Before Repeal Day ended Prohibition in 1933: Speakeasies and medicinal whiskey were all the rage

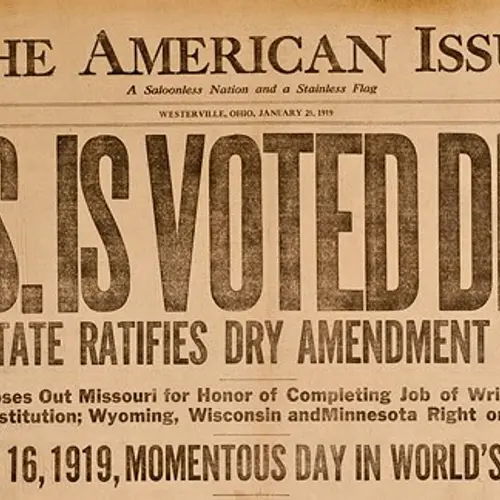

The last time a political outcome stunned the country with such a polarizing impact was in 1919, when the 18th amendment—prohibiting the production, sale, and distribution of alcohol—was ratified. After a 70-year campaign led by several groups known as The Drys, who insisted alcohol corrupted society, the ban on alcohol arrived in 1920 and was enforced by the Volstead Act.

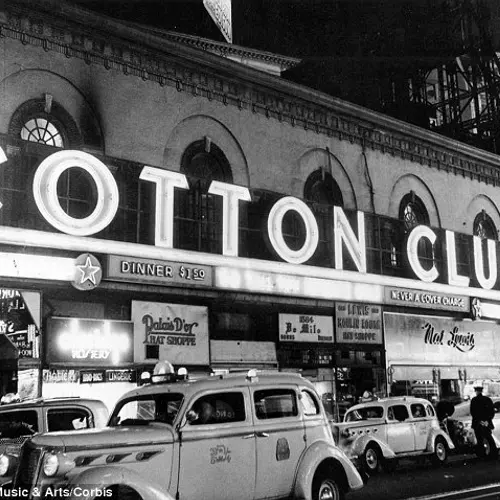

But the Noble Experiment did little to keep people from drinking. Indeed, Prohibition led citizens to dream up creative ways to circumvent the law, turning the ban into a profitable black market where mobsters, rum-runners, moonshiners, speakeasies, the invention of cocktails, and innovative ways to market alcohol took the country by storm. Prohibition in many ways fueled the roaring twenties, and it made things especially exciting in New York City.

December 5th marks the 83rd anniversary of Repeal Day, when 13 long years of Prohibition finally came to a close.

***

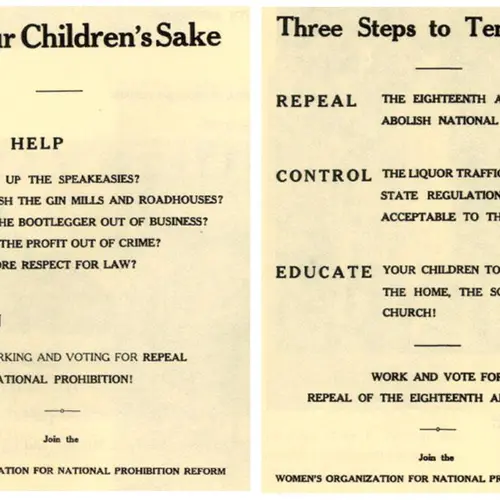

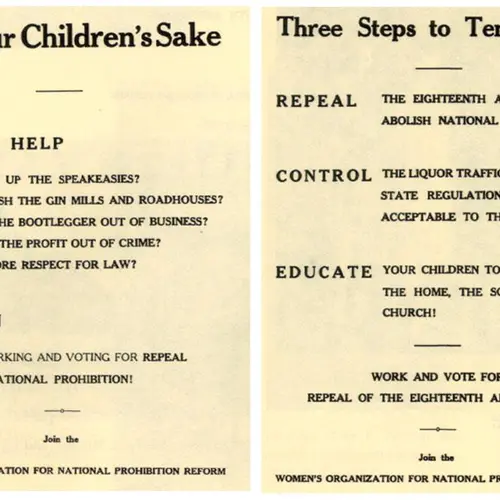

Groups like the Anti-Saloon League of America and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union were steadfast in their campaign to ban on alcohol, arguing that its consumption was “America’s national curse” and that it was destroying the values of the country. They also believed a ban would improve the economy because people would spend money on commercial goods and entertainment, rather than intoxicating elixirs. They also contended that a ban would reduce crime and protect women and children.

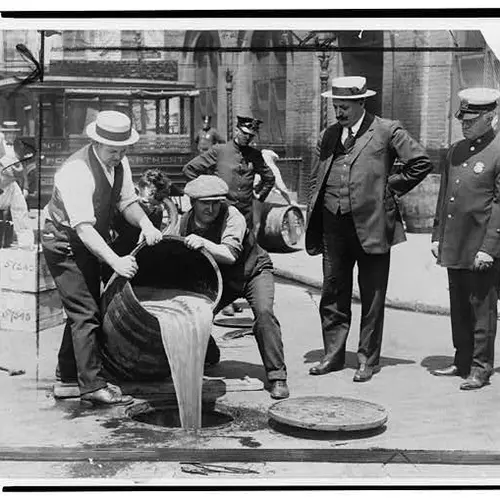

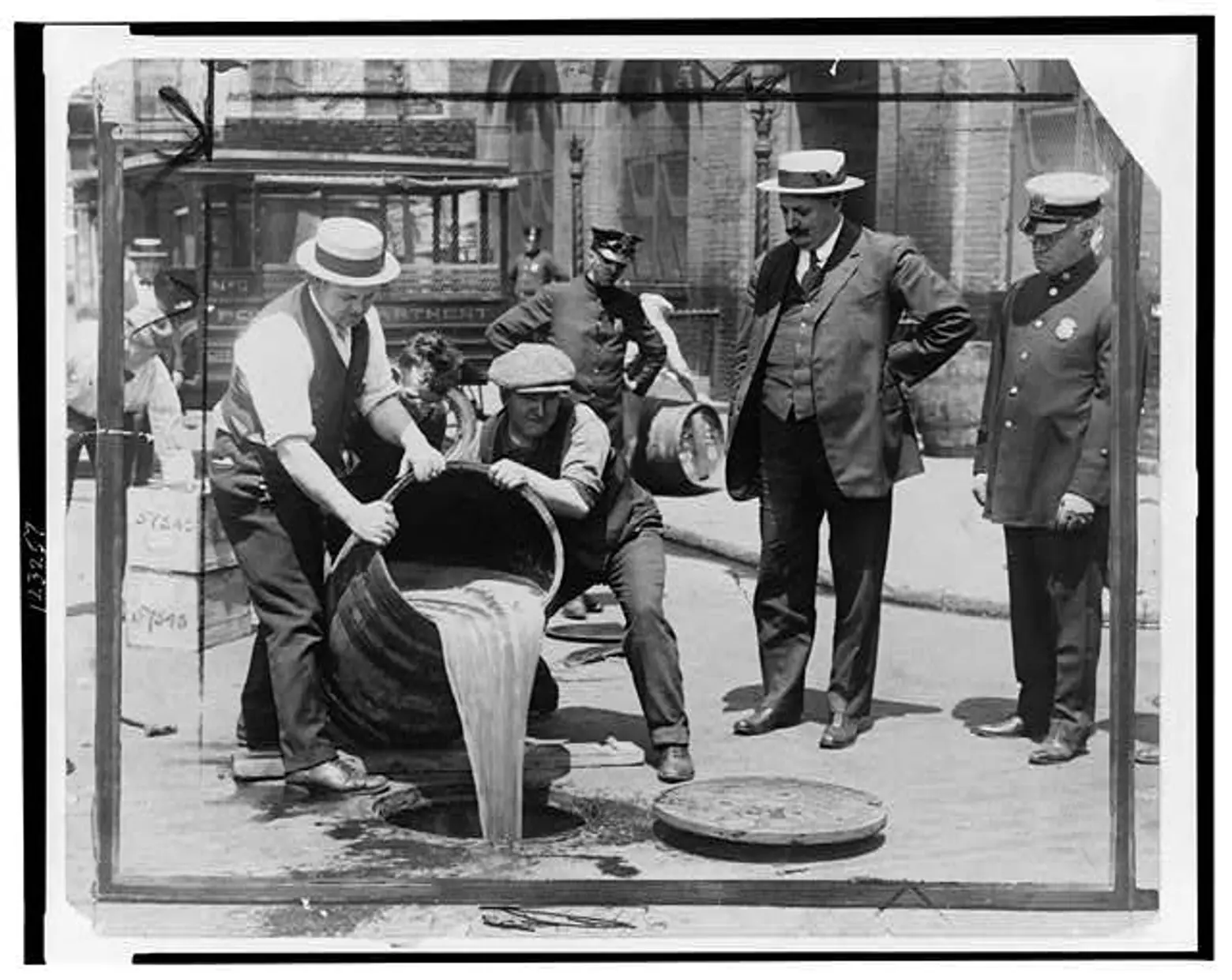

Confiscated alcohol getting poured into sewer in NYC, 1920 [All images from Library of Congress unless noted]

Confiscated alcohol getting poured into sewer in NYC, 1920 [All images from Library of Congress unless noted]

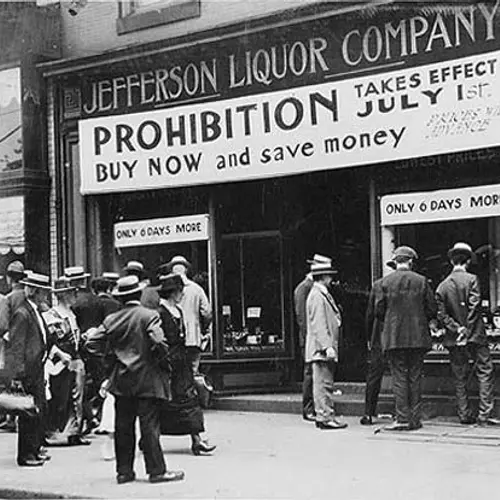

As soon as Prohibition began, saloons were closed and alcohol was confiscated and dumped into sewers and rivers. Barrels and bottles were smashed leaving shards of wood and glass in the liquid, rendering it useless while also preventing the containers from being used again.

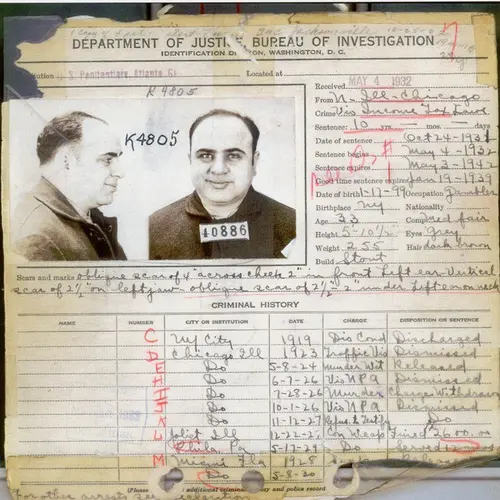

But moonshine and bootlegged alcohol quickly became a lucrative business after breweries and distilleries were shut down. The ban sparked organized crime across the country, and mobsters like the Brooklyn-born Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, Vito Genovese and Frank Costello took on transporting the product undercover. Trucks made with false exteriors were common, but unexpected bottle breakage would often lead to the discovery of the illegal libations. However, the risks of skirting the law came with a hefty profit margin; Al Capone made an estimated $60 million a year (or roughly $725M in 2016 dollars) from smuggling alcohol.

Truck with false exterior is confiscated for carrying alcohol

Truck with false exterior is confiscated for carrying alcohol

The invention of the mixed cocktail also emerged during this time as bootlegged liquor was of a lesser quality and often too harsh to drink straight. With that said, you can thank Prohibition for the Side Car, Bees Knees, Hanky Panky, South Side Fizz (a favorite of Al Capone), and the Corpse Reviver, which was intended to be a cure for hangovers.

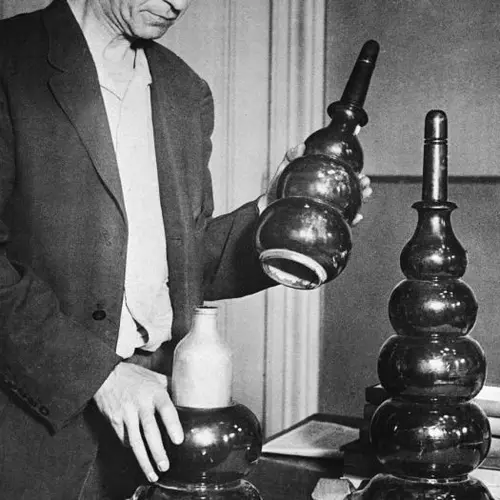

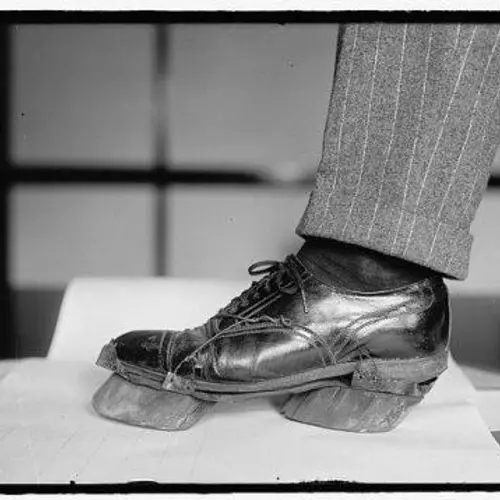

Hollowed cane used to hide alcohol during Prohibition, 1922

Hollowed cane used to hide alcohol during Prohibition, 1922

That same year, the 19th amendment was also passed, granting women the right to vote. The feminist ideal of the “New Woman” heralded in an era of liberation and freedom that shifted how women interacted socially and politically. The term New Woman was used for women who were educated, independent, and working toward a career, but also rebellious in their attitude toward social norms. As such, New Women and Prohibition were intertwined.

Flappers became a symbol of this period, and these young women were recognized for the bob haircuts and short skirts, as well as their unencumbered desire to explore their freedom through smoking, drinking in public, clothing, and visiting speakeasies. They were rebelling against the notion of social inequality, and illicit alcohol in an underground club seemed like a perfect choice.

Flapper clothing was also ideal during Prohibition because the flowing fabrics and flamboyant fur coats could easily hide flasks of alcohol. Women also used accessories like hollowed out canes to hide alcohol.

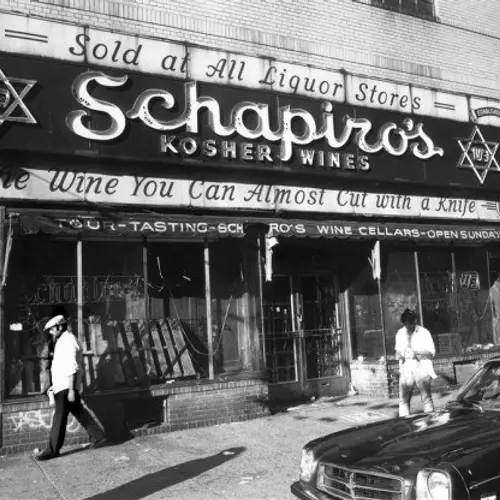

Kosher wine. Alcohol could still be used for religious purposes.

Kosher wine. Alcohol could still be used for religious purposes.

There were exceptions made for the ban and they were for religious, medicinal, and industrial alcohol. These, however, provided malleable loopholes in the law that opened the door for other markets of deception. For example, section 6 of the Volstead Act allowed Jewish families 10 gallons of kosher wine a year for religious use (the Catholic Church received a similar allowance), and as a result, sales for kosher wine skyrocketed as more and more people started to claim Judaism as their religion.

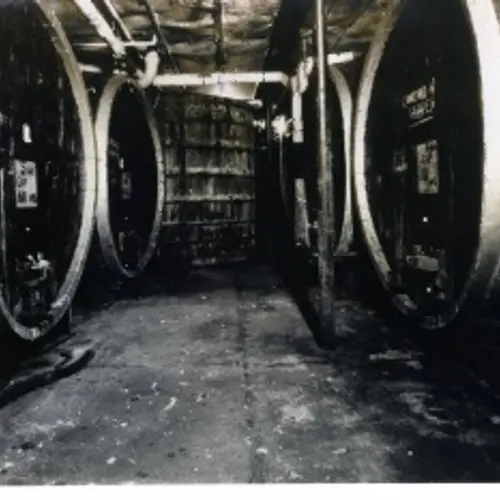

During Prohibition, Schapiro’s at 126 Rivington was allowed to stay open as a sacramental wine shop. Owned by Sam Schapiro, it was one of the most well-known kosher wine shops in New York, noted also for its trademark motto “wine so thick you can almost cut it with a knife.” Schapiro’s, however, had a less legit business humming away underground. The shop hosted a network of subterranean wineries running under several buildings and bootlegging higher proof alcohol. According to a New York Times interview with his Sam’s grandson, Norman Schapiro, the bootlegged alcohol was sold out the back door of the shop.

But Schapiro’s operations were pretty small beans when compared to some of the other dealings going on in other parts of the country. An article by Forward tells the story of Sam Bronfman, a Jewish Canadian who was the proprietor of a vast smuggling empire along the border of the United States and Canada. Bronfman bought up Joseph Seagram’s distillery and ferried products across water. He became so successful that Lake Erie became known as “the Jewish Lake.” Similarly, rum-runners took their name from the illegal trade of alcohol across waters, where rum was being brought over illegally from the Caribbean.

Whiskey enjoyed its own rebranding during this time and was designated for “medicinal purposes only.” Pharmacies vending the “medicine” began sprouting up everywhere, and bottles were adorned with instructional labels like “should be in every home for medicinal purposes” or “take this after every meal.” Some labels even directed its use with specific ailments like stomach aches or tooth pain. Similarly, hospitals were allowed to order cleaning alcohol, and despite the fact that it was in every practical sense rubbing alcohol, consumption was not uncommon if someone was hoping to get intoxicated.

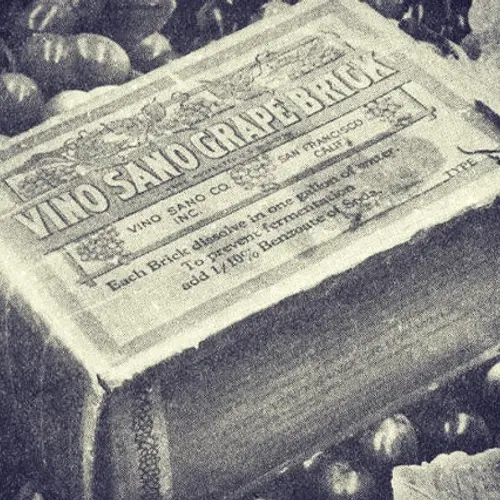

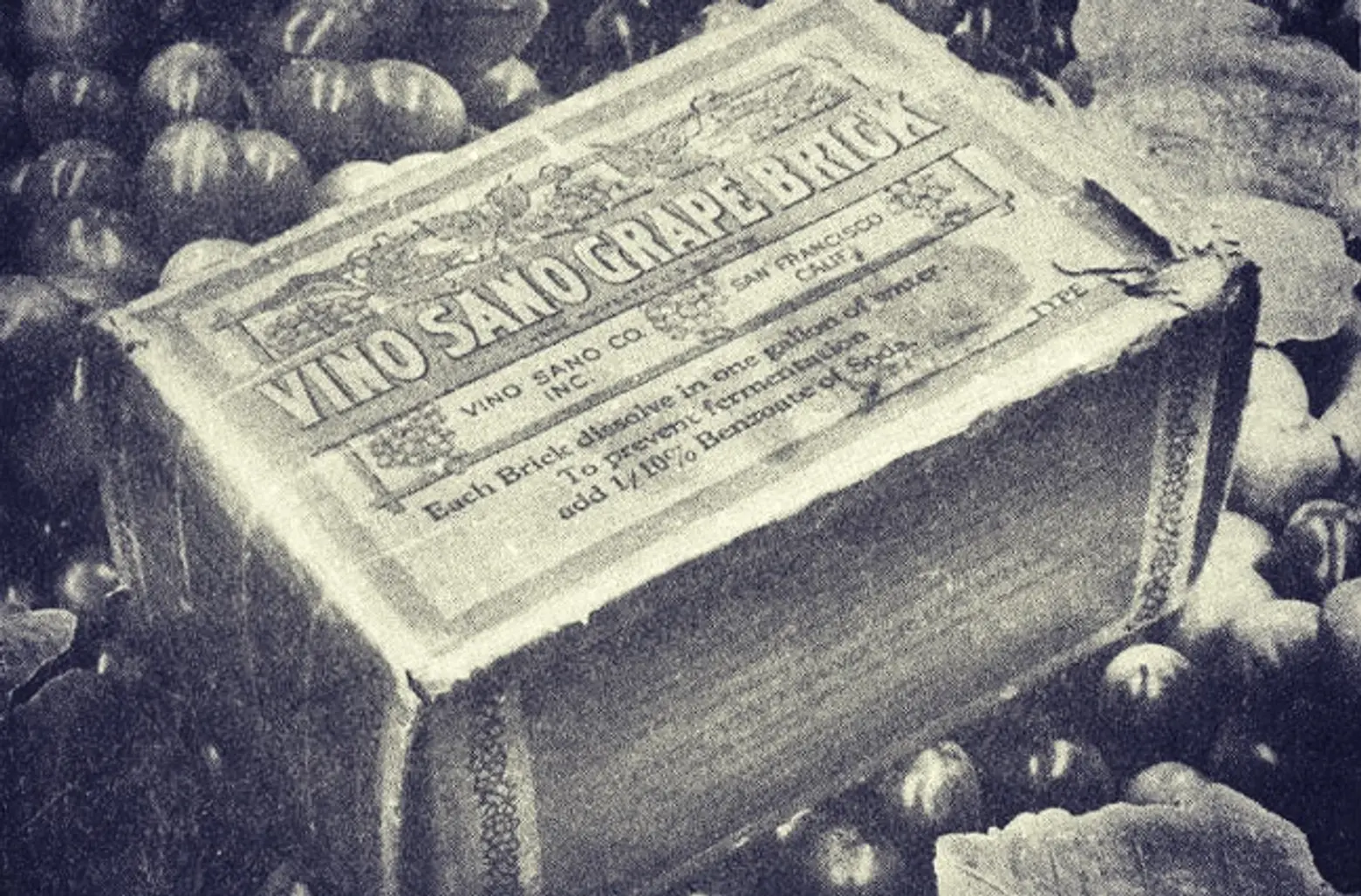

Another way around Prohibition laws – a grape brick used to make wine by adding water

Another way around Prohibition laws – a grape brick used to make wine by adding water

Grape growers, too, were reaping rewards from Prohibition after the grape brick was invented. The label stated “each brick dissolve in one gallon of water. To prevent fermentation, add 1-10% Benzoute of Soda,” more commonly known as sodium benzoate and used as a food preservative. The transparency of the label was obvious enough to direct people on how to make the instant wine, yet cautious enough to dodge Prohibition laws.

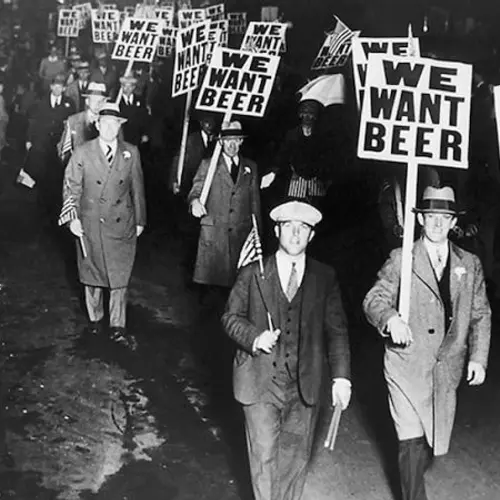

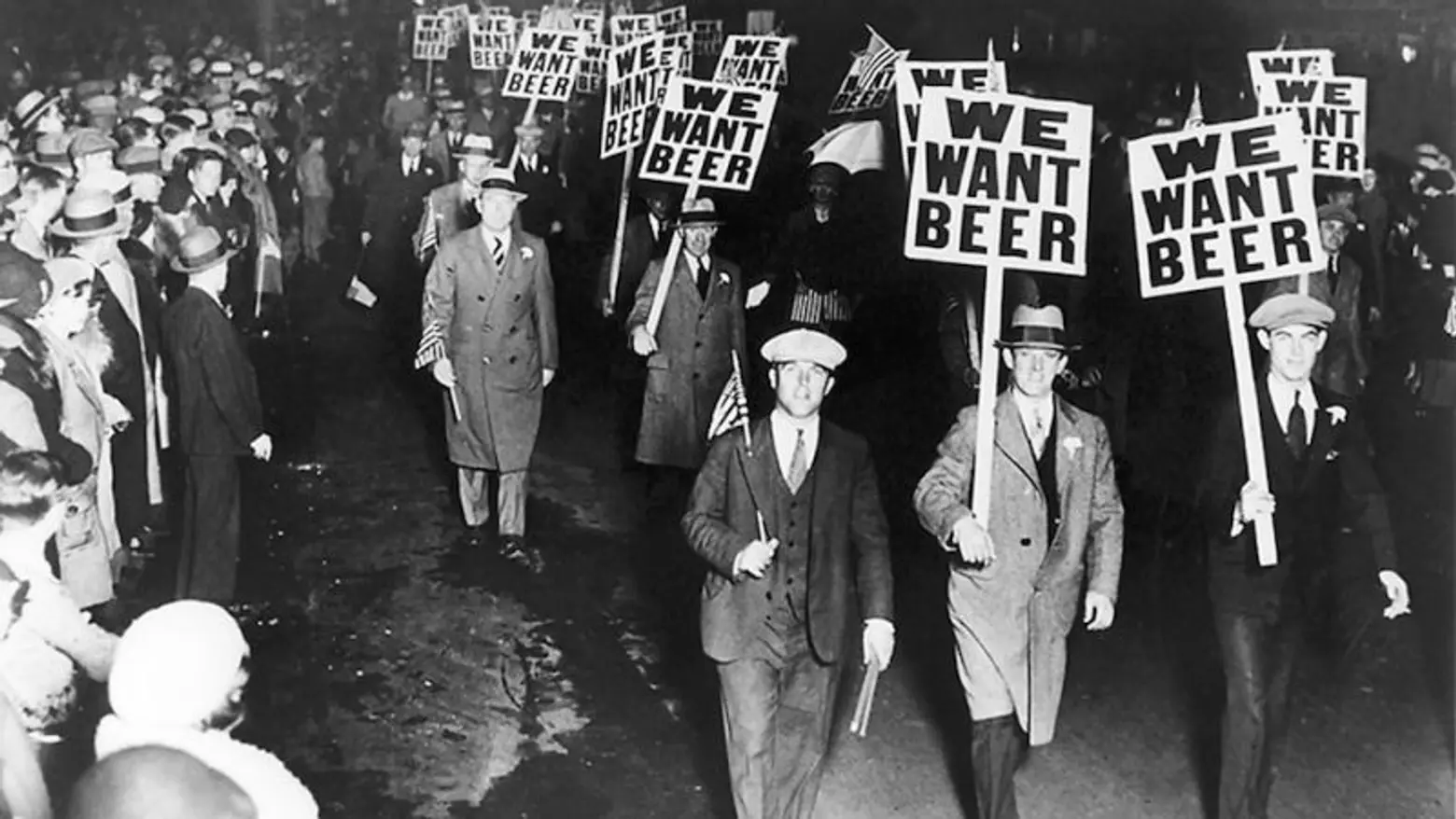

Beer Parade in Newark, NJ 1932

Beer Parade in Newark, NJ 1932

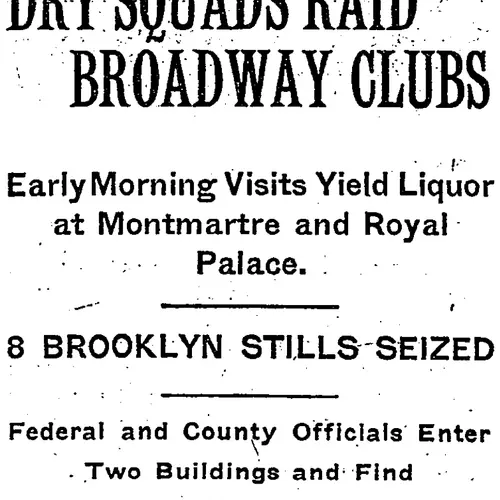

As Prohibition dragged on, it became clear the anticipated outcomes of the Noble Experiment were miscalculated. Crime increased during Prohibition because police officers often accepted bribes to look the other way. It also enticed law-abiding citizens with the possibility of financial prosperity through illegal sale or distribution. The Federal government lost and estimated $11 billion dollars in tax revenue from alcohol and ended up spending close to $300 million to enforce the ban.

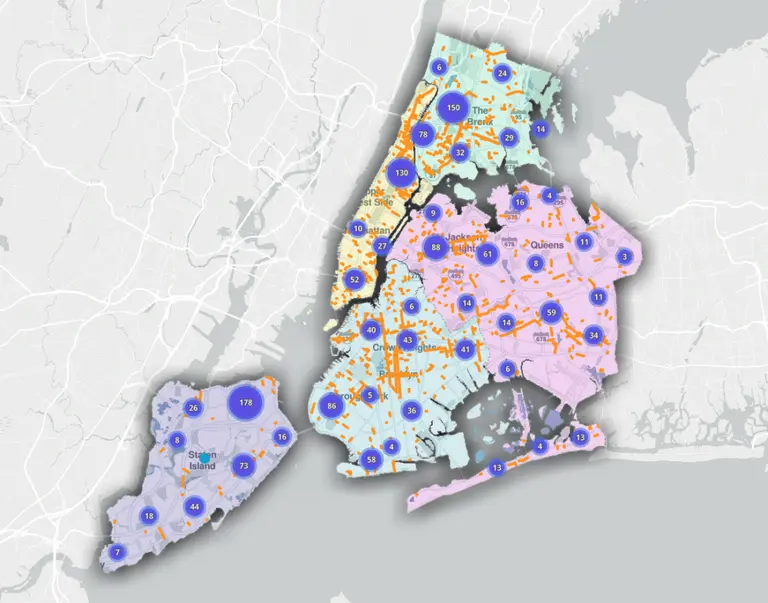

Ultimately, Prohibition was bad for the economy because jobs were lost in breweries, distilleries, and saloons. Restaurants closed because the ban on serving alcohol drastically reduced profits, and Federal and local governments were spending massive amounts to maintain the law. Once home to the most breweries in the country, the brewing industry in Brooklyn never fully recovered after Prohibition was repealed. The New York Times reported that 70 breweries were operating in New York and produced 10 percent of the beer in the country before Prohibition, but only 23 remained by the time it was repealed. Although other economies (smuggling, speakeasy proprietors, bootlegging) developed during the 13-year dry spell, they could only exist during Prohibition and were not sustainable once it ended.

Innovation reappeared in protests against Prohibition and they were focused on a message that beer should be legal because the taxes would improve the economy. On December 5, 1933, the 18th amendment was repealed by the 21st amendment—the only time an amendment has been repealed through another amendment.

Today, speakeasy-themed bars are common around city, but they speak more to novelty than anything else—who can argue the appeal of passing through secret doors to reach a hidden back room bar few know about? These bars also let people believe for a few hours that life was more glamorous and exhilarating in the roaring twenties.

But we’ll leave you with this: Next time you hear last call for alcohol, be grateful it only means eight hours rather than 13 years.

RELATED:

- Pinball Prohibition: the game was illegal in New York for over 30 years

- East Village speakeasy turned condo building has four bedroom duplex up for rent

- 5 Prohibition-Style Speakeasies to Transport You Back to the Gilded Age

- Spotlight: The word on whiskey from King’s County distillery’s Colin Spoelman