Peeking into the East Village’s Marble Cemeteries

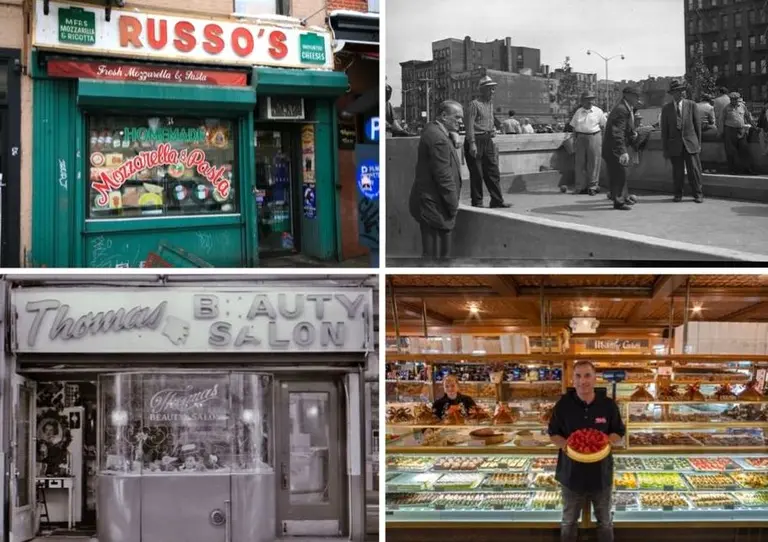

Today we think of cemeteries as spooky, haunted places that we avoid, or as sad, depressing spots reserved for funerals. But they were once quite the opposite–in fact, they were the earliest incarnations of public parks. In New York City, burials took place on private or church property up until the mid-1800’s when commercial cemeteries began popping up. And in the East Village there are two such early burial grounds hidden among the townhouses and tenements–the New York Marble Cemetery (on the west side of Second Avenue just above Second Street) and the New York City Marble Cemetery (on the north side of Second Street between First and Second Avenues).

Though their titles are extremely similar and they’re located less than a block apart, the two cemeteries are operated separately and have their own unique history. And during openhousenewyork weekend, we were lucky enough to take a peek beyond the cast iron gates and into these important pieces of the East Village’s past.

New York Marble Cemetery

Entry gate on Second Avenue via wallyg via photopin cc

Entry gate on Second Avenue via wallyg via photopin cc

The New York Marble Cemetery was founded in 1830 as the city’s first non-sectarian, public burial ground. Perkins Nichols developed the cemetery as a commercial undertaking, brought on by yellow fever and cholera outbreaks. People feared being buried just a few feet below ground, and public health legislation outlawed earthen burials. Therefore, Nichols saw a market for underground burial vaults. The location he chose is the interior of the block bounded by Second Street, Third Street, Second Avenue, and the Bowery. At the time, it was believed that Second Avenue would become the city’s fashionable residential street, but that title instead went to Fifth Avenue. The cemetery is accessed through an alleyway with a decorative iron gate at each.

Marble vault markers on the stone wall via gsz via photopin cc

The underground vaults were very unique for the time. Made of solid, local Tuckahoe marble, they’re the size of small rooms, have arched ceilings, and are situated ten feet underground. A stone slab set below the grade of the lawn marks and provides access to each vault. Marble was used as the material of choice since it was thought to prevent the spread of germs and diseases.

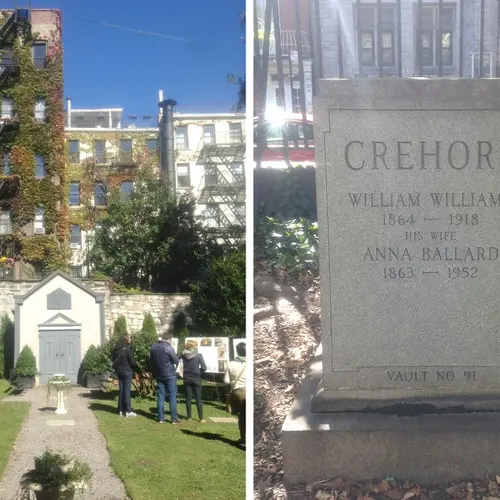

Instead of traditional headstones, the vaults are marked with Tuckahoe marble plaques set into the cemetery’s long north and south walls. They provide the name of the original vault owner and the nearby family members, as well as indicate each vault’s exact location.

There are a total of 156 subterranean tombs in the New York Marble Cemetery, in which about 2,100 persons have been laid to rest–the first in 1830 and the last in 1937. Nearly half of the earliest caskets held children ages six and under who had died from diseases that we now fight with vaccines and antibiotics. At the end of the 19th century, when it was clear that the Second Avenue area did not become the trendy community everyone had hoped for, many remains were removed and relocated by family members to more spacious, rural cemeteries like Woodlawn and Greenlawn.

Most of those buried in the half-acre cemetery were from prominent professional and merchant families, including publishers Uriah and Charles Scribner; Aaron Clark, New York City’s first Whig mayor; arts patron Luman Reed; Benjamin Wright, chief engineer for the Erie Canal; and James Tallmadge, Jr., Congressman and NYU President. Additionally, members of some of New York’s oldest and most well-known families, such as the Varicks, Beekmans, Van Zandts, Hoyts, and Quackenbushes have vaults.

Aerial view of a wedding in the cemetery via Heron and Hummingbird

Aerial view of a wedding in the cemetery via Heron and Hummingbird

Today, the descendants of those who purchased vaults in the 19th century still own and are entitled to use the vaults. The owners are invited back each spring for the Annual Reception. The cemetery is an official non-profit organization, a New York City landmark, and on the National Register of Historic Places. It’s open to the public during its Open Gate Days, held once a month in the spring and summer, and every year during OHNY. The New York Marble Cemetery can also be rented for weddings, fashion shows, and film shoots.

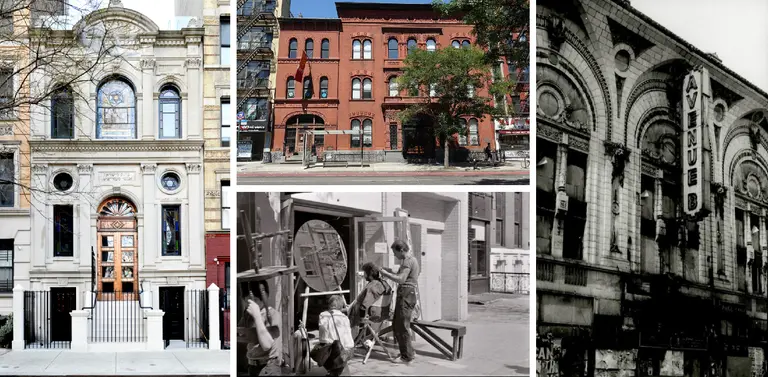

New York City Marble Cemetery

Iron fence and gate along Second Street via warsze via photopin cc

Iron fence and gate along Second Street via warsze via photopin cc

Nichols saw such success at the New York Marble Cemetery that he embarked on a second, larger marble-vaulted venture around the block in 1831, funded by a group of wealthy New Yorkers. It was laid out on land owned by Samuel Cowdrey, a vault owner in the first cemetery.

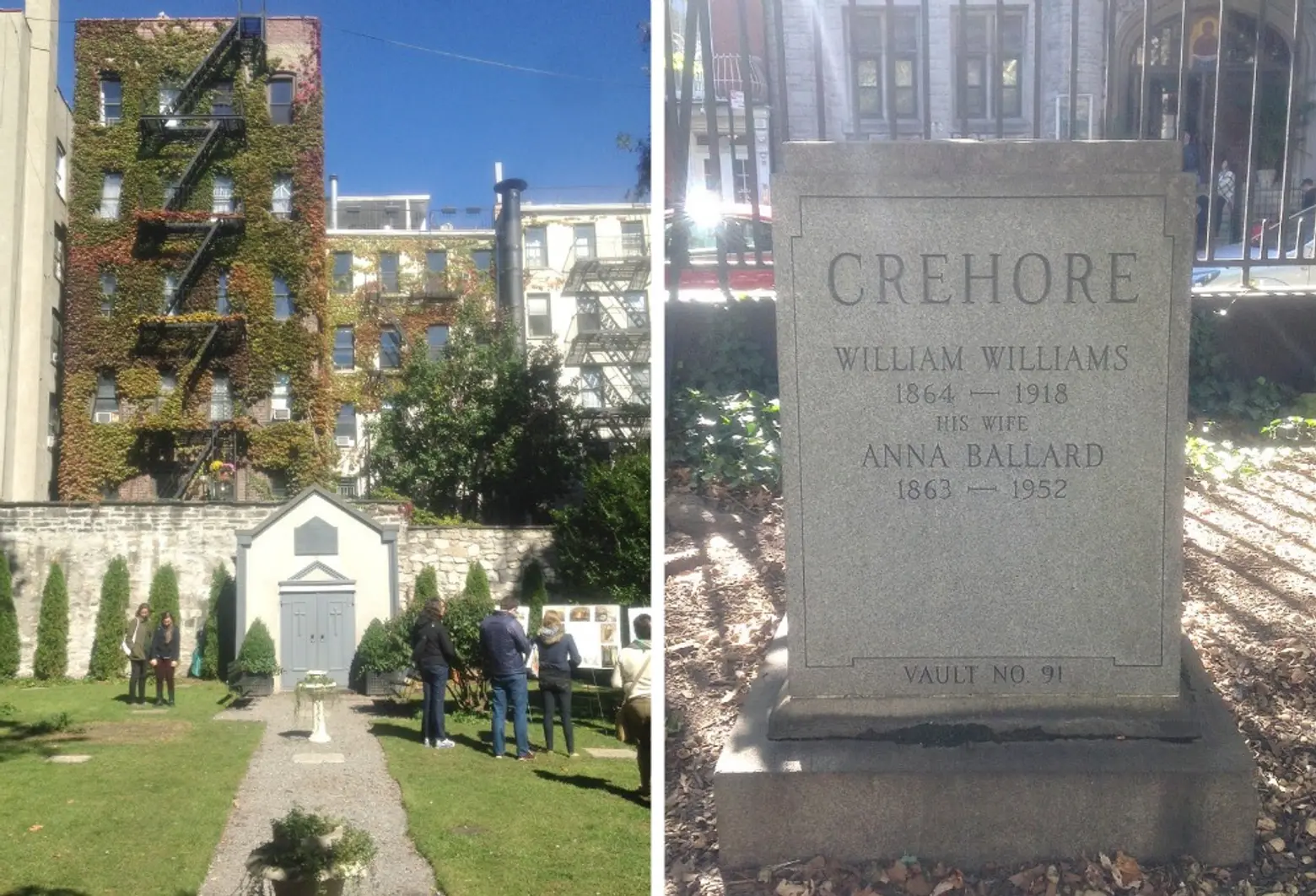

The New York City Marble Cemetery was also non-sectarian and open to the public. Unlike its neighbor, though, it is visible from the street and stretches across several lots on the block, set behind an iron fence with gate. The vault markers are laid out in narrow strips along the ground, punctuated by various handsome, upright monuments.

Via edenpictures via photopin cc

Via edenpictures via photopin cc

Again, Tuckahoe marble was used to construct the 265 vaults. It’s not known exactly how many bodies lie here, but it’s estimated that there are between 4,000 and 5,000. The vaults are accessed through an underground antechamber that is reached by a ladder from an opening in the ground. This opening is covered by a granite stone, which is moved with a special tool. Once below ground, stone doors lead into the vault that likely has shelves on either side to hold coffins and urns.

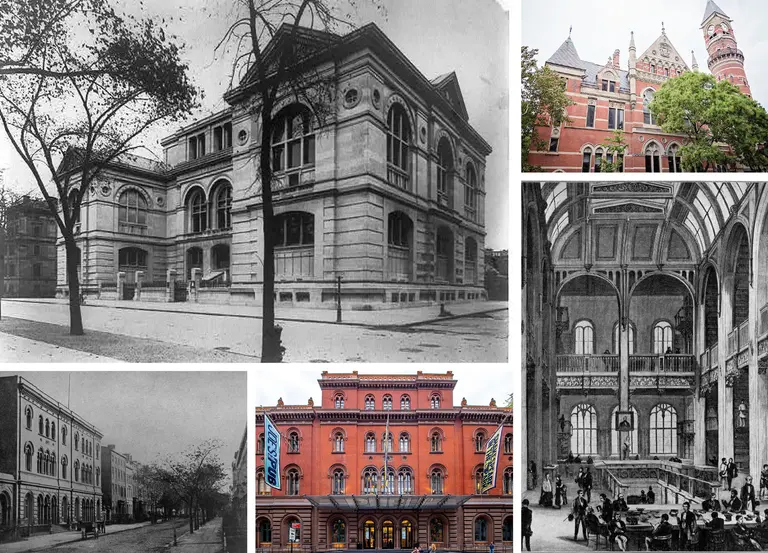

Notable “residents” of the New York City Marble Cemetery include James Lenox, who book collection helped form the New York Public Library; John Lloyd Stephens, the archeologist who pioneered the study of Mayan culture; James Henry Roosevelt, founder of Roosevelt Hospital; former New York City Mayor and New York State Governor Stephen Allen; New York City Mayor Isaac Varian; and the entire Kip family (of Kip’s Bay). President James Monroe was buried here in his son-in-law’s vault in 1831, but the State of Virginia relocated his remains to Richmond in 1858.

Just like the first Marble Cemetery, descendants of the original vault owners can be buried in the cemetery (five people have chosen to do so in the last ten years, in fact) and it is both a New York City landmark and on the National Register of Historic Places.

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Very interesting