Home and Away: Is Airbnb a Threat to the Affordable Housing Market?

Photo courtesy of Airbnb via Facebook.

Controversial room-sharing startup Airbnb, one of the most visible players in what is being called the “sharing economy,” has recently awakened the innovation vs. regulation argument in all the usual ways–and a few new ones, including the accusation that these short-term rentals are depleting the already-scarce affordable housing stock in pricey metro areas like San Francisco and New York City.

Image: Sharyn Morrow via Flickr.

Image: Sharyn Morrow via Flickr.

It’s a relatively new business model, though most are familiar with it by now. Services like Airbnb, Vrbo and FlipKey offer an online platform where guests can book rooms in hosts’ homes or entire houses or apartments. Social networks like Facebook are used to post reviews to vet both hosts and guests.

Some hosts use the resulting income to help make rent–and make ends meet–in cities where housing costs are sky-high and growing. Others use the platform as a profit-making enterprise, on a scale varying from a room or two to entire buildings used for the purpose. In many cases, guests say they’re getting a much better cultural experience than if they stayed in a hotel. Rooms often cost far less than those in city hotels, allowing more frequent travel and longer stays.

Airbnb founders (l-r) Joe Gebbia, Nathan Blecharczyk, Brian Chesky.

Among these companies, Airbnb is by far the largest and most recognized. The San Francisco-based company operates in thousands of cities internationally. Valued at $10 billion, the company raised over $450 million from investors last April. Using a business model that is more peer-to-peer (think Napster, Etsy and eBay) than traditional business/consumer model, the company says it’s part of an “invisible economy” of micro-entrepreneurs. In this case, though, the commodity up for grabs is (almost) literally the roof over our heads.

Those who have expressed growing opposition to the Airbnb business model include the hotel industry, housing advocates and local elected officials. The hotel industry points to the fact that they collect and pay the city a transient occupancy tax for the service they provide; Airbnb, their biggest and growing competition–according to a NY Attorney General’s report based on Airbnb data, the company’s top 40 hosts in New York City have reportedly grossed more than $35 million combined–historically has not, although they have recently agreed to do so in some cities including NYC, San Francisco and Portland, OR.

Cities like NYC and San Francisco are unique in that they have a highly competitive real estate market, a large number of multi-family dwellings, a low vacancy rate and the presence of rent-regulated housing. Housing advocates point to recent data as proof that a growing number of dwellings are being removed from the pool of available rental housing, citing multiple properties that are being leased to guests by single owners via Airbnb. Further concerns include the potential dangers–and quality-of-life issues–of using unlicensed and unregulated facilities as guest quarters.

One of the many large-scale users of Airbnb: Networks of communal crash pads for coders like this San Francisco International Hacker Hostel, which (legally) uses a long-standing neighborhood international hostel, mix co-working with bnb-ing.

In September, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a law permitting and regulating short-term stays–the previous law was similar to NYC’s in that it prohibited most residential rentals of 30 days or fewer. The controversial legislation was meant to balance the desire of Airbnb hosts to rent out their homes with the need to regulate the activity, prevent it from affecting the availability of housing and maximize its benefit to the city. The legislation limits hosting to 90 days per year, requires hosts to register with a public registry and to pay hotel taxes levied by the city on guest stays booked via Airbnb. The new law also limits this type of home-sharing to full-time residents to keep landlords from using housing stock for short-term rentals and removing it from the rental market. Housing interests opposed the law, saying that it would make an extremely tight rental market worse than it already is (more from CNet).

In NYC, Attorney General Eric Schneiderman made headlines when he announced a new round of enforcement efforts against what he claims are illegal hotels, referring to Airbnb users–as many as two-thirds of them according to the AG’s office–who are in violation of the 2011 law that prohibits apartment rentals lasting fewer than 30 days without the primary resident present. The law was created to prevent the practice of the city’s apartments being used as ad hoc hotels.

In a tight rental housing market, the main concern is that the lucrative lure of Airbnb income–you can make more money renting out an apartment every night for $150 compared to what you could get in monthly rent–could reduce the number of units on the rental market, lead to evictions and cause rent hikes across the board.

