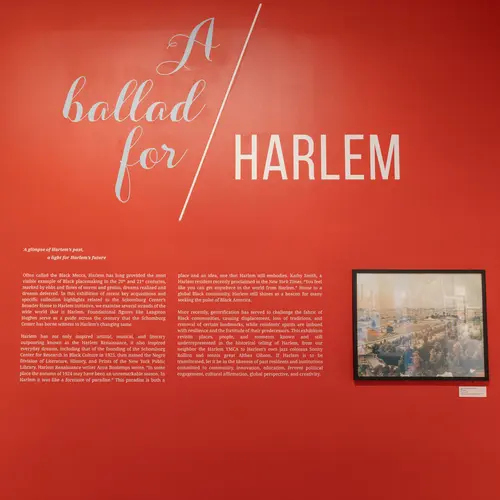

New Schomburg Center exhibit explores 20th-century Black placemaking in Harlem

“Harlem Street Scene Showing Local Businesses,” 1939, Photographer: Sid Grossman, Street Scenes Collection, Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

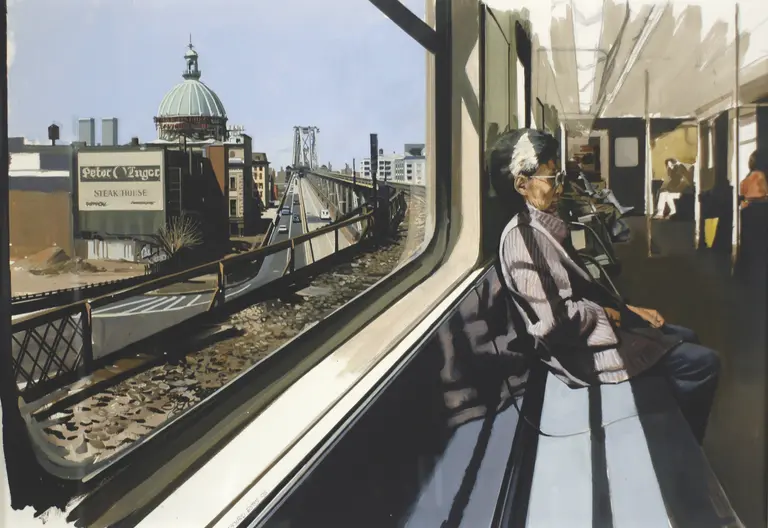

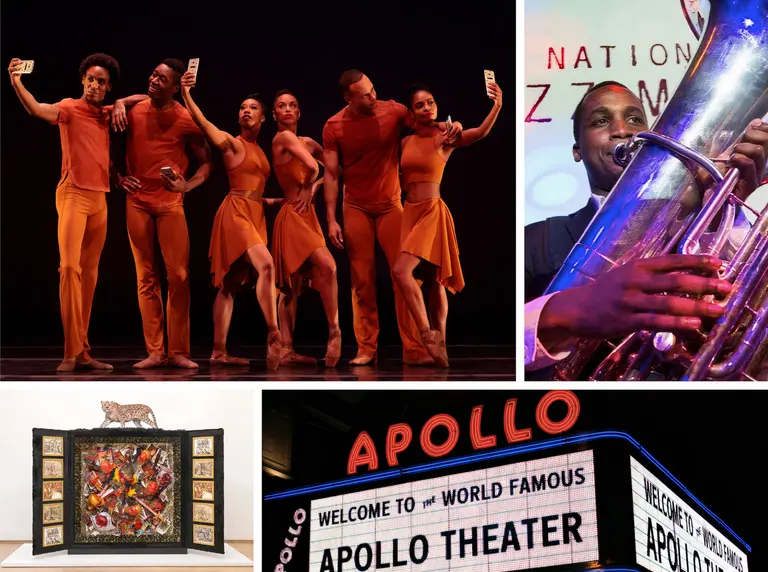

“A Ballad for Harlem,” the new exhibit now on view at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, explores the history of the neighborhood and celebrates Black placemaking in 20th and 21st century America. The exhibit uses photographs, manuscripts, objects, art and sculpture from the Schomburg’s collection to revisit “Harlem’s places, people, and moments—both known and underrepresented—that capture the realities of community and hardship experienced by Black Americans.” Ahead, hear from curator Novella Ford to learn more about the show.

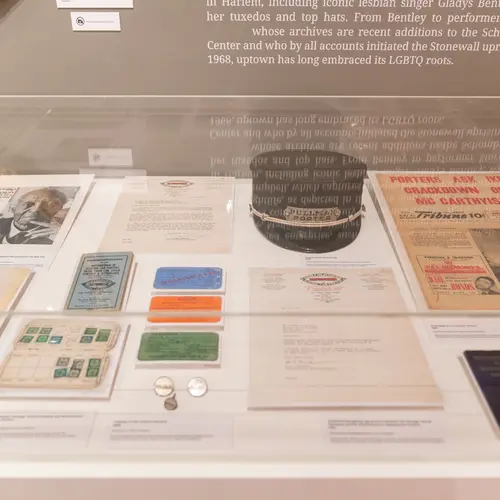

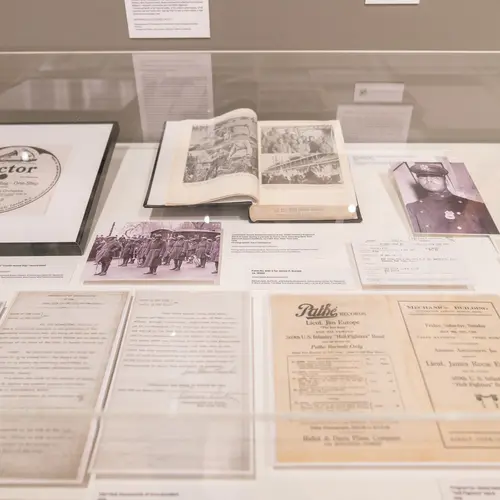

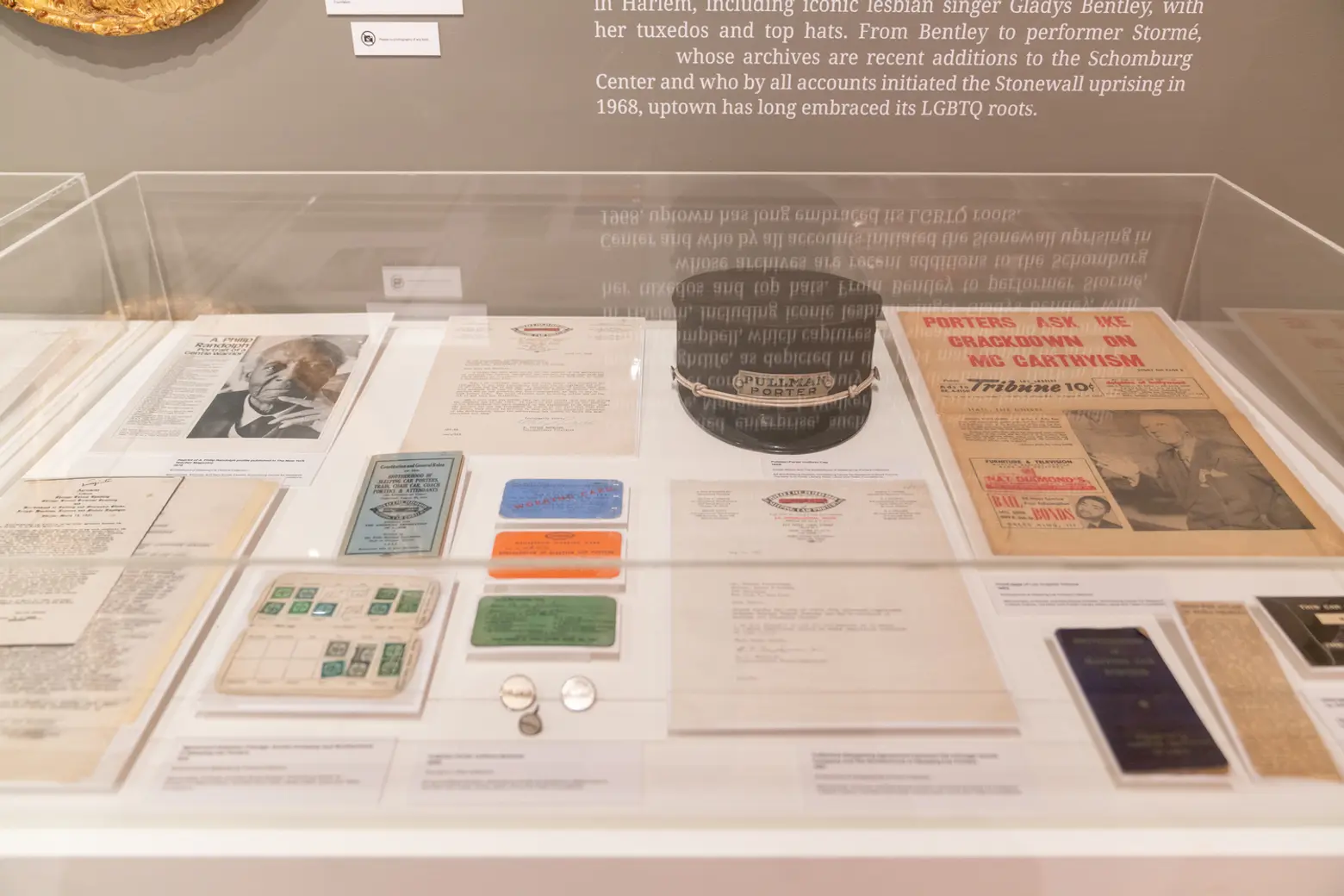

Items from the exhibition A Ballad for Harlem at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

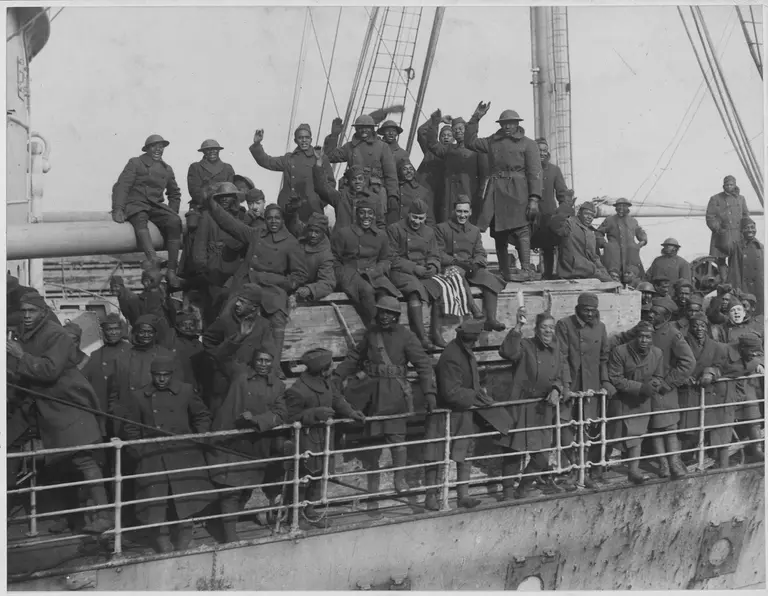

The exhibit includes such items as the personal working copy of Langston Hughes’ African Lady as it was set to music and maps to his historic spaces in Harlem; the commemorative plaque honoring Marcus Garvey’s first speech from the Speaker’s Corner on 135th Street, which took place in 1916; Gamin and Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp), bronze sculptures by Augusta Savage; flyers, business documents from the Clef Club, a musical society for Black musicians founded by jazz pioneer James Reese Europe; photographs, ephemera, and an audio recording from the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first Black labor union.

Novella Ford fills us in on more details about the show.

How did the idea for this exhibit come about?

NF: I have been working and living in Harlem for the last 10 years. Walking around I often remember little passages from books and essays with addresses and landmarks of black cultural figures who once called Harlem home. As I settled into my own Harlem routine, I became acquainted with my neighbors, discovered my own landmarks, and started to compare and contrast what I learned. My thought was, this is how one becomes part of the community; you find your groove within the community’s groove. I had a working knowledge of Harlem’s past—one that I held dear, passed down to me from my grandparents—and another fashioned after my current experiences.

The goal was to find a way to help visitors develop a working knowledge of one aspect of Harlem’s past that was rooted in Black placemaking and facilitate a dialogue about the type of gentrification we are experiencing in places like Washington, DC, and Harlem that can be devastating to the fabric of a community.

Items from the exhibition A Ballad for Harlem at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

How did you choose which items to include in the exhibit?

For the past two years, the Schomburg has been acquiring material through its Home to Harlem initiative, in an active effort to preserve and share resources that honor Harlem’s legacy. In addition to showcasing some of those items, I was interested in exhibiting treasures from individuals and organizations held within the Schomburg’s collections; materials less well-known that told a history pertinent to Harlem and Black placemaking around the U.S. Our division curators and librarians are a wealth of knowledge and a great resource for mining ideas and discovering archival gems.

In the exhibition, visitors will see maps, envelopes, and references to addresses. I wanted to make the experience tangible, so when you left the Schomburg you could find your way to one of those sites and reflect on what was and the implications of what may come.

What do you hope viewers and visitors will take away from the exhibit?

For me, the underlining goal of this exhibition is to support historical literacy, offering community members, tourists, supporters, and the like, a glimpse into Harlem’s past that resonates deeply with the present and shares expectations for Harlem’s future.

Items from the exhibition A Ballad for Harlem at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Was there a part of the process of mounting this exhibit that was especially moving, meaningful or surprising for you?

