Looking back at the Depression-era shanty towns in New York City parks

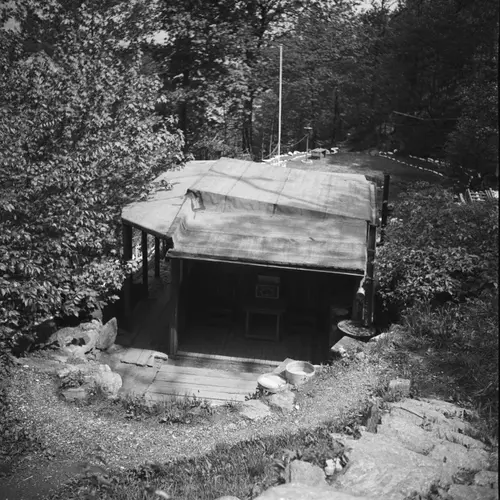

Squatters Colony, Red Hook Recreation Area, September 12, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

Today, New York City’s rising cost of living has made affordable housing one of the most pressing issues of our time. But long before our current housing crisis–and even before the advent of “affordable housing” itself–Depression-era New Yorkers created not only their own homes, but also their own functioning communities, on the city’s parkland. From Central Park to City Island, Redhook to Riverside Park, these tent cities, hard-luck towns, Hoovervilles, and boxcar colonies proliferated throughout New York. Ahead, see some amazing archival photos of these communities and learn the human side of their existence.

Squatters at Riverside Drive and 90th Street, August 16, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

Following the Crash of ’29, millions of Americans lost their jobs and their homes as the economy plummeted. In New York, unemployed men could sleep at the city’s Municipal Lodging Houses, which served about 10,000 people a day, or at various Salvation Army lodges in exchange for a sermon; or, they could lie on the floor of the rotgut liquor joints on the Bowery. Options were thin, and by the winter of 1931-32, 1.2 Million Americans were homeless, and 2,000 New Yorkers were living on the street, according to the New York Times.

Scores of New Yorkers made homeless by the Depression began to build their own makeshift homes on the city’s parkland. Across the country, such settlements were known as Hoovervilles, named for Herbert Hoover who had presided over the Crash and the early years of the Depression yet did very little to alleviate the nation’s suffering.

Inwood Hill Park, Squatters, February 9, 1934, courtesy of NYC Parks

The most famous Hooverville in New York was Hoover Valley, which sprung up in Central Park on what is now the Great Lawn. The Lawn had once been a reservoir, and a major part of the city’s Croton water supply system. That reservoir was drained in early 1930 to make way for the Great Lawn, but the Depression slowed the changeover, so that by the end of that year, the area was an expanse of dirt where a small group of men had begun to live until they were evicted by the police.

A year later, as public sentiment turned in sympathy with the struggling poor, newly built “shacks” began to appear on the reservoir site. The men turned to the park not only for the open space it provided but also for the potential food it offered: Questioned as to why he was shaking one of the Park’s mulberry trees in the summer of 1933, a Hoover Valley resident explained, “We do this every day. We eat the berries. You know in the bible people lived off fig trees, so we live off these mulberry trees here in the park.”

Though Hooverville residents built their homes with found objects like salvaged wood or packing crates, each dwelling reflected the pride and ingenuity of the people who built them. For example, in 1932, the 17 shacks along Hoover Valley’s “Depression Street” all sported chairs and beds, and a few even had carpets. One particularly notable dwelling was built out of brick. As the Times notes, the structure was constructed by unemployed bricklayers who called their creation “Rockside Inn” and outfitted it with a roof of inlaid tile.

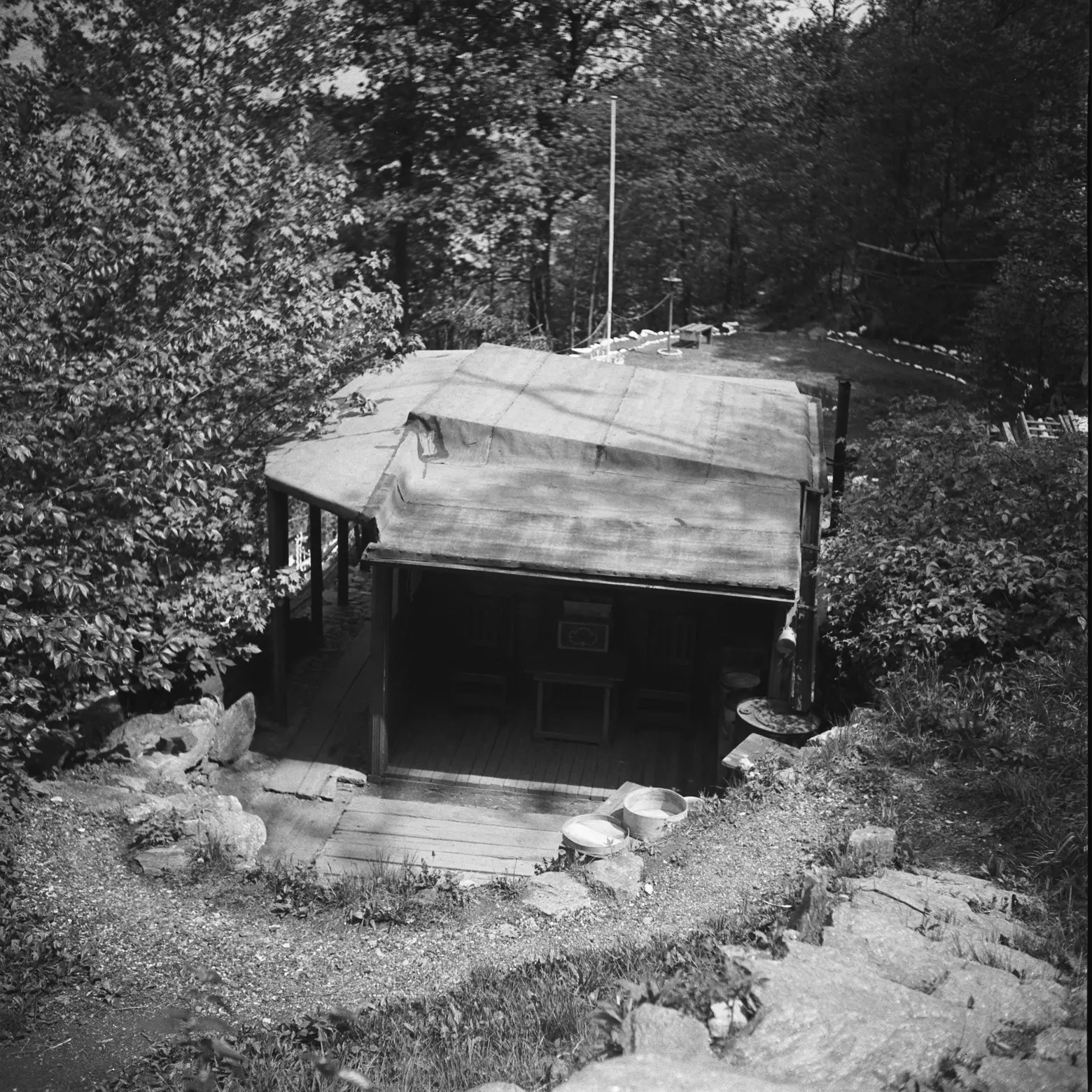

Fort Washington Park, Squatters at Home, 190th Street, May 18th, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

Fort Washington Park, 190th St, Squatter’s Home, May 18, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

Most of the men who lived in Hoovervilles across the city and the country were not accustomed to homelessness or even, in many cases, to poverty. Consider John Palmerini, who lived in a shack near the Hudson River north of 96th street. The Times reported that “he had served with the Italian Army, and had been a chef at the Café Moulin Rouge in Paris and at the Hotel de Mayo in Buenos Aires, and had lost his savings in a restaurant in Poughkeepsie, [but] is still looking for work and is confident of eventual success.”

Indeed, Hooverville residents “do no panhandling,” the Times explained in 1933. They did not beg. They worked whenever they could. Jobs included polishing automobiles or salvaging newspaper. The Depression had reversed fortunes in extraordinary dramatic ways, but in spite of their new circumstances, citizens of Hooverville endeavored to live with dignity. One resident of Central Park’s Hoover Valley explained, “We work hard to keep it clean, because that is important. I never lived like this before.”

Riverside Park, 100th St at Hudson River, Squatter’s Shack, April 26, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

That pride of place was common among all the shanty-towns that sprang up in New York. “Camp Thomas Paine,” was a 52-shack “Tin City” in Riverside Park at 74th Street, which was home to 87 WWI Veterans. There, the residents had chosen a leader, Commander Clark, shared rotating guard duty, and established both a “mess hall” and a “clubroom” with an open fireplace, where men could sit, read, smoke, chat, and play checkers. By the fall of 1933, they even had a stove to roast Thanksgiving turkey. But the most striking element of this settlement might have been the pets kept in a corral that included turkeys, ducks, rabbits, and chickens. “Nothing that enters this camp alive will ever be killed,” Clark explained.

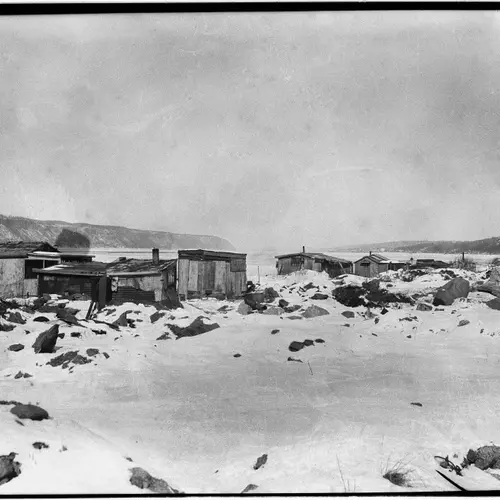

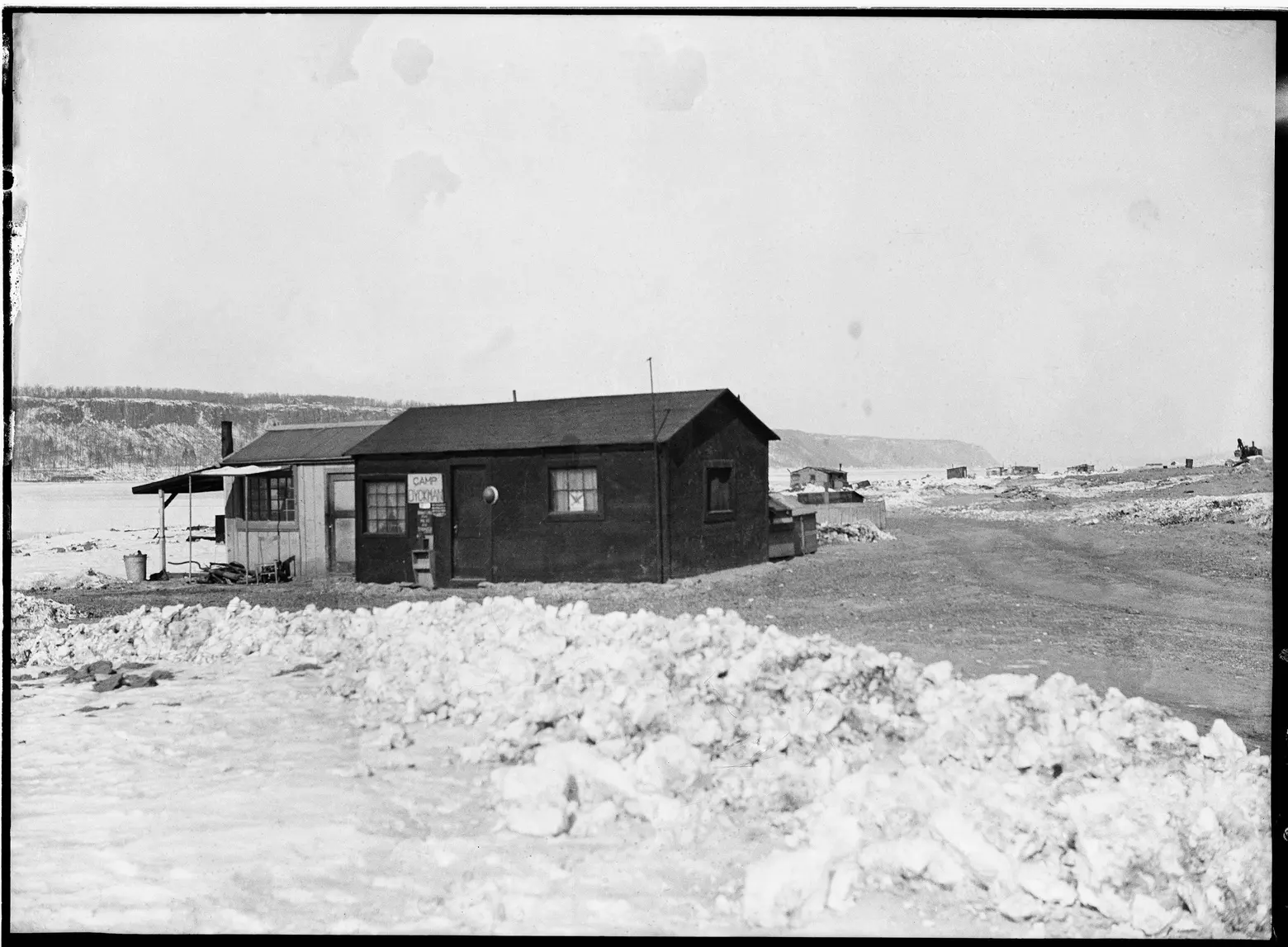

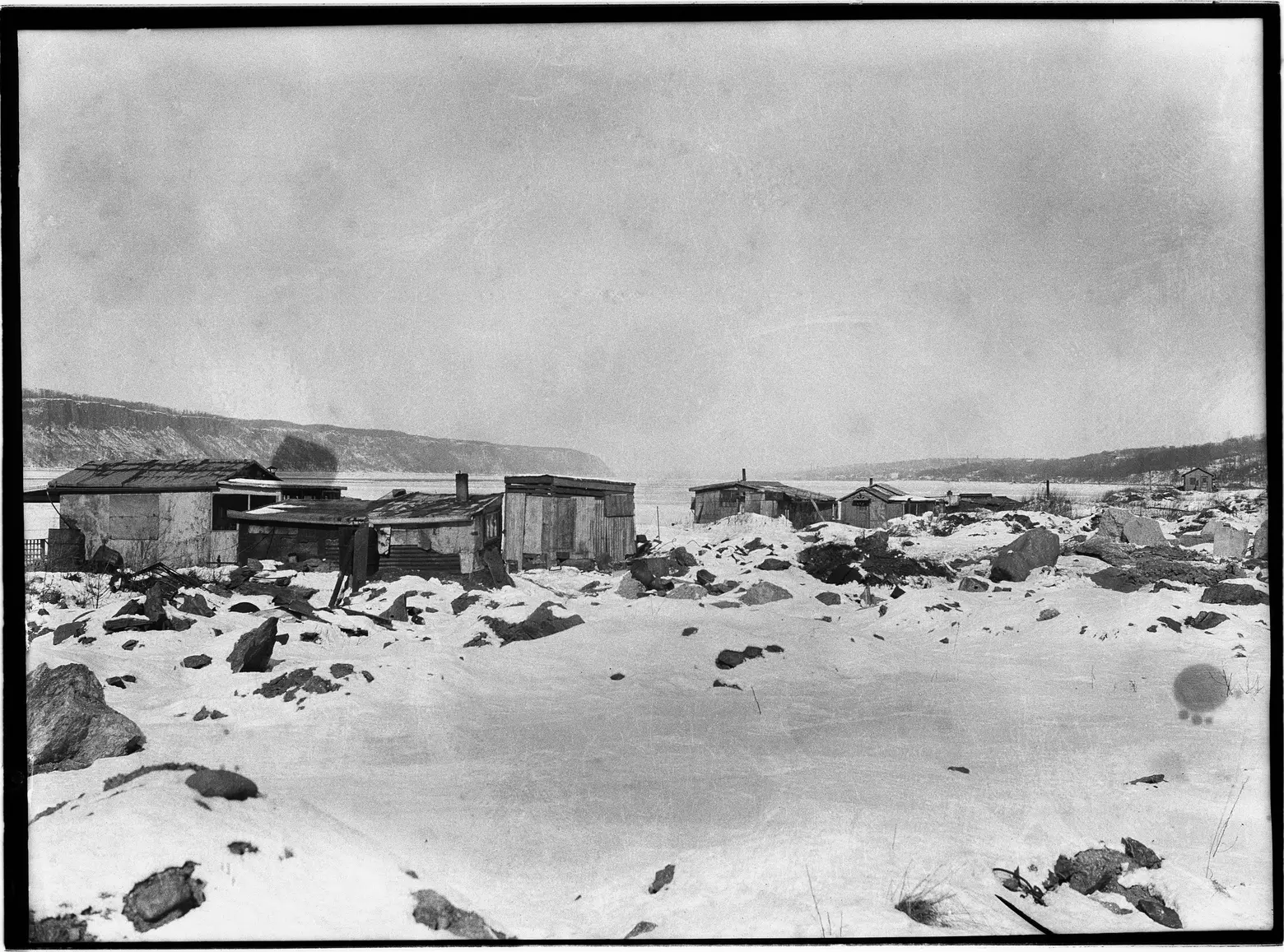

Red Hook Recreation Area, Squatters’ Colony, end of Hicks St Basin, site of Playground, September 12, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

That care was also evident in Red Hook’s Tin City. The City stood on what is now the Redhook Park and Recreation Center. Before it became a park, it was an empty lot along the waters’ edge that served as a dumping ground for industrial debris. Unemployed Merchant Seamen who wanted to stay near the docks should work become available fashioned that debris into homes. By the winter of 1932, there were more than 200 makeshift homes in the Redhook Hooverville. This settlement was somewhat unique amongst Hoovervilles because it did not cater exclusively to men. There were women and families there, and babies were even born in the settlement.

Red Hook Recreation Area, Squatters’ Colony, view East, site of Playground, September 12, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

With not much more than newspaper to insulate their dwellings from the fierce winds off the harbor, citizens of the settlement gritted their teeth against what the Brooklyn Eagle called “the dreariest winter.” But even in the face of sharp gales and sharper hunger, members of the Redhook Hooverville created streets and lanes within their “city” and even endeavored to make yards around their homes. They’d double and triple and quadruple up against the cold, with as many as 11 people living together in a single structure, making $8 last a week between them.

Red Hook Recreation Area, Squatters’ Colony, view Southwest, site of Playground, September 12, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

The “mayor” of Red Hook’s Hooverville was Erling Olsen, an out-of-work Norwegian seaman and amateur evangelist who came to New York in 1904, and “founded” the Tin City when he made “shack 77” his home in 1928. He transformed another one of the shacks into the “Beth El Norwegian Mission” and held Sunday services. When he died, after being struck by a hit-and-run driver in November 1933, the Times reported, “a tattered American flag flew at half-staff over Olsen’s shack.”

Olsen’s counterpart at the East Village Hooverville known as “Hard Luck Town” was Bill Smith, unofficial mayor. Hard Luck Town was the city’s largest Hooverville, according to Off the Grid. It stretched between 8th and 10th streets on the East River. Smith had laid out the first shack there in 1932, made out of packing crates and shipyard scraps. Within months, there were 60 more shacks, organized along Jimmy Walker Avenue and Roosevelt Lane. Soon Hard Luck Town was home to 450 men who took it upon themselves to create a “City Hall” (Smith’s shack), and a variety of municipal services for the shanty-town including a street cleaning department.

Fort Washington Park, 190th St, Squatter’s Home, May 18, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

Every one of these Hoovervilles was demolished by Robert Moses. Hoover Valley in Central Park was the first to go. It was swept away by April 1933, when work on the Great Lawn resumed. Hard Luck Town was cleared with just 10 days’ notice the same year. Hard Luck resident “old John Cahill” remarked upon the loneliness of the situation. He told a reporter, “Nobody’s askin’ us where we’re goin’. There’s not a soul thinkin’ about us.”

Riverside Park, Squatter’s Shack, April 26, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

But many people were, and when Camp Thomas Paine was slated for demolition on May 1, 1934, even the untouchable Moses caught some flack for the situation. Park Avenue resident Louis P. Davidson tried to have the eviction postponed and to find other municipal land for the colony. But Moses’ office stood firm that no other parkland could be made available.

The Board of Alderman itself voted unanimously to censure Moses over his handling of Camp Thomas Paine. On April 30th, 1934, a day before the official eviction date, they passed a resolution demanding that the order be rescinded and accused Moses of “steam shovel government.” Moses scoffed, calling the vote “just cheap politics.” What did people matter when construction was at stake? “How can we progress on the West Side Improvement without removing all encroachment along the river? I don’t take their action seriously,” he said. Indeed, by the end of the year, Parks reported, “This colony has been removed, shacks burnt down, site graded, and plans are now underway for the West Side Improvement.”

Inwood Hill Park, Squatters, February 9, 1934, Courtesy of NYC Parks

Instead of burning Red Hook’s Tin City to the ground, Moses paid residents to tear it down. In its place, he built Red Hook Pool and Recreation Center, which opened to much fanfare during the 1936 Summer of Pools.

By Thanksgiving of 1934, there was one Hooverville left in New York. Why was it still there? It wasn’t on Parks Department land. It stood on West Houston Street between Mercer and Wooster on land owned by the Board of Transportation, which was earmarked for the IND subway.

Red Hook Recreation Area, Squatters’ Colony, view East, site of Playground, September 12, 1934

As the Depression wore on, many Hooverville residents would take jobs in the various government relief programs like the WPA and the CCC. Their New Deal labor helped build the city and its parks that we know today.

RELATED: