New York in the ’60s: Political Upheaval Takes a Turn for the Worst in the Village

“New York in the ’60s” is a memoir series by a longtime New Yorker who moved to the city after college in 1960. From $90/month apartments to working in the real “Mad Men” world, each installment explores the city through the eyes of a spunky, driven female.

In the first two pieces we saw how different and similar house hunting was 50 years ago and visited her first apartment on the Upper East Side. Then, we learned about her career at an advertising magazine and accompanied her to Fire Island in the summer. Our character next decided to make the big move downtown, but it wasn’t quite what she expected. She then took us through how the media world reacted to JFK’s assassination, as well as the rise and fall of the tobacco industry, the changing face of print media, and how women were treated in the workplace. Now, she takes us from the March on Washington to her encounter with a now-famous political tragedy that happened right in the Village–the explosion at the Weather Underground house.

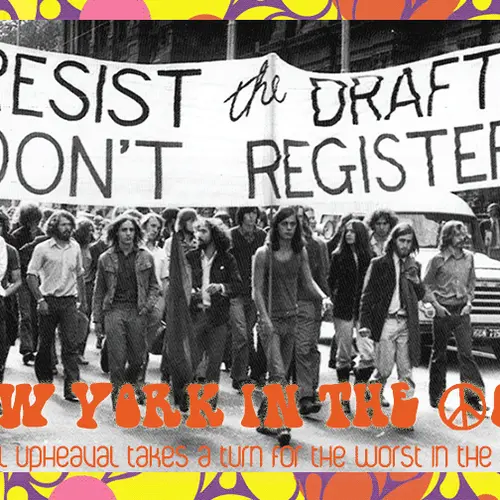

Image via Robert Joyce papers, 1952-1973, Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

The girl didn’t go to the March on Washington in the summer of 1963, but about 200,000 other people did. The Washington Monument Mall was cheek to cheek with people who were marching For Jobs and Freedom, many of them African-American members of churches and civic groups in the South. It was an impressive cross section, according to one of the girl’s friends. Loudspeakers were mounted in the trees, and still her friend could hardly hear and couldn’t see at all that was going on. It was there that Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

A mere ten months later, Freedom Riders were busing to Mississippi to get signatures for voter registration when three of them—Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner from New York and James Earl Chaney from Mississippi—were arrested and detained long enough for a posse to be assembled. Then they were released, followed, murdered and dumped. It was an ugly and brutal incident, and the state refused to prosecute. The Feds finally did, but not until 44 years later.

Andrew Goodman had been a student at Walden School at 88th Street and Central Park West. The school named a building for him, the Goodman Building. Walden has since become Trevor Day School, and the original building was demolished. However, the Goodman building, adjacent to it, still stands and is used by Trevor Day for students from grades six through 12.

Later in the sixties, Columbia University students were protesting, first because of a new gym the university was planning to construct on parkland, then because of racial discrimination and finally, because of the war in Vietnam. It reminded the girl that while she was at college a few years before, Paris students were rioting and her classmates worried that something was wrong with them because they weren’t.

Some issues engaged people all over the world. The Vietnam War was one. Through some English friends, the girl became acquainted with a Scot, a professional Marxist, you could safely say, who had come to the United States to organize Kentucky mine workers. He was quite annoyed with “liberals like Bobby Kennedy” who, he said, “went down there and made everything better so we couldn’t get anywhere with them.” So he came to New York and got a job as a super on West 12th Street while he figured out what to do next.

Every day he read the New York Times for an hour and then spent two hours writing a reaction to what he had read. The girl knew few people who were as internally driven as that. She found him fascinating.

Photo from the day of the Weather Underground explosion

“Come on,” he said to her one day, “We’re going to join the march against the war.” She put on a chic pants suit, tied her hair at the back of her neck with a ribbon and off they went. Arm in arm with the Scot, who was wearing dungarees and a dirty jeans jacket, she found herself at the head of a march of thousands on Fifth Avenue facing a phalanx of photographers, at least some of whom must have been from the FBI or CIA. The chill she felt was not from the autumn air. Years later, she thought the two of them dressed the way they did because the Scot wanted to demonstrate class solidarity against the war. The last she heard of him, he had hooked up with a leader of the Weather Underground.

About two years later, she was taking a break and walking down 6th Avenue when she saw a commotion on West 11th Street near Fifth Avenue and lots of people standing around. She meandered down the street and saw fire engines spraying the south side of the street, a couple of dozen people standing on stoops of houses on the north side watching. There had been an explosion. Dustin Hoffman had come out of a house carrying something that looked like a painting. Everyone was very quiet.

The house being sprayed with water had been the bomb-making headquarters of the Weather Underground, and two of the young people concocting the gruesome brew had themselves been killed by it. One of them had been a leader of student protests two years earlier at Columbia. Two more escaped, had been taken in by neighbors and given clothing, only to disappear for years. The vacationing father of one of the bomb-makers expatriated himself to London, where he continued working in advertising. The house was completely destroyed. An 1845 town house built by Henry Brevoort, was gone along with the lives.

In the 1970s the lot at 18 West 11th Street was bought by the architect Hugh Hardy. The property was in the Greenwich Village Historic District, so the Landmarks Preservation Commission had to approve the design, and controversy followed. Should the design mimic the house that was destroyed? Should it look exactly like the other six or seven houses in that row? Or should it be totally different?

In the end, a compromise was reached: the top two floors would be like the others in the row; the ground and parlor floors rotated 45 degrees to present an explosive angularity to the street. And so it remains today.

+++

To read the rest of the series, CLICK HERE >>

Explore NYC Virtually

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

The account of the Walden School and the Andrew Goodman Building is garbled. The Walden School sold its site on the corner of W. 88 St and Central Park West to a developer who built a multistory residential building. The Trevor Day School took over an adjoining space on W. 88 St and named it’s building after Andrew Goodman, just this year I believe. Walden never named a building after Goodman who had been a student there.