The Lower East Side’s forgotten Lung Block: The Italian community lost to ‘slum clearance’

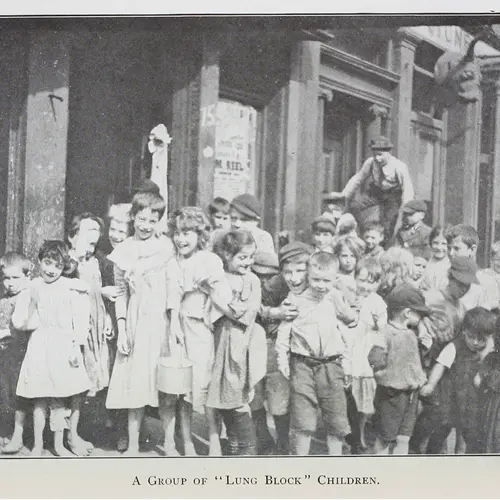

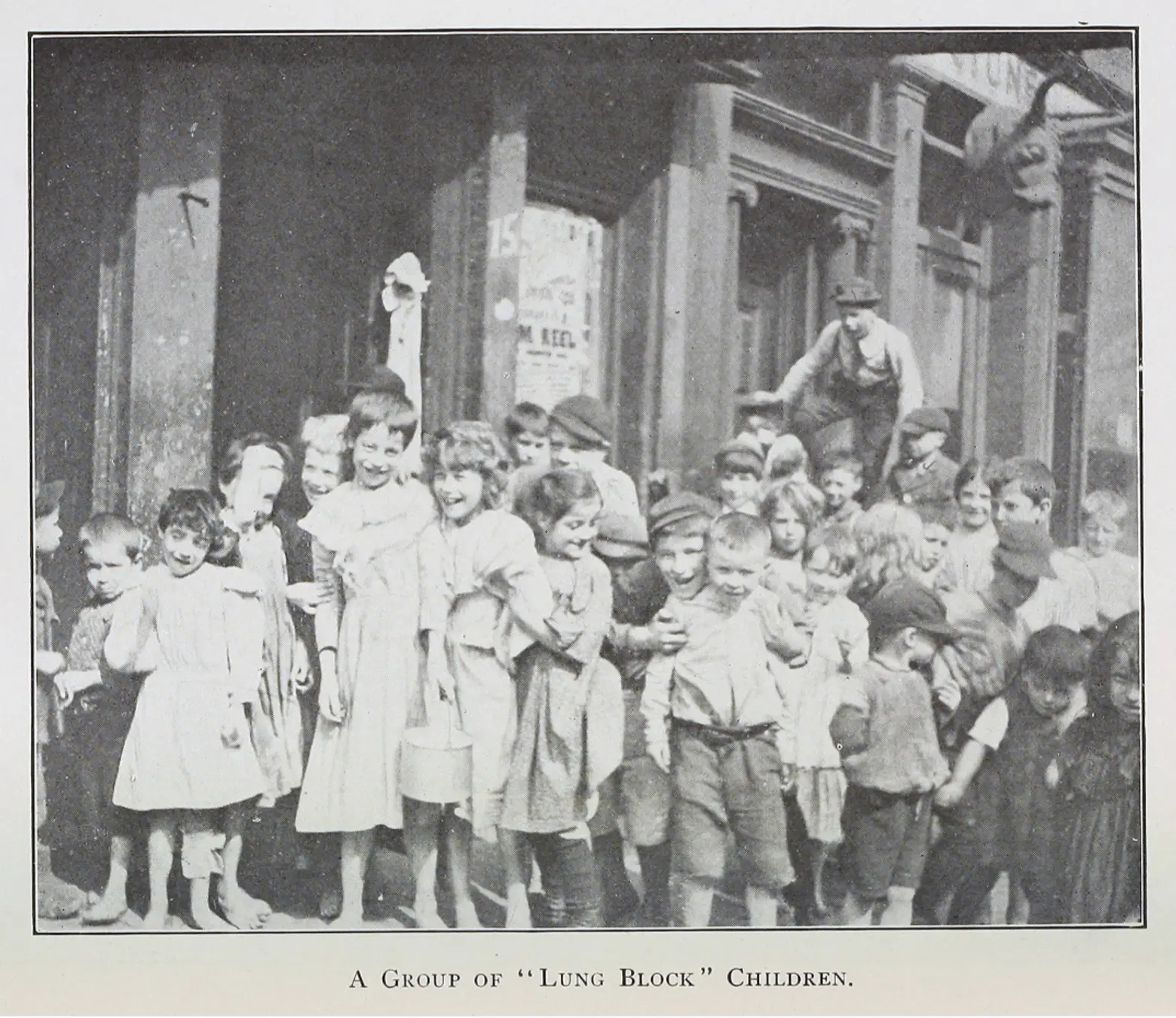

“A Group of ‘Lung Block’ Children,” from Ernest Poole, The Plague in Its Stronghold, Tuberculosis in the New York Tenement, 1903. Courtesy of the Department of Records

In 1933, a new development rose on the Lower East Side. It was Knickerbocker Village, the first federally-funded apartment complex in the United States, and one of the first developments that would later fall under the umbrella of the city’s “Slum Clearance” program. The “slum” that Knickerbocker Village replaced wasn’t just any rundown collection of buildings – it was the notorious “Lung Block” between the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges, bounded by Cherry, Monroe, Market and Catherine Streets, which in 1903, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ernest Poole named the most congested and disease-ridden place in the city, or, perhaps, the world. But was it?

“The Lung Block: A New York City Slum and its forgotten Italian Immigrant Community,” a new exhibit opening April 25th at the NYC Department of Records curated by researchers Stefano Morello and Kerri Culhane, will revisit the neighborhood and the immigrant community that called it home. With maps, journals, photos and other artifacts, the exhibit will consider the connections between health and housing, affordability and gentrification, public health and progressive reform, and architecture and the immigrant experience.

