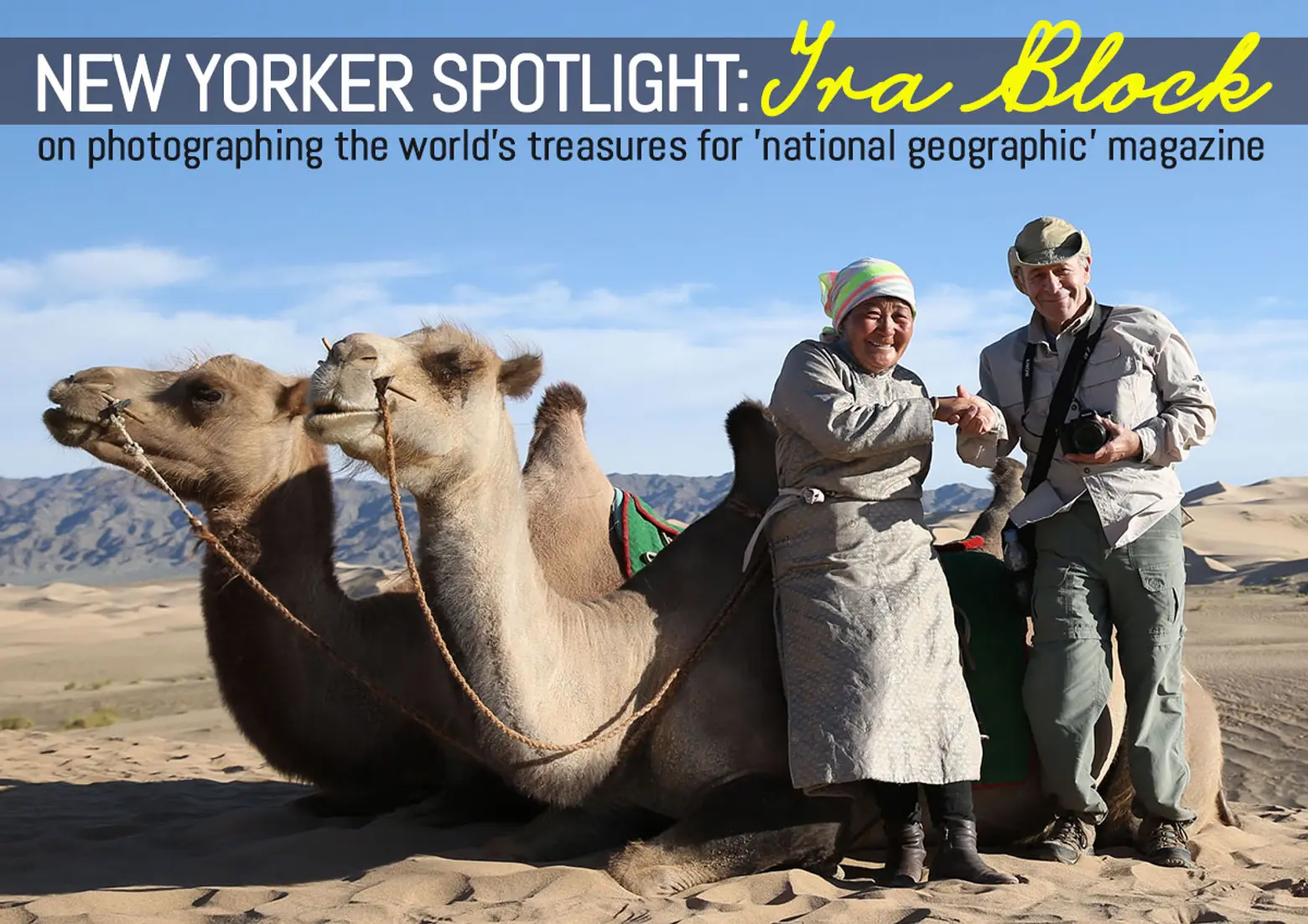

New Yorker Spotlight: Ira Block Photographs World Treasures for National Geographic

Ira with a camel and a local in the desert of Morocco, © Connor Dugan

When Ira Block leaves his New York City apartment for work, he might find himself on the way to Bhutan or Mongolia. As a photojournalist who has covered more than 30 stories for National Geographic magazine and National Geographic Traveler, Ira travels the world photographing some of its greatest marvels. He’s captured everything from far-off landscapes to people and animals to discoveries made at archaeology sites.

In between trips to Asia, Ira spends time photographing baseball in Cuba. The project has afforded him the opportunity to catch the country on the cusp of change. His first images showing Cuba’s passion for the sport, mixed in with its beautiful but complex landscape, are on display at the Sports Center at Chelsea Piers.

We recently spoke with Ira about traveling the globe for work and how his career and passion have shaped his relationship with New York.

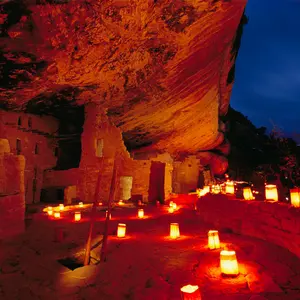

Mesa Verde, Colorado

Growing up, were you interested in photography?

I started around my junior year of high school. One of my teachers had a photo club, and I liked it, so I built a darkroom in my house. It was amazing just to watch prints appear, and of course I thought I was good until you see something better.

It was a hobby in high school, but when I went to college, I started working on the student newspaper, not thinking I would be a photographer. I did take some Art History classes in college, as well as classes in the history of motion picture. I was taking things that were helping me become more visually oriented. And then I got hired by a local newspaper in Madison, Wisconsin to help them photograph things during a lot of Vietnam War protests. So I learned almost as an apprenticeship.

Why did you decide to work in photojournalism?

I thought that photojournalism was a place where I could travel, see places, and also tell a story with my photos. I was from New York originally, but after school I lived in Chicago for a bit of time. I came back to New York and freelanced for some magazines (back when magazines were bountiful), and I had a friend who was at National Geographic. He introduced me to some people there, and I thought wow, National Geographic, that’s a place to work. I got in, and I’ve been freelancing with them for over 30 years now.

Little Diomede in the Bering Sea, Alaska

What was your first story for National Geographic magazine?

The first story in the magazine was one that some other photographers had started, and they asked me to come in and try it out. It was on the continental shelf around the United States. A lot of the pictures I had to do were on oil rigs and fishing vessels, which was something I’d never done. But then to make the story work, I looked for lesser known things that happen on the continental shelf.

After that I did something for their book division called “Back Roads of America,” where I drove around the United States in a VW camper van and photographed small towns. And after that, I was asked to go to the North Pole with a Japanese explorer who was going by dog sled. That was quite an experience; it changed my life. I’m a city kid and now suddenly I’m going to the North Pole. It taught me survival. The Japanese team didn’t speak any English, but we lived together in the ice desert, so it taught me about interrelationships.

How do you prepare for your National Geographic shoots?

There are a lot of places I’m very familiar with in the world so it’s easy for me to go back there. But if it’s a new place I’ve not been, I have to do quite a bit of research and speak to friends of mine who have been there; find out who they use as a local fixer. I do a lot of stories that are science- or history-based, so it takes even more research. I look at books and I go online. It’s amazing how I did things without the internet in the late ’70s and ’80s when I first started, but somehow I was able to do it.

Camels in the desert is Morocco

What do you pack?

I pack carefully. I try to remember everything because I bring a lot of lighting equipment, and with all the digital stuff there are so many cords and little connections I need that I don’t want to forget anything, especially if I’m going to a remote place where there’s no stores. The least important thing for me is my clothing. That’s easy to pack. Usually I have the right clothing for the weather. In certain places I do pick up stuff that’s local for the weather because it works to that climate. So if I’m in an arctic region, usually they have good gloves and boots there. If I’m in a desert region like Morocco, I’ll get one of the big turbans.

Do you have to carry a lot of supplies with you on site?

A lot of the artifacts I can’t touch, or I’ll have to let [the archaeologists] touch them. I’ll create a little studio on location, which is why I have to carry so much stuff. Not only do I have to carry my lights, I have to carry backgrounds and all kinds of grip equipment to hang things.

Tigers Nest, a monastery on the side of a mountain in Bhutan

Monk taking a selfie in Luang Prabang, Laos

What are some of the diverse locations you travel to for work?

In recent years, I’ve been doing a lot of work in Asia, Southeast Asia, and South America. I like going there because it’s still so much different, whereas Europe now is very similar to the U.S. I just came back from Mongolia, which is still very authentic. Thirty to forty percent of the county is still nomadic. I’ve been to Bhutan a lot. I’ve been working on a project on Buddhism so being in these countries is good. And of course, I’ve been to Cuba a lot.

What are some of the stories you covered in Southeast Asia and South America?

I did a story a few years ago in Japan on the age of the samurai because that time period was interesting to me. In South America I’ve done a lot of stories on archaeological sites, especially in Peru, where I’ve been many times. They have very rich archaeological history, and more importantly, the archaeology is preserved. A lot of times, due to weather and climate, the archaeology is not preserved. If it is preserved, there are great artifacts and mummies to photograph.

Stars and a yurt in Mongolia

Is there one location that really captured your heart? Or do you have spot for all of them?

Every place is special to me. Usually the last place I’ve been is the most special. I really like Mongolia because it’s still is so real. And I really like Cuba because it’s just interesting going to a communist country. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, I was in the then Soviet Union a lot; I call that cold weather communism as opposed to warm weather communism. When I got to Cuba for my first trip in 1997, I was in shock that this was communism. It’s totally different.

An elevated view of a crowd in Marrakesh, Morocco

Do any of your stories take you to high shooting locales, like from helicopters or hilltops?

I’ve done a lot of work out of helicopters. They provide an incredible view that most people can’t see. I’ve done pictures out of ultralights when helicopters weren’t available. Now, of course, people are using drones. That’s become controversial, but it’s easy, less expensive, and less complicated than a helicopter. If the weather isn’t right for photos, you’ve got this expensive helicopter sitting there waiting, whereas with something small like a drone, you suddenly say, “Wow, the weather is clear. Let’s put it up.” I also climb a lot of mountains and hills. That kind of view is great for people because they get to see a place in a certain context that they haven’t seen before.

When photographing for a story, are you ever surprised by what you end up capturing?

You have to be careful about your expectations when you go out and start a story. I try to go with no expectations and just see what’s there. Sometimes an archaeologist or scientist will say to me, “There’s a great city there. There’s all this.” And I get there, and it’s there, but it’s visually not there, and then I’m disappointed. There are times I go out and it takes a lot of work and thought on my part to find really dynamic photographs. Other times I get to a place and I think, “Wow, look at this, it’s great.” It’s easy to take the pictures. It’s just depends on where you are and what’s going on.

Tibet

Kathmandu, Nepal

While working, do you have the opportunity to speak with locals and sightsee?

I interact with locals when I’m working more so than I would as a tourist. I really have to get into their culture, talk to them, and become friends with them. As far as sightseeing goes, with my job I usually get to see some pretty interesting things.

Does the amount you travel shape how you interact with New York?

I’m traveling about six months of the year. Early on, I used to travel eight or nine months. It’s great coming back to New York. When I’ve been gone for a while, I come back and there’s so much I can do here. Although if I’ve been to a very quiet and tranquil place, I get back and New York overpowers me with stimulus. There’s just so much noise, so many smells, and so much going on that it takes me a while.

Is there anything you like to do in the city as soon as you get back?

I do love pizza and New York has the best pizza. So if I’ve been to some remote place, as soon as I get back I’ll go get a slice of pizza. Although in Bhutan in Thimphu, which is the capital, I found a really great pizza, and I know pizza.

While home, do you spend time photographing New York?

In the past I haven’t, but now I’m making more of an effort to do it. Also because I’m so big on Instagram it forces me. It’s made me open my eyes more to look for New York scenes to put on my Instagram account.

Do you think Instagram is helpful as a photographer?

To me, it’s become a professional way of getting my images out there to an audience. I think Instagram is a new way of communicating. On my account, I’ve got 180,000 followers. When Nat Geo, which has 25 million followers, posted one of my photos it got 580,000 likes. That’s a lot of communication. Most magazines don’t have that circulation.

Before, when I was just putting stuff in National Geographic, which had millions of subscribers, I felt good about my images being seen by many people. But now with Instagram and Facebook, I get comments from people and I interact with them. It’s a new ways of getting personal satisfaction and having people appreciate my pictures and ask questions not just about the photos, but the cultures I’m exposing them to.

You are currently photographing baseball in Cuba. What inspired this project?

I’ve been to Cuba many times on projects for National Geographic. I’m a baseball fan in general and when I was there about two and a half years ago, I noticed that baseball was such a big part of their culture. I didn’t know how long it would last, so I started photographing baseball, not so much as an action sport, but as a cultural entity. And then just recently, everything started opening up between the U.S. and Cuba, which made me really glad I was documenting this.

Baseball in Cuba is a pure sport. Baseball in the U.S. is like most other professional sports–television contracts and money. To me, baseball in Cuba is probably like baseball was in the U.S. back in maybe the ’30s or ’40s before there were big TV contracts. The average professional baseball player in Cuba gets $100-200 dollars a month, and so people play baseball for the love of it. But I think ten years from now that will change in Cuba, so I’m lucky that I got in when I did to document this historic moment.

Several of the photos from this project are on display at the Sports Center at Chelsea Piers. Why did you feel this was a good place to share these images?

In the last number of years, Chelsea Piers has exhibited art that relates to sport. There was an exhibition coming up, and my friend Roland Betts who owns Chelsea Piers asked me about putting up some photos. Originally I thought about putting up photos of New York, but that doesn’t really relate to sport. New Yorkers see New York in pictures all the time. Roland knew I was doing this baseball project in Cuba and asked me to put it up. Though I wasn’t finished with it, I thought it would be a good opportunity to see my pictures hanging and not looking at them on a computer because the computer world has locked me in so much.

You teach workshops all over the globe. What is one thing you always tell your students?

When I teach a workshop, I don’t teach a technical workshop. I teach a workshop on how to visually see pictures. I try to teach the difference between what your brain sees and what your eyes see and what the camera sees. A lot of that has to do with composition. I’m very finicky on composition because that’s something that you can control without having too much technical knowledge. I teach a lot about foreground, middle ground, and background and how that builds your image, so basically composition and light. To me, light is an integral part of the composition.

What does capturing moments in time and sharing them with the world mean to you?

I’ve been really lucky. My life has been exposed to so many different cultures and people, it’s just opened my mind to the world. If you live in a place like New York and you don’t get out too much, you’re not aware of what the rest of the world is really like.

+++

[This interview has been edited]

RELATED:

- New Yorker Spotlight: Brian and Andy Marcus Carry On a Three-Generation Photography Tradition

- New Yorker Spotlight: Meet the Human Behind The Dogist, Elias Weiss Friedman

- Photographer Bob Estremera Shows Us That Greenwich Village Is Still Full of Character

All photos © Ira Block