Before NYC’s Slave Market, Freedmen from Africa Were Allowed to Own Farmland

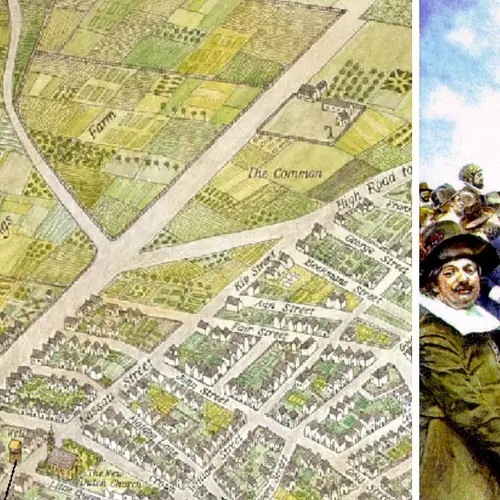

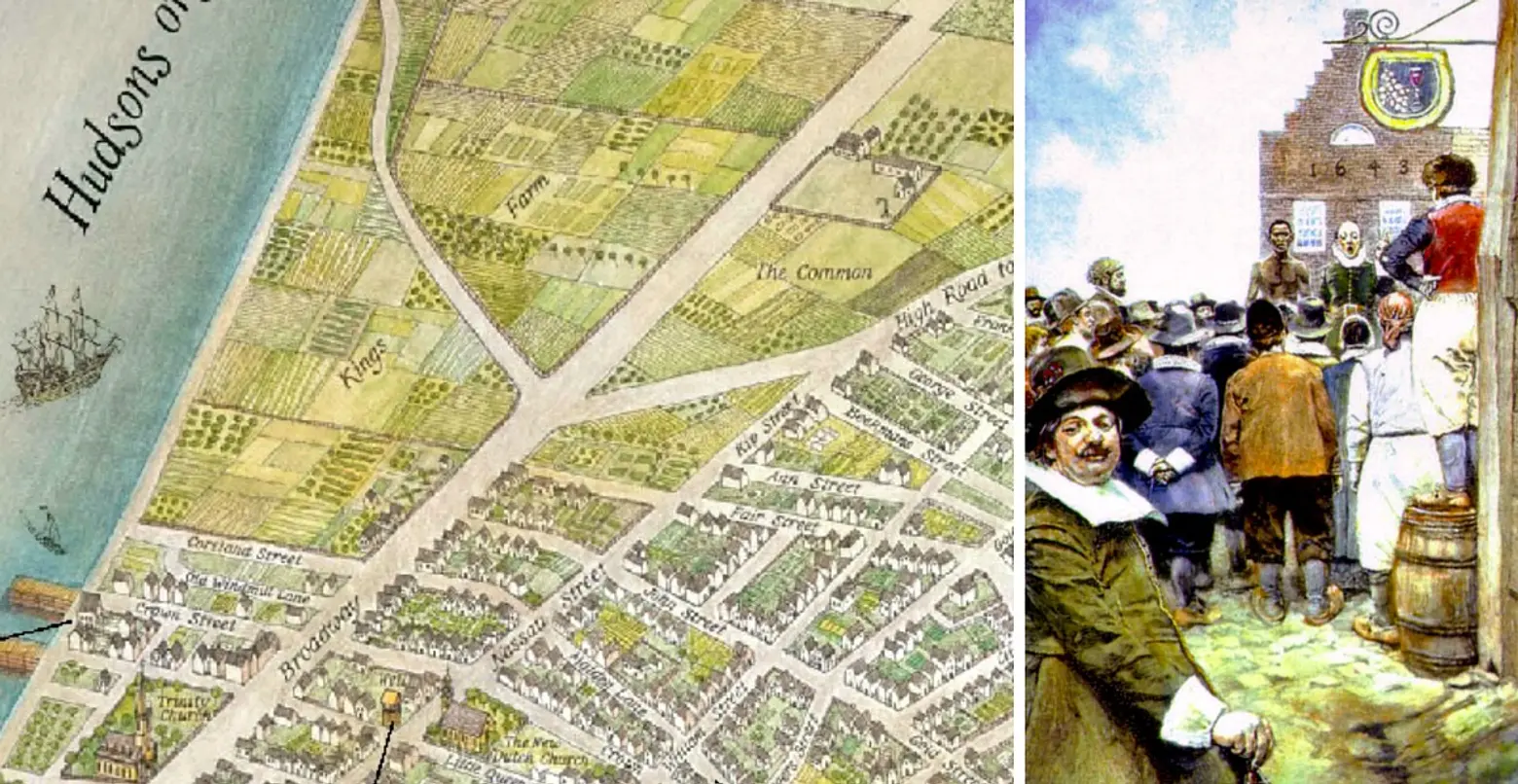

Map of freedmen’s farmland via Slavery in New York (L); Harper’s Magazine illustration of the New York City slave market in 1643 (R)

A stranger on horseback in 1650 riding up a road in Manhattan might have noticed black men working farmland near the Hudson River. It was not an unusual sight, and if he remarked on it at all to himself, he would have thought they were simply slaves working their masters’ land. But no–these were freedmen working land they personally owned and had owned for six years. It was land in what is now the Far West Village and it had been granted to eleven enslaved men along with their freedom in 1644.