At worst, landlords could evict or refuse to renew the leases of market rate tenants in favor of short term guests, though evidence of this particular phenomenon is mostly anecdotal at this point. The new San Francisco law addresses this possibility, but it isn’t clear whether the New York law–which, for example, does not apply to one- and two-family dwellings–goes far enough to provide protection or recourse against it.

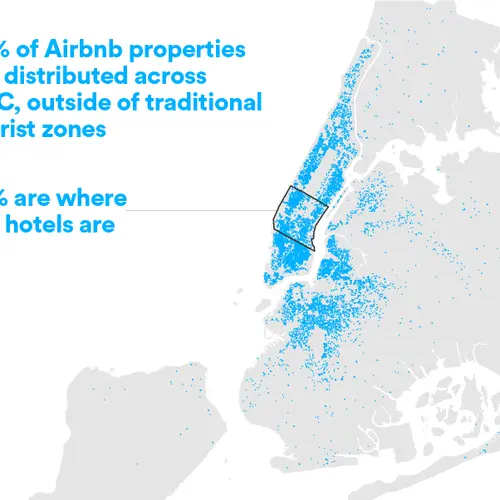

Airbnb insists that it actually helps make city living affordable for hosts. The company also points to the fact that the availability of home-sharing allows travelers to visit the city more and for longer stays, which leads to tourist revenue and other economic pluses. Marc Pomeranc, public policy manager at Airbnb, cites the statistic that 87% of Airbnb hosts only share the home in which they live, and only on an occasional basis.

Image: Airbnbnyc.

Airbnb has agreed to put tax revenue back into the cities in which it operates. The company recently announced its intent to collect and pay hotel taxes in New York City and San Francisco; they already pay hotel taxes in Portland, OR. The company projects that it will generate $768 million in economic activity in New York in 2014 as well as $36 million in sales tax.

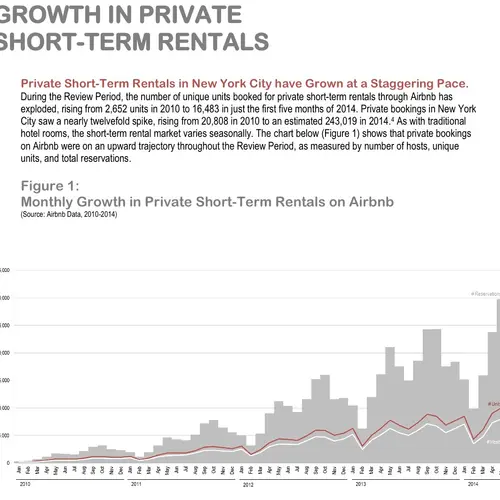

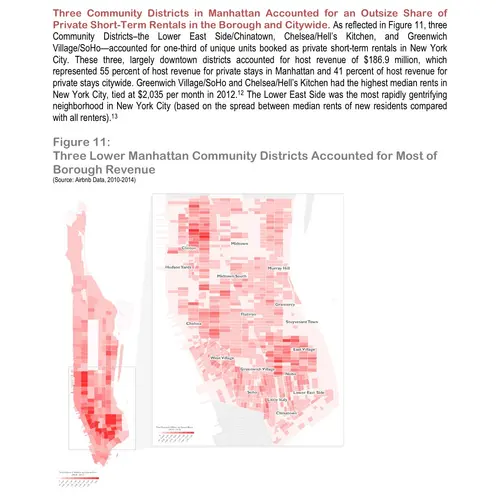

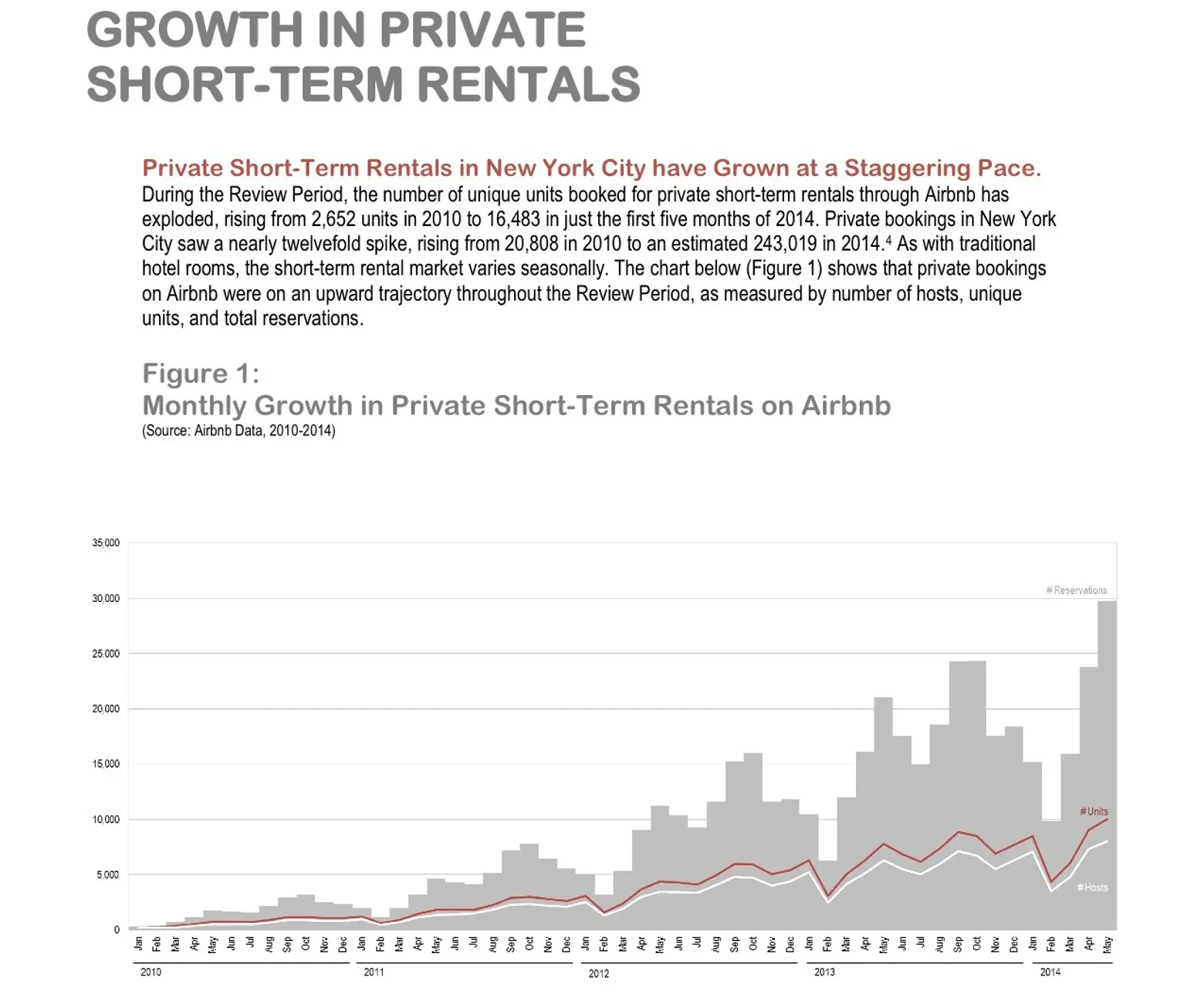

Source: Airbnb in the City, a report from the office of New York State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman.

A flurry of recently-obtained data has uncovered some interesting insights: Unsurprisingly, New York represents a major market for the company with 19,521 listings as of Jan. 31, according to studies done by data firms Skift and Connotate. Thirty percent of rentals come from people with more than one listing–a total of 1,237 NYC listings.

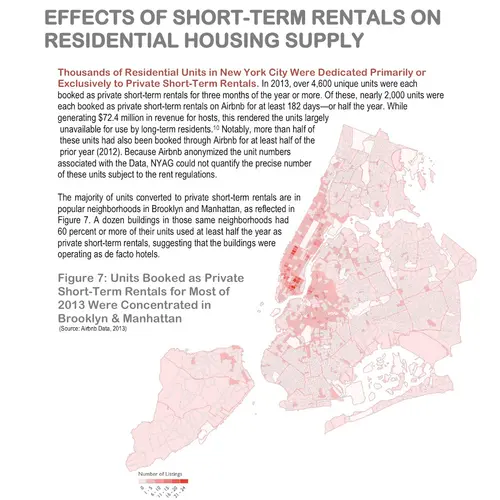

Source: Airbnb in the City, a report from the office of New York State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman.

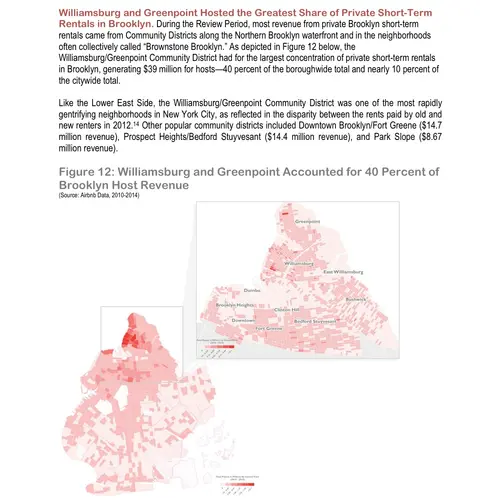

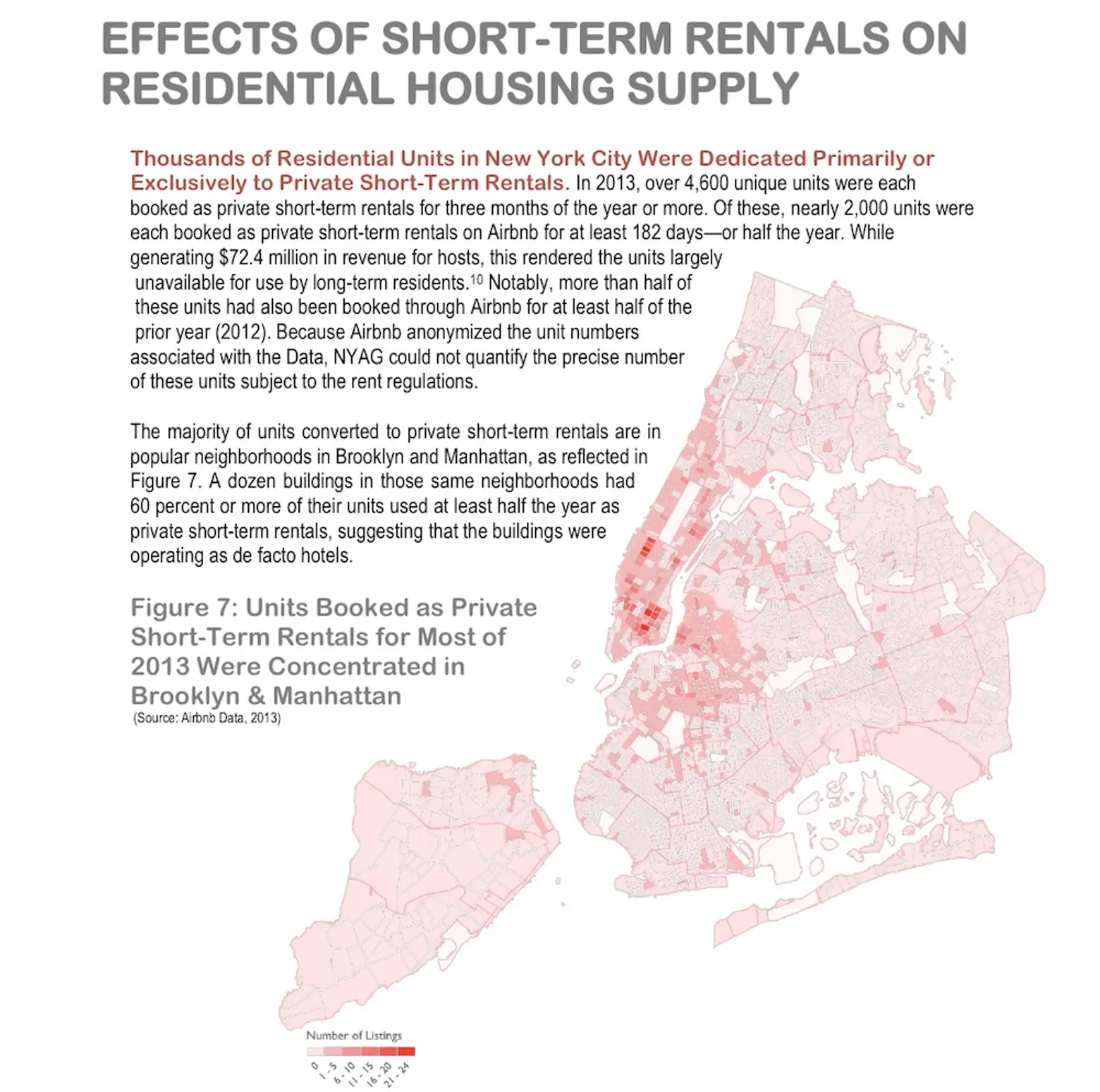

According to a report commissioned by the Attorney General’s office and released in October, at least 4,600 units were booked in 2013 for at least three months. Of these, nearly 2,000 were booked for a cumulative total of over six months; the percentage of host revenue from units booked as short-term rentals for more than half the year increased steadily, accounting for 38% of the site’s revenue by 2013. The report summary cites this as evidence that “short-term rentals are displacing long-term housing options.” During the period studied, the top Airbnb commercial operator in NYC had 272 listings and made $6.8 million in revenue.

Source: Airbnb in the City, a report from the office of New York State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman.

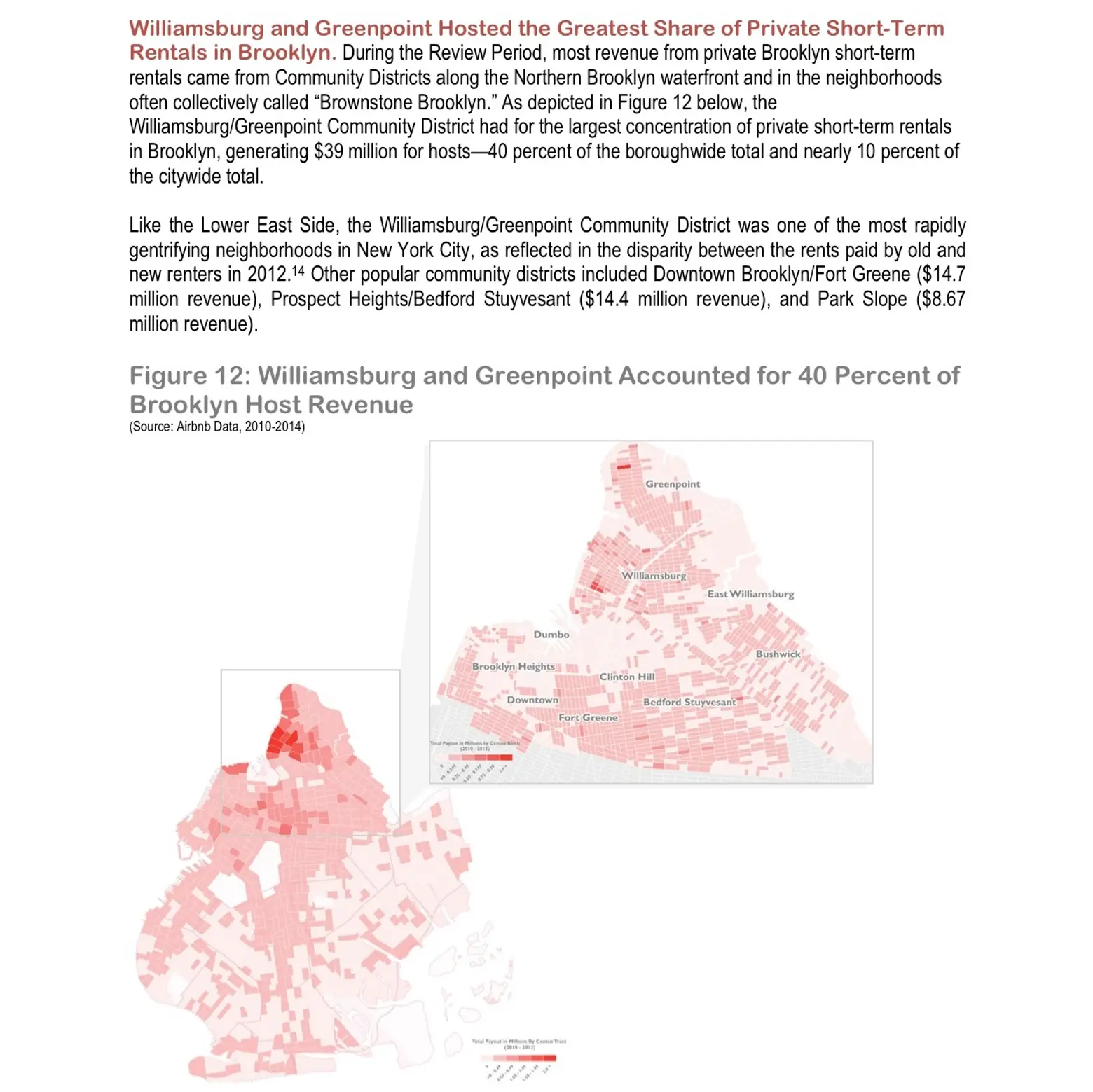

The report found a high concentration of Airbnb usage in the city’s most desirable and expensive residential Manhattan neighborhoods like the Upper West Side and Greenwich Village, in addition to high concentrations of Airbnb usage in neighborhoods like Bed-Stuy, Harlem and Williamsburg, where double-digit rent increases are forcing out longtime residents. In a statement that accompanied the report, Schneiderman announced a joint city and state enforcement initiative “aimed at aggressively tackling this growing problem.”

Though it indicates interesting trends in the way we’re doing business, this new batch of Airbnb data can be misleading. Both sides of the argument have focused on different numbers to make their case. At this point, the rapid expansion of Airbnb may well be more a symptom of the low supply of affordable housing than a significant cause.

Bed-Stuy brownstones.

Far more relevant forces predate the so-called sharing economy. To put things in perspective, New York City lost 40% of its affordable housing units in the last decade according to a study by the Community Service Society, a NYC poverty-fighting group. The study points to the ability of landlords to raise rents to market rate after renovating rent-regulated apartments and rapidly increasing rents in gentrifying areas as the main forces driving this loss.

Manhattan’s top tier of luxury developments. One57 (l), 432 Park Avenue (r).

The 21st century gold rush of new residential development continues apace, even if the abundance of new housing costs far more per night than the average Airbnb rental. The proliferation of multimillion-dollar luxury apartments that out-of-town owners use as pieds-à-terre as recently discussed in the New York Times–meaning they sit empty much of the time–continues as investors seek safe alternatives to uncertain international markets; this does nothing to change the affordable housing equation. Acres of land that remain unused year after year while developers sue each other, petition the city for zoning changes and haggle over the right to build as little affordable housing as possible also fail to address the growing problem.

Northside Piers Williamsburg Condo.

A recent discussion in the SF Chronicle quotes Gabriel Metcalf, executive director of SPUR, an urban design think tank, “From a policy perspective, the real issue is whether there are a lot of units that have been removed from the housing market because of short-term rentals. It looks like that’s not a big number yet, but that’s what we need regulation to control so it doesn’t become big.”

When innovation happens in business, regulation is often left playing catch-up. Airbnb has lawmakers scrambling in many different areas including tax revenue, public safety and housing law. Regulators will need to figure out how to monitor, regulate and enforce, and Airbnb may have to change its business model to comply. New rules are required in order to strike a balance between encouraging innovation and safeguarding the public interest.

Airbnb San Francisco HQ. Image: Rasmus Andersson via flickr.

Want more numbers?

- Get a closer look at the Attorney General’s October report documenting “Widespread Illegality Across Airbnb’s NYC Listings,” below. You can find the press release and the original report here.

- The SF Chronicle reveals some fascinating facts about the top San Francisco Airbnb hosts (by listings) and other goings-on.

- Skift study on Airbnb in NYC.

“Knock it Off“–Video by anti-Airbnb group Share Better.

http://youtu.be/ryqdC7bNidk

“Meet Gladys & Bob“–Airbnb says hosting supplements incomes and enriches neighborhoods.