Crimes Against Architecture: Treasured NYC Landmarks Purposely Destroyed or Damaged

At Monday’s MCNY symposium “Redefining Preservation for the 21st Century,” starchitect Robert A.M. Stern lamented about 2 Columbus Circle and its renovation that rendered it completely unrecognizable. What Stern saw as a modernist architectural wonder, notable for its esthetics, cultural importance (it was built to challenge MoMA and the prevailing architectural style at the time), and history (the building originally served as a museum for the art collection of Huntington Hartford), others saw as a hulking grey slab. Despite the efforts of Stern and others to have the building landmarked, it was ultimately altered completely.

This story is not unique; there are plenty of worthy historic buildings in New York City that have been heavily changed, let to fall into disrepair, or altogether demolished. And in many of these cases, the general public realized their significance only after they were destroyed. In honor of the 50th anniversary of the NYC landmarks law, we’ve rounded up some of the most cringe-worthy crimes committed against architecture.

The Original Penn Station

Here’s what started it all. Built for the Pennsylvania Railroad, the original Penn Station was a Beaux-Arts masterpiece completed by McKim, Mead & White in 1910, meant to welcome travelers to New York in a grand public space. The façade of the station boasted 84 pink granite, Corinthian columns. Inside, the 15-story waiting room emulated a Roman bathhouse with a steel and glass roof through which natural light filtered down into the massive space.

By the 1950’s, with the rise of the automobile, train ridership had declined, and the Pennsylvania Railroad sold the air rights above the station to create a new Madison Square Garden and office towers, as well as a new, nondescript station below. When the demolition plans were announced, preservationist Jane Jacobs and architects Robert Venturi and Philip Johnson were among those who picketed outside the station. Their efforts may not have saved the original Pennsylvania Station, but they are credited with the official creation of the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965, just two years after the station was razed.

Former Brokaw Mansion

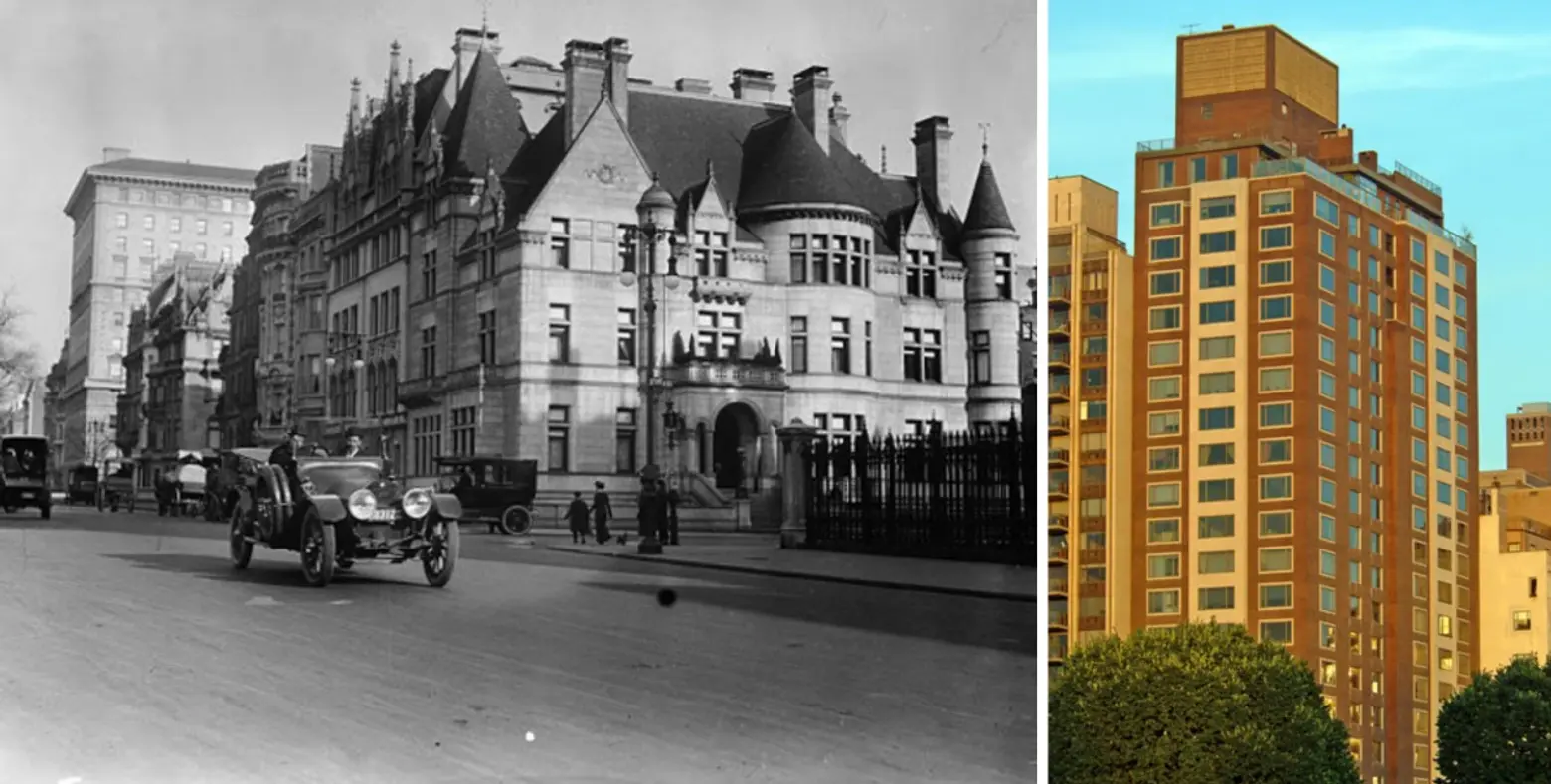

Another early contributor to the modern-day preservation movement, the Brokaw Mansion was built in 1890 for Isaac Vail Brokaw, a prominent multimillionaire clothing manufacturer. Architects Rose and Stone designed the lavish home to resemble the 16th century Château de Chenonçeau in France’s Loire Valley. Located at 1 East 79th Street at the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue, the limestone mansion had an elaborate façade full of turrets, balconies, gables, and finials. Inside, the Italian and French décor included a plethora of stained glass, marble and mosaics.

Historic photo cc

Historic photo cc

In 1946, the Institute of Radio Engineers purchased the mansion as an office space after it had sat vacant for eight years. The Landmarks Preservation Commission was formed in 1964, but had no legal power. Later that year, demolition permits were filed for the Brokaw Mansion. Preservationists and art critics urged Mayor Wagner to give the LPC the right to stop the demo, but on a Saturday, with city offices closed, the building was taken down. A modern, high-rise apartment tower known as 980 Fifth Avenue stands in its place.

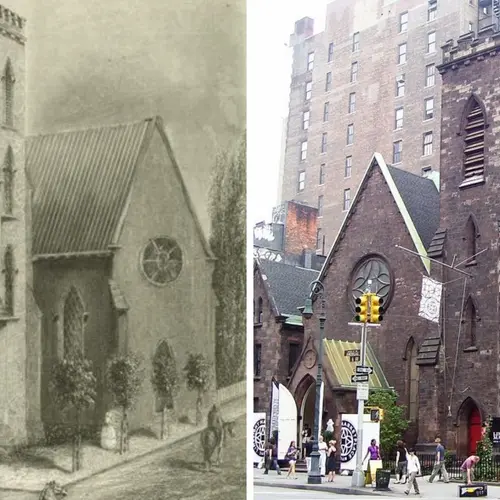

Episcopal Church of the Holy Communion

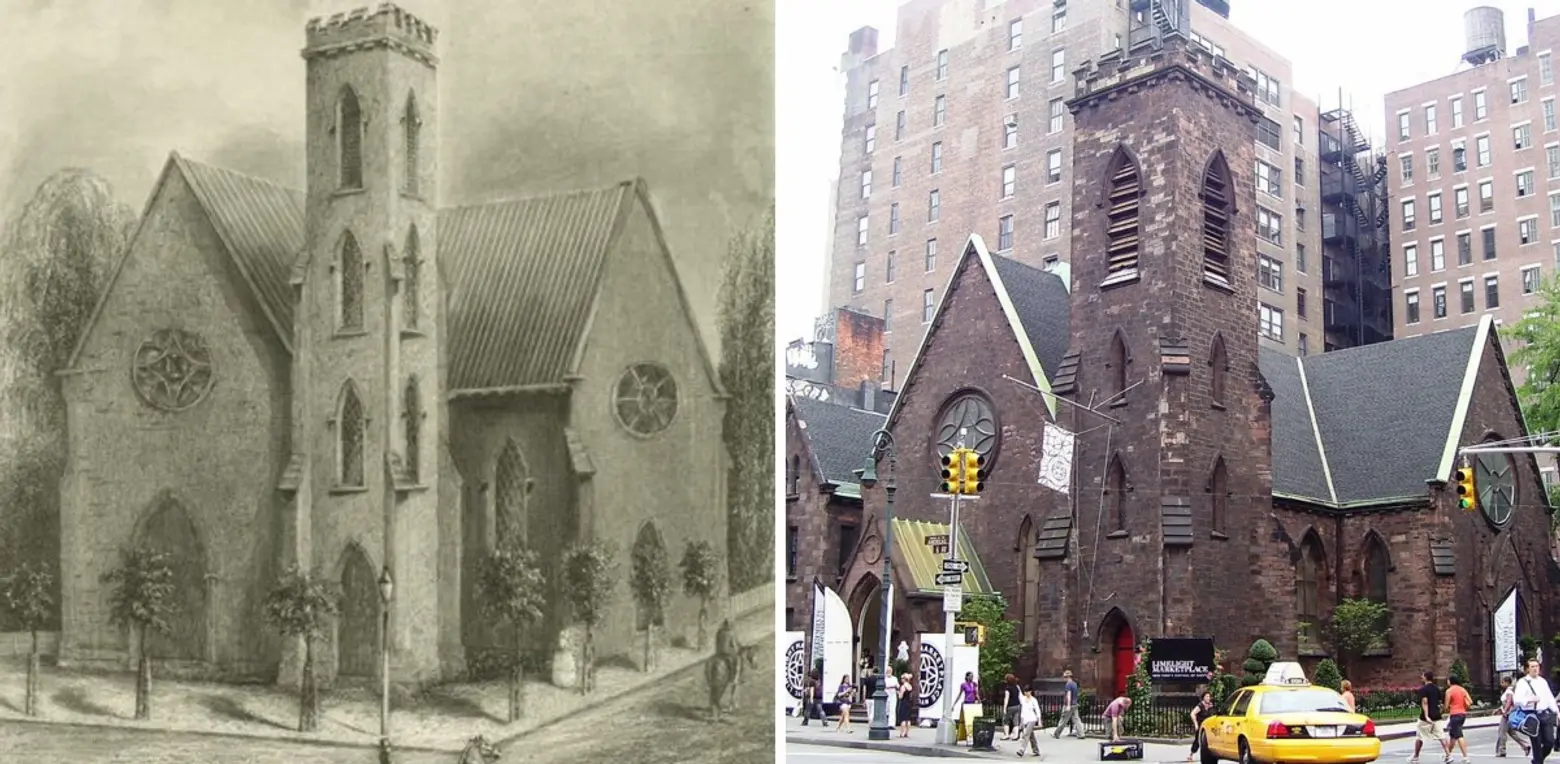

This Chelsea building went from house of worship to raving nightclub to high-end shopping mecca–one could argue that it follows the trajectory of the city in which it was built. The famed architect Richard Upjohn, also responsible for Trinity Church, designed the Episcopal Church of the Holy Communion in the Gothic Revival style in 1845. It was a modest structure that served its working-class community.

Historic image via NYPL

Historic image via NYPL

In the early 1970s, the parish merged with two others, and the church was deconsecrated. Ten years later, nightclub impresario Peter Gatien turned the structure into the Limelight, an iconic club of the 1980s that was famous for its all-night raves. Andy Warhol hosted the opening-night party, and Madonna, Cindy Crawford, and Eddie Murphy were among the other partiers. The club closed in the 1990s after a drug bust, and is now the Limelight Shops, an upscale shopping emporium that was created through a $15 million gut renovation. Though much of the interior shell has been retained (the exterior is a city landmark, so it is protected), its former humble beginnings as an accessible place to anchor the community have not.

The Coignet Building

Frenchman Francois Coignet is credited with bringing concrete construction to the United States. He became president of the New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company, which moved its headquarters to a location on the Gowanus Canal in 1872. Their office and showroom was an advertisement for concrete construction and the ornamental features that could be cast in the material. The landmarked building was once part of a five-acre complex, but now stands alone.

Historic image © David Gallagher

Historic image © David Gallagher

In 2005, Whole Foods bought the property and built a new store next to the Coignet Building. As part of its construction deal with the city, the supermarket agreed to fix up the historic structure, but instead the building has been in worse shape than ever, with actual pieces of the façade falling off. In 2013, Whole Foods put the building on the market for $3 million, and later that year they were slapped with a $3,000 fine from the Landmarks Preservation Commission for “failure to maintain.” They have since begun repair work, but no word yet on who the new owner will be.

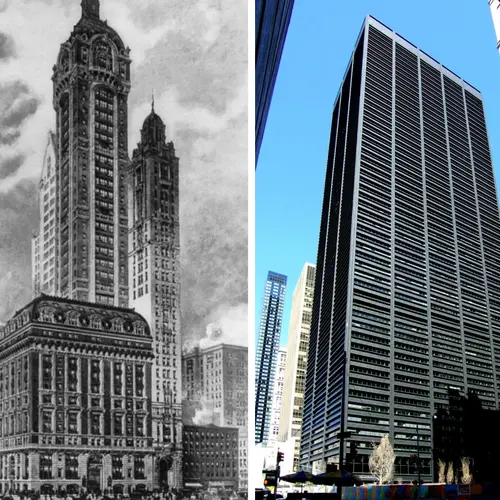

The Singer Building

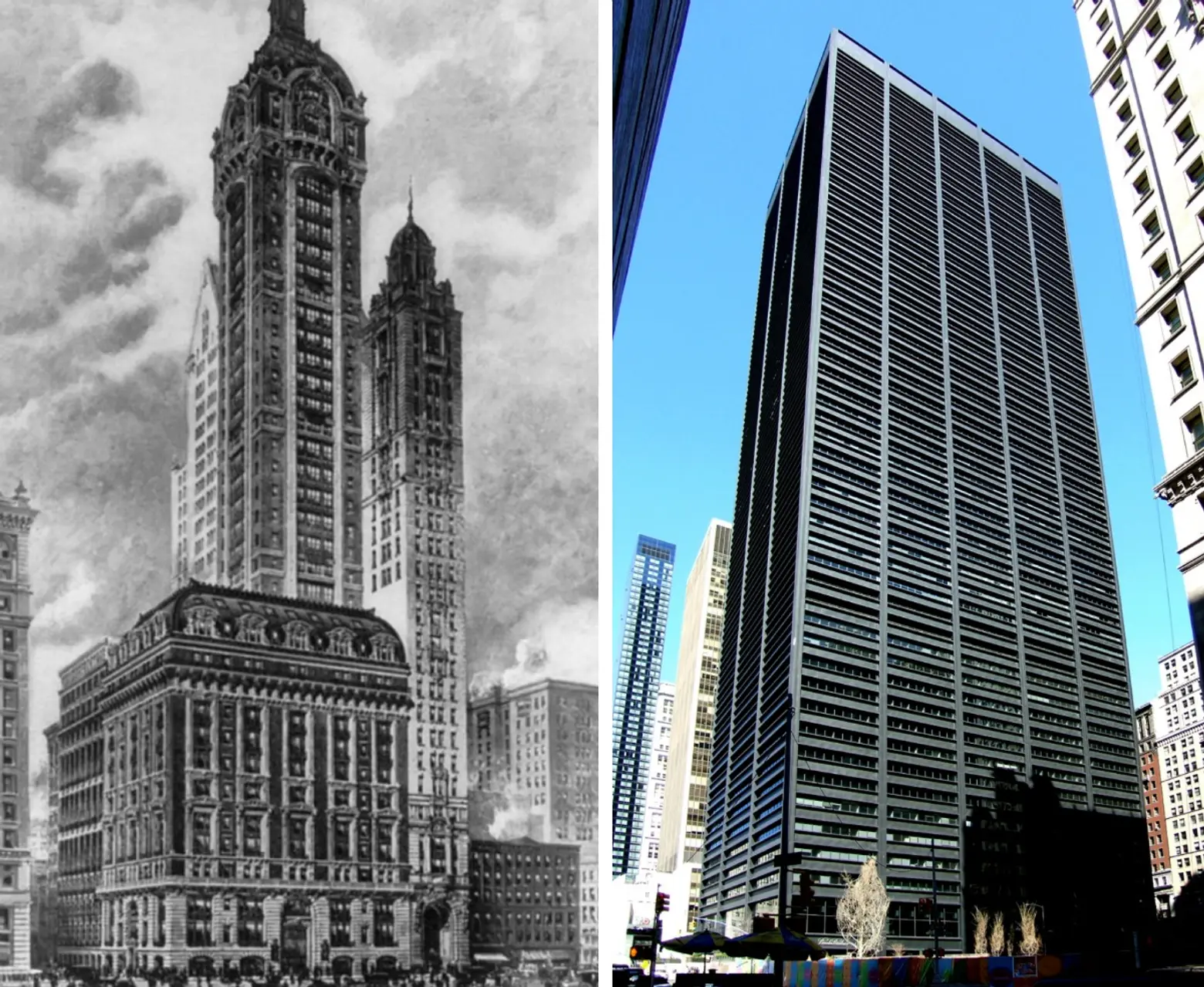

The Singer Building was constructed in 1908 by Ernest Flagg in the Beaux-Arts style for the Singer Manufacturing Company. Standing at 41 stories, it was the tallest office building in the world until 1909 when it was surpassed by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Flagg had previously designed a full-block, 12-story headquarters for the company in 1896, and he used this as the new building’s base, with the added tower rising at a much narrower setback (Flagg was an early proponent of thoughtful skyscraper design).

Photo of One Liberty Plaza © Marshall Gerometta CTBUH

Photo of One Liberty Plaza © Marshall Gerometta CTBUH

In 1968, the Singer Building set another record when it became the tallest building ever demolished, a title it held until September 11, 2001. Singer had sold the building in 1961 to real estate developer William Zeckendorf who unsuccessfully lobbied for the full block to become the new home of the New York Stock Exchange. When United States Steel bought the site in 1964, they made plans to demolish the Singer Building to build what would become One Liberty Plaza. Though the LPC was formed by the time demolition commenced in 1967, the structure hadn’t received landmarks status, despite its iconic standing. It’s speculated that the tower’s small floor plans were to blame for the lapse in designation, as finding tenants would have been challenging.

St. Ann’s Church

St. Ann’s was a Roman Catholic parish that spent its early days on Lafayette Street, but later moved to an existing church on East 12th Street between Third and Fourth Avenues in 1870. The religious structure was built in 1847 as the 12th Street Baptist Church, but housed the Emanu-El synagogue from 1854-67. When St. Ann’s moved in, Napoleon LeBrun designed a new French gothic sanctuary that extended back to Eleventh Street. At the time, it was one of the wealthiest congregations in the city, but in 2003 the church permanently closed.

Photos © GVSHP

Photos © GVSHP

When NYU announced plans to erect a massive, 26-story dorm on the site in 2005, preservationists and neighbors were outraged, claiming the development was out of scale with the surrounding neighborhood. In an attempt to compromise, the university retained only the façade of the historic church, and built the dorm as an unconnected structure directly behind it. This strange concession did not do NYU any favors, though, as the resulting dorm made no effort to contextualize itself with the lonely church remnant.

