27,000 Tons of Floating Concrete and Fabulous Feats of Engineering Make Pier 57 Peerless

In the summer of 1952, when the American economy was emerging with a roar from the stagnation of the Great Depression and World War II, engineer Emil H. Praeger was chosen to create a replacement for the Grace Line’s old Pier 57 which had been destroyed by fire. Described by the New York Times, the key to what makes the resulting replacement pier so special lies hidden below the pier shed in the Hudson River at the foot of West 15th Street; Rather than resting on a conventional pile field, the bulk of its weight is held up by three floating concrete boxes known as caissons, which are permanently anchored underwater.

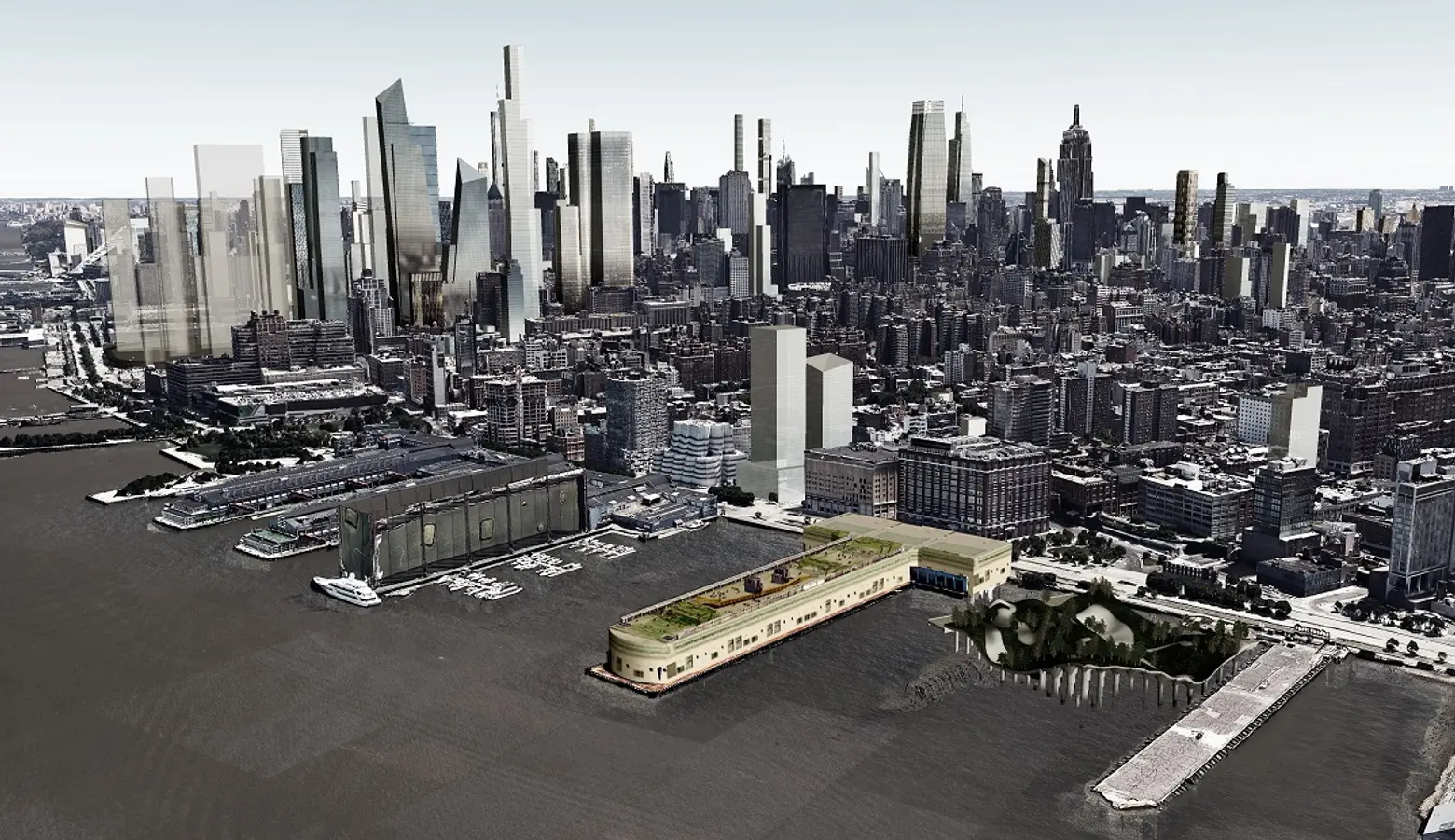

The unique foundation of the abandoned pier is the same foundation that will host a $350 million renovation of what is being called the SuperPier by RXR Realty and Youngwoo and Associates, thanks to a lease from the Hudson River Park Trust, with new tenants to include Google offices and Anthony Bourdain’s new food market.

The Times takes a trip down a set of underwater stairs (!) to take a look at this revolutionary construction feat, which apparently hasn’t been put into use before or since and has earned Pier 57 a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. Praeger had helped build floating concrete caissons used in the construction of artificial harbors on the coast of France during World War II; he designed Pier 57 using the same idea.

The caissons were fabricated 38 miles up the Hudson on an an artificial riverfront basin with the water drained out during their construction. Two caissons made to support the pier shed weighed 27,000 tons each. A smaller caisson was designed to support the pier’s perpendicular head house, with the two parts making a T shape. When the caissons were finished, water was sent back into the basin.

So how do these things float? The Times quotes Guy Nordenson, a professor of architecture and structural engineering at Princeton University: “Buoyancy is an upward force equal to the weight of the water an object displaces.” Though solid concrete would sink, the caissons are hollow. Though the large ones weigh 27,000 tons, they displace much more than their own weight, about 47,000 tons of water. The density of the caissons’ total volume of air and concrete is less than the density of the equal volume of water.

Possessing less engineering savvy, local residents were amazed that summer in 1952 when the heavy “cheesebox-shape” structure was hauled out into the river by six tugboats on its way to the city. Dedicated in 1954, the pier is still the only known example of this kind of construction.

Madelyn Wils, president and chief executive of the Hudson River Park Trust, raised the valid point that Pier 57 would likely would remain one-of-a-kind. “The regulatory agencies would never let you displace so much water,” she said. “So it could never happen again.”

This remarkable underground square footage courtesy of Mr. Praeger won’t go unutilized in the new life planned for Pier 57. “The caissons will have accessory parking and storage, and we hope to lease them,” according to Seth W. Pinsky of RXR Realty, mentioning art galleries or retail as possibilities as well.

[Via NYT]

RELATED:

- New Renderings of SuperPier: Google’s New NYC Digs + Bourdain Food Market To Arrive in 2018

- Google Officially Signs Lease for 250,000 Square Feet at SuperPier

- Pier55 Floating Park Gets New Renderings and Updated Design Details

Renderings courtesy of Young Woo & Associates, RXR Realty.