In 1626, the year Manhattan was formally settled by the Dutch, these eleven African men had been rounded up in Angola and Congo and shipped to the New World to work as slaves clearing land and building fortifications. We know they were from there because the manifests of Dutch ships list them with names such as Emmanuel Angola and Simon Congo. Another of the eleven was named Willem Anthonys Portugies, suggesting that he may have been bought and sold in Portugal before reaching his final destination in New Amsterdam.

Under the Dutch, slaves built a fort, a mill, and new stone houses. They broadened an Indian trail and turned it into Broadway; and they worked the farms of the Dutch owners, planting, harvesting and managing them when the owners were away. The rules governing slavery allowed men to own land and to work for themselves in their spare time. Little by little, by dint of quick wits and good luck, some Africans had been able to acquire small lots of land. Some were men whose owners had freed them, believing they had done their time. Some were men who had been able to buy their freedom and then some land. An area of what is now Greenwich Village was occupied by some of these small “free Negro lots,” parcels east of Hudson Street near what is now Christopher Street—the ones espied by the stranger on horseback.

It was, however, an unsettled time of nearly constant warfare between the Indians and the Dutch, and a time of fairly fluid contracts that might or might not be honored. So even though the slaves owned some land and worked it, they fought alongside the Dutch when required to do so. They were not free enough to refuse.

The African Burial Ground

In 1644, the eleven men petitioned the Dutch West India Company for their freedom and that of their families, and they were granted it along with some land. Their wives were also granted freedom, but not their children, although eventually they were able to buy their children’s freedom. One of these eleven men, Emmanuel Angola, married a woman brought from Africa, Maria, and became a landowner and father. The two are ancestors of Christopher Moore, historian, writer and a former Landmarks Preservation Commission commissioner well known for his role in securing preservation of the African Burial Ground in Lower Manhattan. In his 1998 book, “Santa and Pete,” he says Big Man, as his ancestor was known, “loved to whittle” wood and that family history had been passed down in the twelve generations since Big Man’s time by word of mouth and notations in a family bible.

By the time of the 1644 grant, constant warfare had depleted Dutch resources, and as dependents the slaves had become a costly burden. Moreover, since the Africans had fought with the Dutch in recent wars, it behooved the Dutch to keep them allied in case they needed to be called on again. So they were given grants of farmland and offered “half freedom,” the liberty to live and work for their own benefit unless and until the Dutch needed them again. Their children, however, would be the company’s property.

Map of New Amsterdam in 1664, via NYPL

In addition to plots of African-American-owned land near the river were others at the southwest corner of what is now Washington Square Park, the west side of Bowery, and the east and west sides of Fourth Avenue around present-day Astor Place; still another was located at the intersection of what is now 8th Street and Fourth Avenue. The Dutch settlement was to the south, at the tip of Manhattan, so these were remote properties at the time.

The placement of these properties was critical in Dutch thinking: The Dutch were wary of invasion from the north, either by Indians or the English, and the African farms presented a bulwark against that. The former slaves would defend their own property, so the thinking went, and thereby forestall or squelch a military attempt on the main settlement. Eventually the black farms dotted a belt across Manhattan, extending in plots from Canal Street to 34th Street.

Drawing of the Wall Street slave market

For all that, the English eventually did invade and conquered the Dutch in 1664, renaming their acquisition New York. This was not good for the Africans, for the English rescinded many of their rights, including the right to own land, and they lost their property in 1712. Not only that, but the Duke of York (later James II) awarded port privileges in New York to slave ships because he was a principal investor in slave trafficking; the city became a major slave market in the beginning of the 18th century. The market was located at the present-day corner of Wall and Pearl Streets, and by the year 1700, 750 of the city’s 5,000 people were slaves. This number would increase by several thousand in the coming years. Hundreds of these people were free African Americans who were captured and sold into slavery. It puts one in mind of Solomon Northup, born free in New York in 1803 and sold into slavery as an adult. He wrote about his experiences in a book entitled “Twelve Years a Slave,”which was made into a movie of the same name in 2013. As we reported in a recent article, on June 19th the city added a historical marker to the site where the slave market once operated.

RELATED: