The Meatpacking District: From the Original Farmers’ Market to High-End Fashion Scene

Why is it called the Meatpacking District when there are only six meat packers there, down from about 250? Inertia, most likely. The area has seen so many different uses over time, and they’re so often mercantile ones that Gansevoort Market would probably be a better name for it.

Located on the shore of the Hudson River, it’s a relatively small district in Manhattan stretching from Gansevoort Street at the foot of the High Line north to and including West 14th Street and from the river three blocks east to Hudson Street. Until its recent life as a go-to high fashion mecca, it was for almost 150 years a working market: dirty, gritty, and blood-stained.

Meat packing was only the latest of many industries based in the area. For decades it was a market hosting farmers from miles around who came to sell their wares, much as they do today in farmers’ markets across the city. Farmers started gathering in the 1860s, migrating from overcrowded markets farther south. They set up at the corner of Gansevoort and Greenwich streets, spontaneously creating the Gansevoort Farmers’ Market.

Gansevoort Street has a pretty interesting history itself. It was originally an Indian footpath to the river, following the same route it has today. In the 18th and 19th centuries it was known variously as Old Kill, Great Kill and Great Kiln road. A kiln—pronounced at the time and in some quarters still with a silent “n”—was an oven or furnace, which in this case burned oyster shells to reduce them to mortar, an essential ingredient for the bricks-and-mortar building trade.

In 1811, expecting a war with Britain, the city created landfill at the foot of Old Kill and erected a fort there. It was called Fort Gansevoort in honor of a Revolutionary War hero, Peter Gansevoort, who much later became the grandfather of the author Herman Melville. The street was renamed for the fort in 1937, even though the fort had been pulled down 90 years earlier.

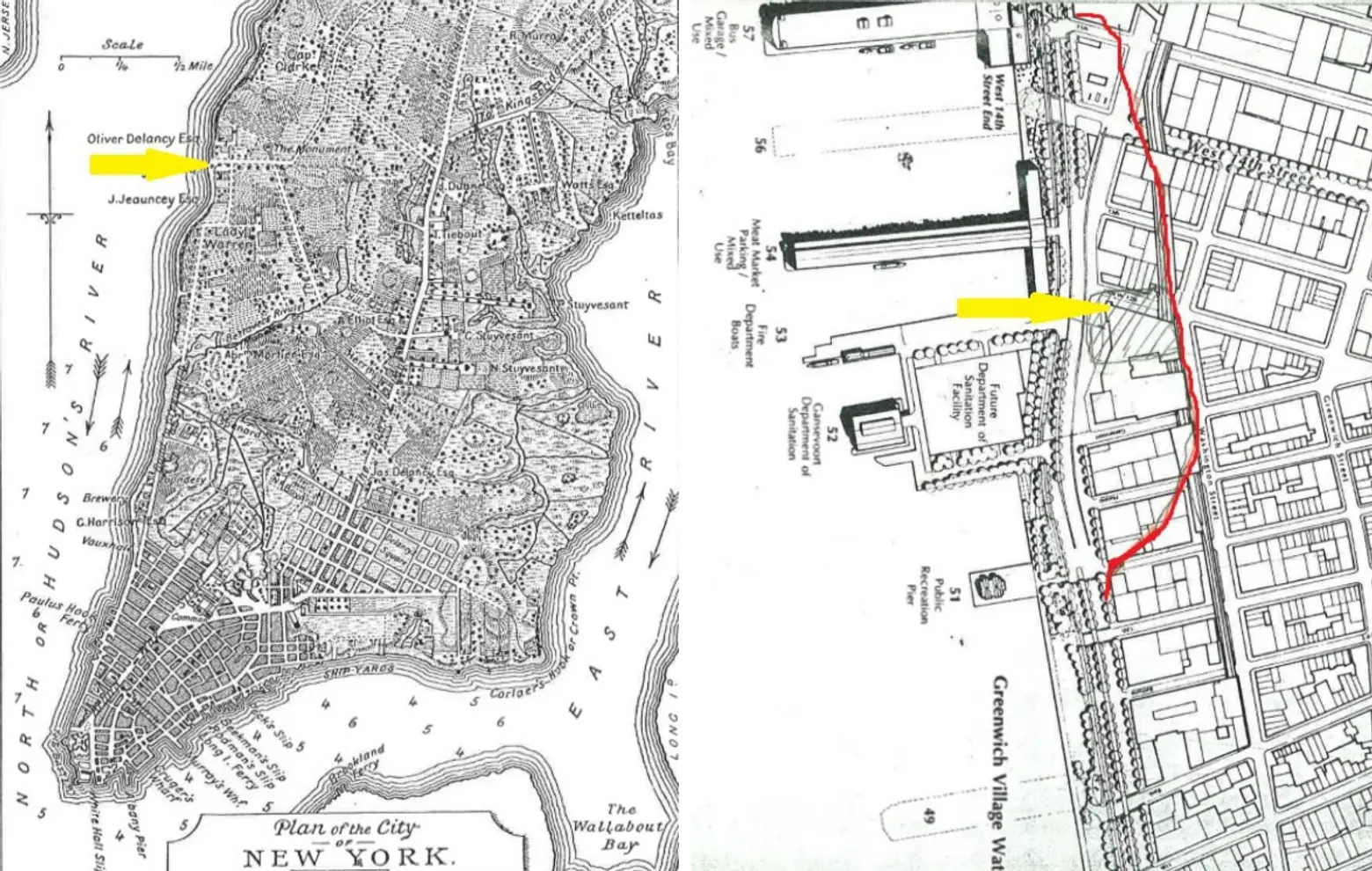

A map from 1767 that shows the Manhattan shore before landfill (L); A map that outlines (in red) where the landfill was added (R); the yellow arrows show the Fort Gansevoort site

A map from 1767 that shows the Manhattan shore before landfill (L); A map that outlines (in red) where the landfill was added (R); the yellow arrows show the Fort Gansevoort site

In the early 1830s, the Hudson River shoreline ran along Washington Street north of Jane Street, jutting out where the fort stood. The city wanted to expand landfill along the shore to encompass the fort and use the site for a market—an idea it had in mind since 1807. A major frustration was John Jacob Astor, a wealthy landowner, who owned that underwater land and refused to sell at a price the city considered fair. Astor was no fool. That land was chock-a-block with oyster beds, and New Yorkers ate oysters at the rate of about a million a year.

An 1854 map that shows the lumber (yellow), coal (red) and stone (blue) yards

Elsewhere, construction began in 1846 on the Hudson River Railroad with a terminus planned on Gansevoort Street for a train yard and freight depot. The fort was leveled at that time in order to accommodate it. The writing was on the wall for Mr. Astor and in 1851 he did sell his underwater land and the city created landfill extending all the way up to Midtown and farther. West Street and beyond it, 13th Avenue, were created, and farmers moved west to share that land. Piers, docks and wharves were built in the river–an 1854 map shows lumber, coal and stone yards on both sides of West Street. Exactly when meat marketers joined the farmers is not known, but most likely it happened little by little over time.

The 9th Avenue el in 1876, the smokestack from the kiln is visible in the background if you look closely

The 9th Avenue el in 1876, the smokestack from the kiln is visible in the background if you look closely

With all the industry on the river, there was lots of activity there and a need for better transportation. The 9th Avenue el was built in the late 1860s to bring in produce and people who commuted to the area. Residential construction was undertaken for the increased numbers of workers, modest houses four and five stories high. Also in the late 1860s the Hudson River Railroad abandoned its train yard, and the market took over that space entirely.

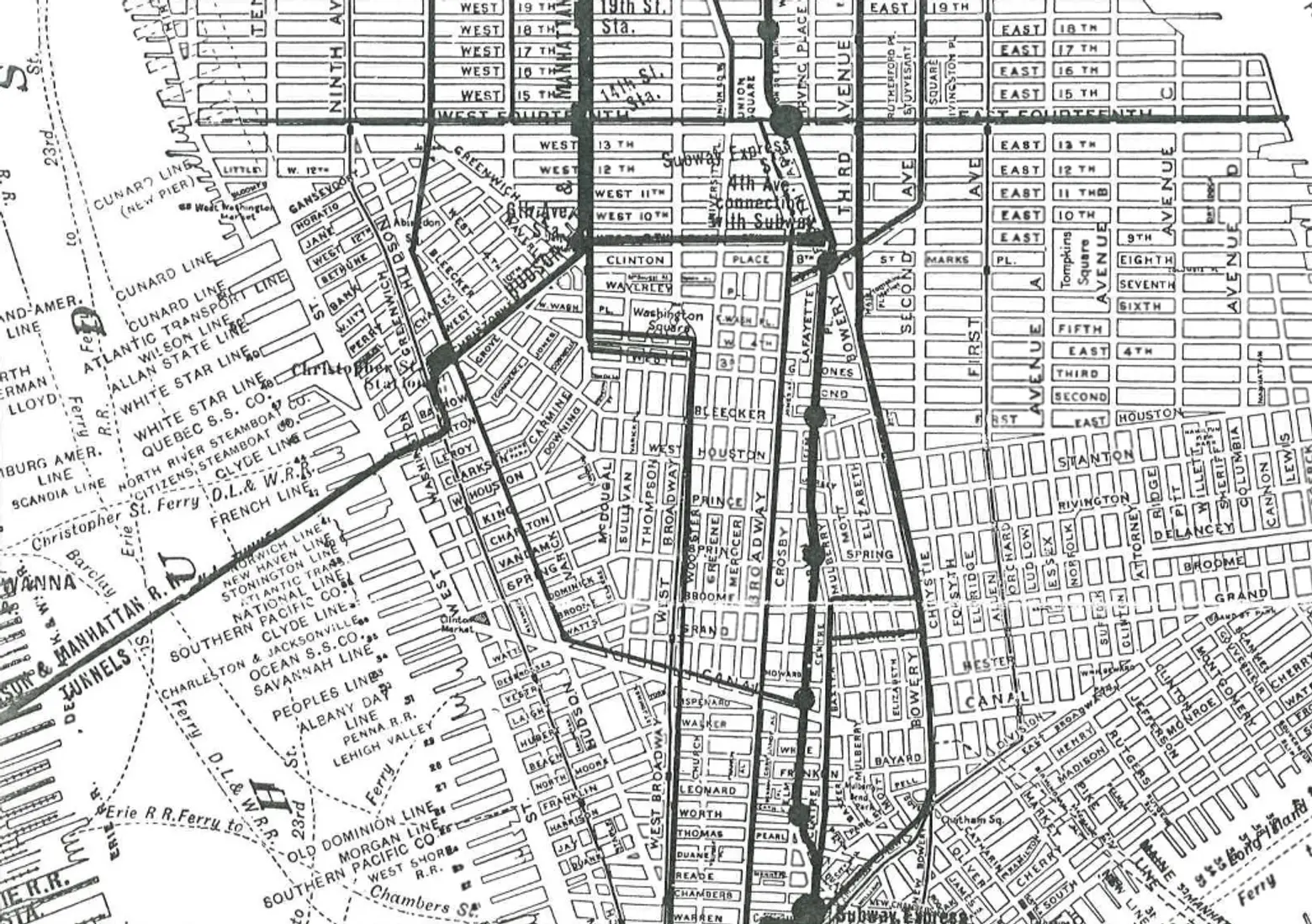

Wagons packed into Gansevoort Market in 1898

Wagons packed into Gansevoort Market in 1898

An article in Harper’s Weekly in December, 1888 noted that between 1,200 and 1,400 wagons in spring and summer “pack the square and overflow on the east as far as Eighth Avenue, on the north to 14th Street on 9th Avenue, and to 23rd Street on 10th Avenue, on the Gansevoort Market nights.” Crowded doesn’t begin to describe it.

In 1889 the city built West Washington Market, wholesale facilities for meat, poultry, eggs and dairy products across West Street on 13th Avenue to rent to farmers. More wholesalers applied for space than could possibly be accommodated, and the situation became even more frenetic the following year when brine-cooled water began to be pumped under West Street to provide refrigeration.

About 30 of the houses built in the area didn’t last very long, but were reduced over a period of about 50 years starting in the 1880s, knocked down to two or three stories. Sometimes two or three houses were joined, and instead of front rooms, kitchens, sitting rooms and bedrooms, the houses were gutted to create large interior spaces in which food could be handled and people could work. Once party walls were removed, those large open spaces could not support upper stories, so they were taken down to allow the load to meet capacity and the buildings were altered to two or three floors—offices upstairs—becoming what you see now as the characteristic building type in the district.

To many of those buildings, canopies were added with hooks on conveyor belts so that carcasses, when they were delivered (the animals were slaughtered and skinned elsewhere) could be loaded on the hooks and trundled inside, where they were dressed, i.e. cut into chops and roasts for retail sale. Those canopies—minus the hooks—are considered a characteristic feature of the district and remain.

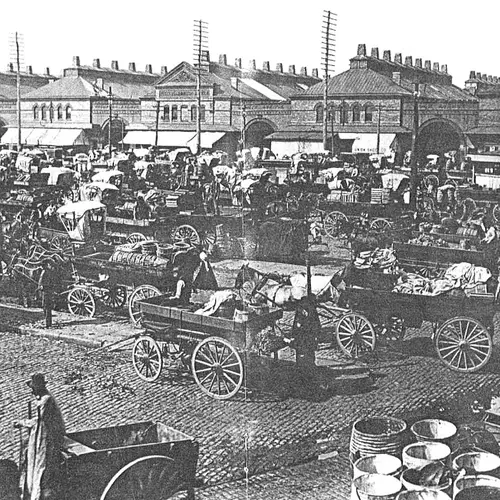

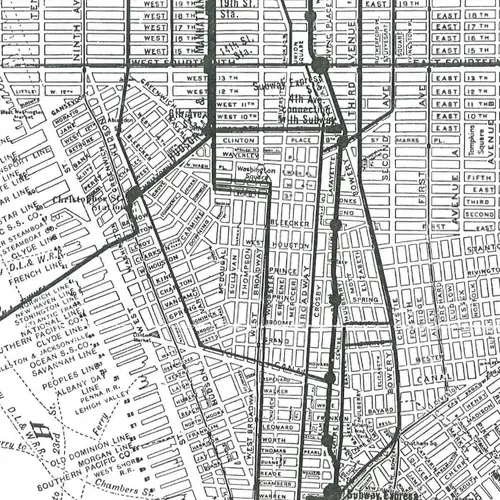

A 1905 map showing the many ship ports

A 1905 map showing the many ship ports

Early in the 20th century, technology enabled the building of steamships and ocean liners with greater load capacity, which in turn meant deeper drafts. Nineteenth-century landfill obstructed them, so, rather than lose lucrative docking tariffs to competing ports, New York City dredged the same landfill it had created, allowing the new ships to enter and demolishing 13th Avenue in the process. That’s why you don’t see it any more.

Renzo Piano’s new Whintey Museum via Timothy Schenck

The disadvantages of the Gansevoort Market were beginning to be felt in the late 1930s. For one thing, organized gangs were extorting money for good spaces, or any space at all, and it was pretty much impossible to move around. For another, 99-year warehouse leases began to expire. When they could, farmers migrated to other markets farther downtown, in Brooklyn or the Bronx. Some farmers continued to sell produce across West Street until mid-century, but they didn’t pay the city much for their stalls. Meat marketers paid more, and possibly for that reason, the city made plans to build special market buildings for them and turn the Gansevoort Market into a city-wide meat distribution center. It was finished in 1950, occupying city-owned land where Fort Gansevoort had stood. It was demolished very recently for the new Whitney Museum, which is almost finished, the third major piece of construction in 200 years to occupy the site of the old Fort Gansevoort.

A controversial glass addition coming to the Meatpacking District

A controversial glass addition coming to the Meatpacking District

In the 1960s produce marketers turned to the Hunts Point Terminal Market, which the city had built in the Bronx, brand new and more accommodating than the crime-filled and maddeningly congested streets around Gansevoort. Customers like to do all their shopping in one place, and restaurateurs, supermarkets and small retail shops helped make the Hunts Point Market a success. Meat marketers one by one finally joined their fellow food producers in the Bronx starting in the 1990s, and that is why there are so few meat packers left in the Meatpacking District.

The Gansevoort Market Historic District today, via CityRealty

The Gansevoort Market Historic District today, via CityRealty

In 2002 the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the meatpacking district as the Gansevoort Market Historic District, and many other types of businesses, especially those in the high-end fashion world, began to headquarter there. Those little two story buildings have been altered once again to accommodate new market uses, and life goes on. In some cases, life goes on as before; just last year, a new “Gansevoort Market” food hall opened on Gansevoort Street.

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

I have completed a history of Ottman & Company, one of the oldest and largest meat purveyors in the meatpacking district. Happy to speak with anyone who’s interested to learn more.