‘No end in sight’: How NYC is dealing with the growing hunger crisis

City Harvest driver Ramon Vargas, July 17, 2020, in New York. Photo by Jason DeCrow for City Harvest

While the spread of the coronavirus in New York is waning, another crisis shows no signs of slowing. The number of people experiencing food insecurity in New York City continues to grow, with a projected increase of 38 percent this year compared to 2018. In response, nonprofits like City Harvest, the city’s largest food rescue organization, have tremendously scaled up their operations to meet demand. The group has rescued more than 42 million pounds of food since March, a 92 percent increase from the same period last year.

With the extra unemployment benefits expected to run out or be cut by the end of the week as part of the next congressional COVID-19 relief package, the number of hungry New Yorkers, more than 1.4 million people before the pandemic, could double. City Harvest, which had to get creative after 96 of their agency partners closed early on in the crisis, will continue to do what they do best: get food in the hands of those who need it.

Josh Morden, who is the senior manager of supply chain planning at City Harvest, said the organization previously had to adapt its response in times of crisis, like during Hurricane Sandy or the Great Recession in 2008 but never has the need been so great as it is currently. “Nothing where we’ve seen the need to scale up so drastically,” Morden told 6sqft in an interview. “And it looks like there will be no end in sight at this point.”

When the crisis first hit New York City, which quickly became the epicenter of the outbreak in the United States, City Harvest had to adapt their operations to get more food out as fast as possible. In the beginning, 96 of their partner agencies–constituting about a third of their network–halted operations because of the pandemic. The organization worked with food distribution partners, onboarded 31 sites, and continued to get food out. Since the COVID-19 response began in March, City Harvest has distributed roughly 35 million pounds of food.

On top of the health emergency, the economic impact of the pandemic is enormous. New York City’s unemployment rate has jumped to roughly 20 percent in June, compared to 4 percent last June. Crowds now lining up at food banks and visiting places like City Harvest’s Mobile Markets appear younger than those who previously visited, in need of assistance themselves or helping their vulnerable neighbors.

“We’re seeing people who have never needed food assistance before turning to soup kitchens and food pantries to feed themselves and their families,” Morden said.

There’s more than just anecdotal evidence of increased demand for food assistance. In April, during the peak of the virus in New York, the number of recipients of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) increased by 68,714, the largest one-month actual increase in food aid recipients for the city in modern times, according to Hunger Free America.

And new user registrations on the mobile app Plentiful, which connects New Yorkers to nearby food pantries and allows them to make reservations in advance, are soaring. Since March, there have been 139,063 new unique users, compared to 51,300 during the same time last year, according to data provided to 6sqft. In a recent survey of 20,000 new SMS registrants since April 3, roughly 83 percent said they had not visited a pantry in the last six months.

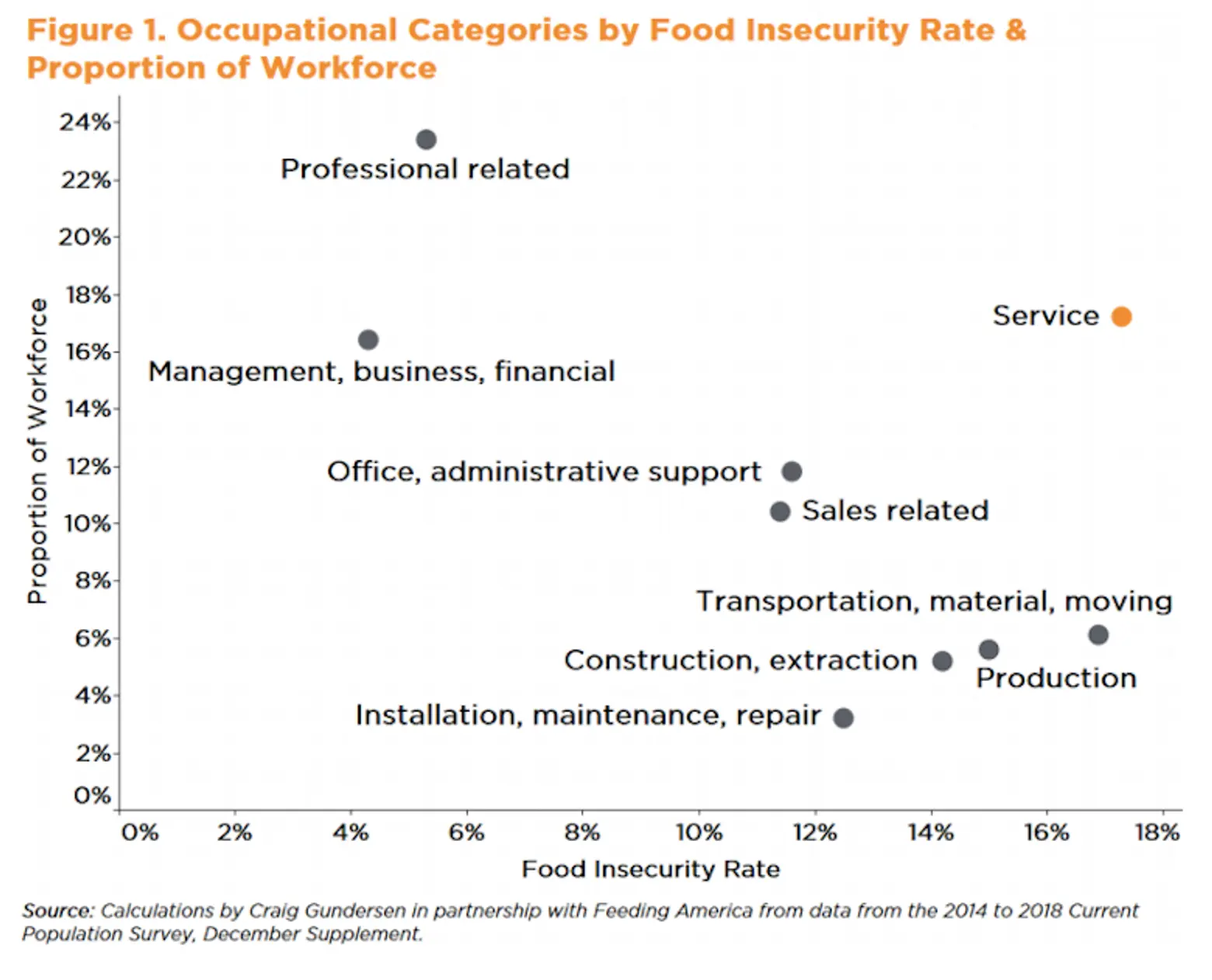

Chart courtesy of Feeding America

In the NYC neighborhoods that have been hardest hit by the virus, largely in minority and low-income communities, hunger is now an urgent concern. According to Feeding America, individuals who experience food insecurity are more likely to have poorer health, making them more vulnerable to severe illness from COVID-19.

The organization also found that workers with service or hospitality jobs are more likely to be food insecure due to lost wages from pandemic-related shutdowns. As a May report by the Center for an Urban Future found, a majority of workers in these hard-hit sectors live in low-income neighborhoods.

While every borough in the city is projected to see an increase in overall food insecurity this year, the Bronx and Brooklyn will see the largest percentage of food insecure New Yorkers in the state. According to Feeding America, food insecurity in the Bronx will increase from 17.5 percent in 2018 to 22.7 percent this year, with Kings County seeing an increase from 14.3 percent in 2018 to 19.1 percent in 2020.

Coupled with the closure of schools and loss of income for parents because of the virus, the situation for New York City children is dire, with hunger rates among children growing by nearly 50 percent since March. According to an April report from Hunger Free America, nearly four in ten parents in the city are cutting the size of meals or skipping meals for their children because they did not have enough money for food.

Since the start of the lockdown in mid-March, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has worked to meet demand by ramping up its existing food delivery systems and investing in the city’s emergency food reserve as part of the $170 million “Feeding New York” plan.

“Whoever you are, wherever you are, if you need food, we’re here for you, and there should be no shame,” de Blasio said during a press briefing in April. “I want to emphasize this. There’s no one’s fault that we’re dealing with this horrible crisis.”

The city has been delivering meals during the crisis to those who cannot access any food themselves, with help from Taxi and Limousine Commission-licensed drivers. The city’s Department of Education also set up over 450 grab-and-go “Meal Hubs” to provide all New Yorkers with free daily meals. Since March, the city has distributed 100 million meals to New Yorkers in need because of these programs, de Blasio announced this month.

In May, the state was approved to distribute the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer, or P-EBT, a federally-funded program that will provide every public school student in the city $420 for groceries, regardless of income and immigration status. Parents who already receive SNAP or Medicaid started receiving the benefits in June, with others expected to receive the money in the coming weeks.

Over two months ago, the House of Representatives passed the HEROES Act, which, in addition to extending the extra employment benefits provided as part of the CARES Act from March, increases SNAP benefits by 15 percent, extends the length of time that the P-EBT program stays in effect, and provide assistance to food distribution organizations.

But the next federal stimulus package has not moved forward after Senate Republicans presented their own bill this week that calls for the extra unemployment benefits to be reduced from $600 per week to $200 per week. The bill presented by the GOP does not include the extra SNAP benefits but does have another round of one-time $1,200 payments for some Americans.

Without an increase in SNAP and federal unemployment benefits, the need for food assistance will grow in New York. If the HEROES Act or something similar does not get passed, City Harvest and other organizations will continue to do what needs to be done in order to get as much additional food to New Yorkers in need as possible.

“SNAP goes a long way towards alleviating hunger but doesn’t eliminate it because the benefits aren’t high enough,” Dottie Rosenbaum of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, told the New York Times. “Omitting a boost in SNAP benefits would be an unconscionable failure.”

Food insecurity is experienced by a wide variety of people; about one of every eight Americans now receive SNAP benefits, the Times reported. And hunger in New York isn’t just felt by those with the lowest-incomes, Morden said, but also by working-class families.

“It’s not an issue that is necessarily being experienced solely by the homeless population,” Morden said. “A lot of people who visit our Mobile Markets or who visit our partner agencies and soup kitchens, they have jobs, they have employment. But New York City is a very expensive place to live and sometimes you’re forced to choose between paying your rent and buying groceries.”

+++

Learn where to find free food, how to get meals delivered, and how to apply to food assistance programs, as well as how to help your vulnerable neighbors here. Resources related to free food assistance programs offered by the city can be found here.

RELATED:

- A guide to food pantries and meal assistance in NYC

- NYC releases $170M plan to feed New Yorkers throughout coronavirus crisis

Editor’s note 7/30/20: This post originally stated City Harvest distributed 35 million pounds of food between March and July 2020. The group rescued 42 million pounds of food during that time.