Behind the scenes at Little Italy’s Elizabeth Street Garden and Gallery

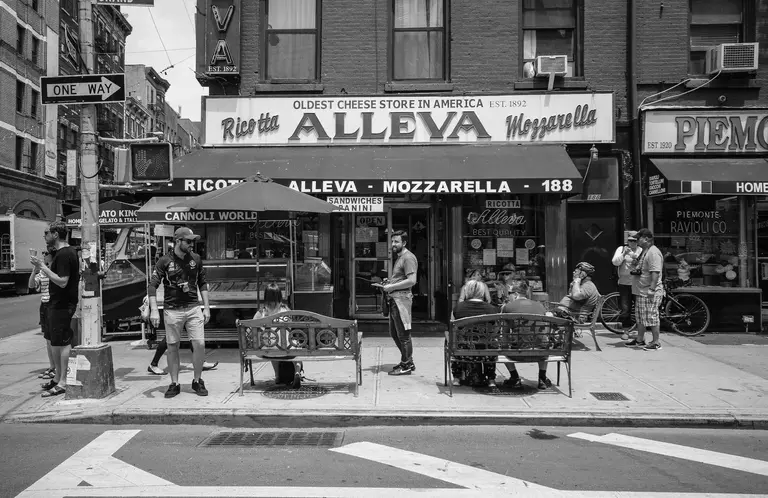

The gallery is housed in a 19th-century firehouse, and later bakery, on Elizabeth Street. It has its own door to the garden next door

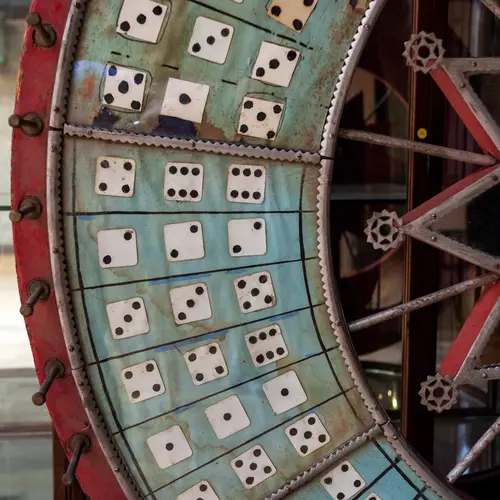

Shortly upon arriving in New York in the 1990s, Allan Reiver traveled to Coney Island with one goal in mind: find a shooting gallery. Reiver, who has always had a knack for finding art out of other people’s junk, bought one that same day from an older man who told him it had been boarded up since the 1930s when it became illegal to shoot live ammunition. Nearly 30 years later, the 10-foot high boardwalk game, still operational, sits in the back of the Elizabeth Street Gallery in Little Italy, where Reiver has housed unique artifacts and fine objects for nearly a decade.

Rare finds can also be found next to the gallery, scattered across a lush green space known as the Elizabeth Street Garden. Since 1991, Reiver has leased the land from the city, slowly transforming the lot with unique sculptures, columns, and benches, all plucked from estate sales. In 2012, the city revealed plans to replace the garden with a senior affordable housing complex, known as Haven Green, igniting a battle between garden advocates and affordable housing supporters. The City Council votes on the project Wednesday. Ahead of the decision, 6sqft toured Reiver’s gallery and the garden next door and spoke to him about building the green space and the plan to fight the Haven Green project in court.

Reiver found this still-operational shooting gallery on Stillwell Avenue in Coney Island in 1991. Manufactured by the Mangels Company, the gallery contains 90 percent of its original paintwork.

“I moved here in 1990, which is really when my life started over,” Reiver said. That year, the former developer moved to Elizabeth Street and began renovating an old loft. He has never lived on another block since. According to Reiver, this strip of Little Italy, between Spring and Prince Streets, was nearly entirely industrial during that time.

“There were no restaurants, no retail stores, no nothing,” he said. When he first moved to the block, Reiver lived in a $1,000/month 5,000-square-foot loft, across from where his gallery is now located. He had direct views overlooking the vacant lot, which had no grass and was full of trash.

When the city announced plans to develop a parking lot on the space, community members asked Reiver to lease the lot from the city and turn it into a garden. At that same time, mansions of Long Island and New Jersey were being subdivided and abandoned, items of the home’s gardens out on the curb.

“It was totally fortuitous,” he told us. “It was a vacant lot and at the time they were tearing down gardens. It all fell into place for me and that’s why it’s here.”

After acquiring the $4,000 per month lease in 1991, Reiver said his first idea was to not only plant grass and trees but to connect three blocks– Elizabeth, Mott, and Mulberry– via a gravel pathway. “My first inclination was to build a walkway from Elizabeth Street to Mott so it would connect two neighborhoods.”

But as a life-long collector of interesting objects, he also started filling the space with items found from the gardens of abandoned estates in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and on Long Island. “I’ve collected all my life stuff that people were throwing away.”

The first items placed in the garden include this gazebo and two columns near the gallery side of the garden, all found at a Pennsylvania estate state.

The big red stones near the entrance way, which Reiver describes as having a “real primitive” look to them, were placed there early on. They weigh so much they’ve sunk at least six inches in the ground.

“There was no real plan,” Revier said, about the park’s design. “When I got things I would just pick a spot and put it there.”

The first items planted in the garden included a gazebo and two columns, both of which came from a home overlooking the Hudson River. Without knowing who had built it at the time, Reiver took the gazebo apart bolt by bolt and had a tow truck lift the columns onto a truck to bring them to the garden. He later found out that Frederick Olmsted, the landscape architect behind Central Park and Prospect Park, designed the park where the gazebo was found. This was the one object that Reiver had chosen a permanent spot for immediately.

With no background in landscape design, he didn’t exactly have a plan for the garden.“When I got things, I would just pick a spot and put it there. If it didn’t look good, I would move it. Some things got moved three or four times before they got a final site.”

The balustrade found in the center of the garden uniquely defines the space

The next major piece he picked up came from Lynnewood Hall, the 34-acre estate of Peter Widener outside of Philadelphia. Reiver scooped up about 100 feet of 20th-century balustrade from the mansion’s garden, which now clearly defines the garden’s paths.

When his collection grew too big, Reiver purchased the building at 209 Elizabeth Street to house the items. Located within a late 19th-century firehouse and former bakery, Reiver’s gallery features items picked up over the last 50 years of traveling the country and the world, from stone lions carved in Italy to foundry pattern mirrors.

Reiver has gifted items from the gallery to the garden next door; these, however, are not for sale. When the gallery opened in 2005, the garden became accessible to the public, although only by walking through Reiver’s building.

As part of the 2012 Essex Crossing development deal, Council Member Margaret Chin asked former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration to build housing for seniors on the site of the garden. But according to Reiver, no one from Manhattan’s Community Board 2 knew of the deal until a year later.

“Nobody in CB2 was even aware of this,” he said. “No one even in the community knew this.”

Soon after, members of the community board came to Reiver and asked him to fully open the garden to the public. Prior to 2013, the only way to visit the garden was by walking through his gallery. “The only thing to do was to open it to the public,” Reiver said. “Let the public defend it. Let the public fall in love with it.”

Kids love the park, Reiver told us. “They come in here and see things they’ve never seen before, like the lion.”

A sign asking for donations to the Elizabeth Street Garden’s defense fund sits at the entrance to the garden

Local residents and businesses formed the Friends of Elizabeth Street Garden nonprofit to fight the city’s plan to raze the garden, as well as oversee its upkeep and plan community programs. The group splintered and a new nonprofit, the Elizabeth Street Garden Inc. (ESG), was formed in 2016.

The group, run by Reiver’s son Joseph, filed a lawsuit against the city in March, which will be heard once the city makes a final determination about the project. The lawsuit claims the city did not properly evaluate the environmental impact of razing the garden. While Reiver holds the lease to the property, ESG operates independently from him.

“We’re hoping that someone on City Council stands up and says wait, this is wrong,” Reiver said. “We’re the most underserved part of the city in terms of green space. This thing is used by more than 100,000 people a year. What are you doing?”

Developed by Pennrose Properties, Habitat for Humanity, and RiseBoro Community Partnerships, the seven-story development Haven Green is expected to bring 123 affordable units for seniors earning between $20,040 and $40,080 annually, as well as formerly homeless seniors.

The project does include a public green space, but it measures just over 7,600 square feet compared to the current site’s 20,000-square-foot space, and a new headquarters for Habitat for Humanity NYC. The building will be built to passive house standards, designed to reduce carbon emissions.

In a 2016 Gotham Gazette op-ed, Chin wrote that pursuing a 100 percent affordable housing building was not an easy decision. “But in my heart, I know this is the correct decision,” Chin wrote. “Because for me, leadership isn’t about always doing what is popular, but what is right.”

Reiver and the garden have repeatedly pushed back at the idea that open space must be sacrificed for affordable housing by suggesting alternative sites for the Haven Green project. Specifically, the group and the community board have recommended a city-owned lot just blocks away at 388 Hudson Street. There, according to the community board, a building could be built with roughly 600 units of affordable housing.

“She’s giving them crumbs,” Reiver said, referring to Chin. “If I was someone who really needed affordable housing, I’d be much more in favor of a 600-unit project than 120. The odds of being accepted are five times greater. She’s really diminishing the odds of people being able to get housing.”

But Haven Green developers say the designated site at 21 Spring Street is the only developable site controlled by the city’s housing agency. The site at 388 Hudson is managed by the environmental protection department and contains a water system access shift, preventing any viable development there.

The developers also argue that the neighborhood, which has a median home value of $2 million and a population more than 75 percent white, has not done its fair share in lessening the affordability crisis in the city. Notably, the area of CB2 has seen the construction of just 93 new affordable units since 2014; in Brooklyn’s East New York, seven blocks gained 648 new units over the same time frame.

Plus, the city simply does not have enough affordable senior housing to meet demand, as City Limits reported earlier this year. A policy organization called LiveOnNY estimated that the waiting list for an affordable apartment citywide consists of about 200,000 seniors.

“There’s no other space down here like it,” Reiver said. “This is natural and very purpose-free, which makes it seem like it’s not forced.”

The project got approval from Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer in February, followed by the City Planning Commission.

“In a neighborhood that has so few undeveloped parcels, every piece of vacant land has the potential to meet multiple and at times competing neighborhood needs,” Commissioner Marisa Lago said during the April hearing. “And in a neighborhood with an area median income as high as this one, the search for land on which to construct affordable housing is especially challenging.”

The City Council is expected to approve the Haven Green project on Wednesday, as members rarely reject an initiative supported by the local representative, in this case, Council Member Chin.

“I think unfortunately tradition will outweigh reason,” Reiver said of the Council’s vote. “I think even a guy like Corey Johnson, who I really consider brilliant, is going to bow to tradition.”

On a sunny, cloudless day in June, Reiver proudly pointed out all of the different sculptures, statues, and other unique pieces he’s picked up and placed in the garden. When asked if there’s something he’s most proud of in the garden, Reiver replied: “The people that are here. The fact that people come in here every day and enjoy it and love it.”

“I built this 30 years ago,” he said. “This is my life. This is my soul. This was supposed to be my legacy to the city. I’ll be 77 years old in six months. I’m not going to live much longer. This is what I planned to leave behind.”

RELATED:

- Senior housing complex at Elizabeth Street Garden site gets borough president approval

- To save Nolita’s Elizabeth Street Garden, a nonprofit wants to take ownership from the city

- City will replace Nolita’s Elizabeth Street Garden with 121 affordable apartments for seniors

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft