New Yorker Spotlight: Eloise Hirsh on Turning the Freshkills Landfill Into a Thriving Park

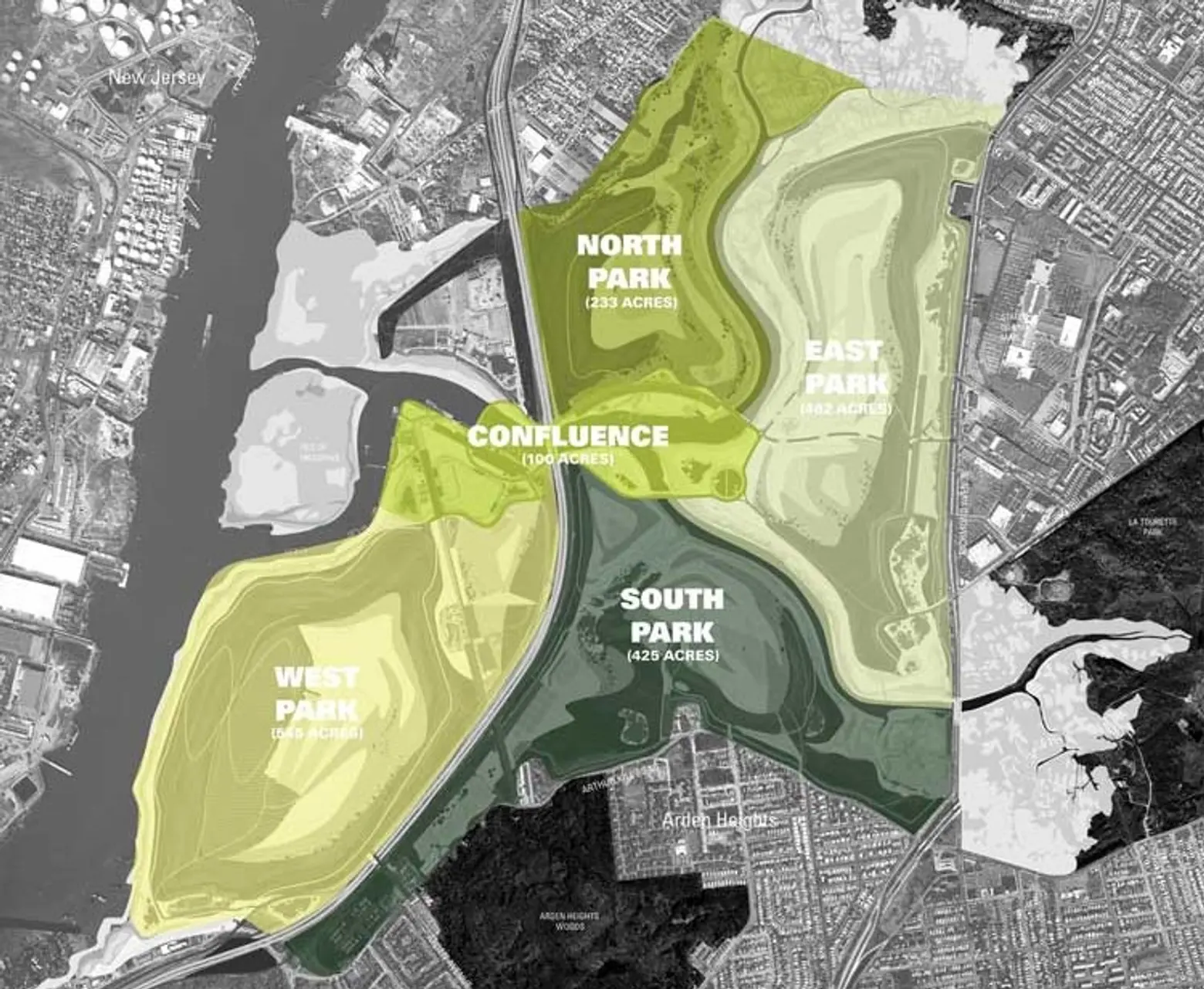

Similar to Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s grand ideas for Central Park, there is a vision for the 2,200 acres of reclaimed land at the former Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island. Where trash once piled up for as far as the eye could see, the site is now a blossoming park full of wildlife and recreational activities.

The Park Administrator overseeing this incredible transformation is Eloise Hirsh. Eloise is a major force behind the largest landfill-to-park conversion in the world to date. In her role as Freshkills Park Administrator, she makes sure the park progresses towards its completion date in 2035, and regularly engages with New Yorkers to keep them informed and excited.

6sqft recently spoke with Eloise to learn more about Fresh Kills’ history, what it takes to reclaim land, and what New Yorkers can expect at the park today and in the years to come.

Fresh Kills in the 1940’s (L); Fresh Kills Landfill (R)

Fresh Kills in the 1940’s (L); Fresh Kills Landfill (R)

Most New Yorkers know Fresh Kills was once a landfill, but how it became one is often not discussed. Can you share a bit about its history?

Eloise: This section of western Staten Island was originally salt marsh and wetlands. Around the turn of the century, the borough was basically rural, and the western section was a site of small manufacturing with brick and linoleum makers. Robert Moses, New York’s master planner, had the idea of filling all this acreage with landfill because the city was growing and had a garbage problem. People had a very different concept of wetlands before 1950. They thought of them as places of pestilence and mosquito breeding. They didn’t understand their role as we have come to understand today, and instead thought they had to get rid of them.

Moses said the city would fill the area for two to five years, and then he had a plan for residential development on the east side of what is now the Staten Island Expressway and light industry on the west side. However, five years turned into ten, ten to 20, and 20 to 50, until finally all of New York City’s garbage was coming to Fresh Kills Landfill.

There used to be landfills all over the city, and parks and buildings were built on many of them. Flushing Meadows Park was a landfill, as was Pelham Bay Park and lots of coastline around Manhattan and Brooklyn. As the regulations got more stringent in the 1970’s and 80’s, the city decided to make a major investment to meet the regulations at Fresh Kills, and they gradually closed down the other landfills around the city. In the 90’s, Fresh Kills was a state-of-the-art engineered site; it met all the environmental protection regulations.

Why did the city decide to close the site?

Eloise: As you can imagine, the residents of Staten Island hated it, and they protested for years. It finally happened when there was both a Republican mayor and governor at the same time. A state law was passed in 1996 that required the Fresh Kills Landfill to cease accepting solid waste by December 31, 2001. In March 2001, the landfill accepted its last barge of garbage.

Why did the city decide to develop a plan to transform Fresh Kills into a park?

Eloise: When the closure was announced, Kent Barwick, who was the director of the Municipal Arts Society of New York at the time, went to then Mayor Rudi Giuliani and told him that this is the last time the city is going to get this much open land. An international competition was held, and architecture and landscape architecture firms from around the world entered. The competition was won by James Corner Field Operations as their first big project. From 2003 to 2006, the firm, in conjunction with the Department of City Planning, got lots of ideas about what the park should be. This master planning process yielded a Draft Master Plan in 2006. At that point, Michael Bloomberg was Mayor, and he gave the job of implementing that plan to the Parks Department.

Does the Draft Master plan allow for changes as the project moves along?

Does the Draft Master plan allow for changes as the project moves along?

Eloise: When the Draft Master Plan was developed, not everyone understood all the systems that were required and regulations that had to be followed. We are making changes as we go along for technical reasons and as community interest changes. People thought about tennis courts in the beginning, but now everyone wants soccer fields. Inevitably, something that takes this long will change gradually. We think of it as a guidepost; it gives everybody a general concept of what the park can be.

What was the ecological impact of the landfill?

Eloise: Most of the wetlands and marshy areas in between were filled, but the major waterways still exist. In fact, there is a stream that goes throughout the site. A way to describe what happened to the land is by discussing what’s coming back now. The thing that people most remember about Fresh Kills is what it smelled like. Now, it is 2,200 acres of extraordinarily beautiful landscape with hills and waterways going through. The wildlife has returned, and there are all kinds of birds, deer, groundhogs, and foxes.

This area of western Staten Island has a clay base, which is pretty impermeable soil, so there is a reduction in pollutants leaking. The Department of Sanitation placed containment walls around the landfill to prevent pollutants from leaking to adjacent areas.

What does the process of reclaiming land involve?

Eloise: First, it requires managing the two products that landfills make: leachate, the liquid that percolates through the decomposing trash and settles at the bottom, and landfill gas, half of which is methane. There are two state-of-the-art systems in place to manage both of those products. The leachate is collected through a series of pipes and transportation systems, and then is taken to a processing plant on site where the liquid is cleaned and the water purified. The solids are then sent to a different landfill, but not a toxic waste landfill. The gas is also processed at a plant on site. The methane goes directly into National Grid’s pipeline. The city makes money off it, and National Grid gets enough to heat about 20,000 homes on Staten Island. It’s a renewable energy process.

Then there is the covering system, which is a series of layers of different soils, geotextiles, and impermeable plastic, which is very thick and seals the trash. So, between the trash and the public there is an impermeable layer and two-and-a-half feet of very clean soil. The third part of reclaiming land is to manage the storm water. That requires engineering slops, which is what the Department of Sanitation has done. People come from all over the world to see this state-of-the-art process and what has to happen in order to reuse this much land.

How did you get involved in the reclamation project?

Eloise: This is my second time around in the Parks Department. During the Koch administration when Gordon Bay was the Parks Commissioner, I was First Deputy Commissioner. That was terrific and I loved it, but then I moved with my husband to Pittsburgh where I was the Director of City Planning. There, I worked on a lot of former industrial sites to turn them into urban amenities. When we came back to New York nine years ago, I heard about this project. It sounded like a good extension of my experience in Pittsburgh, and I thought it would be really incredible to work on it.

As Freshkills Park Administrator, what does your job entail?

Eloise: A big part of my job is to keep clear on the mission to make this park beautiful, accessible, and a unique experience for New Yorkers that demonstrates all aspects of sustainability and makes them think about recycling on the biggest possible level. I keep the project moving through all the inevitable roadblocks that come our way. Another important piece of my work is reaching out and building support for this very big project. The Freshkills Park Alliance is supporting our work to bring the park to the public in as many ways as we can, even before it’s open. I work closely with them, making sure our team is doing everything we can to grow the audience for this incredible regional asset.

This is a very complicated project that involves many city and state agencies. On the city side, there is the Parks Department and Department of Sanitation. There is also Environmental Protection, City Planning, Department of Transportation, and Design and Construction. On the state side, there is the Department of Environmental Conservation as well as State Parks, Department of State, and State Transportation. All these agencies control some aspect of what we are doing at Freshkills Park.

What is the role of Freshkills Park Alliance?

Eloise: The Alliance’s goal is to raise money, guide programing, and develop a scientific agenda. We plan events and education programs that make the park accessible as it’s being developed and support the scientific research that we want to have here. One of our hopes for the site is for it to be a place where we can demonstrate the ways you can deal with recovering damaged land.

How will this park change Staten Island?

Eloise: There are a lot of things going on in Staten Island right now, including the New York Wheel. This park will certainly change the public perception of the borough. A lot of people think when they hear Freshkills, “Oh, that’s where the dump is.” Now, it will be, “That’s where this fantastic park is.”

A rendering of bird watching at Freshkills

A rendering of bird watching at Freshkills

What are some of the unique recreational activities the park currently offers and hopes to offer in the future?

Eloise: We have a park and playground at the western end. We have soccer fields, and teams play there from 8:00 in the morning to 10:00 at night. One thing that is really unique is the expansiveness of the site. It’s almost three times the size of Central Park. Because of the topography, when you are up on these hills you get an incredible feeling. You could be in Wyoming, except you see New Jersey. We do offer hiking, and some day people will be able to wander on what looks like moors in Ireland. In the future, there may even be an opportunity for skiing.

I think people are starting to realize it’s real, which is exactly why having our sneak peak event on September 28th is so important. It allows us to open up the park and let people come and see its future. It’s why we have races, kayaks, and tours throughout the year. We want to make the site real to people and change their perception.

A rendering of horseback riding at Freshkills Park

A rendering of horseback riding at Freshkills Park

What has being involved in this project meant to you?

Eloise: It’s an incredible opportunity to be part of sustainability work. A very wonderful part of that work is my team. Everybody is so interested and driven by repurposing land, their personal responsibility for waste, and the opportunity to design this park. For me, it’s a joy to come to work with people who are so excited. Being part of something that has that energy and mission is quite wonderful.

***

[This interview has been edited]

Images courtesy of Freshkills Park Alliance

This Sunday, September 28th is Sneak ‘Peak’: Greenway Adventure at Freshkills Park. The public is invited to visit the park and participate in activities including kayaking, biking, and walking tours.

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

How wonderful that a mere guess would have turned up this great piece on Freshkills and Eloise Hirsh with whom I have lost contact for DECADES. I love Eloise and she is still an anchor in chaotic times. Her work inspires me in my donkey rescue, beekeeping and winery to keep thinking light is always out there! Kudos.