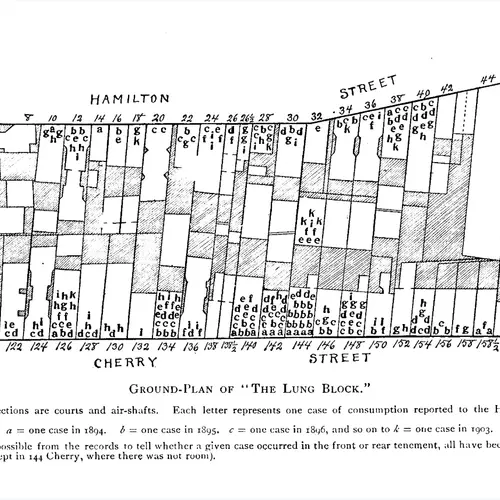

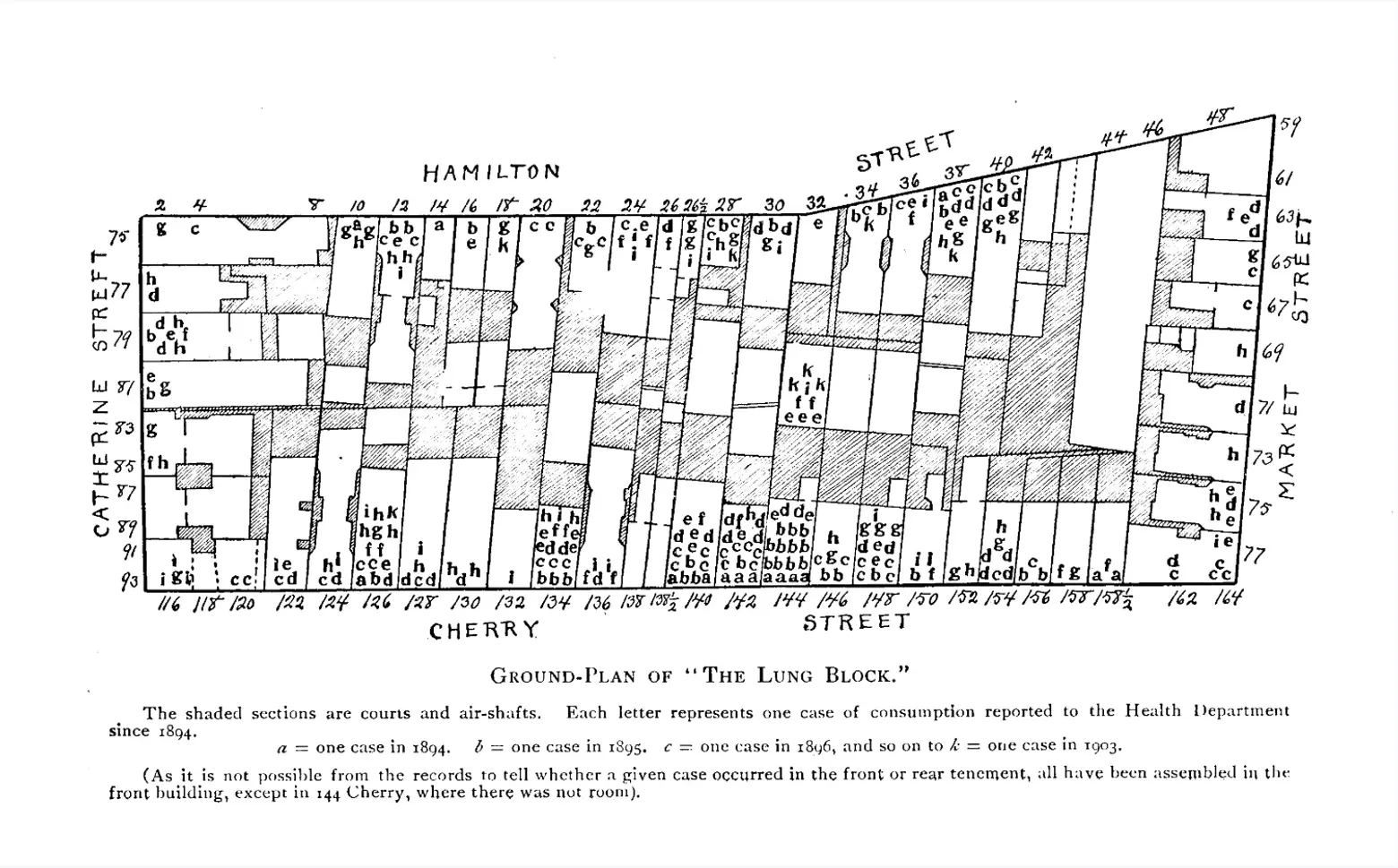

“Ground-Plan of the ‘Lung Block’,” from Ernest Poole, The Plague in Its Stronghold, Tuberculosis in the New York Tenement, 1903. Courtesy of the Department of Records

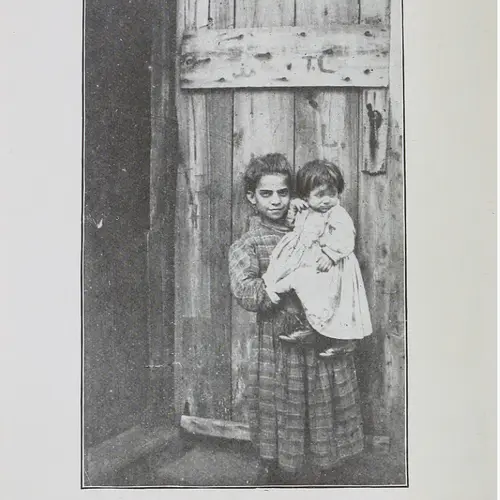

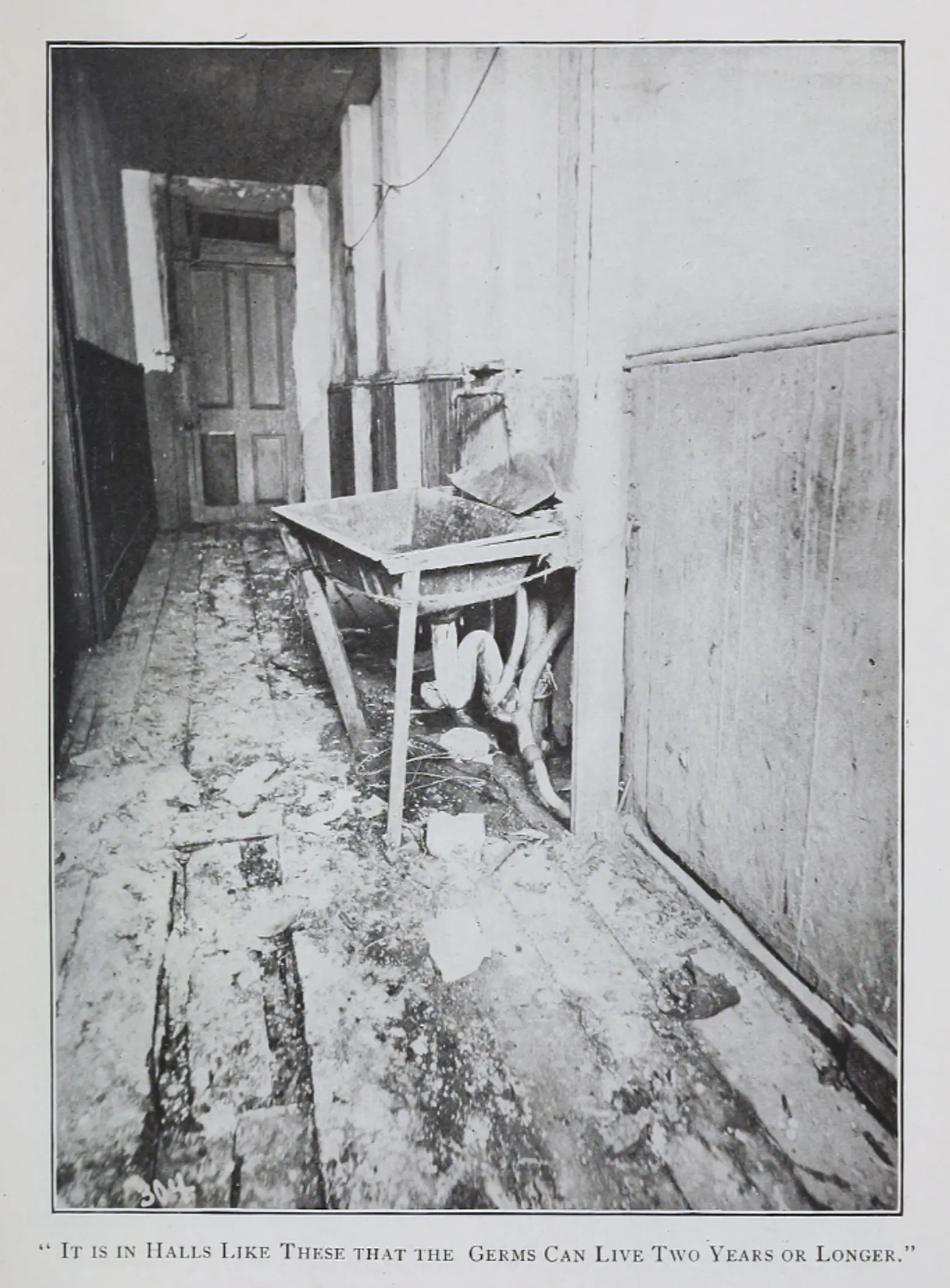

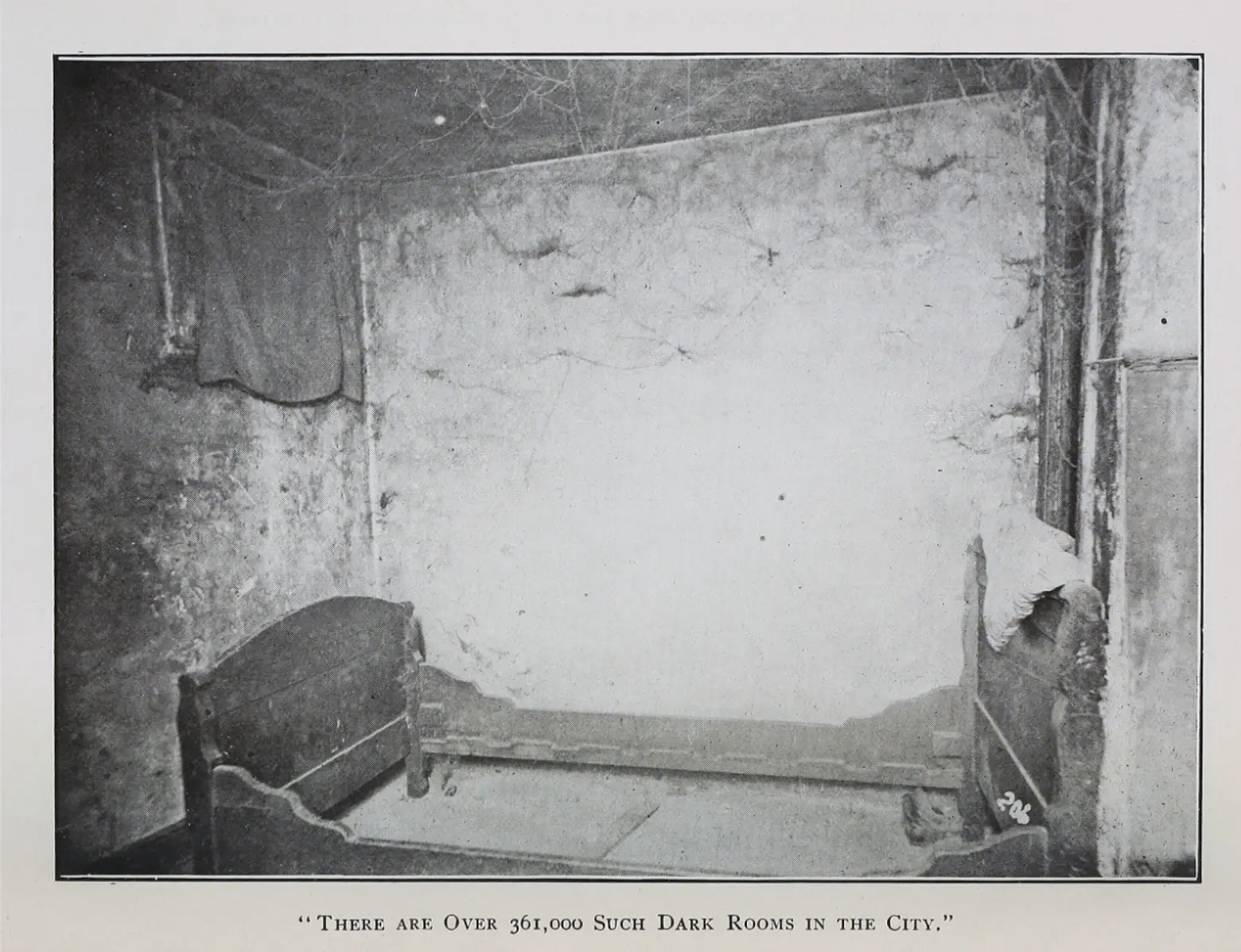

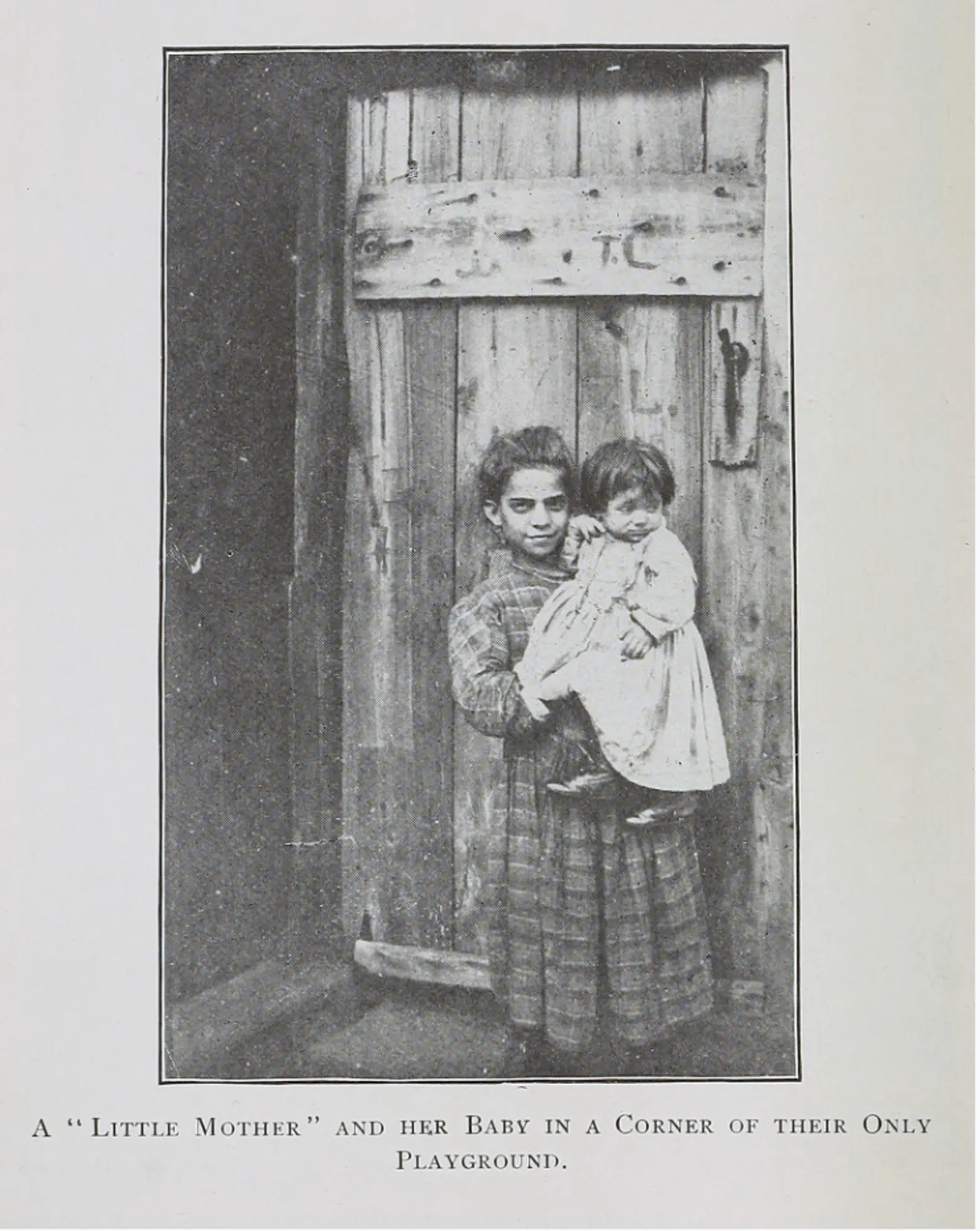

By 1933, a bustling Italian community had lived on Cherry, Monroe, Market and Catherine Streets for more than 40 years. Residents there lived cheek-by-jowl with millions of other immigrants who settled in New York at the turn of the 20th century and helped make the Lower East Side the most densely populated place in the world. At the time, immigrants on the Lower East Side faced extremely difficult living conditions and very real challenges: Their tenement homes provided little light, air, or ventilation, and many lacked even indoor plumbing. In such cramped quarters, disease spread quickly, and the most notorious of pathogens was “The White Plague” or tuberculosis.

A “Lung Block” was a generic name for anywhere that tuberculosis thrived. While the area between Cherry, Monroe, Market and Catherine Streets, was certainly a Lung Block, it was by no means the most tubercular in the city. In fact, between 1905 and 1915, tuberculosis was on the decline in the area. Nevertheless, it came to symbolize, to the concerned public of loftier precincts, the perils – both to one’s lungs and to one’s morals – of life in the city’s poorer quarters.

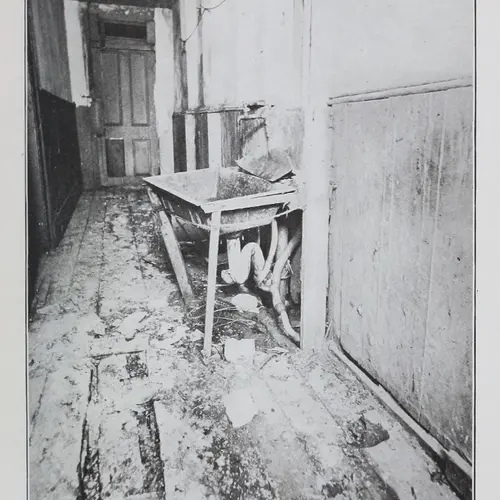

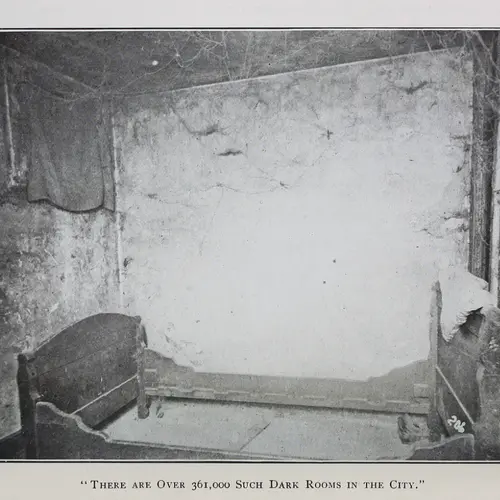

From Ernest Poole, The Plague in Its Stronghold, Tuberculosis in the New York Tenement, 1903. Courtesy of the Department of Records

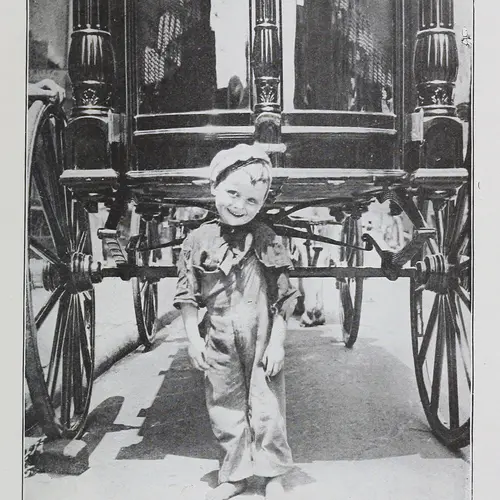

From Ernest Poole, The Plague in Its Stronghold, Tuberculosis in the New York Tenement, 1903. Courtesy of the Department of Records

Ernest Poole wrote that in the Lung Block, people “choked to death in…foul holes,” where “drunkenness, foul air, darkness and filth” fed the fatal engine of tuberculosis. In the Lung Block, he explained, “a thousand families struggled on, while many sank and polluted the others.”

The notion of a link between disease and social “pollution” was part of Victorian public health theory, which held that infectious diseases such as TB were caused by bad air but exacerbated by moral, cultural, or ethnic shortcomings. This narrative held that the Italian families of the Lung Block, for example, were particularly prone to disease, because of their “natural” inclination toward crime, ignorance, and poverty.

The purple prose in Poole’s account helped define the Lung Block as one of the most outrageously degraded neighborhoods in the world. That narrative took hold amongst Progressive reformers of the era. For example, Robert De Forest, head of the 1901 Tenement Commission, said of the neighborhood, “I know of no other tenement house block in this city, which is so bad from a sanitary point of view, or from a criminal point of view. Every consideration of public health, morals and decency require that the buildings on this block be destroyed at an early date.”

The idea was that the medical ills, as well as the social ills, real or imagined, that proliferated amongst the city’s immigrant populations and its working poor could begin to infect the city at large, and must, therefore, be eradicated as quickly as possible.

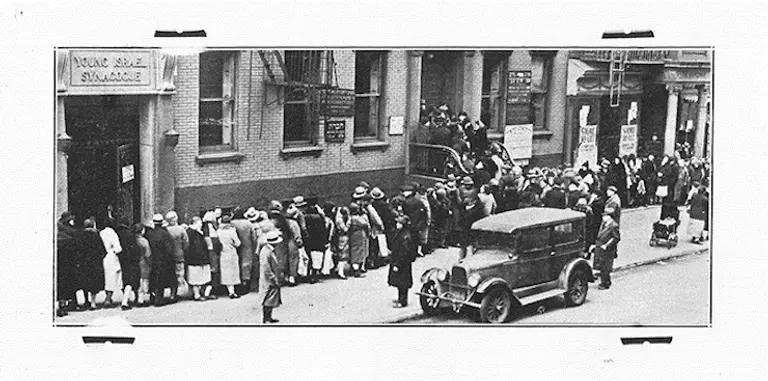

From Ernest Poole, The Plague in Its Stronghold, Tuberculosis in the New York Tenement, 1903. Courtesy of the Department of Records.

The notion that immigrant communities were an inherent threat to the city was racist and unfounded, but the need for housing reform was real. It is an absolute fact that nobody should be forced to live without light, air, ventilation, or clean water, and no one should live under the constant threat of disease. The tension between the genuine need for housing reform, and the call to raise whole communities, is one that the city struggles with to this day.

But, at the turn of the 20th century, Slum Clearance was not the only option on the table when it came to housing reform. Instead, architects including Henry A. Smith constructed “model tenements” such as the Cherokee Apartments in Yorkville, which opened in 1912, and endeavored to bring light and air into the dank hallways and stairwells that characterized traditional tenements. Details such as skylights, triple hung windows, and side ventilation helped circulate air in ways never before seen in low-income housing.

But Smith himself considered the Model Tenement movement to be a failure, because while the buildings were “healthful and hopeful things to look upon” they did not improve the living conditions of the very poor, who, in most instances, could not afford to live in them. He understood that “beautiful apartments at more than $12 a month mean nothing to the family that can only afford to pay $10,” let alone many of the families on the Lung Block, who paid $5.

From Ernest Poole, The Plague in Its Stronghold, Tuberculosis in the New York Tenement, 1903. Courtesy of the Department of Records.

From Ernest Poole, The Plague in Its Stronghold, Tuberculosis in the New York Tenement, 1903. Courtesy of the Department of Records.

One issue that Smith identified was that Model Tenements were financed by private philanthropy, and therefore built to needlessly expensive specifications. He suggested instead a public board of appeal for tenements. Further, he hoped that new buildings, rich in light, space, and air, would be maintained under commercial management so that they could be competitively rented, to keep costs down. He believed that while private philanthropists, such as the Vanderbilts who had financed the Cherokee Apartments, could, if they chose, operate their properties at a loss, and charge more affordable rents, such pure charity would not be a sustainable way to create long-term housing reform.

Unfortunately, Smith’s plan for publicly funded, commercially maintained, competitively priced, healthful and safe low-income rental housing was waylaid by the Great Depression: When the economy tanked landlords on the Lower East Side saw their holdings decline in value. The solution they sought was to redevelop the area with middle-class housing, for which they could charge more money. At the same time, the federal government’s New Deal legislation was making funds available for developers to do just that.

The developer Fred. F. French, who had also created Tudor City, saw his opportunity. French began buying the land between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In 1932, he appealed for funds from the New Deal’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation and received money to build Knickerbocker Village. The lung block was razed, and Knickerbocker’s 1,590 apartments rose in their place.

Destruction of the Lung Block, 1933. Courtesy New York Public Library, Fred F. French Collection. Via the Department of Records.

French was aware he had pulled off a coup. He told a gathering of students at Princeton, “Our company, strangely enough, was the first business organization to recognize that profits could be earned negatively as well as positively in New York real estate–not only by constructing new buildings but by destroying, at the same time, whole areas of disgraceful and disgusting sores.”

It was true that the Lung Block’s original buildings were “disgraceful” in design because they did not promote the health and safety of their residents. But, however more clean Knickerbocker’s new apartments were, they did not help the people whose homes had been destroyed. As Anthony Jackson wrote in “A Place Called Home,” his study of Manhattan’s low-income housing, four-fifths of families who had lived in the Lung Block moved into other nearby tenements, facing the same conditions they had been forced out of.

“A ‘Lung Block’ Resident,” from Ernest Poole, The Plague in Its Stronghold, Tuberculosis in the New York Tenement, 1903. Courtesy of the Department of Records.

Morello and Culhane’s new exhibit at the Department of Records will explore who those families were, and consider their pivotal place in the city’s ongoing debate around affordable housing, municipal reform, and livable space.

RELATED: