INTERVIEW: The Museum of Food and Drink’s Peter Kim Talks Food and Preservation

This past October, the Museum of Food and Drink opened its first brick-and-mortar space in Williamsburg. Known as the MOFAD Lab, it’s a design studio where the team is currently creating and displaying their exhibition ideas, as well as surprising a city who may have likened a food museum to merely big-name chefs and of-the-moment trends like rainbow bagels. Take for example their first exhibit “Flavor: Making It and Faking It,” an in-depth and multi-sensory exploration of the $25 billion flavor simulation industry. Two more refreshingly unexpected facts are the background of executive director Peter Kim (he previously worked in public health, hunger policy, and law, to name a few fields) and the museum’s first home at the Neighborhood Preservation Center (NPC), an office space and resource center for those working to improve and protect neighborhoods.

If you’re wondering what preservation and a food and drink museum have to do with each other, 6sqft recently attended an NPC event at MOFAD Lab to find out. After chatting with Peter and NPC’s executive director Felicia Mayro, we quickly realized that the two fields have a lot more in common than you might think. Keep reading for our interview ahead, and if you want to visit MOFAD LAB, enter our latest giveaway. Peter is giving a lucky 6sqft reader and a guest free admission to the museum (enter here).

6sqft: Peter, why don’t we start off with you talking a bit about how the museum came to be and how you got involved?

Peter: There’s a food innovator and author named Dave Arnold, and he’d actually had the idea kicking around in his head since 2004. Back then he was still a budding figure in the food world, but he had this uncanny ability to draw connections between seemingly disparate subject matters and linking it through food. So it was striking to him that there wasn’t a food museum that took this sort of multidisciplinary approach. There are actually a lot of food museums out there in the world, but most of them take a collections-based or historical approach, and they tend to be very small and focus on something that’s specific to their region.

By 2011, Dave was thinking of something much bigger. I went to an event that he put together and met him, and we hit it off. It connected all of these interests I had and also an interest on my part to do something that was educational but also really took a non-didactic approach to things. The more we spoke about the project, the more we realized we were on the same wavelength for what a museum like this should look like, which I think was a really fortunate coincidence because there are so many ways a museum like this could go. So suffice it to say, I started helping him work on the project. And then in 2012, I decided to take the leap and make it a full time pursuit. And that’s when I met Felicia.

6sqft: That leads right into my next question. The museum began in the basement of the Neighborhood Preservation Center, which has certain guidelines for what kinds of organizations can operate in their space. How did both of you come to realize that preservation and food were a fit?

Felicia: When Peter came to look at the space and talked about the vision and mission of the museum, it just seemed natural. We had previously organized a panel discussion on local food, and we already had community garden groups using the space at NPC so there was an environmental angle. But there also was the cultural piece. Just as you might celebrate somewhere like Russ & Daughters, its food, culture and, history is absolutely a part. It has that essence of a place and a history.

Peter: Preservation is at the heart of our mission. I think it’s difficult to even talk about food culture or the industrial food system or food science without looking at history. And when you’re looking at history, there’s inherently a need to preserve so you can learn from it. I think this exhibition [Flavor: Making It and Faking It] is a great example. It’s very science focused, but we still have artifacts because you can’t tell the story of the modern flavor industry without getting into the history.

You can also see history in food very easily. I think a great example is if you go into a Trinidadian restaurant, every menu item reflects the waves of immigration that came through Trinidad. You originally had indigenous people, of course, and then you had European explorers, and black slaves. After the abolition of slavery, you had Chinese and Indian laborers who came in to replace the slaves. As a result, Trinidad has a cuisine that is remarkably cosmopolitan and has influences from China as much as it does from Africa, as well as clear Indian influences. You have aloo pies that have spinach curry inside of them. In New York City, if you go to Wo Hop in Chinatown or up to Mission Chinese, you’re seeing the evolution of New York City through the food.

6sqft: Is it difficult to make this case, that food is part of culture?

Peter: It’s something that we always have to make clear from the outset, but I would say that it has not been so challenging, and that’s part of the reason why the time is really ripe for something like this. Five or ten years ago it might have been a more difficult case to make. Now, you have food studies departments in many major universities. Every major periodical has their food issue once a year. You have policy advisors who are focused primarily on food. So I think people are more receptive to the notion of food being something that goes beyond just culinary arts or something that’s purely about sustenance or pleasure.

6sqft: Speaking of the time being ripe, how do you feel about this whole changing food scene? Do you think it’s representative of how the city as a whole is shifting?

Peter: Even if the term didn’t exist historically, I think New York has always been a city of foodies. Look at the history of Chinese-American food. It really got its start in New York, whereas toward the end of the 19th century, most people viewed Chinese food as sort of dangerous, unsafe, of a dubious origin, and not to mention a lot of racist beliefs about Chinese people at the time. But there were still these bohemian slummers who were exploring the city and eager to try new flavors and exotic cuisines. And so it was really in the late 19th century that these slummers went to Chinatown and started going into these places that were meant for a Chinese clientele and trying things like chop suey. When they deemed it cool, it became this huge fad. By 1920 you had people all around the country throwing chop suey parties. Many of the chop suey restaurants in New York City were not even in Chinatown, but in Midtown or Upper West Side. That’s a story you could imagine happening today with somebody finding the ramen burger and then everybody following suit.

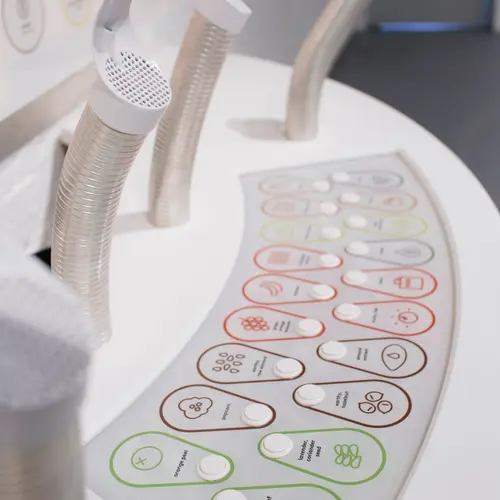

MOFAD’s one-of-a-kind “smell synth”

6sqft: There’s so many more vehicles for people now to experience food culture now. You have places like Smorgasburg where you can go to one place and try food from 20 different countries; you don’t even have to travel anymore.

Peter: I think that’s what’s changing and what I hope for MOFAD to be a part of. It’s more of an interest in having a meaningful engagement with food and understanding the stories behind it. I’d say we’re a part of a larger shift of trying to understand that when you order a dish, there are workers who made it and they’re part of an economic system. There are ingredients that were grown somewhere, there was breeding that went into creating those fruits and vegetables, there were people who were picked it who are getting paid a certain amount, there are transport systems. There’s flavorists adjusting the flavor of the food, there’s regulations that come into play, there’s science that’s happening in the kitchen when you’re cooking. There’s an effect on the environment, there’s an effect on your health, there’s an effect on the community. And so seeing all those criss-crossing connections, that’s really I think where MOFAD is trying to like push things.

6sqft: You can probably say a lot of the same things about physical buildings. People who aren’t so involved in architecture and design might not think about the structural components of a building or the ornamentation that comes from a specific culture.

Felicia: Oh yes, of course. For instance, there are these churches in the Philippines from the Spanish colonial period. The galleon route to the Philippines from Spain was through Latin America, so these churches have Spanish and Latin American architectural features, but they also frequently have motifs and details added by the builders themselves, so, for example, you might see a Chinese motif on the exterior wall. The final structure is ultimately Filipino.

Peter: If you think about what makes a neighborhood a neighborhood, food is so central. When I think about the East Village where I live, I think Japanese, I think Filipino, I think Ukrainian, Polish. There was a time when the neighborhood would have been thought of as predominantly Ukrainian or Polish, and it would have been unthinkable for it to be Japanese, but the neighborhood changes.

6sqft: Brooklyn, and specifically Williamsburg, are epicenters of the foodie revolution. Was choosing this area as a location intentional? And has it helped you?

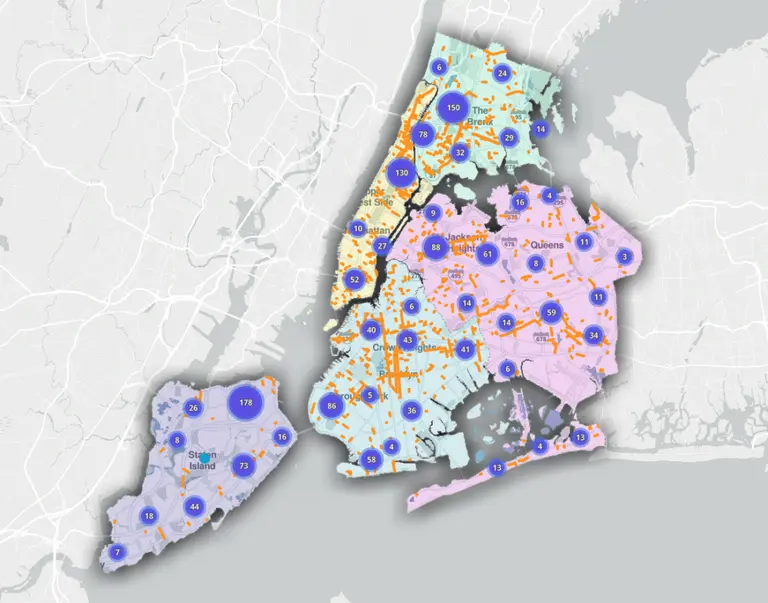

Peter: I think frankly a lot of places in the city would work well, but what I like about Williamsburg and Greenpoint in particular is that there’s the “foodie” side, but it’s a neighborhood that is incredibly multicultural. You have an Italian community, you have a Polish community, you’ve got Dominicans, and then you have of course the newer wave of people coming in. And I think it all comes together to make for a really interesting tapestry of food cultures. I think New York City in general, in my humble estimation, is the best place in the world for a museum like this because there are not really other cities where you have so many different cultures colliding and interacting and having their identities expressed through food.

6sqft: Let’s end on a note about your personal histories. Is there a particular food or food-related memory from growing up that really sticks with you? Perhaps a comfort food?

Felicia: My grandmother was an amazing cook. She would always make Filipino food, especially when my mother and father would have dinner parties. What I really remember is sitting with her while she made leche flan. She had this big double boiler, and my job was to help crack the eggs and divide them. I just wish I paid more attention.

Peter: When you talk about your grandma, I think about my grandma too, and her making dumplings. I was always mesmerized watching her make them. But I grew up in the Midwest, and the first thing that came to my mind when you said comfort food was mac and cheese. I actually ranked my family members based on how they made mac and cheese. My mom would just put milk with no butter. And my brother would put a little bit of butter. But my grandma would just hack into the butter stick and drop it in. And so my grandma made the best mac and cheese.

+++

Enter to win two tickets to the MOFAD Lab here >>

MOFAD Lab

62 Bayard Street

Brooklyn, NY 11222

RELATED:

- INTERVIEW: Andrew Berman, Executive Director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

- New Yorker Spotlight: Lee Schrager Unites the Culinary World at the NYC Wine & Food Festival

- INTERVIEW: Captain Jonathan Boulware Sets Sail as the South Street Seaport Museum’s Executive Director

All photos courtesy of the Museum of Food and Drink