Safer and Smaller Crane Could Cut Building Costs by Millions, But the City Doesn’t Allow Use

The Skypicker in use, via JOMAC

Crane safety has made major headlines in recent months, after a crane collapse in February killed a passerby in Tribeca and reports surfaced about an uptick in construction site deaths. But at the start of the city’s current building boom, there was a man and a crane who sought to make skyscraper construction safer, not to mention quicker and cheaper.

Crain’s introduces Dan Mooney, president of crane leasing company Vertikal Solutions and designer of the Skypicker, a lightweight mobile crane. It’s only 10-feet tall with a 30-foot boom (compared with tower cranes that rise hundreds of feet), but Mooney says that’s the point, that it “can fit in small spaces and is ideal for midsize buildings where tower cranes are overkill and mobile cranes or derricks are not big enough.” When it was employed in 2012 for Midtown’s Hilton Garden Inn, the 34-story building went up in just six months. After that, Mooney’s phone was ringing off the hook with developers looking to save time and money on smaller projects, and he had four more Skypickers built. So why are they now sitting idle in a warehouse in Astoria?

Mooney, who worked for decades as a non-union crane operator, had long been concerned about tower cranes’ jump cycles — “when the top of a tower crane is jacked up briefly on hydraulic lifts so a new section of steel tower can be secured to increase the machine’s height.” He worried about the exact precision and weather conditions needed for this. And in 2008, when two tower cranes collapsed after failing in the jump cycle and killing seven people, Mooney started on his own design, which as Crain’s described:

…took a telescoping boom that might normally be mounted on the back of a truck and placed it on a column that could run through a 16-inch hole set near the edge of the concrete floors of a new building. To move from one floor to the next, the crane is jacked up on hydraulics, then secured on the next floor with a collar. With the crane bolted to the floor, its boom hangs over the edge of a building and raises and lowers cargo from the street using steel cables.

The Department of Buildings approved his design in 2012, and two months later he was at work at the Hilton Garden Inn. But when faced with pressure from the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 14-14B, who represent the city’s tower crane operators (and were, by some reports, placing phony 311 complaints), the DOB reneged. These union employees make up to $150,000 annually, before overtime and factoring in benefits, which could bump it up to almost half a million. The local decides who gets hired and trained (and gets an operating license) and what types of cranes and workers are needed on a job site, therefore dictating how and when new towers can be constructed.

The DOB’s reversal leaves smaller buildings to be constructed with tower cranes, a situation that Mooney says isn’t economical or safe. Not only are there the high labor costs, but insurance premiums for jobs using a tower crane can surpass $1 million, based on location and the company’s revenue and accident history. These prices skyrocketed after the 2008 collapses, with the city increasing the required general liability insurance on a tower crane project from $10 million to $80 million, whereas the Skypicker wraps insurance into the construction sites’ general liability coverage. Additionally, the total cost per month to rent a Skypicker is about $40,000, compared to $100,000 for a tower crane before insurance and labor.

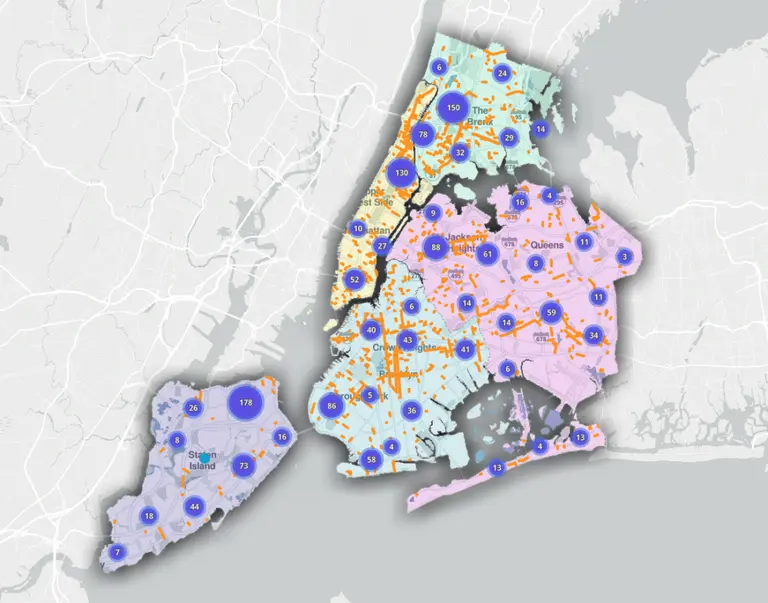

Since 2008, 39 buildings between 20 and 35 stories have broken ground, and often they’re made of reinforced concrete, “perfect for the three-ton lifting capability of a Skypicker.” But for the cranes to come out of their Astoria warehouse, they’d need to go through the entire approval process again, and under de Blasio’s DOB leadership, this means doing everything as a tower crane would, creating an entirely new prototype, and having to carry increased insurance. “I sunk a million dollars of my own money into this. I did it for the city,” said Mooney, adding that he might fare better waiting for a new administration in 2017.

[Via Crain’s]

RELATED: