Spotlight: Climate Scientist Radley Horton Discusses Extreme Weather in NYC

With increasing concerns about rising sea levels and the large quantity of greenhouse gas emitted into the atmosphere, Radley Horton‘s work is more important than ever. As a climate scientist at Columbia University, he’s working on the applied end of climate change by examining data to make projections about the possibility of extreme weather events. Based on the data and ensuing models, he then considers the impacts these potential events and the overall changing climate might have in a variety of contexts that range from airports to the migration of pests. Radley is on the forefront of understanding what might happen and how cities, countries, and other entities can prepare even in the face of uncertainty.

6sqft recently spoke with Radley about his work, areas of climate concern in New York, and what we all can do to combat a changing planet.

What drew you to earth and environmental science?

From a very young age I was interested in numbers and, more specifically, extremes. I can remember pouring through old almanacs that talked about minimum temperatures in far away places like Siberia. After college, I started to appreciate how important interdisciplinary work was, but when I was trying to decide about going back to graduate school, I realized you have to specialize. I remember picking climate in part because it was quantitative and I thought if I didn’t stay with it, I’d at least have a quantitative background.

I had absolutely no idea the extent to which climate science would provide a window for me to learn about the world and all these interesting systems ranging from the responsibilities of the people who run the subways to the concerns of water managers. As an applied climate scientist you learn a lot about other cultures because everything is affected by climate.

What is your research focused on right now?

I’m most interested in extreme events. This is everything from heat waves to cold air outbreaks to heavy rain events. I’m also very interested in the idea that while climate models are our best tool for predicting the future, what if they’re only giving us part of the picture about what might happen in the future? I’m mostly looking at existing data, outputs from climate models, and then using that information to try to make regional projections for things like sea level rise and future heat waves. We also try to assess what the impacts of those climate extremes are going to be. [For example], right now we’re working on how ecological pests like the southern pine beetle are limited by really cold winter temperatures. I’m also interested in how airplane runways may not be long enough in the future as temperatures go up and it’s harder for an airplane to get lift.

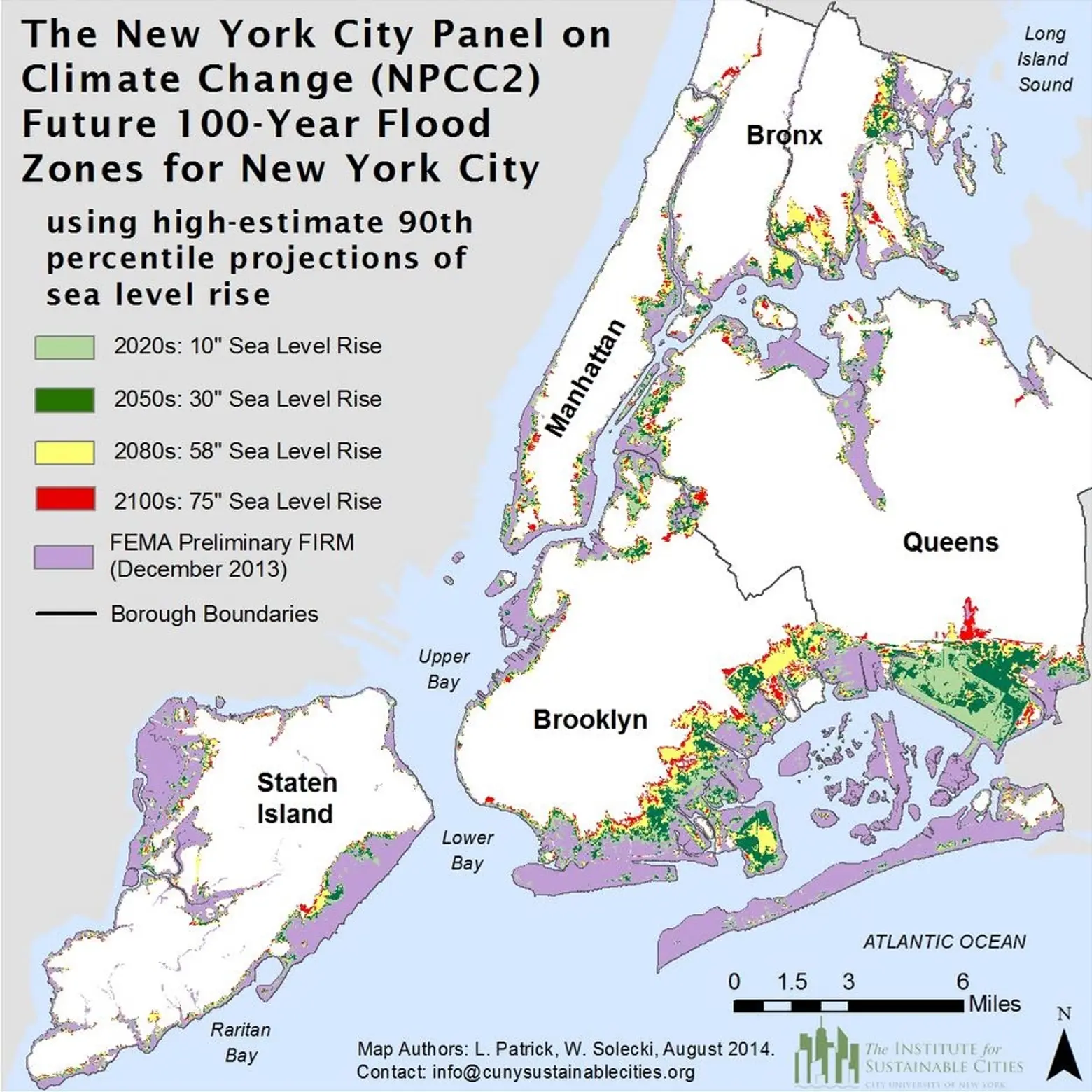

The climate change map released in 2015 by the New York City Panel on Climate Change

Where does New York fit in with your work?

I lead a project called the Consortium for Climate Risk in the Urban Northeast, which is focused on the three major cities—Philadelphia, New York and Boston. We’re exploring how these cities are vulnerable to climate extremes and how they can prepare for higher sea levels, frequent coastal flooding, and more heat waves in the future.

What are the biggest climate threats to the city right now?

Sea level rise and coastal flooding. As sea levels rise, storms even weaker than Hurricane Sandy will be able to give us just as much coastal flooding. New York City’s also very concerned about heat waves. There’s a lot of emerging research showing that heat waves may be our most deadly weather disaster, and that hasn’t always been appreciated by the public. Some of the ways that heat waves kill are more subtle. They strike people who have preexisting health conditions, heart conditions, or respiratory conditions. And it doesn’t necessarily show up at a hospital visit.

How is the city starting to put this information into action?

The city has convened a task force, which spans across many government agencies, planning bodies and the private sector to assess what the vulnerabilities are and to take steps to prepare. There’s a wastewater treatment plant on Coney Island that elevates critical equipment to prepare for sea level rise. In terms of preparing at the building level for coastal storms and flooding post-Sandy, a lot of buildings have moved their critical equipment such as generators up to higher floors in the buildings, and there are plans to accommodate the water on the ground floor of some buildings being designed for the future.

We’re also seeing construction of coastal barriers to help when there’s flooding and more of what’s called green infrastructure around the city. This means adding natural vegetation and removing all the pavement, so if there’s a heavy rain event or a storm surge, some of that water can be captured by the vegetation to reduce flooding. In terms of heat events, we’re adding heat wave warning systems and more cooling centers and helping get air conditioner systems to the poor.

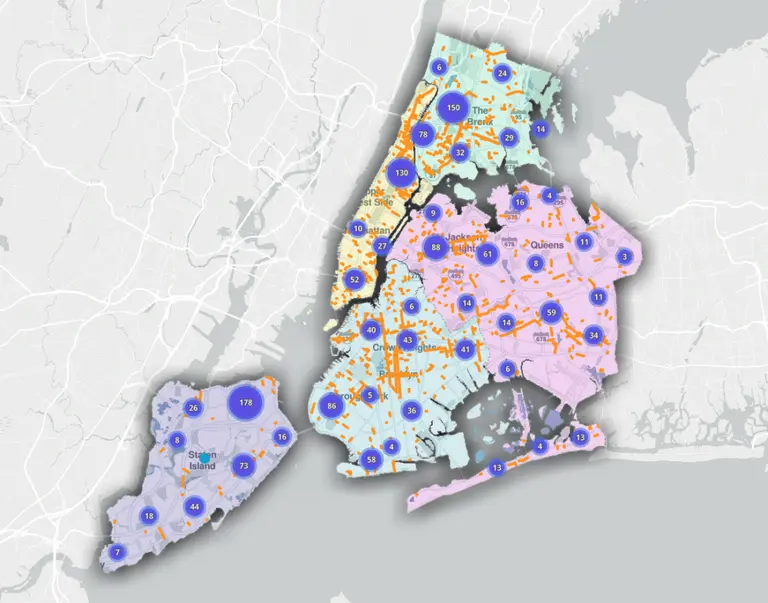

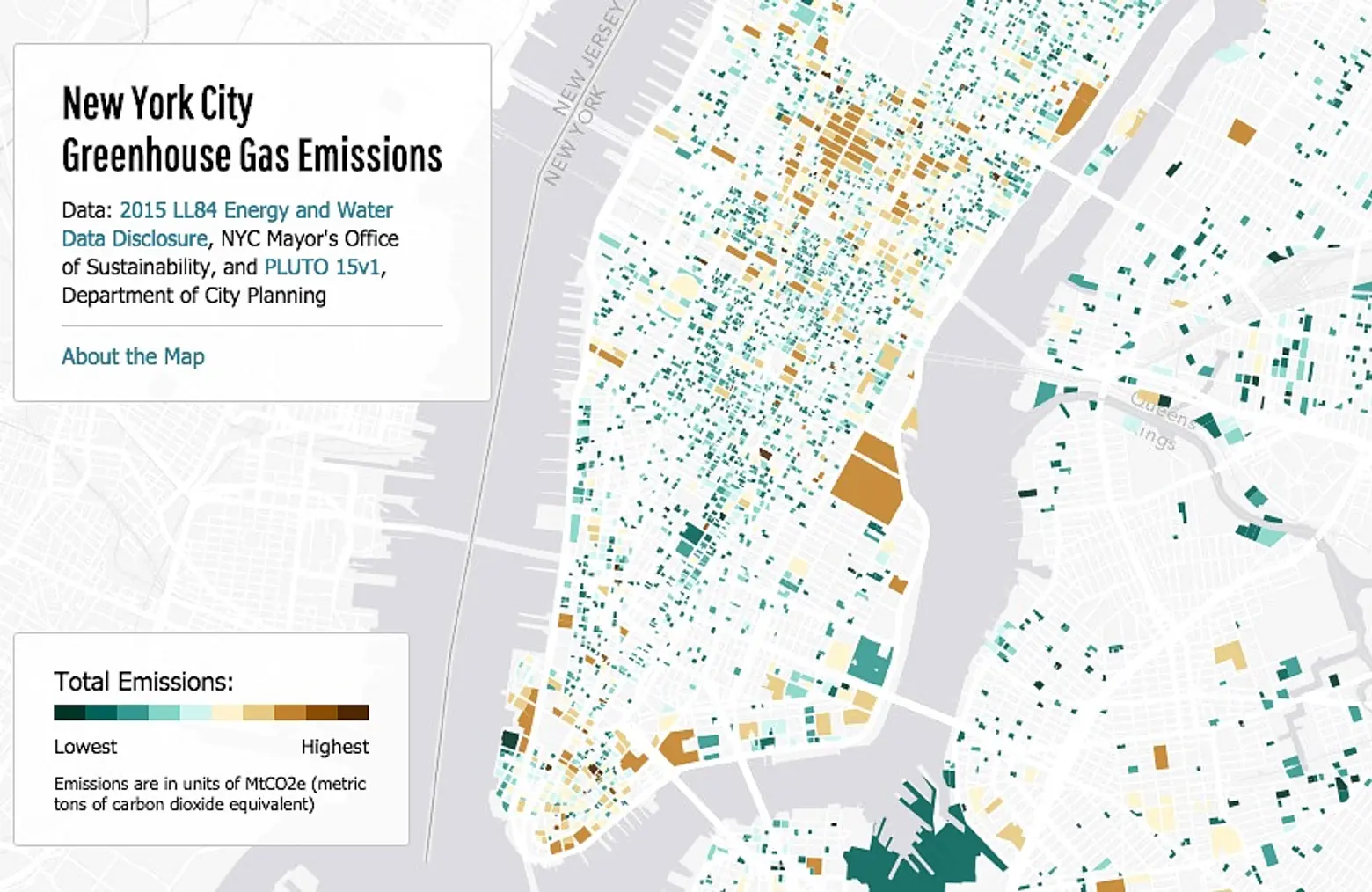

A map from Brooklyn web developer Jill Hubley that shows the greenhouse gas emissions of NYC buildings

Are there additional policies that need to be enacted to protect the city?

One of the challenges is that greenhouse gas concentrations are still increasing globally. Even though New York City and New York State are trying to reduce their emissions, we’re locked into additional sea level rise and increases in the frequency and intensity of heat waves. In the worst case scenario, we could see sea levels rise six feet or more by the end of the century. Here in New York City, six feet of sea level rise would mean what’s currently a one in 100 year coastal flood is something that could be experienced every decade or so.

Even if you protect the city, can you protect all the vulnerable populations and infrastructure surrounding it? What if the surrounding communities, if the rest of the East Coast, are seeing failure of flood insurance programs? What happens to our roads, I-95, our Amtrak? The city is doing so much, but we need national and international leadership both to adapt and most fundamentally to dramatically reduce our emissions of greenhouse gas to try to avoid the worst outcomes.

While there are more green buildings going up, what impact does New York’s constant construction have on the environment?

It’s very important to think about the lifecycle of energy costs associated with everything, including construction. It’s not just about fossil fuels that you burn heating that building. When we think about cities on the one hand, the per capita greenhouse gas emissions can be better than the countryside because people tend to drive less and housing units tend to be connected to other housing units so it doesn’t require as much energy to heat and cool. On the other hand, construction is by definition an energy intensive process, and while we’ve seen a lot of move towards more efficient buildings, on some level, I’d say we need to as a society decrease our greenhouse gas emissions by 80 or 90% probably if not more.

What are some of the ways society can do this?

We need to shift away from coal, oil and ultimately natural gas towards more renewable energy sources. We’re going to need emerging technology. The private sector is going to play a critical role for things like battery storage and new electrical grids.

We also need to think hard about resilience and protecting the most vulnerable countries around the world whether it’s Ireland and highly populated Delta cities threatened by sea level rise or parts of Africa where people are living at the margins in terms of food security and water availability. A little bit of warming could push a lot of those communities over the edge.

Via Columbia University

With all of this uncertainty, what concerns you most about climate change?

It’s ironic because a lot of climate skeptics spend so much time saying, “Oh, we shouldn’t trust these climate models. They’re just models.” Even though models are our best tools, what if we were wrong in the other direction? What if we’re on a path to some climate surprises, positive feedback things where once they happen, they actually accelerate the warming. A classic example is the issue of sea ice. We’ve lost over half of the sea ice we used to have in the Arctic Ocean in late summer in just the last three or four decades. No climate models predicted that that would happen so fast.

I believe it’s raised the prospect that we could essentially have an ice-free summer in the arctic any year now, and I think it’s not well appreciated by the public or the scientific community. But nobody really knows for sure exactly what’s going to happen the following fall and winter after we have that ice-free summer. So I can’t tell you if it’s going to be next year or 20 years from now, but I’m concerned that parts of the climate may be more sensitive than we realized and once we see some of these big changes, they’re going to be more surprises in store for us.

+++

[This interview has been edited for clarity]

RELATED:

- Mapping the Greenhouse Gas Emissions of NYC Buildings

- In 2080 NYC Will Be Hotter, Rainier, and 39 Inches Underwater

- What Would NYC Look Like If Sea Levels Rose 100 Feet?

- More Green Buildings Likely Under NYC’s New Greenhouse Gas Plan

Lead headshot via Radley Horton