Uncovering Central Park: Looking back at the original designs for ‘New York’s greatest treasure’

All of the images in this post are included in “The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure,” and are courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives.

There are few things as beautiful as a sunset in Central Park, standing beside the reservoir at 90th Street, looking west, and watching the sun sink behind the San Remo then glitter through the trees on the park’s horizon, and finally melt into the water, its colors unspooling there like ink. That view, one of so many available in the park, can be credited to the meticulous planning by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, whose extraordinary vision made Central Park one of the finest urban oases on earth.

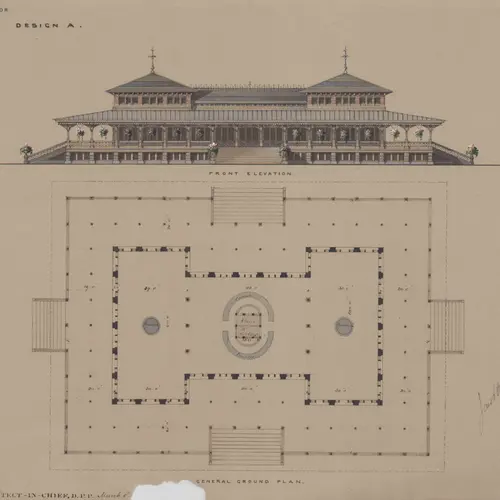

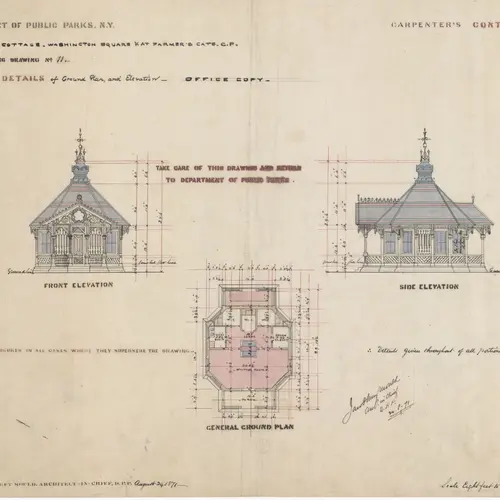

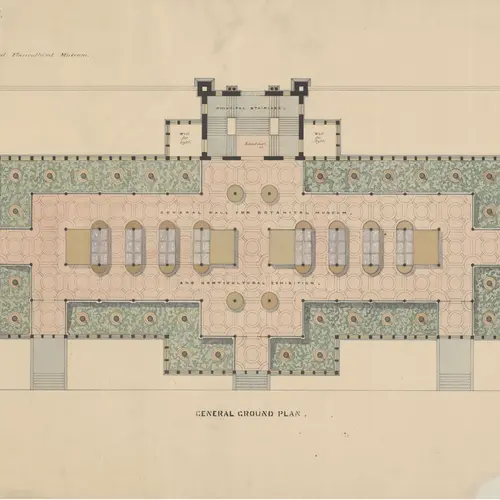

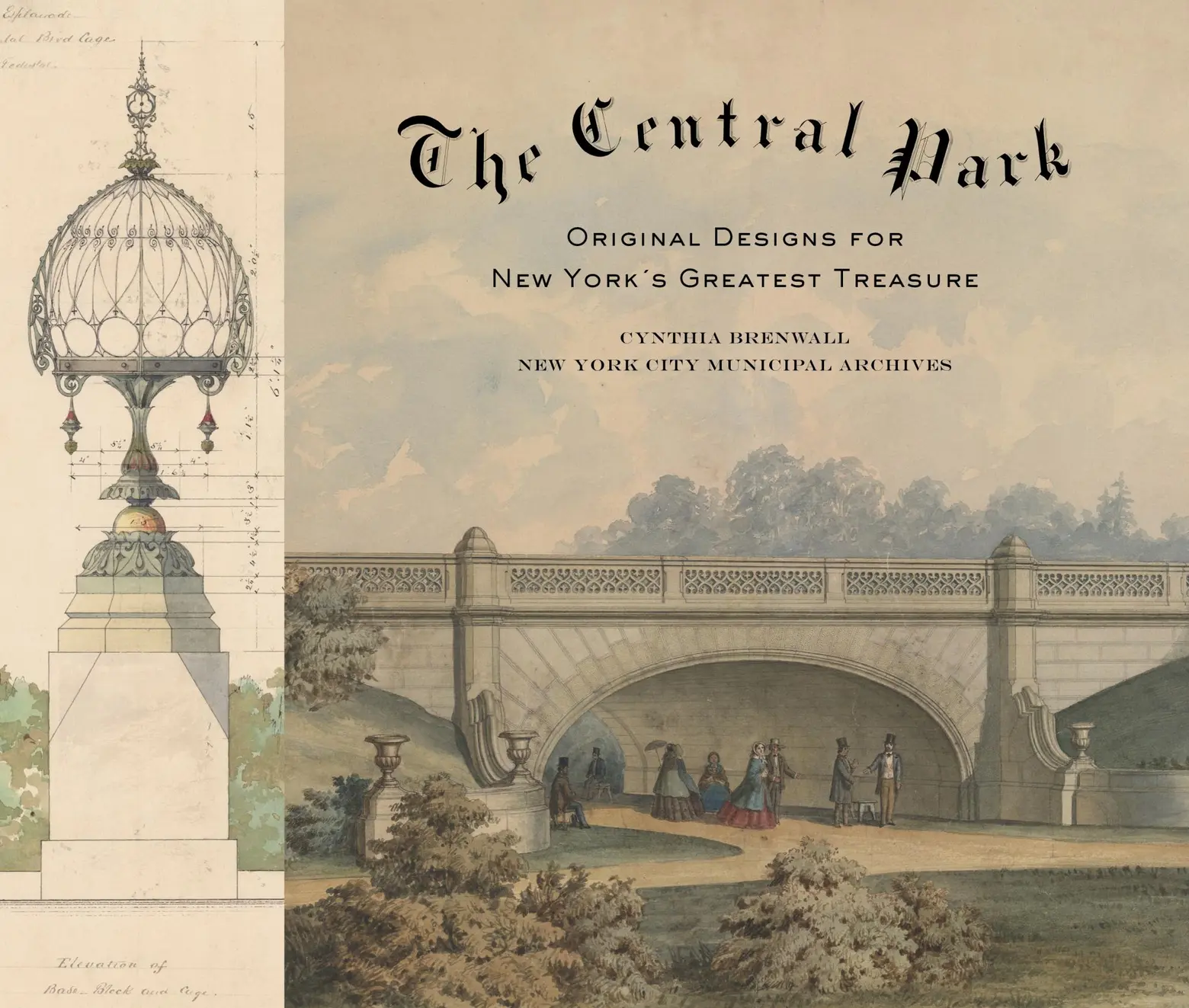

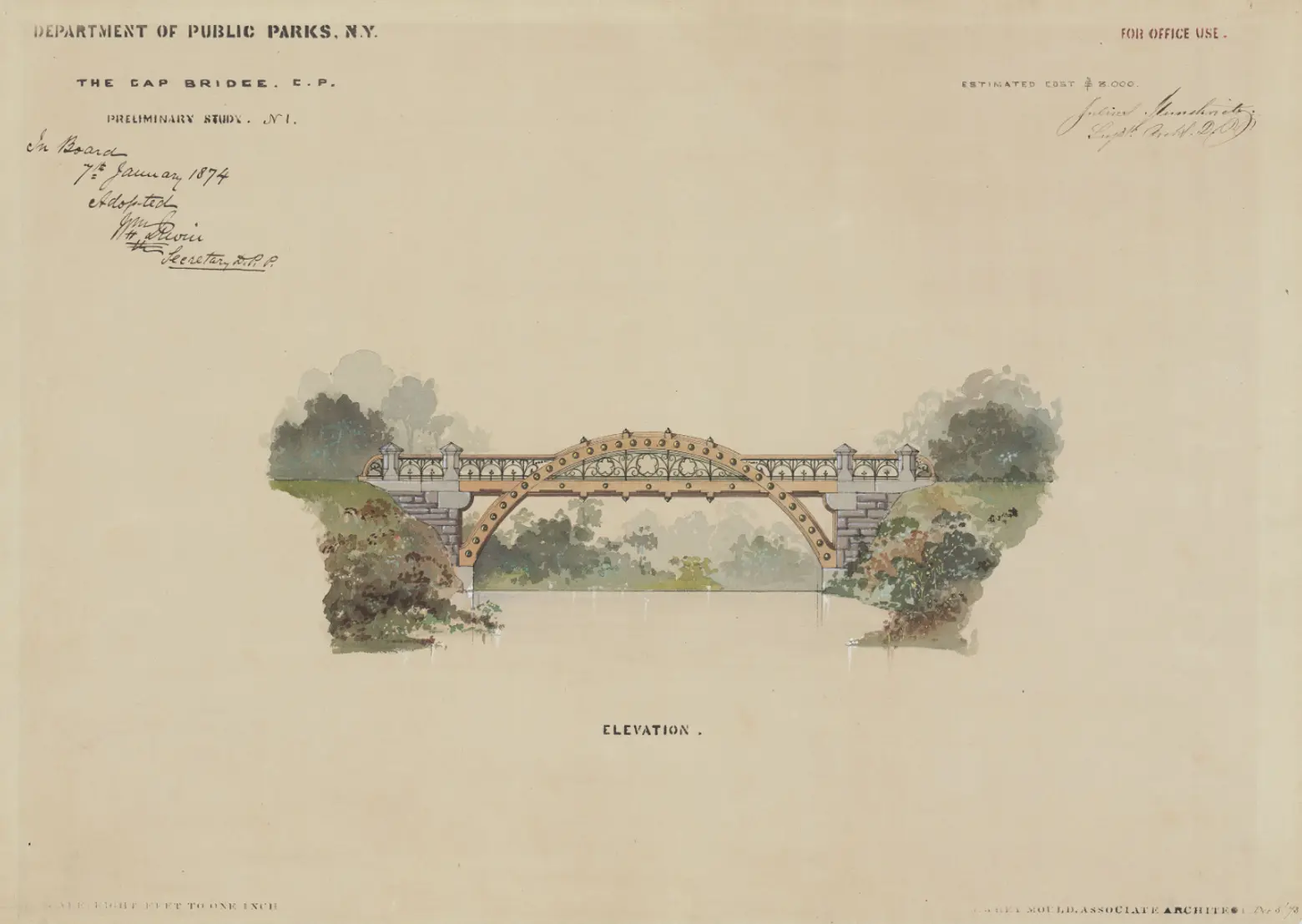

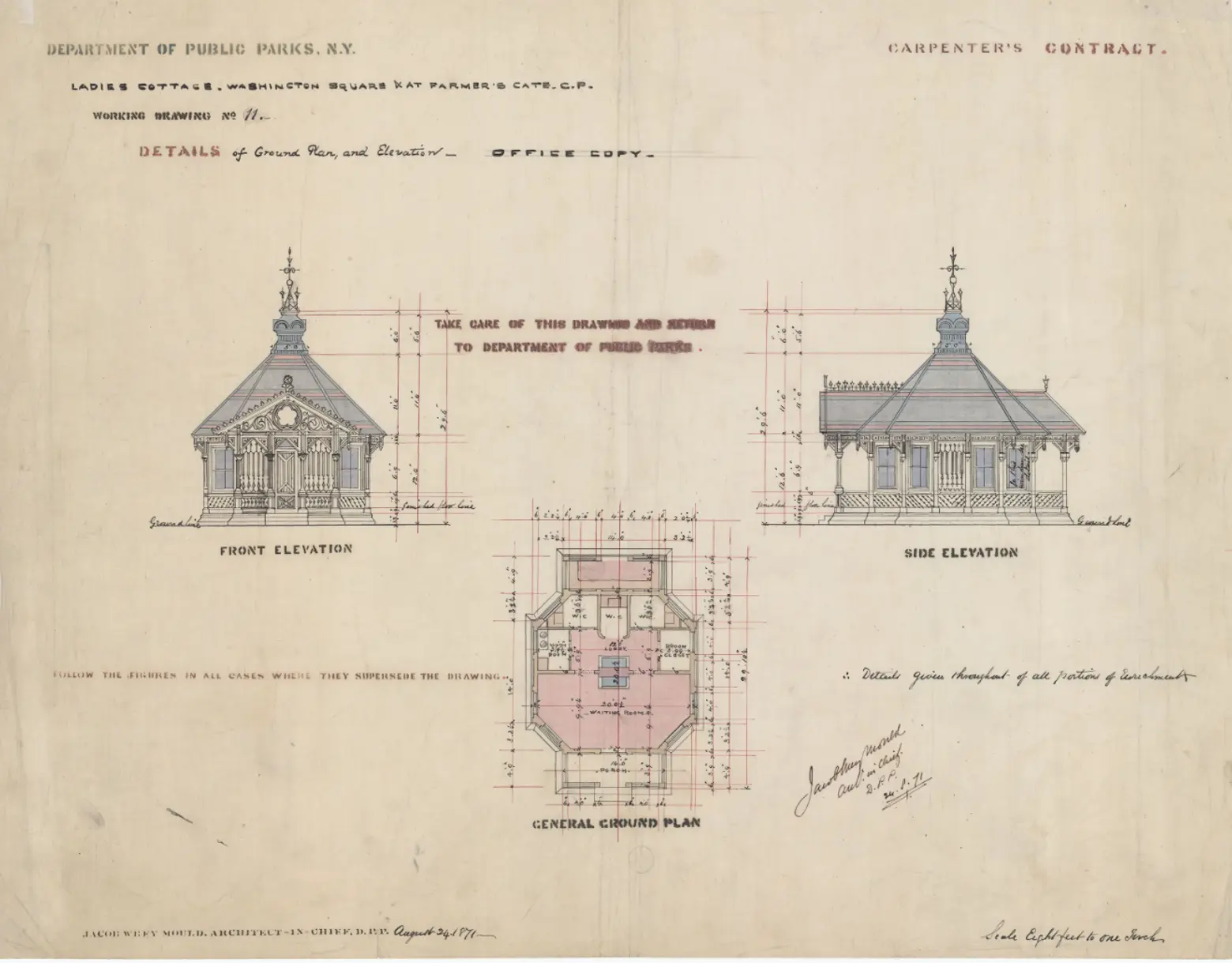

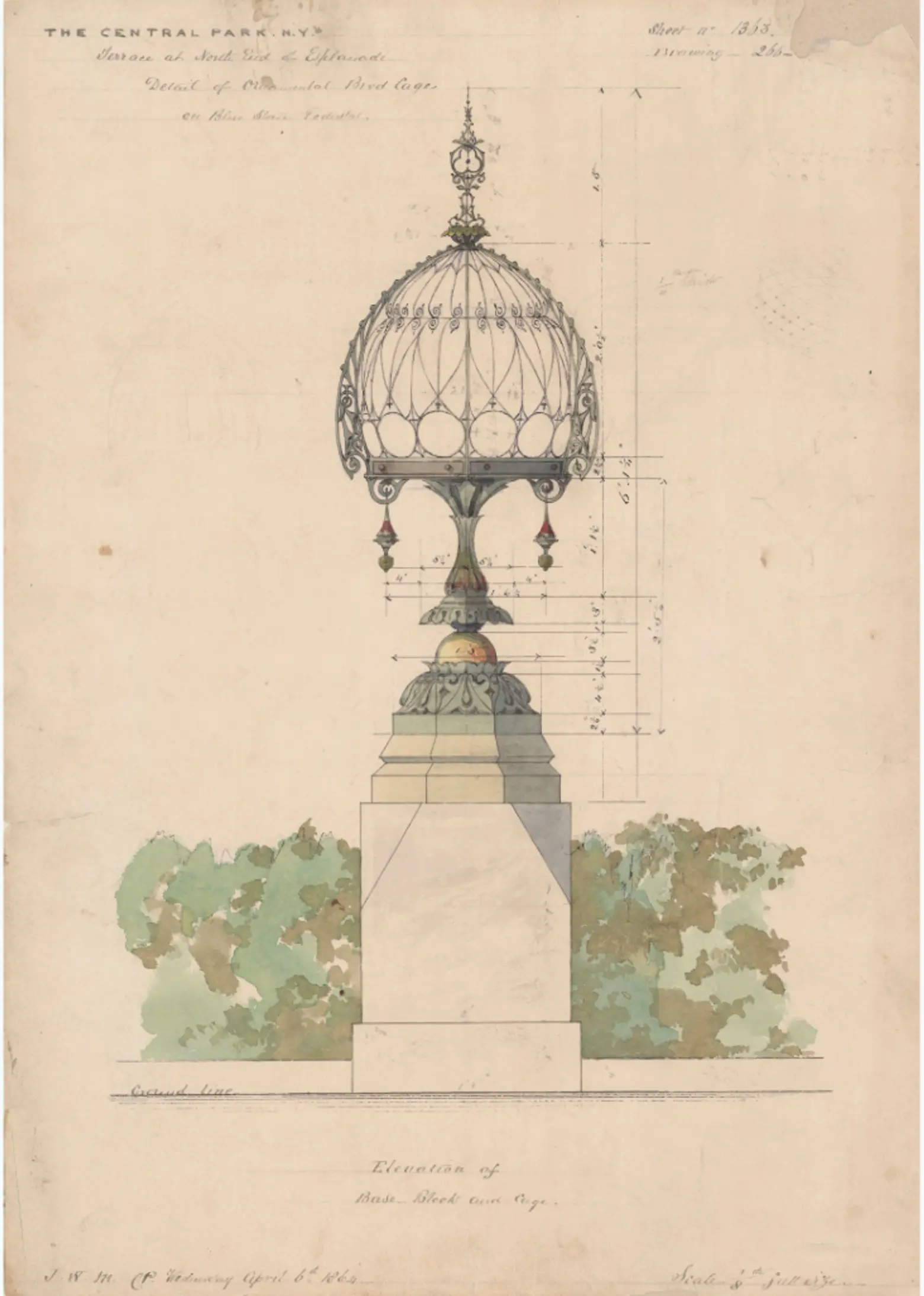

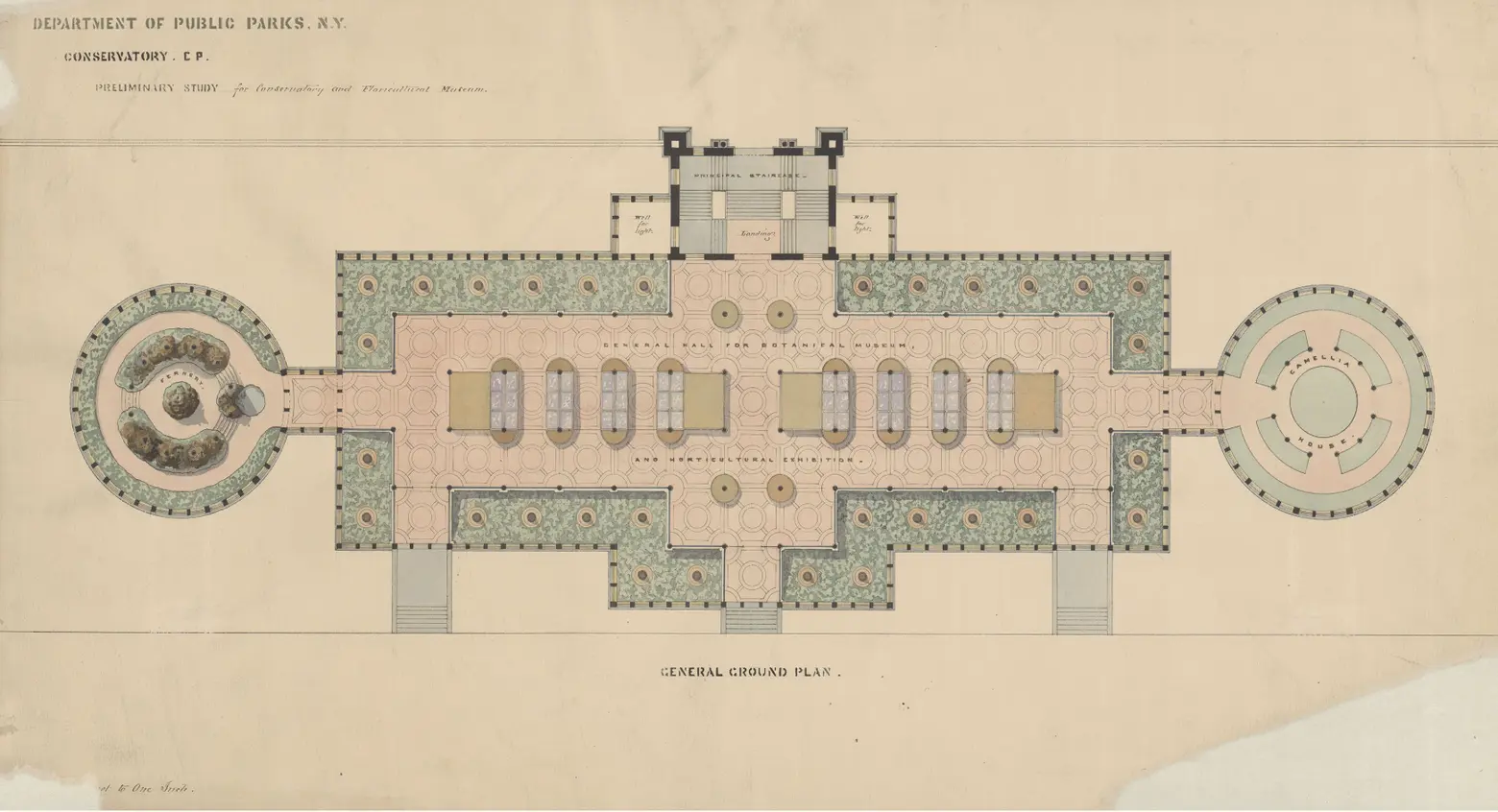

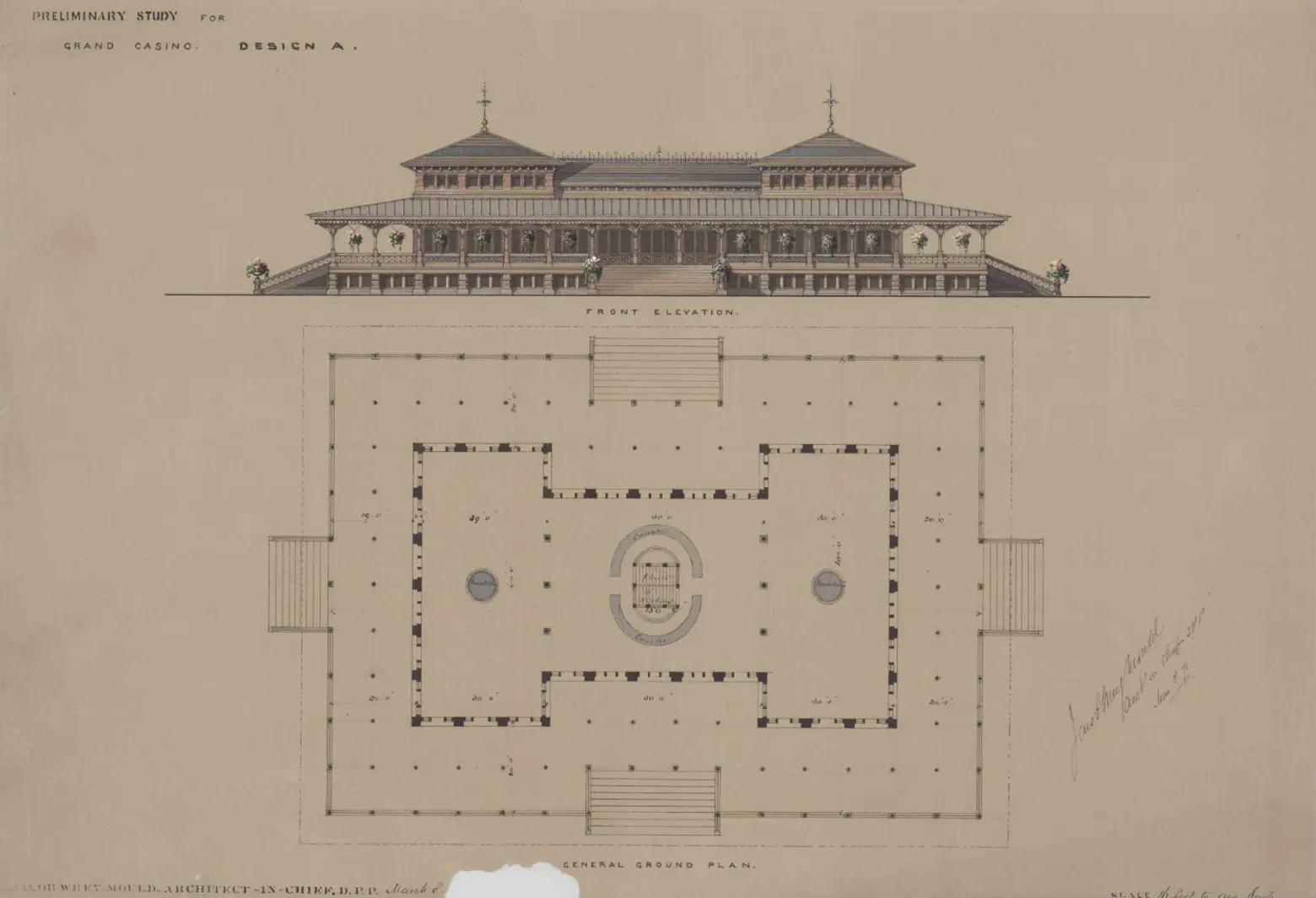

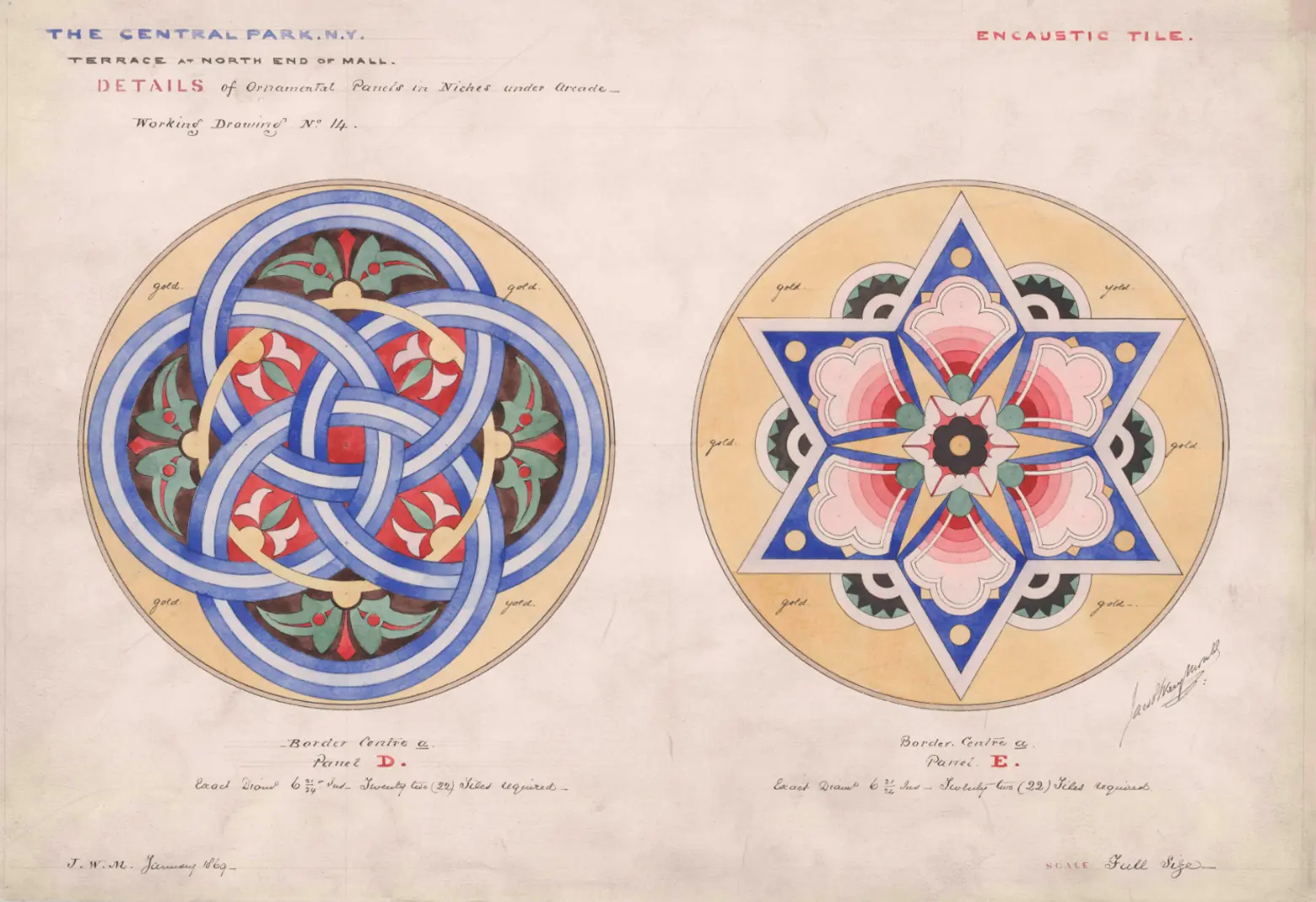

“The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure,” a new book by Cynthia S. Brenwall, out now from the NYC Department of Records, offers a closer look at that lanning process than ever before. Using more than 250 color photos, maps, plans, elevations, and designs — many published here for the very first time — the book chronicles the park’s creation, from conception to completion, and reveals the striking “completeness” of Olmsted and Vaux’s vision. “There was literally no detail too small to be considered,” Brenwall says. You’ll see the earliest sketches of familiar structures, and check out plans for unbuilt amenities (including a Paleozoic Museum!) 6sqft caught up with Brenwall to find out how the book came together, hear what it was like to cull through those incredible documents and snag a few secrets of Central Park.

The book grew out of a conservation project Brenwall began in 2012. She told 6sqft, “The topic of the book came out of a grant-funded project that I was hired to do for the archives in 2012…The Municipal Archives received a grant from the New York State Library to do conservation treatments of 132 Central Park drawings that had recently come into the collection as well as to catalog and digitize our full collection of over 3,000 Parks Department drawings. Because I was seeing each individual drawing as well as the collection as a whole, I was able to really see both the beauty of the drawings and the astonishing ‘completeness’ of the designs for the park.”

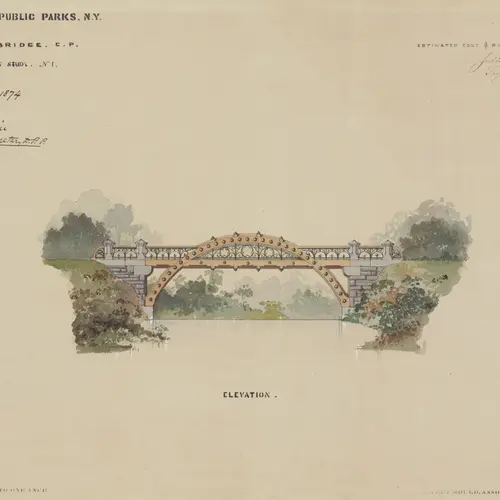

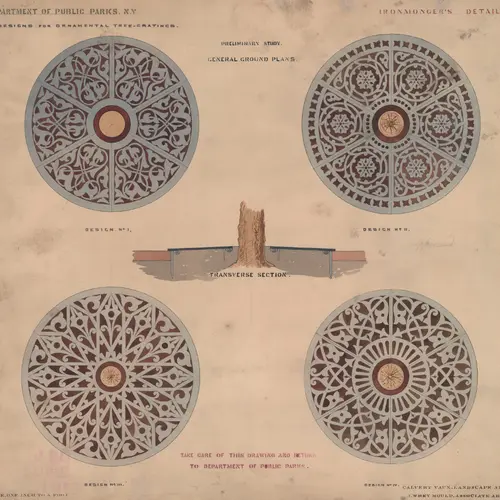

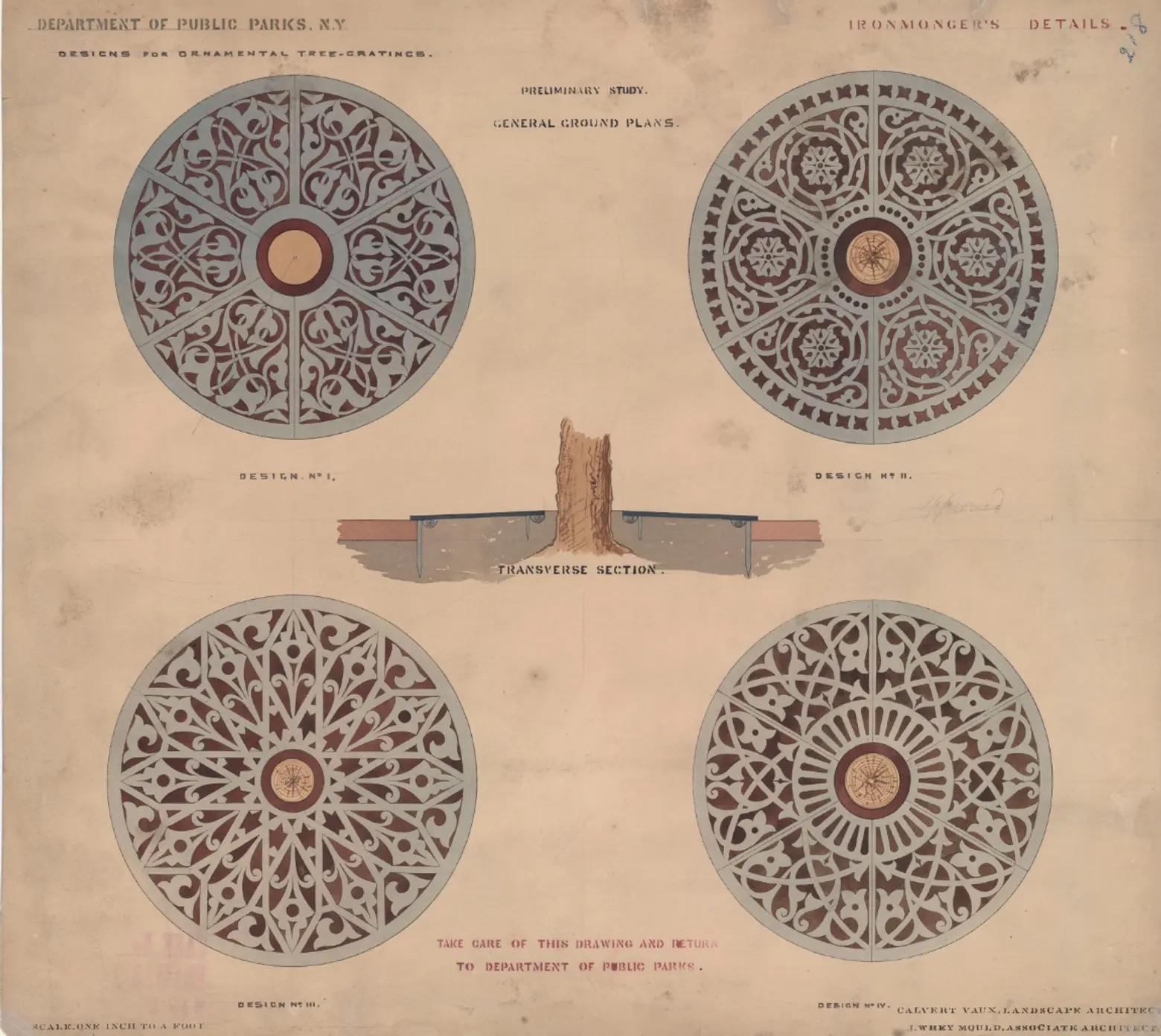

In the book, Brenwall complements the visually complete selection of images with a richly researched history of the park. She explained, “My knowledge of architectural history and research skills were an important part of getting the story right and tracking down many of the fun and obscure details that were included…like the fact that the ornamental tree gratings were a new technology that was developed in Paris and was being used for the first time in the United States.”

Olmsted and Vaux submitted their celebrated Greensward Plan for Central Park in 1857, but their vision is just as profound in 2019 as it was more than 150 years ago. Brenwall contends, “there is something special in Vaux and Olmsted’s vision of a beautiful and open space for every New Yorker, regardless of income or social class that really resonates today. The park was meant as a respite from the encroaching city as well as a place for culture and ‘healthful exercise’ as the designers called it. I hope that readers can see how a park designed and built in the mid-1800s still serves its original purpose and how important that purpose is even today.”

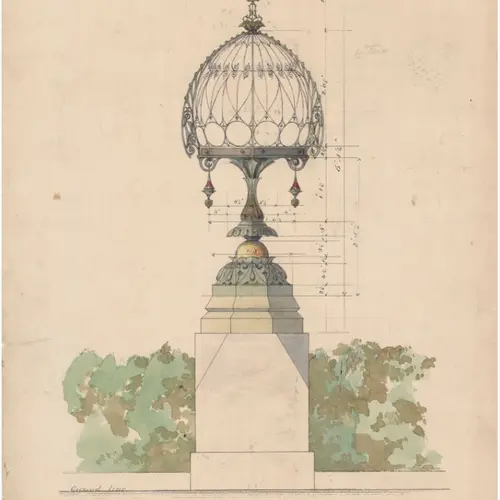

That civic-minded approach really informed Olmsted and Vaux’s plans. They considered and tried to meet the needs of Gaslight New York. For example, “there were elaborate drinking fountains located inside some the underpasses of the bridges and… the drinking fountains at the upper part of the Mall and Terrace had hidden blocks of ice lowered underneath them so that park visitors could have cool drinking water throughout the summer.”

But human park-goers weren’t the only ones who needed refreshment. Olmsted and Vaux also designed drinking fountains for horses. Brenwall highlighted a design for one such fountain as “a prime example of how the designers thought of everything. If it was going to go into the park it had to be beautiful and well designed. The fountain is still in the park at Cherry Hill, although the final version was a bit less colorful than the original plans.”

But, then as now, even the most civically virtuous ideas were sometimes waylaid by politics, which brings us to the juicy issue of Boss Tweed vs. the Paleozoic Museum. Brenwall explains, “the building was started and then nixed when Boss Tweed and his cronies took over in 1870. The drawing showing what the dinosaurs were going to look like is a real gem, and the background story of why it wasn’t built includes a lot of political intrigue!”

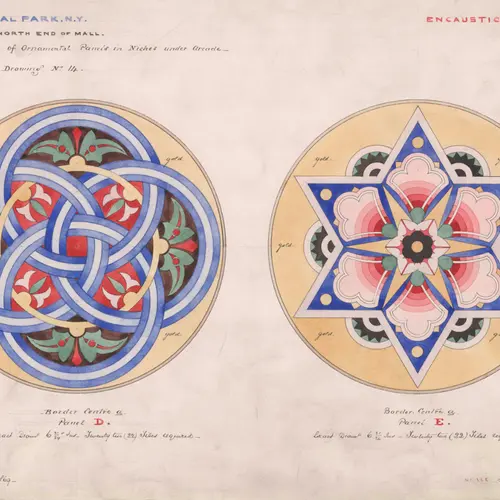

As for fun-facts, it turns out NYC Parks were rocking restaurants more than a century before Danny Meyer came to town. Brenwall reports, “At one point the Terrace Arcade served as a restaurant with tables and a service counter set up underneath those gorgeous Minton Tiles! There are a million little stories like this that I hope, when paired with the drawings, will give a fuller history of the park and the city.”

To get the full history, you can purchase the book here.

RELATED:

- An archive of 24,000 documents from Frederick Law Olmsted’s life and work is now available online

- A rejected design for Central Park from 1858 shows colorful, whimsical topiaries

- From natural history museum to municipal weather bureau: The many lives of Central Park’s Arsenal

- Billy goats and beer: When Central Park held goat beauty pageants