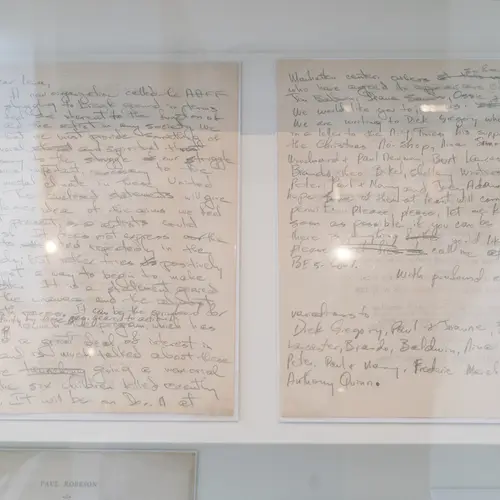

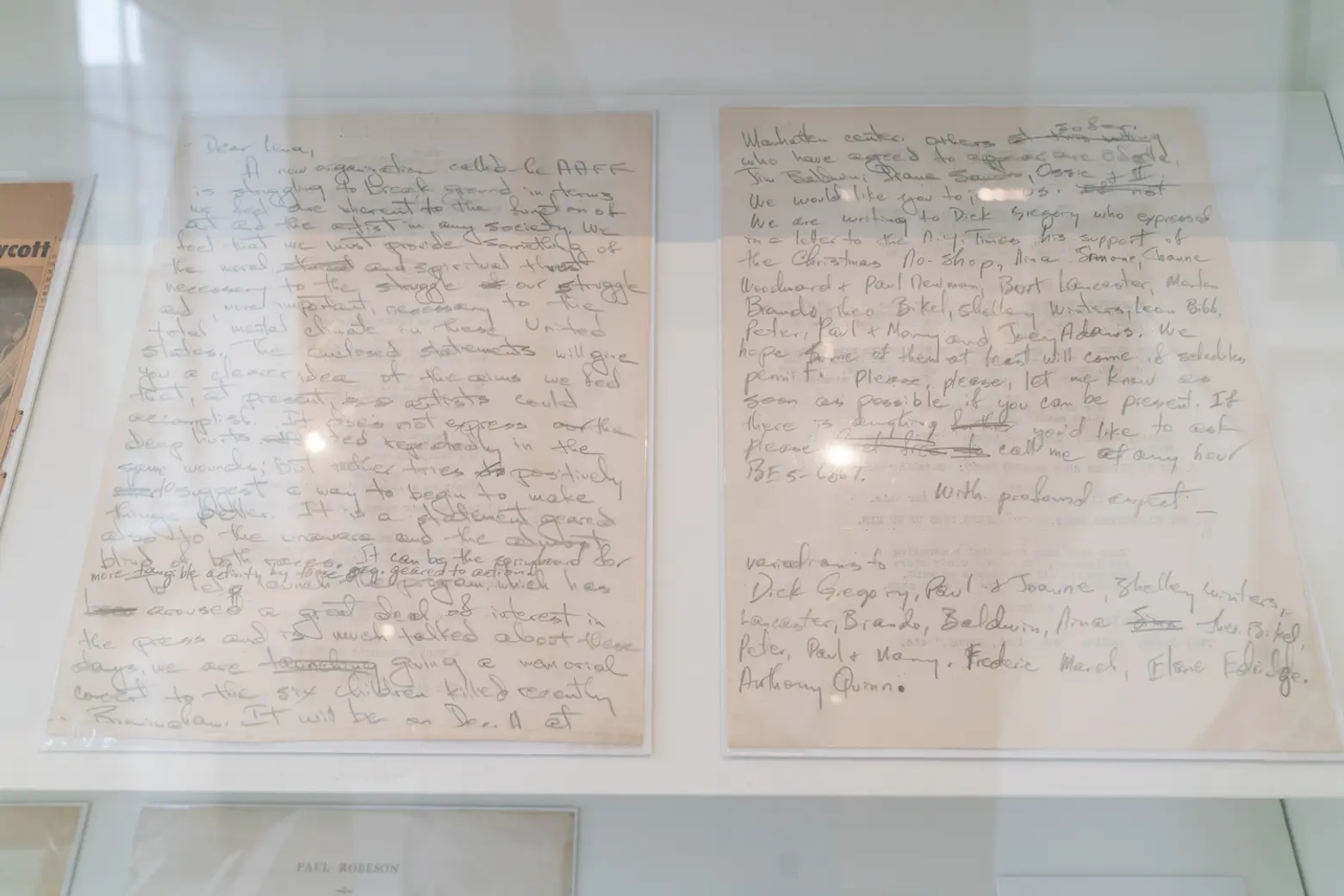

NF: I am new to curating so the entire process was meaningful, surprising, and moving: Learning about Althea Gibson’s roots in Harlem; seeing the handwriting of legendary artists; reading clear and passionate responses to injustice by Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis and watching how they rallied other creatives in the fight for freedom; understanding the role of black librarians; discovering groups like the Harlem Honeys and Bears Swim team; listening to A. Philip Randolph’s steady voice command the audience at the Brotherhood Sleep Car Porter’s meeting. It’s all very moving and necessary.

Letter from Ruby Dee to Lena Horne about “a new organization called the A.A.F.F” Date Unknown Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee Papers Manuscripts Archives and Rare Books Division.

Since this exhibit chronicles both the history and the changing present of Harlem, how do you see the future of the neighborhood, and the Schomburg Center’s role in the community moving forward?

NF: Harlem will continue to evolve. The time is now for economic and social forces to align themselves to preserve the heart of Harlem; the heart is in the neighborhood’s seniors, its economic diversity and affordable housing, the preservation of traditions and legacy organizations, and building space for new traditions and institutions. The Schomburg Center is dedicated to the collection and preservation of that history. There’s an old adage: if you know better, you’ll do better. It’s an optimistic thought and although it doesn’t always come true, it’s an important starting point and the perfect place for the Schomburg Center to begin a shared dialogue with the community about Harlem’s past, present, and our shared future. We know that communities naturally evolve, how do we ensure that the tide does lift all boats? I hope to work on that idea through the exhibition and public programs in the Fall.

RELATED: