12 social change champions of Greenwich Village

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the designation of the Greenwich Village Historic District. One of the city’s oldest and largest landmark districts, it’s a treasure trove of rich history, pioneering culture, and charming architecture. Village Preservation will be spending 2019 marking this anniversary with events, lectures, and new interactive online resources, including a celebration and district-wide weekend-long “Open House” starting on Saturday, April 13 in Washington Square. Check here for updates and more details. This is part of a series of posts about the Greenwich Village Historic District marking its golden anniversary.

Few places on Earth have attracted more or a broader array of activists and agitators for social change than Greenwich Village. And much of that activity took place right in the heart of the neighborhood in the Greenwich Village Historic District, where that rich history has been preserved through landmark designation for the past half-century. Here are just a few of the many who lived within its bounds and toiled to make the world a better or more just place.

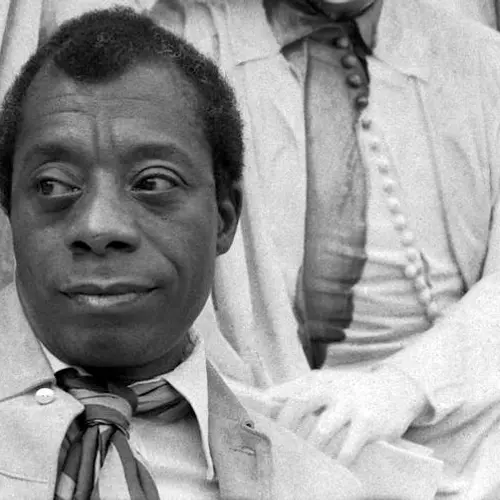

Photo of James Baldwin via Wikimedia

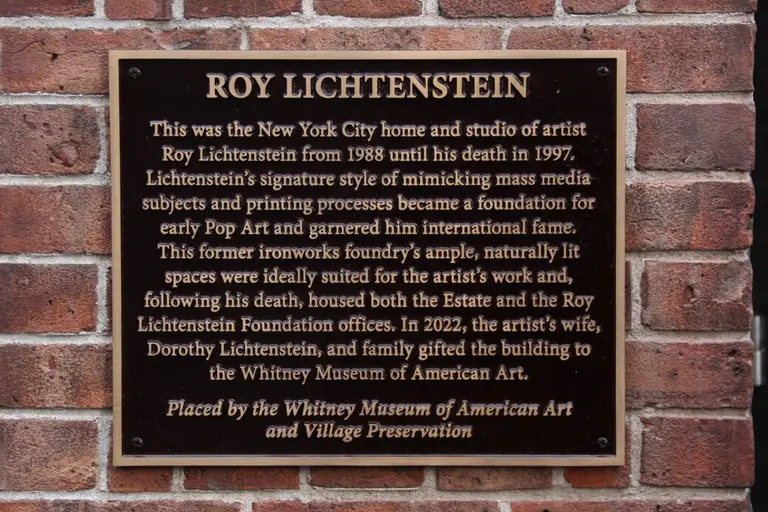

1. James Baldwin

James Baldwin was born in Harlem in 1924 and became a celebrated writer and social critic in his lifetime, exploring complicated issues such as racial, sexual, and class tensions. Baldwin spent some of his most prolific writing years living in Greenwich Village and wrote of his time there in many of his essays, such as “Notes of a Native Son.”

Many of Baldwin’s works address the personal struggles faced by not only black men but of gay and bisexual men, amid a complex social atmosphere. His second novel, “Giovanni’s Room,” focuses on the life of an American man living in Paris and his feelings and frustrations with his relationships with other men. It was published in 1956, well before gay rights were widely supported in America. His residence from 1958 to 1963 was 81 Horatio Street.

Baldwin became particularly outspoken during the 1960s about issues of justice and race, challenging the liberal establishment’s measured response to the civil rights movement. At the famous Baldwin-Kennedy meeting in 1963, Baldwin and a delegation of civil rights leaders challenged then-Attorney General Bobby Kennedy to do more and to understand more deeply the oppression African-Americans faced.

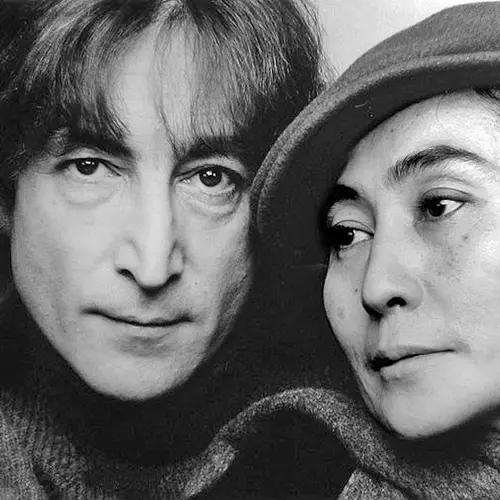

Via Wikimedia

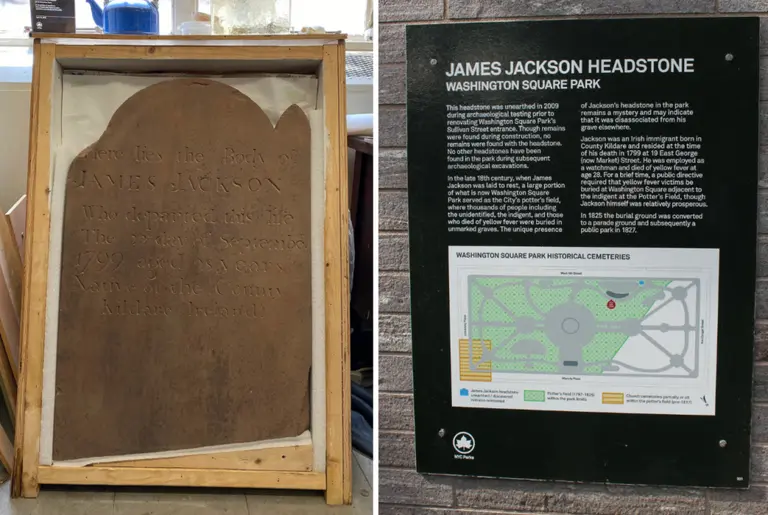

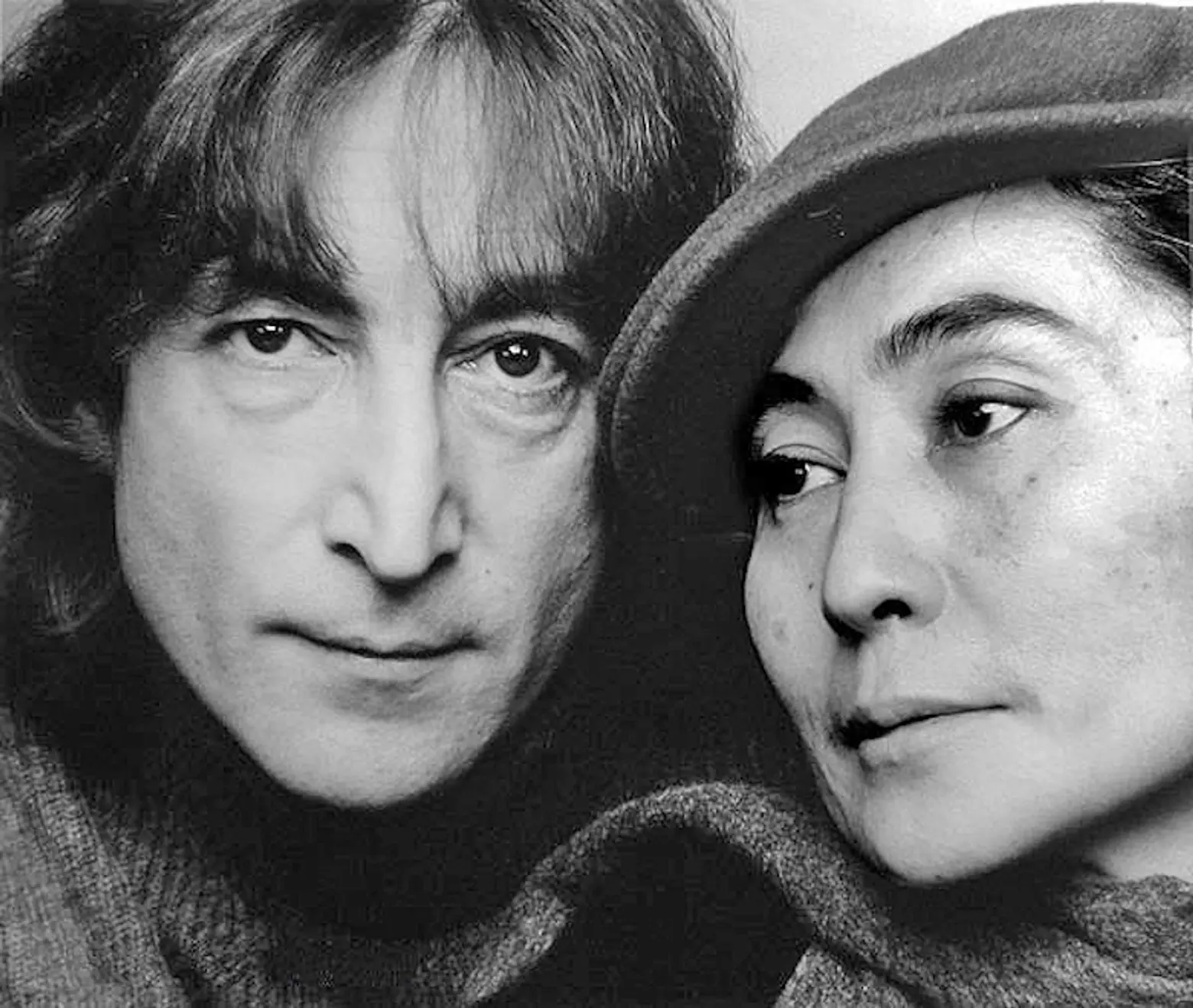

2. John Lennon

Lennon was almost as well known for his political activism and beliefs as his music and sometimes combined the two. He turned his honeymoon with wife Yoko Ono in 1969 into political theater by staging a “Bed-In for Peace” in Amsterdam, which they repeated three months later in Montreal. During that performance, he wrote and recorded “Give Peace A Chance,” which became an anthem of the anti-war movement. Later that year he and Ono paid for billboards in ten cities around the world which said: “War Is Over, If You Want It.”

Lennon also supported drug decriminalization, the Black Panthers, the Irish cause in Northern Ireland, and the budding gay rights movement by contributing a poem to The Gay Liberation Book in 1973. For his efforts, President Nixon sought to have him deported. From 1971 to 1972, he and wife Yoko Ono lived at 105 Bank Street.

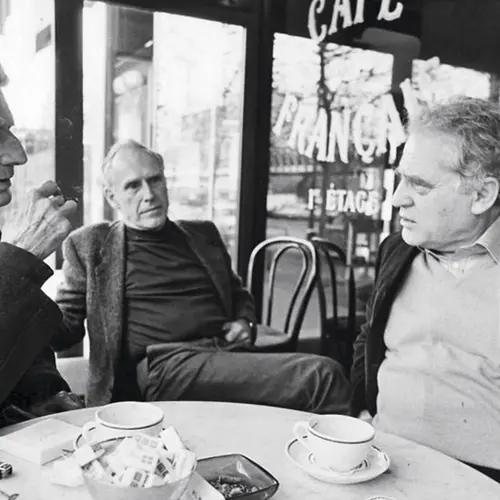

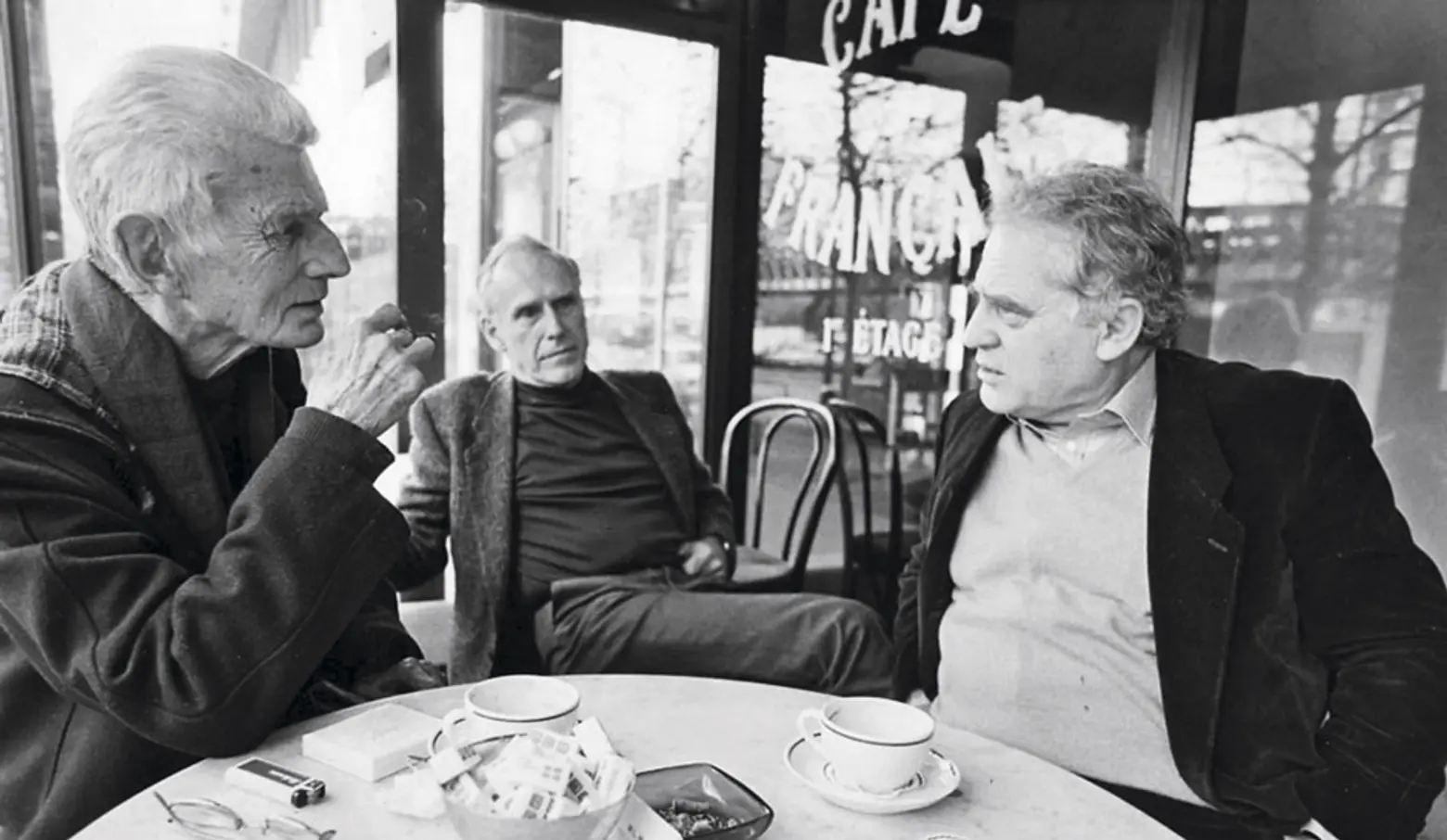

Photo of Barney Rosset (middle) via Wikimedia

3. Barney Rosset

Few people who were not writers themselves affected 20th-century literature more than Barney Rosset. The founder and owner of the Grove Street Press, Rosset made it his life’s mission to share literature which he deemed important but which authorities might have deemed obscene or mainstream American audiences might have overlooked, and to a remarkable degree, he was successful.

He led the successful legal battle to publish Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and the uncensored version of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. In 1964 his right to publish Miller’s work was argued all the way to the Supreme Court and is considered a landmark ruling on First Amendment free speech rights.

Rosset also introduced American audiences to numerous influential writers, including William S. Burroughs, Eugene Ionesco, John Rechy, Jean Genet, Pablo Neruda, Tom Stoppard, and Samuel Beckett. He was a great proponent of the Beat writers, publishing and promoting the works of Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. He published not only sexually explicit but politically explicit writings, including the Autobiography of Malcolm X and Che Guevera’s The Bolivian Diaries, the latter of which resulted in a fragmentation grenade thrown through the window of the Grove Street Press’ Greenwich Village offices. In its early days, the Press operated out of Rosset’s apartment at 59 West 9th Street.

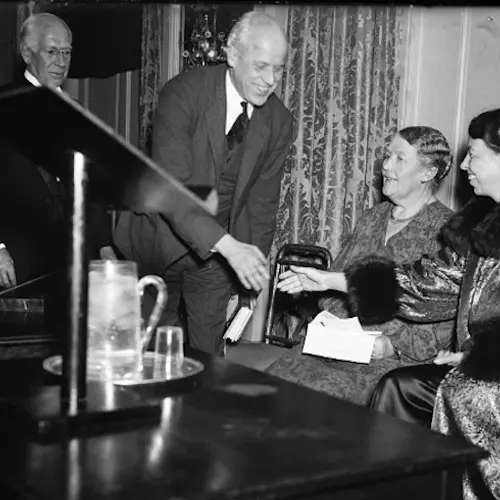

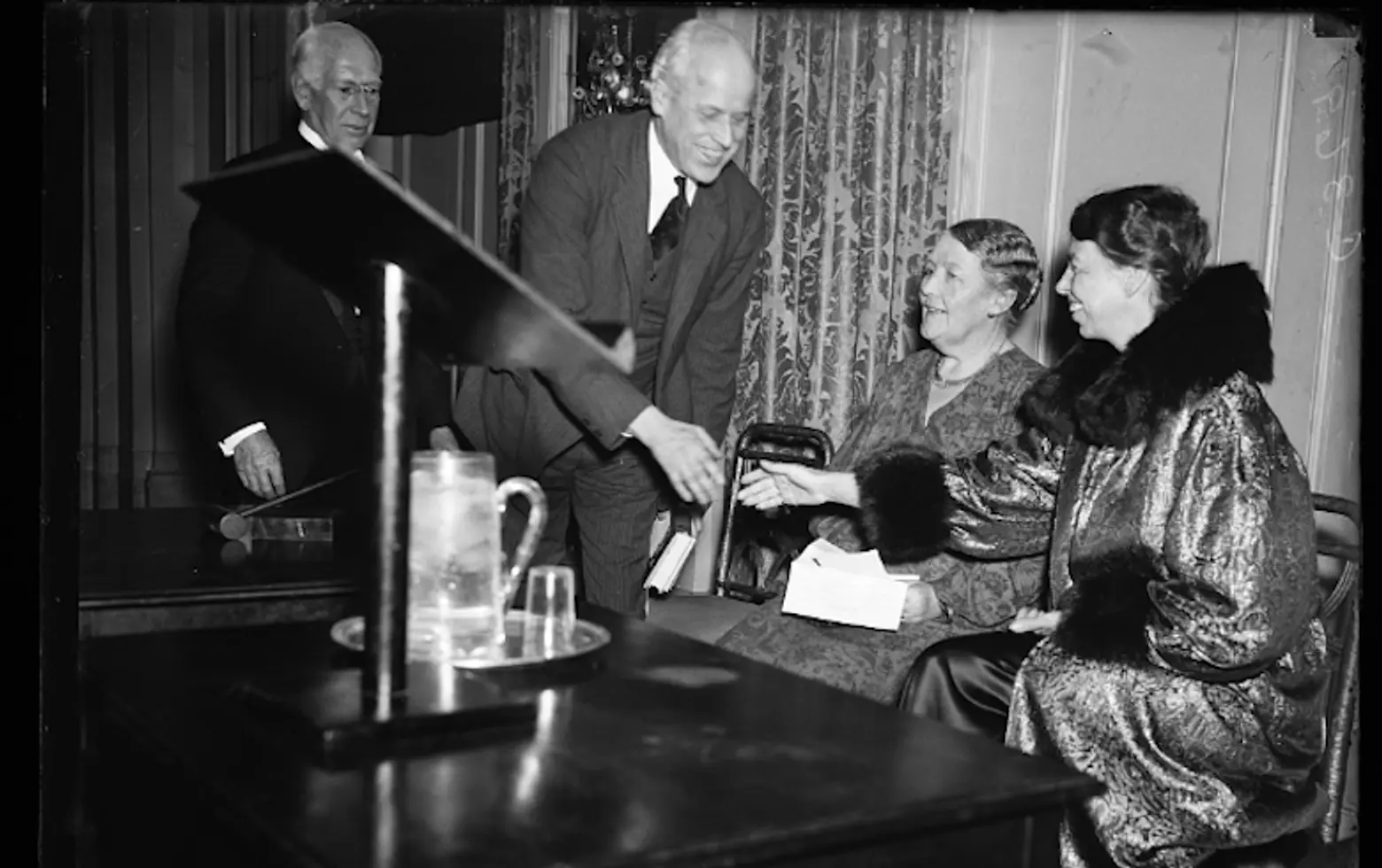

Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch at the National Public Housing Conference via Library of Congress

4. Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch

Simkhovitch was one of the pioneers of the Settlement House movement, established to aid and support recent immigrants to this country. In 1902, she and Jacob Riis, Carl Schurz, and other social reformers joined to found Greenwich House, located at 27 Barrow Street. Simkhovitch and Greenwich House’s work led to the publication of the country’s first tenants manual and the founding of United Neighborhood Houses, which to this day remains an umbrella group for the several dozen settlement houses still operating in New York City.

By focusing on the arts and innovative approaches to education and enrichment, Simkhovitch was able to attract the participation and support of such notable figures as Eleanor Roosevelt, Gertrude Whitney, Daniel Chester French, John Sloan, and Jackson Pollock. During and after her leadership at Greenwich House, the organization accomplished many firsts for Settlement Houses, including establishing a nursery school in 1921, an after-school program in 1942, and a drug-free outpatient counseling center in 1963.

She eventually became the first Vice-Chairman of New York City’s Housing Authority, where she co-authored the National Housing Act of 1937, which established the federal government’s responsibility to provide low-income housing, generating hundreds of thousands of units in the years that followed.

Minetta Street, the center of “Little Africa,” 1925; photo via NYPL

5. Howard Bennett

While far from a household name, nearly every American knows the results of Bennett’s efforts – it was he who spearheaded the successful drive to have Martin Luther King’s birthday designated a national holiday. Bennett was born at a no-longer-extant tenement at 11 Greenwich Avenue – one of the last remnants of the ‘Little Africa’ community located in the center of Greenwich Village in the 19th century.

Bennet was actively involved in African-American civil rights efforts after leaving the military following World War II, participating in many of the great marches and demonstrations led by Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s. However, following King’s assassination in 1968, Bennett made it his life’s mission to see King’s birthday become a national holiday. He faced an uphill battle on many fronts, including tepid support from some African-American leaders in Congress and vigorous opposition from those on the right.

Bennett’s dream came close to reality in 1979 when Congress voted upon the proposed designation, but it fell two votes shy of passage. Sadly Bennett died in 1981 before he could see the full fruits of his labor. The measure was finally enacted in 1983 only after passing Congress with a veto-proof majority, where it was signed by President Reagan, who had opposed the measure.

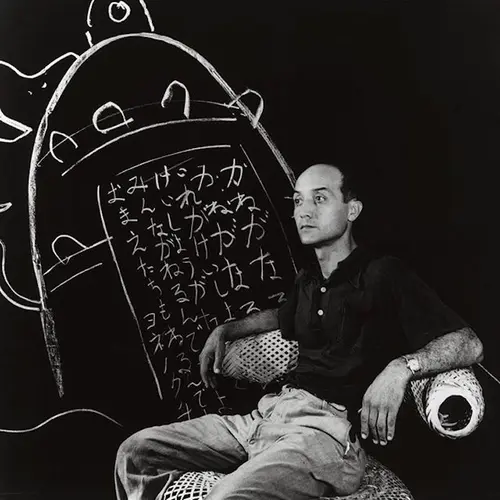

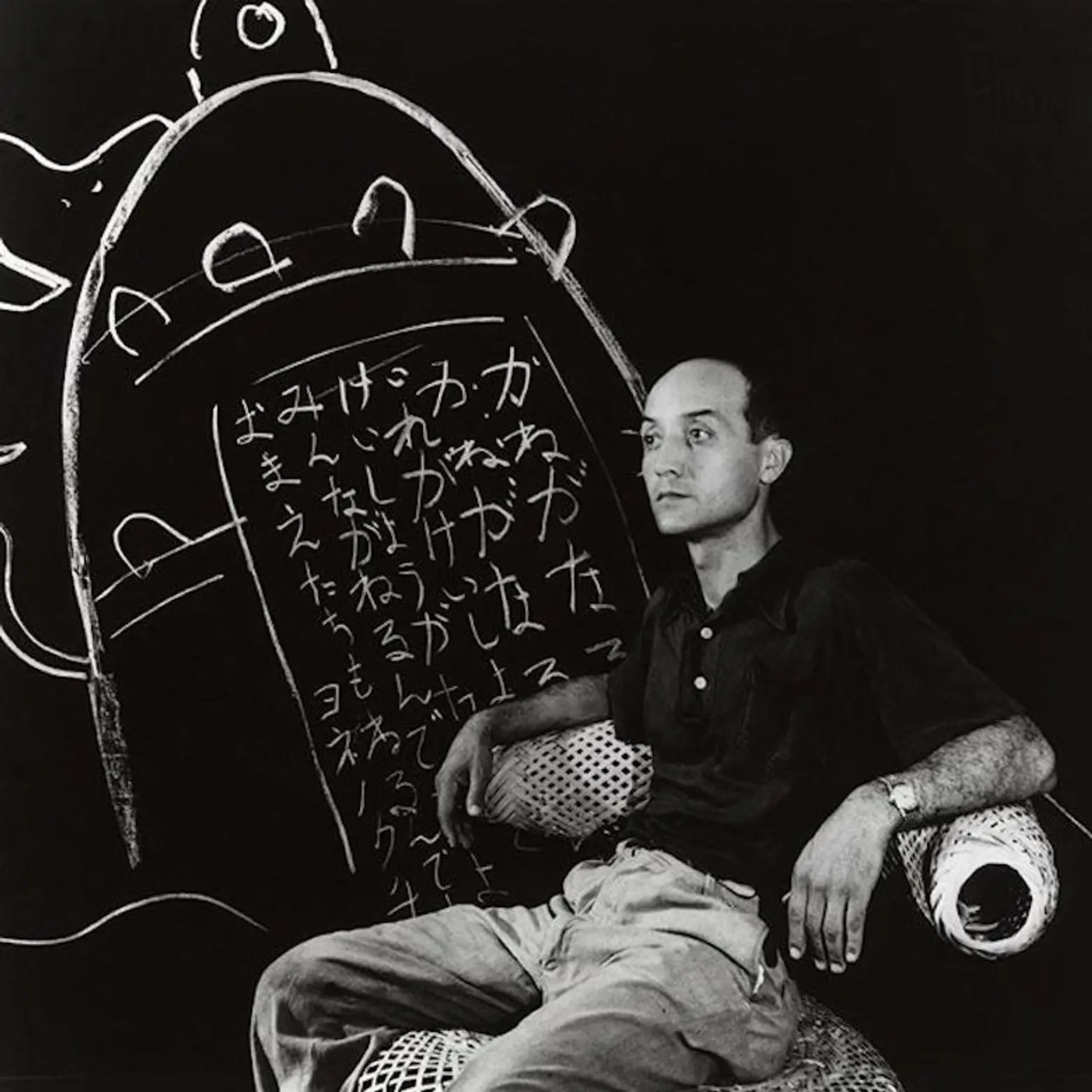

Photo of Isamu Noguchi via Wikimedia

6. Isamu Noguchi

Isamu Noguchi, the son of an Irish-American mother and Japanese father, was one of the 20th century’s most important and critically acclaimed sculptors. He was also an outspoken critic of the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, and though he could have avoided internment himself, was voluntarily interned in a camp for seven months. From 1942 until the late 1940s, Noguchi lived and worked at 33 MacDougal Alley, which was soon after demolished to make way for the high-rise apartment building at 2 Fifth Avenue.

By the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Noguchi was already a well-known and accomplished sculptor. When anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States escalated following the attack, Noguchi formed “Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy” to speak out against the internment of Japanese-Americans, testifying at congressional hearings and lobbying government officials. Despite his and others’ efforts, over one hundred thousand Japanese-Americans were sent to internment camps, though this only applied to those living on the West Coast. Noguchi reached out to John Collier, head of the Office of Indian Affairs, who persuaded him to travel to the Poston Internment Camp located on an Indian Reservation in Arizona to promote art in the community.

He arrived in May 1942, becoming its only voluntary internee. He found the conditions unbearable, including the extreme desert heat. Although he worked on many projects to increase the quality of life for internees at Poston, he found the authorities had no intention of implementing them. He was viewed with suspicion by both internees, who thought him a spy and an outsider, and the authorities, to whom he was a troublesome interloper. Intelligence officers labeled him as a “suspicious person” due to his involvement in activism against internment. After he left the camp, Noguchi received a deportation order. The FBI accused him of espionage and launched a full investigation of Noguchi which ended only through the intervention of the ACLU.

Eleanor Roosevelt with the UN Universal Decorations of Human Rights, in Spanish text (1949); photo via Wikimedia

7. Eleanor Roosevelt

The former first lady spent much of her life after the White House at 29 Washington Square West, where she continued and built upon her prior career as a groundbreaking advocate for change and social reform.

During her time as First Lady, from 1933 to 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt changed the role from the passive hostess to active political leader and became an outspoken politician in her own right. She held press conferences on important issues such as women’s rights and children’s causes and led marches and protests. She stoked controversy but affected change as an advocate for African American civil rights, resigning from the Daughters of the American Revolution when they refused to allow Black singer Marian Anderson to sing at Constitution Hall, famously helping to arrange for her to perform an open-air concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial instead.

She called for an end to racial discrimination in the dispersal of federal funds and decried the poor conditions at African American schools and facilities in her weekly column. She frequently invited African American guests to the White House, which was virtually unheard of at the time and much reviled in some quarters. She later became a U.S. delegate to the United Nations, chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights, and is widely regarded as one of the most renowned civil rights activists of the 20th Century.

During the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925; Hays is seen on far right; photo via Smithsonian Institute on Flickr

8. Arthur Garfield Hays

Hays, a lawyer and civil liberties advocate, co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1920. Previously, Hays had gained prominence during World War I by representing German-Americans who were discriminated against as enemies in the war. He participated in landmark cases including the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925 (questioning a teacher’s right to teach evolution in the classroom), the defense of due process for anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti, and the Scottsboro trials – a series of trials involving nine young Black men in Alabama, who were accused of raping two white women in 1931.

In the case Brown v. Board of Education, Hays filed an amicus brief on behalf of the ACLU in support of the plaintiffs. Hays even championed civil liberties overseas. In 1933, he traveled to Berlin to attend the Reichstag trial, where then-Chancellor Adolf Hitler was advocating for the suspension of the civil liberties of accused arsonists, who had allegedly set fire to the German parliament. Hays lived much of his adult life at 24 East 10th Street. Many accounts mention top leaders of the NAACP, the ACLU, and other organizations coming together at the house.

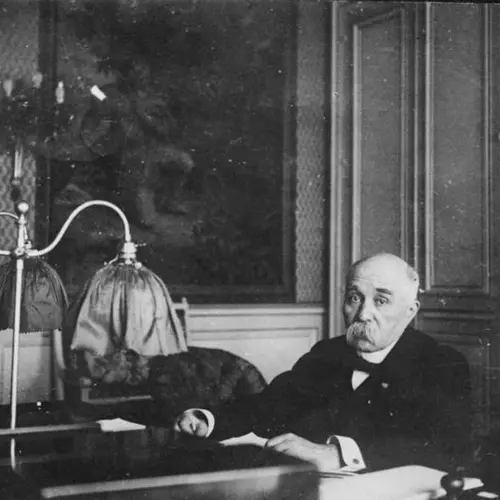

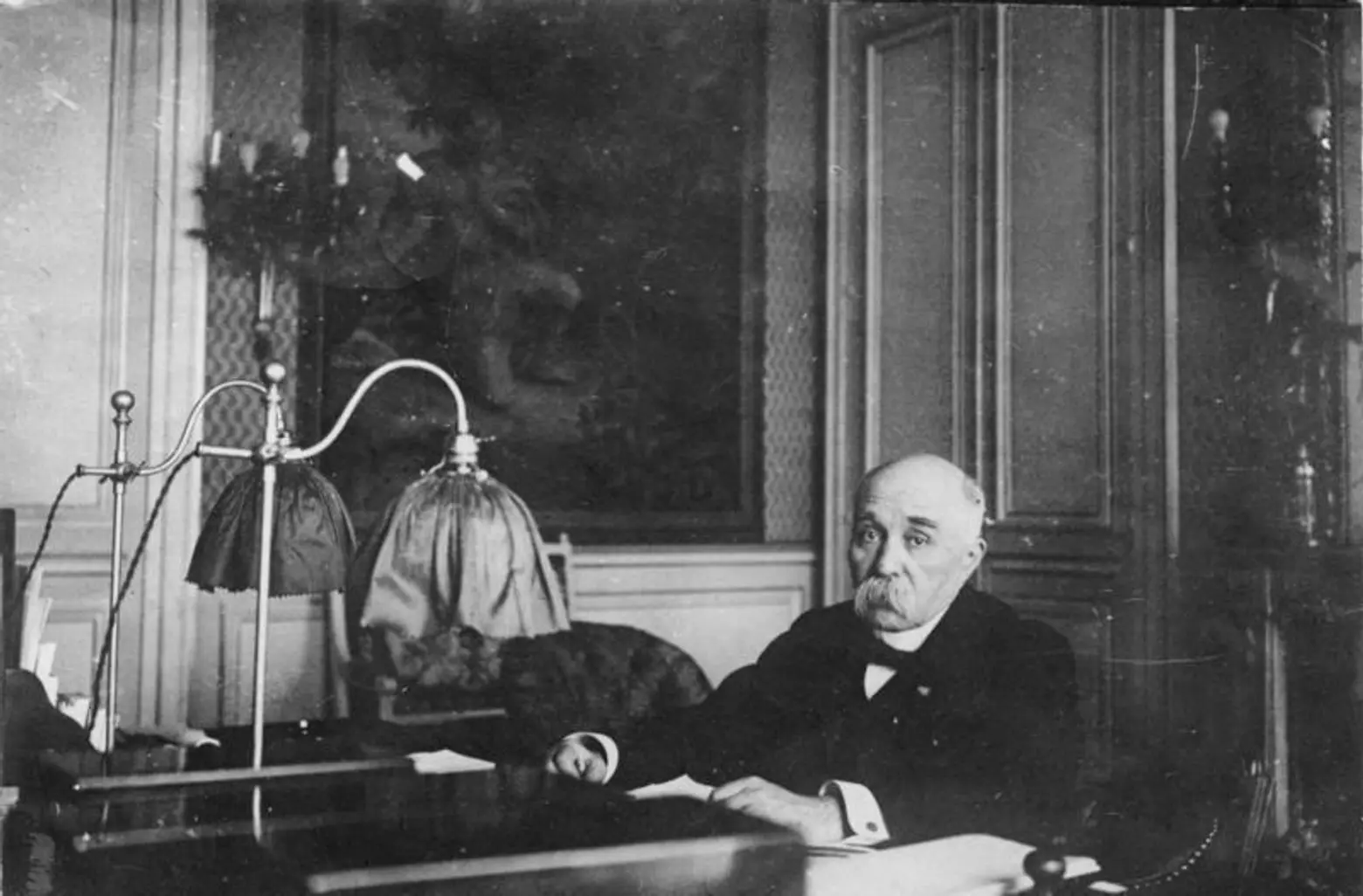

Photo of Georges Clemenceau via Wikimedia

9. Georges Clemenceau

‘J’Accuse!,’ the renowned refrain against anti-Semitism, or more generally against the powerful in the miscarriage of justice, is rarely associated with Greenwich Village. Yet without a onetime resident of the neighborhood, it would never have come to be. Georges Clemenceau was a French politician, physician, and journalist who served as the Prime Minister of France during World War I. Before that, however, he was known for his outspoken opposition to the anti-Semitic persecution of Alfred Dreyfus in France in the late 19th century.

From 1865-1869, Clemenceau lived in a now-demolished building at 212 West 12th Street in Greenwich Village. As a young man, he was a political activist and writer, jailed for his leftist political articles. During a time when the regime of Napoleon III was sending dissidents to Devil’s Island, a prison in French Guiana, he escaped to the United States. Though he was a trained medical practitioner, he spent much of his time on political journalism. When he returned to Paris after the fall of the Second French Empire, he took on a career in politics.

In 1894, he became involved in the Dreyfus Affair. Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian and Jewish descent, had been sentenced to life in prison for allegedly sharing military secrets with the German Embassy in Paris. The affair came to be seen as a universal symbol of injustice and pervasive European anti-Semitism in the late 19th century. During this period the writer Emile Zola was an outspoken opponent of anti-Semitic nationalist campaigns. Clemenceau was an active supporter of Zola and wrote hundreds of articles defending Dreyfus during the affair. Zola’s fiery open letter to the French President accusing the government of anti-Semitism and of unlawfully jailing Dreyfus, titled ‘J’Accuse!,’ was published on the front page of Georges Clemenceau’s liberal Paris Daily L’Aurore.

1937 photo of Hank Greenberg, far right, via Library of Congress

10. Hank Greenberg

Baseball Hall of Famer and two-time MVP Hank Greenberg, who was born in 1911 to immigrant parents at 16 Barrow Street (right across the street from Greenwich House, coincidentally) just wanted to play baseball. But he became an unlikely symbol for religious pluralism and civil rights in America in 1934 when he refused to play in a game scheduled for Yom Kippur, even as his team, the Detroit Tigers, were in a race for the pennant.

Though not religious himself, Greenberg was one of the first prominent Jews in major league baseball, and often had anti-Semitic taunts and jeers hurled at him as a result. Nevertheless, he helped lead his team to two World Series victories and was the American League home run leader for four seasons, earning him the nicknames “Hammerin’ Hank” and “The Hebrew Hammer.” But his decision not to play on Yom Kippur in 1934, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, earned the scorn of some fans and commentators but the begrudging respect of others. In 1940 Greenberg became the first major league player to register for the peacetime draft, and eventually served nearly four years in the army.

When Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier to become the first African-American to play major league baseball, Greenberg became the first player from an opposing team to publicly welcome Robinson and offer support. The two became friends, and Greenberg offered advice on dealing with the public taunts and condemned the racist provocations hurled at Robinson. When he became manager of the Cleveland Indians after his retirement from play in 1947 (Robinson’s first year in the major leagues), Greenberg actively recruited more African American players than any other team, making the Indians for a long time major league’s team with the broadest representation of African-American players.

Pete Seeger, singing while playing banjo in 1955, via Library of Congress

11. Pete Seeger

The folk singer and social activist spent much of his most prolific years in Greenwich Village, living among other places at what was known as the ‘Almanac House’ at 130 West 10th Street, which still stands. The writer of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” “If I Had A Hammer,” and “Turn, Turn, Turn,” he was also one of the first musicians to popularize the spiritual “We Shall Overcome.” Seeger combined music and political messaging to become a passionate spokesperson for civil rights, environmentalism, the peace movement, and fighting right-wing oppression, inscribing upon his guitar and banjo “This Machine Kills Fascists.”

Seeger was one of the pioneers of the folk revival of the 1940s and 50s, which gained widespread popularity in the 1960s, becoming one of the most popular singers in America. He supported the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War and advocated for racial integration. He and his fellow members of the Almanac Singers lived in the house at 130 West 10th Street in 1941, holding hootenannies to raise funds for the rent. Black and white musicians and audiences were welcomed, and Seeger had a particularly close relationship with Blues musician Huddy “Leadbelly” Ledbetter. With the Red Scare of the 1950s, Seeger’s left-wing leanings came under scrutiny and suspicion, but he enjoyed a revival of popularity in the 1960s.

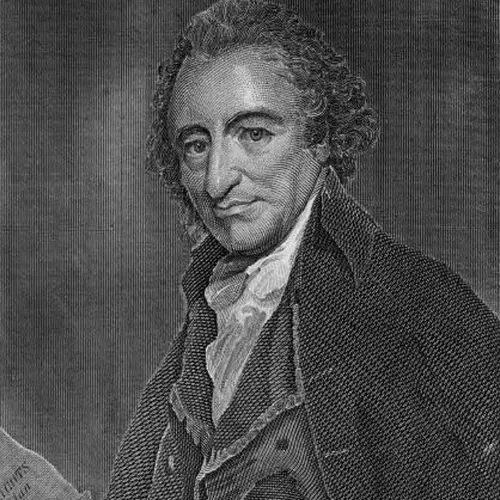

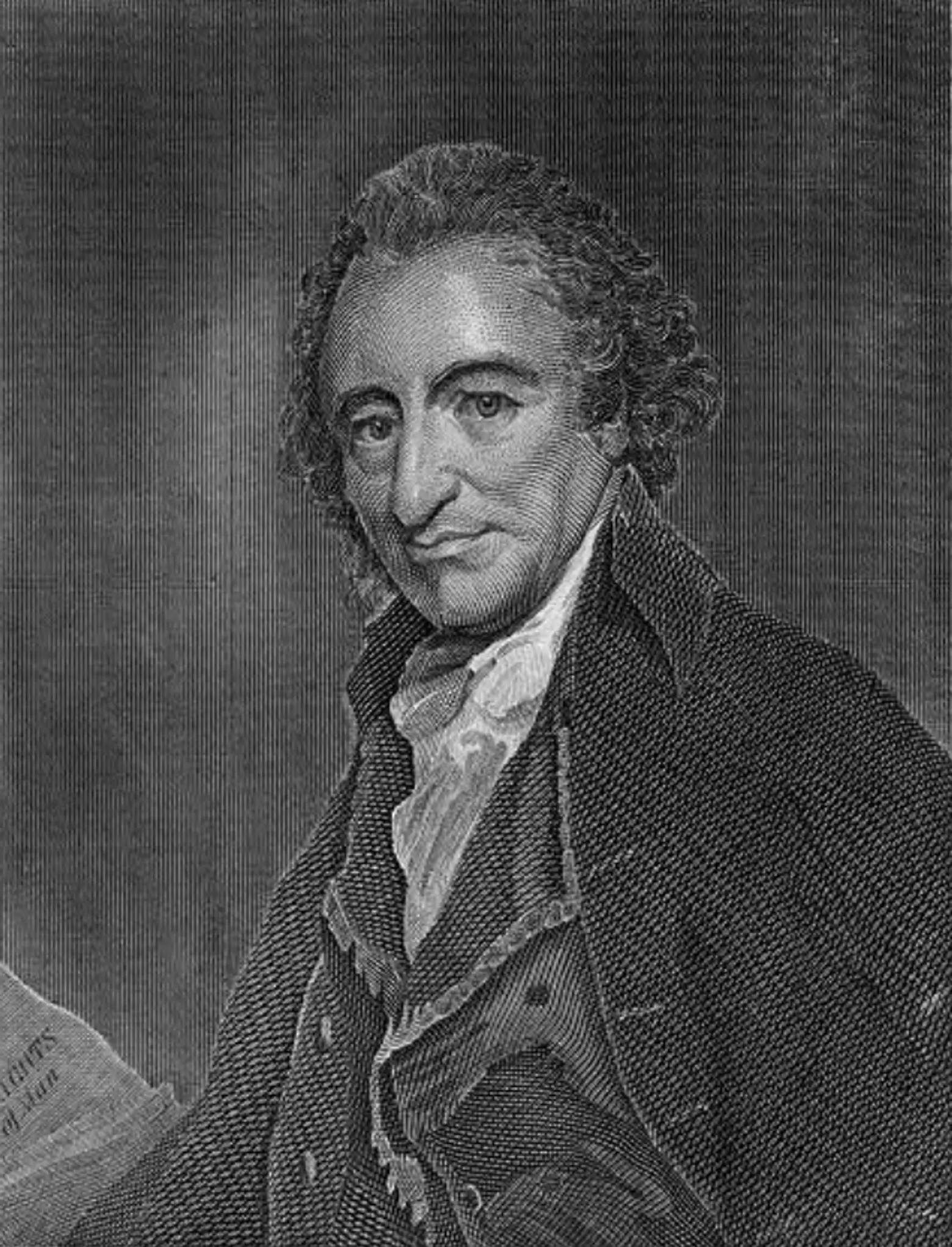

Painting of Thomas Paine via Library of Congress

12. Thomas Paine

Paine was a political theorist, revolutionary, and writer, whose works helped inspire the American Revolution, the French Revolution, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. Considered one of America’s Founding Fathers, his 1776 pamphlet Common Sense was so widely read it is said that proportionally it is the all-time best-selling American piece of literature. Common Sense was so influential that John Adams said, “Without the pen of the author of Common Sense, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain.”

In the 1790s Paine lived in France and was deeply involved in the French Revolution. There he wrote The Rights of Man, which argued not just in support of the French Revolution, but for the intrinsic human rights of men. In later writings Paine also argued for a guaranteed minimum income and against institutionalized religion, preferring instead reason and free thought. He was also a fervent opponent of slavery.

Paine returned to the United States in 1802, and lived first in the house at 309 Bleecker Street, and then at 59 Grove Street, both no longer extant. Paine inspired considerable controversy in the United States, where he was attacked as a radical, a foreigner, and an atheist. He died poor and nearly friendless. Supporters petitioned to have nearby Barrow Street renamed ‘Reason Street’ in his honor shortly after his death.

But contempt for Paine was so widespread that the street came to be called derisively ‘Raisin Street.’ In 1828 city fathers renamed it Barrow Street, which it remains today. While the homes in which Paine lived and the street renaming in his honor were destroyed, Paine’s memory lives on at the present-day 59 Grove Street. The bar ‘Marie’s Crisis’ which has occupied the ground floor for well over a century, was so named in honor of Paine’s The American Crisis, and since 1923 there has been a plaque identifying this as the site of Paine’s home.

RELATED:

- 20 transformative women of Greenwich Village

- 13 places in Greenwich Village where the course of history was changed

- Black history in Greenwich Village: 15 sites related to pioneering African-Americans

+++

For updates and more details about the Greenwich Village Historic District 50th anniversary and a full roster of events, click here >>

For updates and more details about the Greenwich Village Historic District 50th anniversary and a full roster of events, click here >>

+++

This post comes from Village Preservation. Since 1980, Village Preservation has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid