New Yorker Spotlight: Sara Cedar Miller and Larry Boes of the Central Park Conservancy

Sara Cedar Miller and Larry Boes

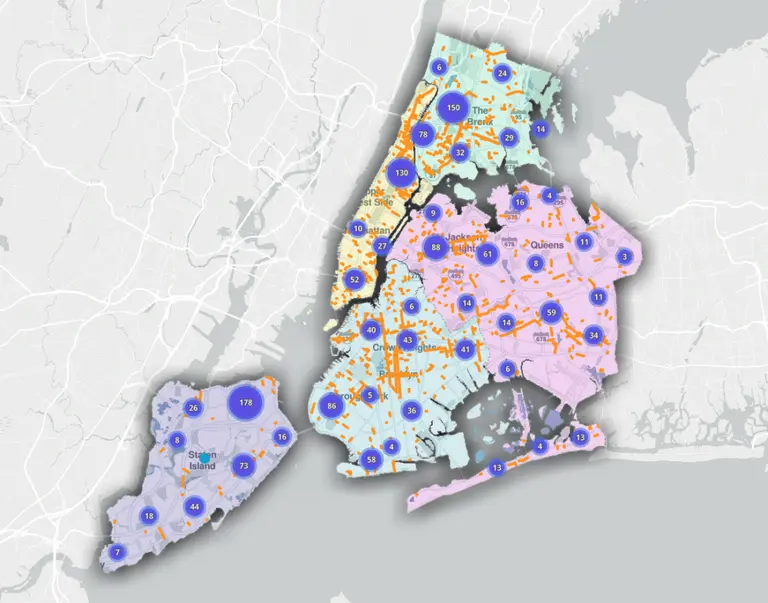

Central Park’s 843 acres serve as New York City’s backyard, playground, picnic spot, gym, and the list goes on. Taking care of the urban oasis is no small task; it requires gardeners, arborists, horticulturists, landscape architects, designers, tour guides, archeologists, a communications team, and even a historian. The organization in charge of this tremendous undertaking is the Central Park Conservancy. Since its founding in 1980, the Conservancy has worked to keep the park in pristine condition, making sure it continues to be New York’s ultimate escape.

Eager to learn more about Central Park and the Conservancy’s work, we recently spoke with two of its dedicated employees: Sara Cedar Miller, Associate Vice President for Park Information/Historian and Photographer, and Larry Boes, Senior Zone Gardener in charge of the Shakespeare Garden.

Sara, how did you become the Central Park Conservancy’s Historian?

Sara: I was hired as the photographer in 1984, and after a couple of years I asked for a raise. Betsey Rogers, who founded the Conservancy, said, “Yup, you’ve worked hard and that’s great, but we need to give you another title.” I replied, “Well, I do a lot of the historic research,” so she made me the historian. The minute I was a card-carrying historian, I started reading like crazy. I’ve written three books on the history of the park, which always include information about the Conservancy. I give tours, write, do lots and lots of fact checking on the park’s history, and train and educate staff.

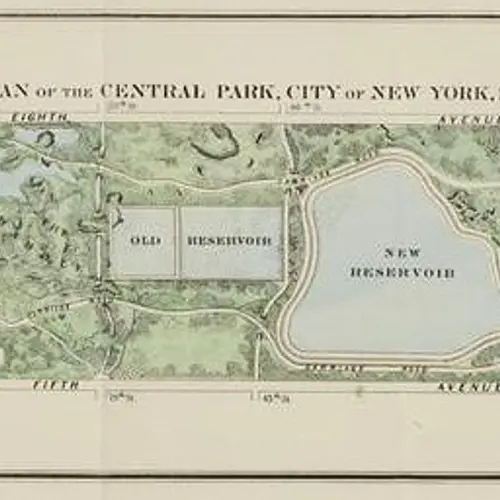

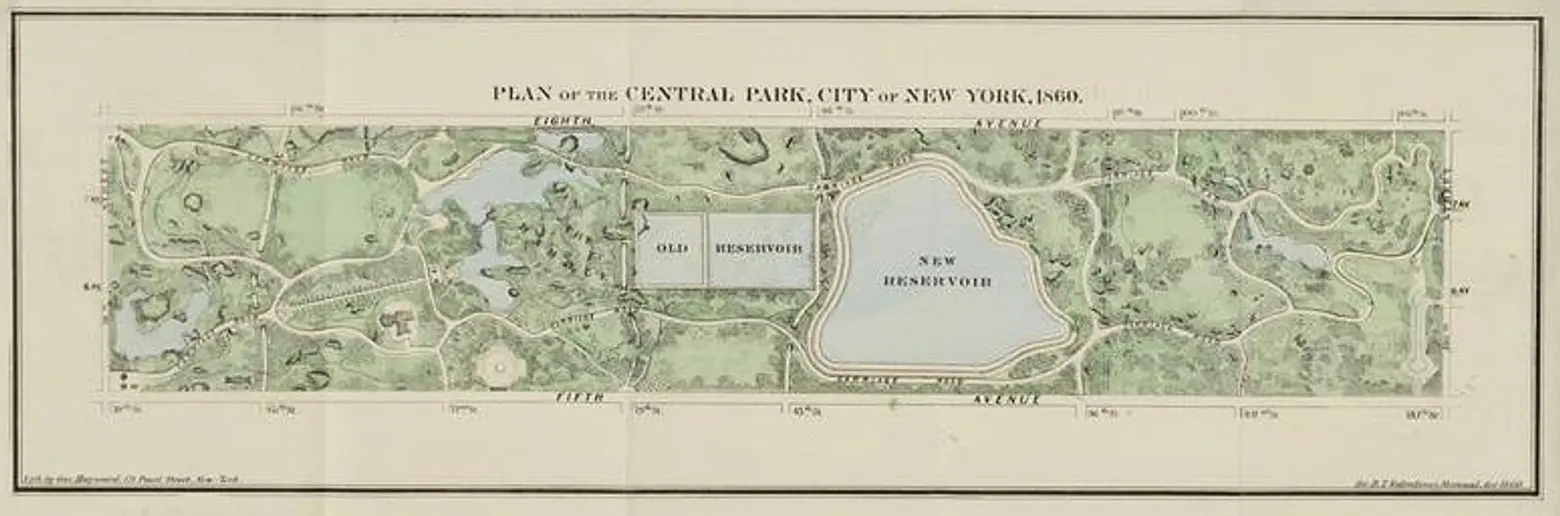

Calvert and Vaux’s plan of Central Park from 1860, courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

Calvert and Vaux’s plan of Central Park from 1860, courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

Going back to the park’s origins, why did the New York State Legislature set aside land for a park?

Sara: Before they set aside land, there was a big movement to have a public park in the city, and it was mainly for two reasons. One was that the business community wanted New York City to be a great metropolis like London and Paris, and they knew that what defined a great city was a park.

On the other side of coin were the social reformers who saw that immigration was coming in the 1840s. There was a tremendous amount of tension, not just in New York, but across American cities. People understood that if you made a great park, it would help people to understand that we are all same. Frederick Law Olmsted, one of the park’s designers, was very worried that people born in the city, rich or poor, would not have contact with nature. There were hardly any parks in the 1811 Commissioner’s Plan because the assumption was that people would gravitate towards the East River or the Hudson River, but the shipping industry took over those areas. Andrew Jackson Downing, who I like to call the Martha Stewart of his day, promoted a park in the 1840s and ’50s, and the movers and shakers of the city got behind it.

In 1851, both mayoral candidates came out in favor of the park. Two years later, after a search for the proper location, this was selected because it was rocky, swampy, cheap land, and it had the reservoirs. Ironically, they said no one would ever want to live near the reservoirs.

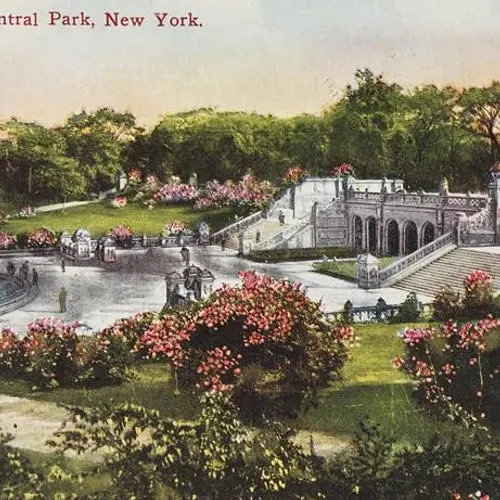

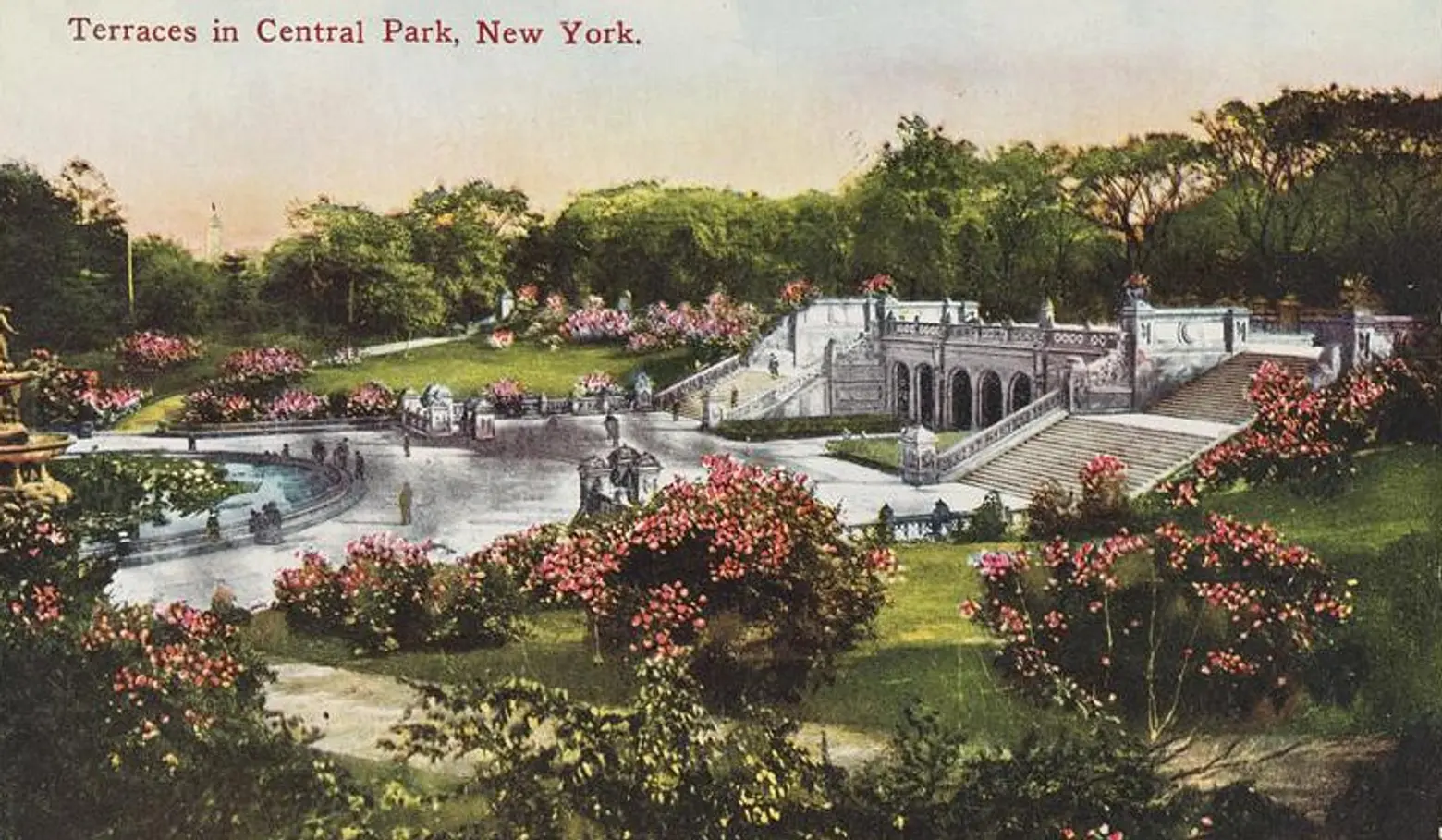

Bethesda Terrace c. 1910, courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

Bethesda Terrace c. 1910, courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

What was it about Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s design that won them the competition?

Sara: Olmsted and Vaux‘s design was incredibly innovative. Every plan had to have eight features, which included transverse roads. Except for Olmsted and Vaux’s entry, the other 32 competitors placed their roads on the service of the park. This meant that traffic would have gone through the park at grade level, not unlike the way it does at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. I like to imagine it was Vaux who thought of sinking the transverse roads underneath the park. Their main goal was to make you forget you were in the city, and traffic would certainly detract from that. They created what would later be called sub-ways, the first use of the term. What that did was bring peace, quiet, and a rural atmosphere to the park.

How did the park end up in a period of decline?

Sara: Even in Olmsted’s time, there were so many political issues about how the park should be managed and what the budget should be. People decided that since the park was still way out of town, there should be local parks. The vicissitudes of politics and the economy really moved how the park was managed. For the most part, it was managed poorly. The park did not have the kind of stability it has had for the past 34 years because of the Conservancy. In fact, this is the longest period of the park’s health, stability, and beauty since its inception.

How did New Yorkers engage with the park when it first opened?

Sara: The park had almost as many visitors then as it did 20 years ago. There were about 12 million visits a year. This was the only game in town. There was no Citi Field or Yankee Stadium. There were no beaches or playgrounds. At the time, City Hall Park was the largest planned park in the city, but everyone who wanted a beautiful experience came to Central Park. It was like the 8th wonder of the world. In terms of an American experiment, people at the time thought rich and poor, black and white, gentile and Jew, wouldn’t get along, but they all came to the park and made peace with each other. It was the first park built by the people, of the people, and for the people. We are really a truly democratic American park.

The Great Lawn today, courtesy of Ed Yourdon via photopin cc

The Great Lawn today, courtesy of Ed Yourdon via photopin cc

Do you think New Yorkers have changed how they engage with the Park?

Sara: They’re definitely more respectful. My favorite turning point for the Conservancy was at the beginning when people were objecting to fences and rules. They hadn’t had rules in 30 years. When we were doing the Great Lawn, we made every effort to inform the public and say, “You have to keep off the grass. The grass has to grow.” About a week before it opened to the public, I was on the lawn taking photos, and I couldn’t tell you how many people yelled at me, “Lady, get off the lawn.” I had to keep saying, “I work for the Conservancy.” Before that, no one would have cared. Now, I see members of the public pick up trash. The public has bought into the fact that if you want to keep it green, you have to pitch in.

Wollman Rink in Central Park, courtesy of Wiki Commons

Wollman Rink in Central Park, courtesy of Wiki Commons

How much of the original design remains?

Sara: I give a rough estimate that one-third of the park is exactly the same, one-third is slightly different, and one-third is entirely different. That entirely different part includes the Great Lawn, which was originally a reservoir. Robert Moses put in 30 perimeter playgrounds. There is a swimming pool and skating rinks. It changed from 28 miles of pathways to 58 miles today. One of the great things the Conservancy has done with cooperation from the Department of Transportation is close several automobile entrances and exits and turn them into land for recreation and pedestrian paths. The woodlands are the hardest to restore, but we do it slowly and very carefully. We always plan for the North, South, East and West so no neighborhood is overlooked.

Pedestrian paths, courtesy of Stuck in Customs via photopin cc

Pedestrian paths, courtesy of Stuck in Customs via photopin cc

What do most people not realize about the park?

Sara: Most people don’t realize that there are three ways to get around the park. The carriage drives are the loop around the perimeter. The bridal paths loop up the west side. The pedestrian paths go everywhere. When Olmsted and Vaux were planning their design, they realized that if the elite didn’t want to mix, they would stay on the carriage or their horse. So, they designed the most beautiful parts of the park for pedestrians only. If you wanted to see these areas, you had to get out of your carriage or off your horse.

Who is the visionary behind the park’s future?

Sara: Douglas Blonsky is a wonderful leader. He started as Construction Manager and worked his way up to President. He is the Olmsted of our day, and like Olmsted who built the park and then managed it, Doug restored the park and now manages it.

What stability has the Conservancy brought to the park?

Sara: What’s important is that we have a wonderful partner, the City of New York, that starting with Mayor Koch, agreed to this public/private partnership. They city recently upped their contribution to the park to 25 percent of its budget. The Conservancy has to raise the other 75 percent of the $57 million budget, which takes a tremendous amount of management. That’s what the Conservancy has brought: planning and management.

The park has gone through so many ups and down over the years, and what the Conservancy has done is plan for its future. Now, there is stability and an endowment for the park. As long as the public supports us, we will have a stable, healthy Central Park.

What does Central Park mean to you?

Sara: I just love this place. It changed my life and gave me a purpose. It’s a place I take my family and feel proud of the work we have done. I grew up in the ’60s and wanted to change the world like everyone did then, and here I wound up changing 843 acres of the world. I was the lucky one chosen to keep the history.

Shakespeare Garden in the fall, courtesy of the Central Park Conservancy

Shakespeare Garden in the fall, courtesy of the Central Park Conservancy

Larry, you oversee Shakespeare Garden. What does that entail?

Larry: It includes researching the plants, ordering them, planting them, and taking care of the plants and grass. It’s taken me three years to put together a plot that I want. If you’re a good gardener, you’re never satisfied with what’s there; you are constantly changing.

Does your work change with the seasons?

Larry: Yes, it does. In the fall we plant bulbs, which are going to bloom in the spring. As the bulbs are blooming, I’m thinking about what works this year and what I want to change for next year. Right now, things like weeds are a big problem; I’m spending a lot of time weeding.

Shakespeare Garden, courtesy of the Central Park Conservancy

Shakespeare Garden, courtesy of the Central Park Conservancy

All of the plants and flowers in the garden are mentioned in works by Shakespeare. How do you choose which to plant?

Larry: Shakespeare mentioned over 180 different plants, grasses, and trees, so there are lots of choices. But if he mentions a lily, I think I can use any lily, which gives a large range of plant material to choose from.

There are a lot of really intelligent gardeners from all over the world who come into Shakespeare Garden. I think visitors from England really get it because the garden is a little messy by American standards. Things flow into each other and sometimes flow into the walkways. It has to be planned chaos. The palette changes because in the early spring most of what we have are daffodils, which are 80 percent yellow. By the time that’s over, we are ready for a change. Other than species tulips, I don’t think I have ever planted a yellow tulip. Now we are in a blue and purple period.

Are there some little-known but famous facts about the garden?

Larry: One of the benches is dedicated to Richard Burton. Sometimes I think about placing an Elizabeth Taylor rose right next to it. There are ten plaques with quotes from Shakespeare, and the plants around them are mentioned on the plaques. The Whisper Bench is one of the benches here. If someone whispers on one side, the person on the other side can hear it.

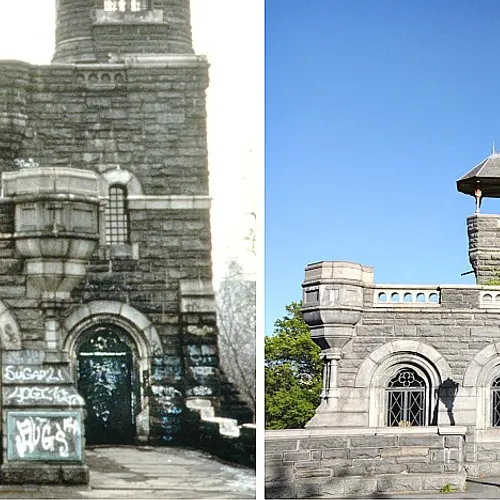

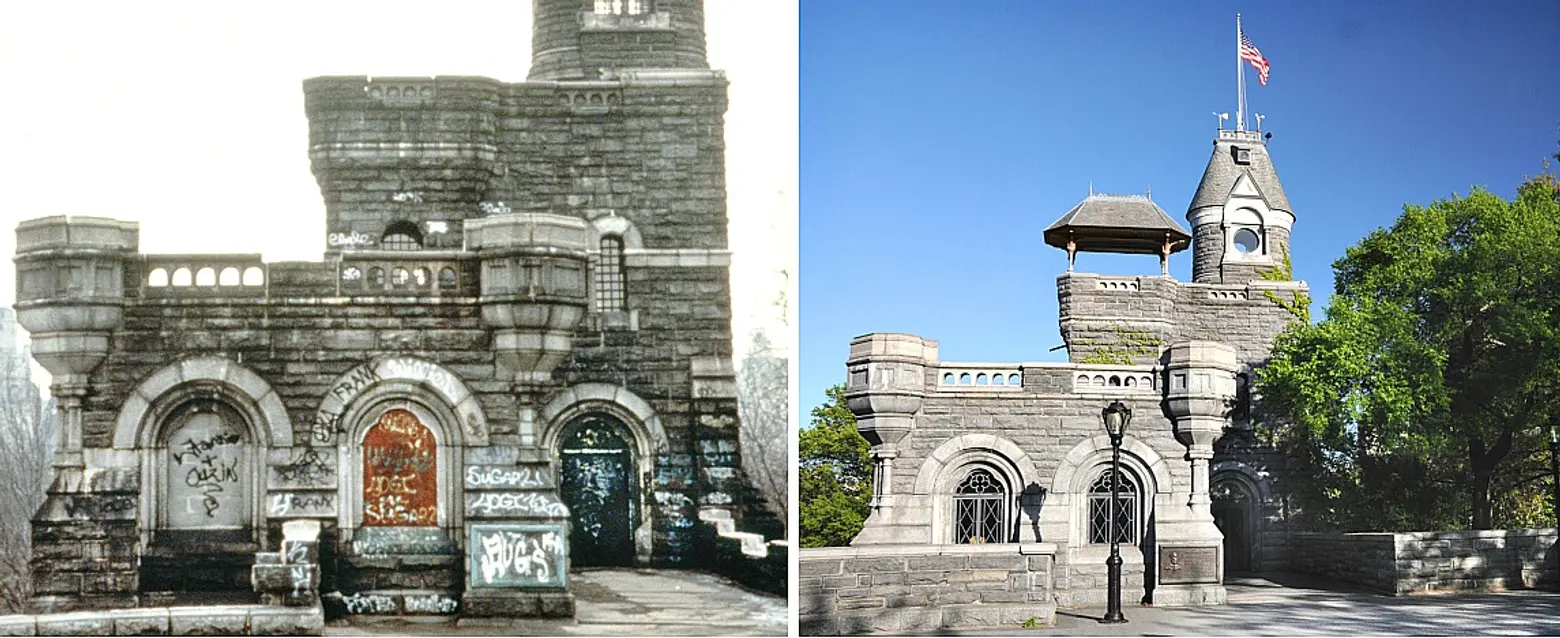

Belvedere Castle before and after the Conservancy’s restoration, courtesy of Central Park Conservancy

Belvedere Castle before and after the Conservancy’s restoration, courtesy of Central Park Conservancy

What makes the garden unique within Central Park?

Larry: First of all, it’s sort of hidden. It’s also very windy. It makes people slow down and look around.

Yesterday we had six weddings going on. People get married up at Belvedere Castle near the Whisper Bench, by the sun dial, and right at the entrance to the garden. Then they come back for their anniversaries. A really touching thing happened a year ago. A very quiet gentleman was sitting on a bench, and he said to me, “Thank you for keeping up the garden.” His wife had died, and they had gotten married in the garden. It makes you realize how special it is.

What is the history of the garden?

Larry: This garden has been here since 1912. It was developed for a nature study by the Parks Department entomologist at the request of Commissioner George Clausen.

Sara: When Mayor William J. Gaynor died in 1913, Parks Commissioner Charles B. Stover, the Mayor’s best friend, changed the name to Shakespeare Garden officially to reflect the Mayor’s favorite poet.

Larry: When the Conservancy began in 1980, one of the organization’s first projects was to redo the garden. The Rudin family paid for the restoration in 1988. The Mary Griggs Burke Foundation and the Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation have endowed the garden. I have a lot of people who say, “I joined the Conservancy because of the garden.”

Shakespeare Garden before and after the Conservancy’s restoration, courtesy of Central Park Conservancy

Shakespeare Garden before and after the Conservancy’s restoration, courtesy of Central Park Conservancy

Where does the Conservancy fit in with taking care of the garden?

Larry: If the Conservancy weren’t here, it would be rundown again and taken over by invasive plants. Plus, there would be no one to pick up the trash. Unfortunately, our visitors leave a lot of trash.

What do you enjoy about working for the Central Park Conservancy?

Larry: Zone Gardeners are in charge of a zone. You take pride in your own little space. This four acres is sort of “my” garden. This is one of the great jobs in the Conservancy, I think. I have a lot of freedom. I submit what I want for approval, and it’s really a privilege to see the garden every day and how much it changes. And you can only experience that if you see it everyday.

***

[This interview has been edited]

Lead image courtesy of Lorenzoclick via photopin cc