5Pointz

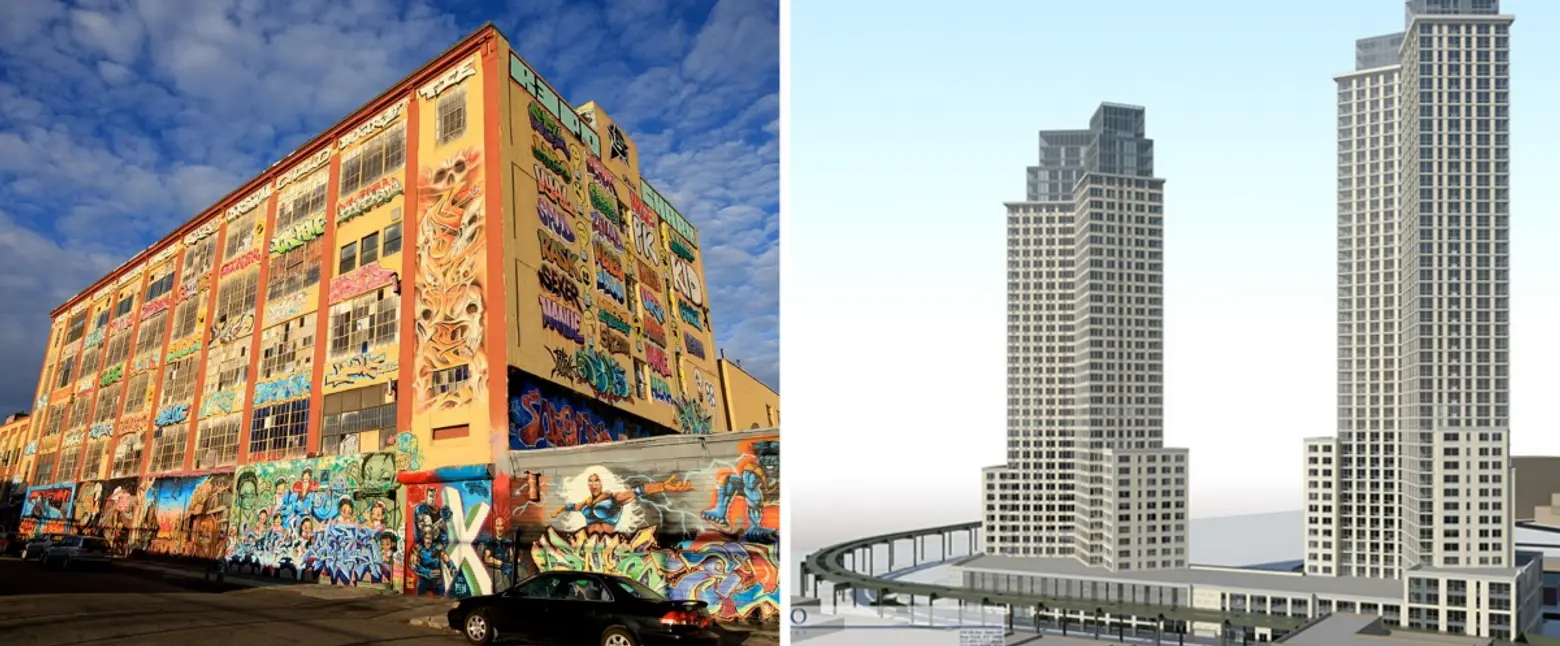

A wound still fresh in our hearts, the loss of 5Pointz was more than just a building demolition; it was the end of an era for a cultural phenomenon. Officially known as 5Pointz Aerosol Arts Center, the warehouse turned outdoor exhibit space was considered the world’s premier graffiti mecca. Artists from around the world left their signature tags and artwork on the Long Island City factory building’s 200,000 square feet of façade space. The gallery’s curator had planned to turn the site into an official museum and education space for aspiring aerosol artists, but he never got the chance.

Rendering © HTO Architect

Rendering © HTO Architect

When the building owners announced plans to bulldoze the 5Pointz building and put residential towers in its place, artists banded together to seek landmark protections for their canvas. They even filed a lawsuit against the destruction of their artwork. But in November 2013, the building was horrifyingly whitewashed overnight. Then, this past summer renderings were revealed of the nondescript towers that will replace the once-exuberant arts space, which was ultimately demolished. Now, the 5Pointz artists are fighting against the developers who want to trademark the iconic 5Pointz name and use it for the towers.

Think we should have added a crime or two? Let us know your most-hated felonies in the comments!

Images courtesy of Wiki Commons and Google Maps unless otherwise noted

RELATED:

- Architectural Saviors: NYC Landmarks Saved From Destruction

- First Look at MCNY’s New Exhibit ‘Saving Place: Fifty Years of New York City Landmarks’

- City Launches Educational Website to Mark the 50th Anniversary of the Landmarks Law

- Preservationists Publish Report Asking City to Better Protect Soon-To-Be-Landmarked Buildings

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

When I see 5POINTZ’s replacement, I understand now that New York’s spot as an arts capital was fleeting m,aybe from 1950 – mid 1980’s. The city government is in the hands of developers and though I understand you have to build something to attract a wide variety opf tenants, is this really the best that can be done? We really are repeating the mistakes of the past and I am becoming more assured we will return to the fiscal crisis of the 70’s. Why? Well the city with enough of these bland towers will lose its attraction and there are plenty of...

Read moreHow about the miserable state of the Coney Island Shore Theater! You have to add this to the list! The building is in the news this week as the property owner Jasmine Bullard refuses to look at offers for the property and seems like she is hoping for a demolition by neglect judgment. This needs all the attention it can get, windows have been ripped out of the building the past few weeks and the theater looks in worse shape than ever. Here is our forum thread discussing the landmarked theater – http://community.coneyisland.com/cgi-bin/yabb/YaBB.pl?num=1405621081 Daily News article with pictures of interior from this Summer –...

Read moreRKO Keiths in Flushing and Richmond Hill. Please include this poor pair. And Yankee Stadium, Polo, and or Ebbets.

Finley student center at the city college of ny. Romanesque revival, demolished in 1986.

Hey you guys are missing the American Folk Art Museum that was demolished by the developer owned MoMA.

I used to be the music director of St. Ann’s Church on East 12th Street. The acoustics were marvelous for music, and the organ was the historic Erben organ with a wonderful sonority favored in the late 19th century. The congregation eventually dwindled to nothing.

Some of these vacant churches would make wonderful community centers, or open ‘flea markets’ that would be enjoyed and useful to the surrounding neighborhood.