There’s an Historic English Muffin Oven Hiding Underneath This Chelsea Co-op

Although the popular song would have you believe that the muffin man lives on Drury Lane, he actually has digs right here in Chelsea on West 20th Street. 337 West 20th Street, between 8th and 9th Avenues, is a nondescript, four-story brick building that is officially known as “The Muffin House.” Looking at the building from outside, you wouldn’t think there’s anything special to it. But underground, preserved below what is now a modest co-op complex, there’s a massive bakery oven. And not just any old oven, although that discovery is unique in and of itself. This is the oven once operated by a very well-known baker, the one responsible for introducing English muffins to the United States.

Samuel Bath Thomas left his home of England to move to New York in 1874. He gravitated toward Chelsea, which had already developed into a vibrant neighborhood of row houses, churches and businesses. Thomas was interested in starting a commercial bakery, so he chose a location near the Hudson River, which was affordable, but also close enough to the businesses lining Broadway. According to Daytonian in Manhattan, he opened his first bakery at 163 9th Avenue in 1880.

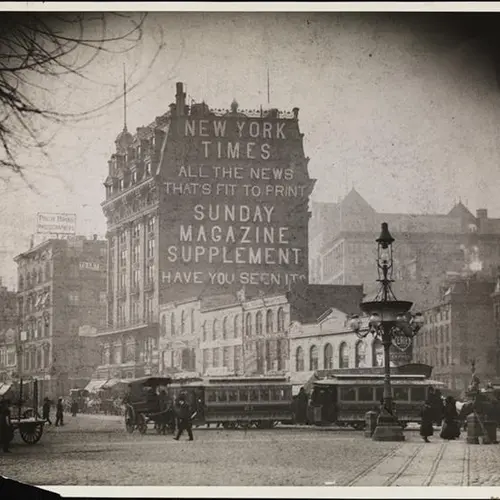

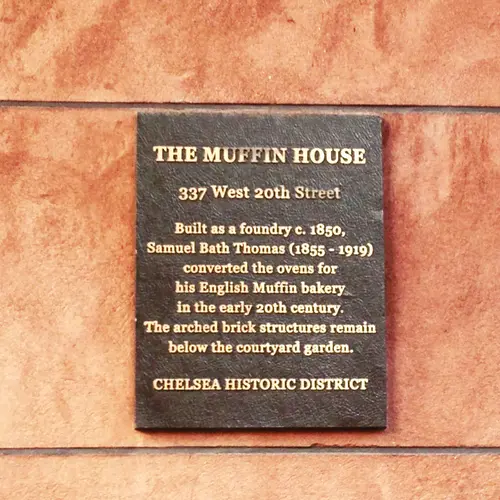

Chelsea area in 1897, courtesy the Museum of City of New York

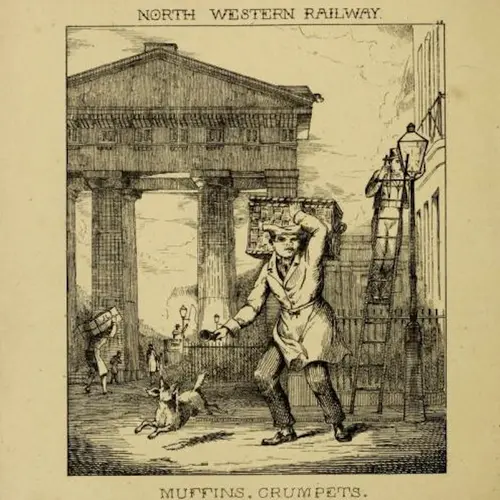

Thomas knew he had a valuable recipe on his hands that had yet to be introduced to New Yorkers. It was that of an English muffin—a historic English recipe for muffins typically sold by street hawkers door-to-door as a snack bread in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (this was before most houses had private ovens). This practice gave rise to the traditional song, “Do You Know the Muffin Man?”

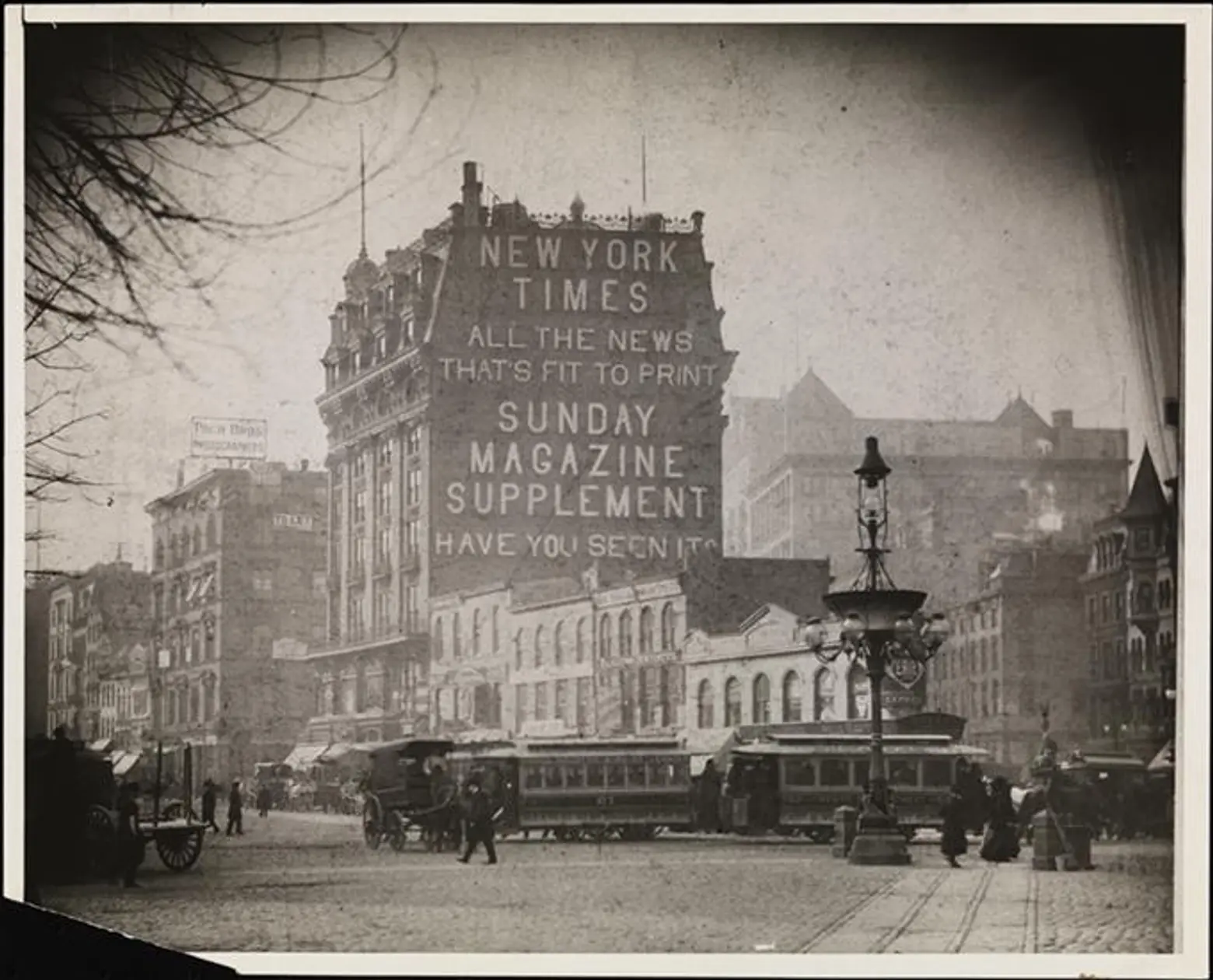

A muffin man ringing his bell in England circa 1850s, courtesy of London cries & public edifices

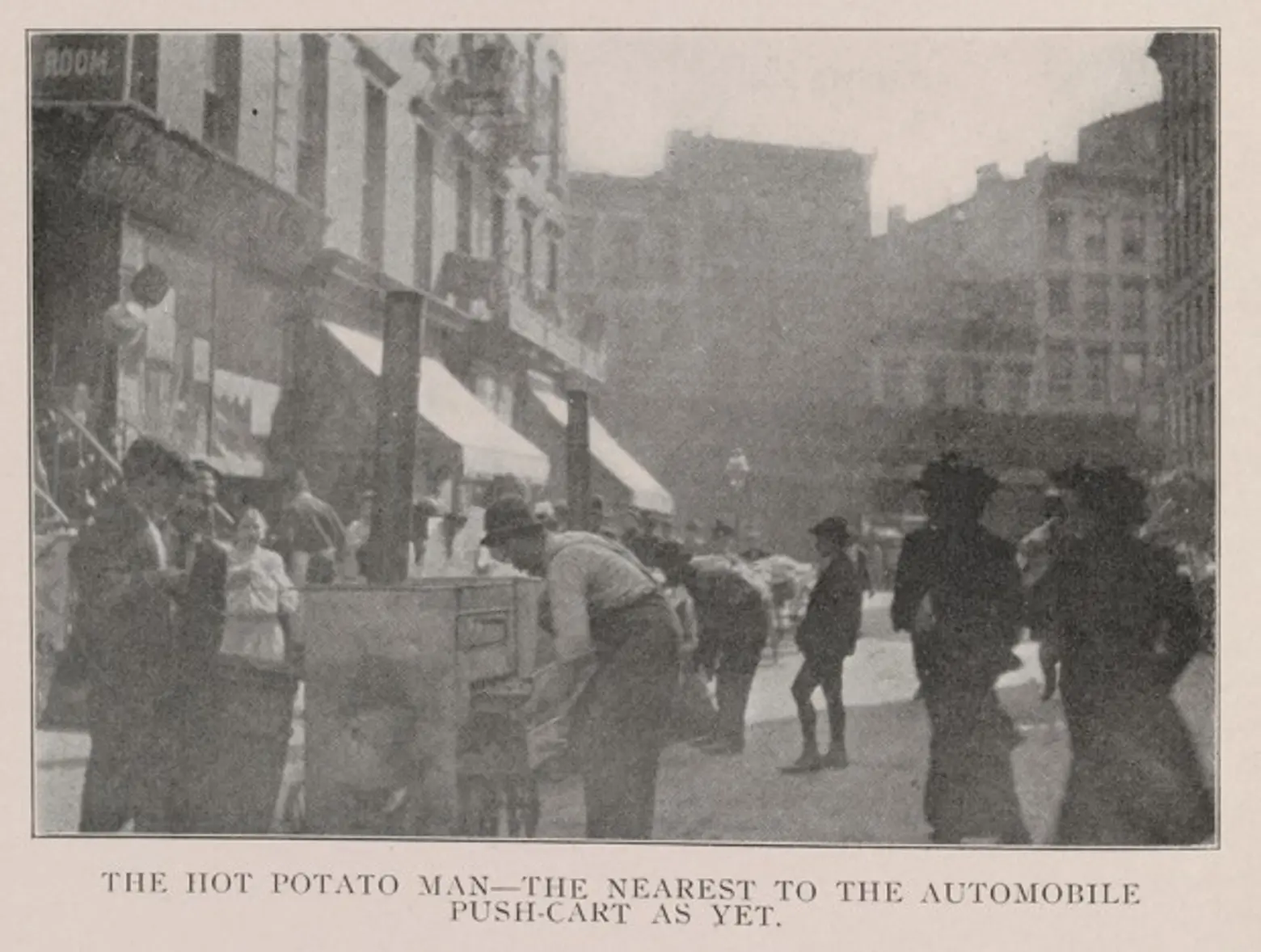

At Thomas’ first bakery, he sold only to commercial establishments, advertising direct delivery “to hotels and restaurants by pushcart.” At the time, pushcarts were the common way to transport and sell food. Most carts sold fruits and vegetables, while others sold prepared foods like potato pancakes, oysters on the half-shell, or pickles. Here are more details from the Bard Graduate Center: “Carts tended to specialize in a particular food type and were often stationed in the same place every week. They were not the type of prepared food vendors or food trucks that are in fashion today. Instead, they offered a basic and necessary service: providing ingredients for meals to their customers at relatively cheap prices.”

The Hot Potato Man pushcart, courtesy of Bowery Boogie

The Hot Potato Man pushcart, courtesy of Bowery Boogie

Demand for Thomas’ pushcart was spreading all the way to the Bronx and Queens. It prompted him to open a second bakery, this one at 337 West 20th Street, sometime in the early 1900s. At the time, this block of West 20th was mostly residential and didn’t seem like the obvious place for a bakery. But the brick-and-brownstone building, which dates back to the 1850s, had previously housed a foundry in its lower floors. It’s believed that the foundry already had ovens built into the basement, making this a logical location for Thomas to easily open his own bakery.

Thomas renovated the building, only slightly altering the facade. In the basement, his massive brick oven stretched back underneath the building’s garden. He made muffins in this location until his death in 1919. His family initially took over the business, but after they decided to sell it the West 20th Street bakery was abandoned. Still, more than a century after Thomas came to New York, the infamous muffin still carries his name.

The garden at 337 West 20th Street, Image courtesy of Halstead

The garden at 337 West 20th Street, Image courtesy of Halstead

Somewhere along the line, the building was converted for residential use and the brick oven under the garden was walled off and forgotten. According to Daytonian in Manhattan, there were two apartments built out per floor by 1952.

In 2006, the New York Times published a story about the discovery made by two co-op residents, Mike Kinnane and Kerry McInerney. They had peeked behind their basement wall and spotted a room-size brick oven, 15 feet from side to side and another 20 feet from front to back. After cutting a section from the basement bedroom wall and shining a flashlight, they could see, “a broad arch of bricks, charred black in some places, [serving] as the oven’s roof.” Those brick arches spanned back to take up most of the space beneath the apartment building’s courtyard.

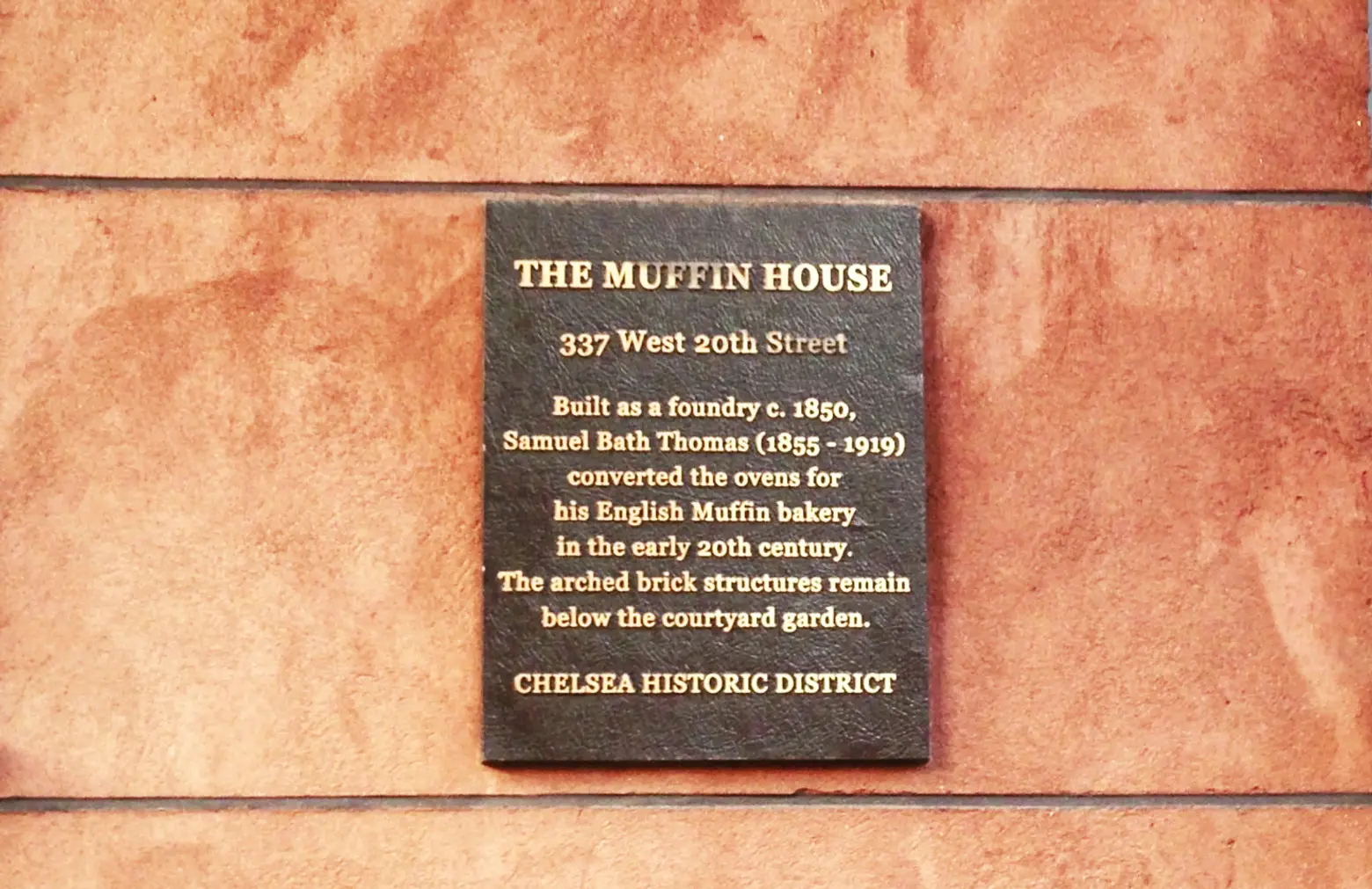

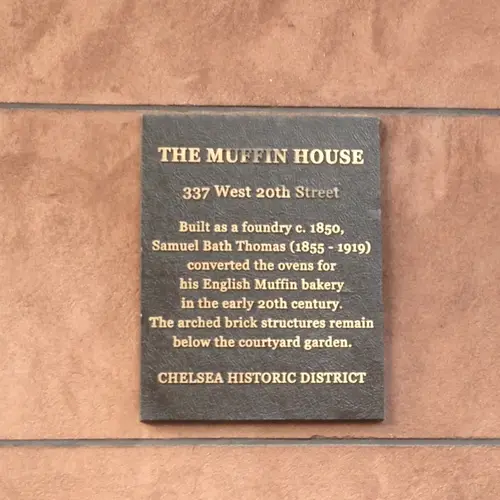

Since the oven was built on site, it cannot be easily removed—“You try to move it, and all you’re going to end up with is bricks,” an engineer who helps oversee current-day Thomas’ plants told the Times. And so it remains in the basement of this Chelsea co-op building, hidden from sight. There’s a plaque decorating the facade that singles this out as “The Muffin House,” and the building was celebrated this year during Thomas’ 135th anniversary. Otherwise, it’s just an average Chelsea co-op with an incredible piece of culinary history underneath it.

RELATED: