated with the historic immigrant community.

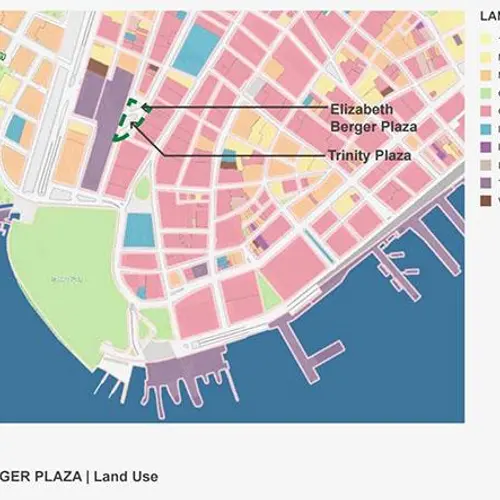

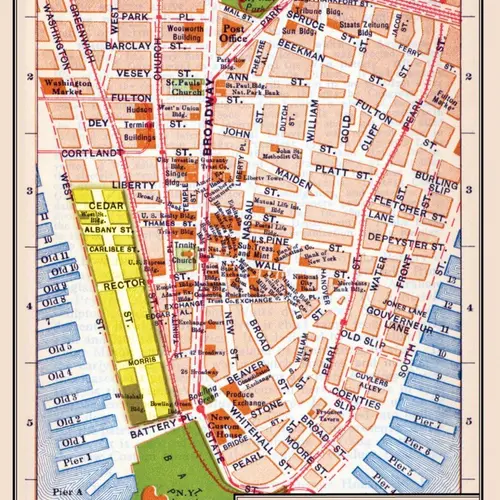

Map courtesy of the Arab American National Museum

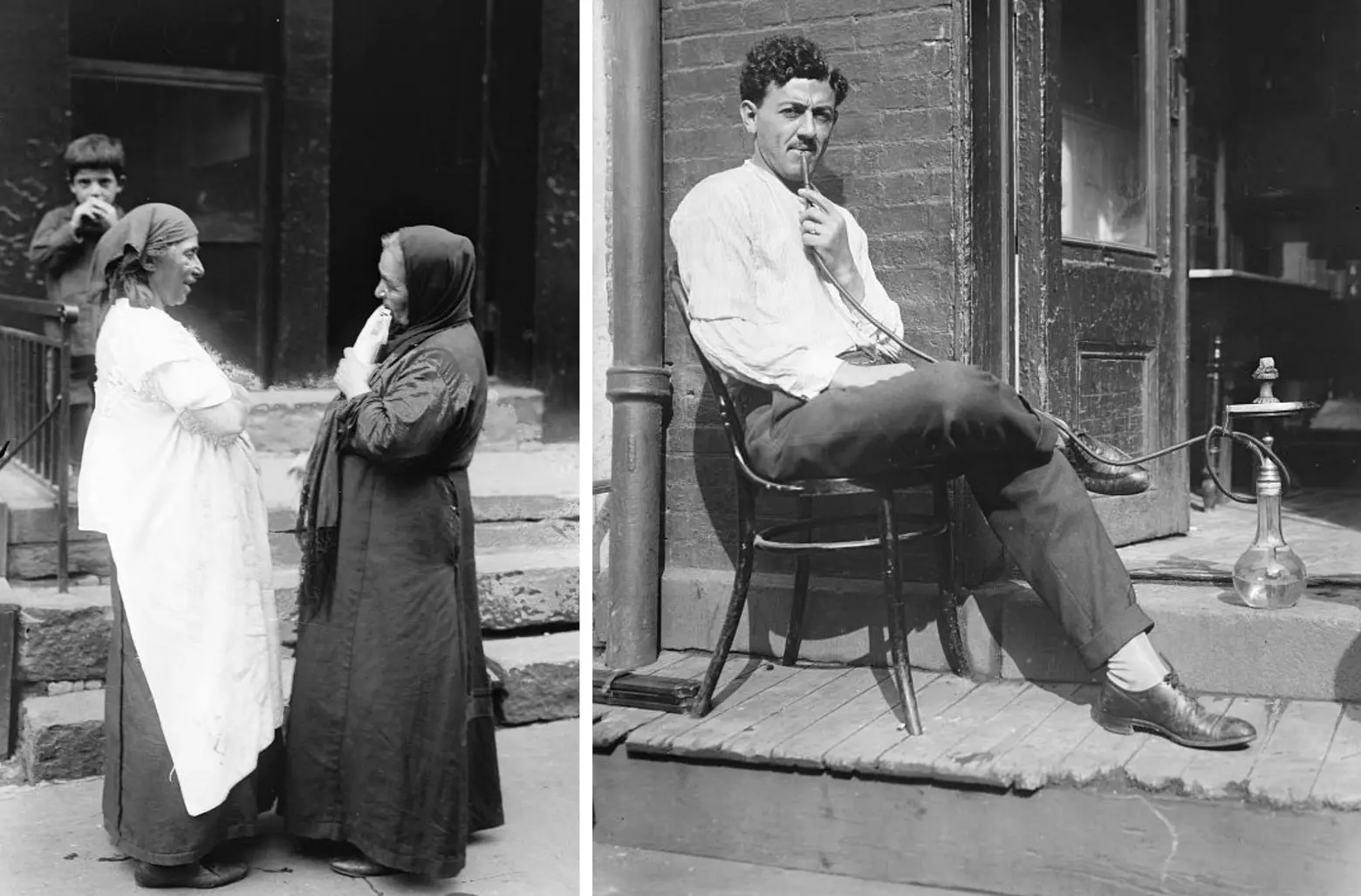

Syrian children on Washington Street in 1916

Syrian children on Washington Street in 1916

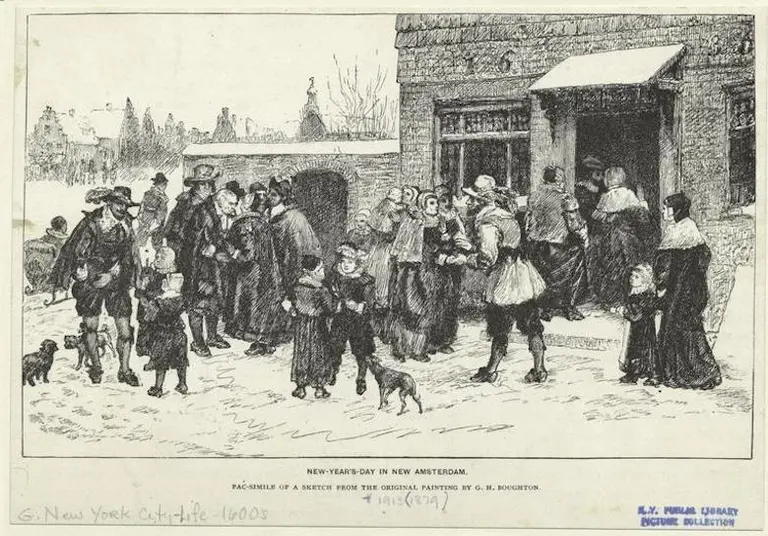

In the late 1800s, thousands of immigrants from Greater Syria–today’s Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine–arrived to New York City, many of whom were escaping religious persecution and poverty under the Ottoman Empire. Welcomed by American missionaries, the immigrants settled in Little Syria, or the Syrian Quarter, the area around Washington Street, from Battery Park to Rector Street, because of its proximity to the docks, where the men could find work.

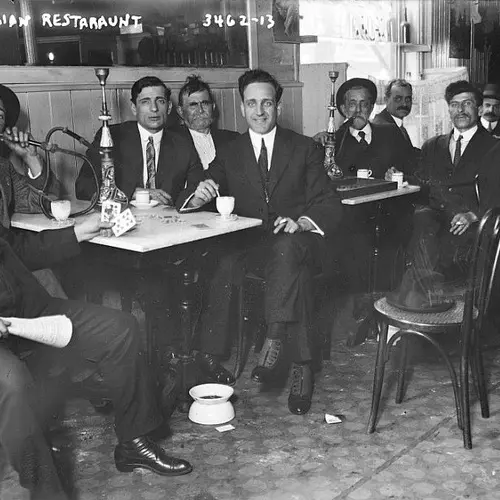

The Lebanon Restaurant at 88 Washington Street in 1936, via NYPL

The Lebanon Restaurant at 88 Washington Street in 1936, via NYPL

Syrian men smoking argileh (water pipes), circa 1910-15

To give an idea of how the community thrived, by 1899 there were 3,000 immigrant residents. Most Syrian immigrants began as peddlers, but, known for their entrepreneurial spirit, they’d established over 300 businesses according to the 1908 Syrian Business Directory. By this year there were 70 linen businesses alone, most of which were staffed by women with ties to the Lebanese silk industry. In fact, Rector Street was the lingerie capital of New York.

al-Hoda’s offices in 1930, courtesy of Mary Mokarzel and the University of Minnesota Immigration History Research Center

In 1898, the country’s first Arabic language publication, al-Hoda (meaning “the guidance”), was published here by Naoum Mokarzel. The linotype machine was first fitted with Arabic letters to print this newspaper, which gave way to the more than 50 Arabic language periodicals that were printed in Little Syria between 1890 and 1940.

Other major literary figures who called Little Syria home included Lebanese author and artist Kahlil Gibran, best known for his 1923 book “The Prophet,” being the third best-selling poet ever behind Shakespeare and Laozi, and founding the Arab-American literary society called The Pen League, as well as Lebanese writer and political activist Ameen Rihani, who is considered the founding father of Arab-American literature and whose 1911 “The Book of Khalid” was the first English novel by an Arab-American writer (it was also set in Little Syria).

Most residents were Arabic-speaking Christian, Melkite (Middle-Eastern Byzantine Rite Christians), or Maronite (a Lebanese Christian denomination). They opened three churches, one of which was St. George’s Melkite Church. Located at 103 Washington Street between Rector and Carlisle Streets, it was originally erected in 1812 as a three-story structure with a peaked roof. By 1850, it was also being used as a boardinghouse for local immigrants, and so in 1869, a two-story addition was put on. The current neo-Gothic terra cotta facade was added in 1929 to the designs of Lebanese-American draftsman Harvey F. Cassab. The building received landmarks status in 2009, and today is home to St. George Tavern on the ground floor and Tipsy Shanghai restaurant on the second floor.

Only two other buildings remain from Little Syria– the Downtown Community House at at 105-107 Washington Street and the tenement at 109 Washington Street. The former is a six-story, red-brick building completed in 1926 for the Bowling Green Neighborhood Association to be used as a settlement house for the local immigrant community. The 1885 tenement building is the only remaining such structure on the lower part of Washington Street that was once home to about 50 similar buildings that housed residents of Little Syria.

The reason the rest of the tenements no longer exist has to do with the Robert Moses-led construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel in 1946. Most of the buildings were seized through eminent domain to make way for its entrance ramps, and what remained was demolished 20 years later when the World Trade Center was built.

The reason the rest of the tenements no longer exist has to do with the Robert Moses-led construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel in 1946. Most of the buildings were seized through eminent domain to make way for its entrance ramps, and what remained was demolished 20 years later when the World Trade Center was built.

During this time, many former Little Syria residents moved to Altantic Avenue in Brooklyn’s Cobble Hill, where a thriving Middle Eastern culture still exists today. One of this area’s most famous spots is Sahadi’s, a Lebanese gourmet grocery store that originally opened in the 1890s on Washington Street as A. Sahadi & Co., but moved to Atlantic in 1948. There are also plenty of other speciality food stores along the strip selling goods like Zaatar, hummus, and baklava, as well as several Lebanese and Syrian restaurants offering up plates of mezze.

In 2012, a preservation advocacy group called the Washington Street Historical Society petitioned the Landmarks Preservation Commission to also designate 105-107 Washington Street and 109 Washington Street, but the request has yet to be granted. They did, however, successfully raise $15,000 after Hurricane Sandy for improvements at Edgar Street Park–the closest park to the historic neighborhood, at Trinity Place and Greenwich Street–that included a historic sign commemorating Little Syria and six bench plaques pertaining to Washington Street’s history and a few famous figures from the time.

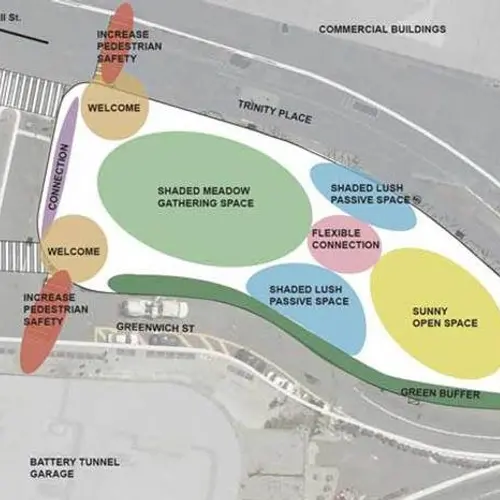

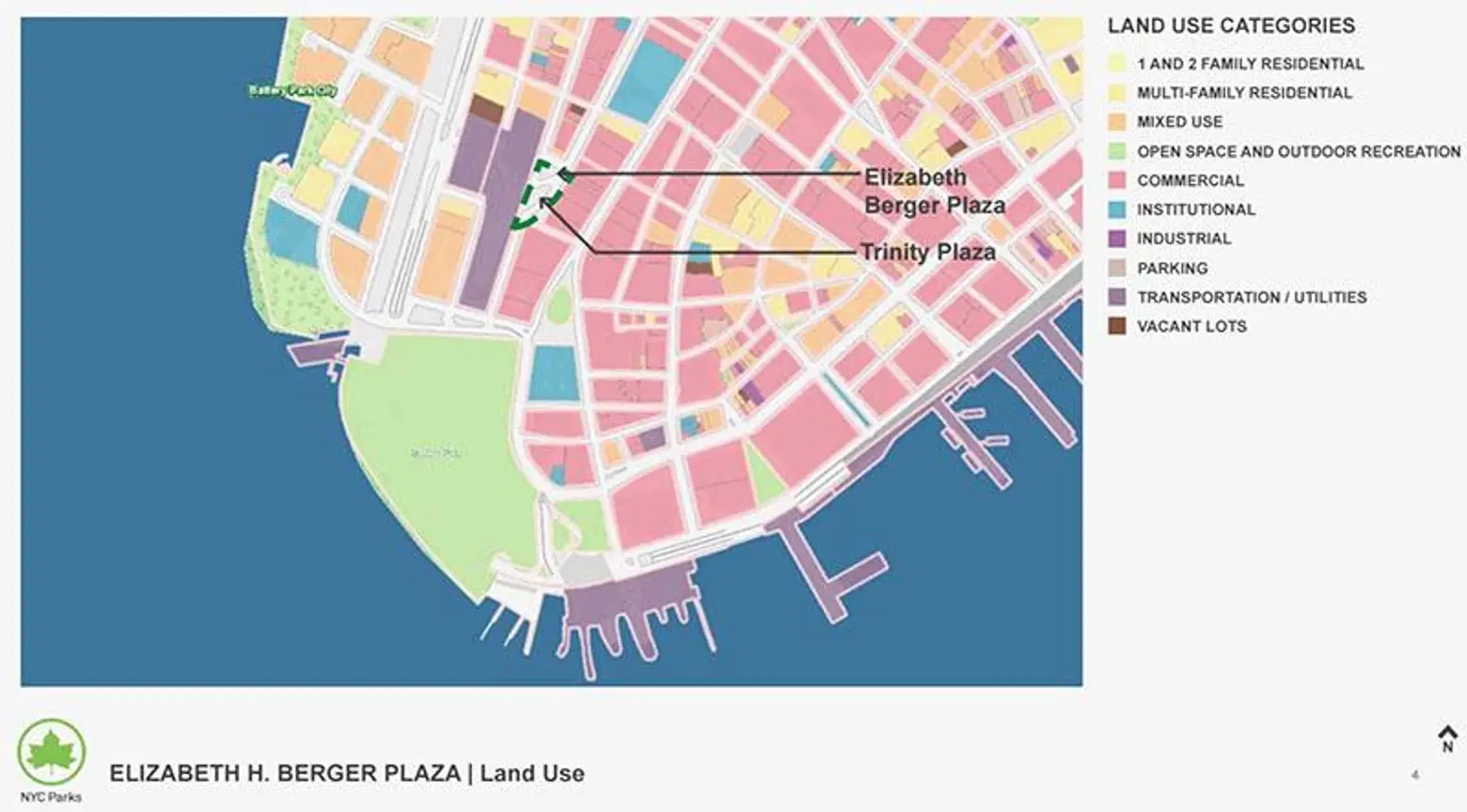

Renderings of Elizabeth H. Berger Plaza via NYC Parks Department

But now, this tiny park will be part of a much larger 20,000-square-foot public space, the entirety of which will be dedicated to the literary legacy of Little Syria and provide a pedestrian connection between the 9/11 Memorial and Battery Park. The city will construct Elizabeth H. Berger Plaza, named for the Downtown Alliance’s late president Liz Berger, to honor the writers and poets from the historic enclave. Untapped reported earlier this week that the city chose France and Morocco-based artist and designer Sara Ouhaddou as the winner for the park’s public art monument. She’ll create “a stained glass dome resting on four thin tall pillars, with designs inspired by Arabic calligraphy.” The park is expected to be complete in 2019.

For more history, visit the Metropolitan College of New York, where their exhibit “Little Syria: An Immigrant Community’s Life and Legacy” is on view until March 24, 2017.

RELATED:

- Lincoln Center: From Dutch enclave and notorious San Juan Hill to a thriving cultural center

- Germantown NYC: Uncovering the German History of Yorkville

- The History of Herald Square: From Newspaper Headquarters to Retail Corridor

Historic images via Library of Congress unless otherwise noted