My 1,300sqft: Artist Rob Wynne’s glass installations mix with eclectic decor in his Soho loft

Our series “My sqft” checks out the homes of New Yorkers across all the boroughs. Our latest interior adventure brings us to artist Rob Wynne’s Soho loft. Want to see your home featured here? Get in touch!

“If you have something to say, you figure out what material will help you fulfill that destiny,” said artist Rob Wynne, referencing the various mediums in which he works, from hand-embroidered paintings to sculpture to molten glass. It’s this “alchemy” that is currently being explored through his exhibit “FLOAT” at the Brooklyn Museum, a show of 16 works that “seemingly floating within the American Art galleries.” But Wynne’s talent is perhaps on display nowhere more so that his home and studio in Soho.

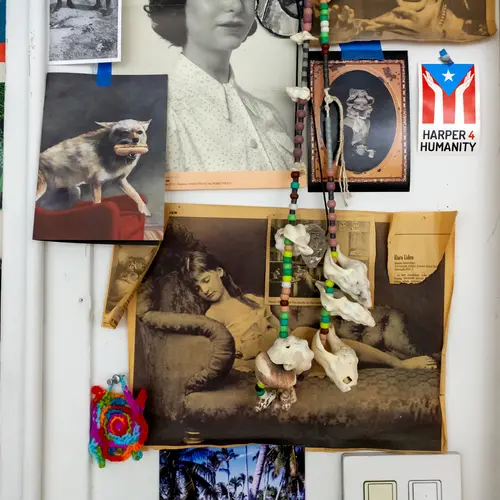

Wynne moved to the artist’s loft in the ’70s, and what has resulted is an organic and eclectic mix of decor and furniture from decades of travel, meeting fellow NYC artists, and finding inspiration through various disciplines. 6sqft recently visited Rob at his home and explored his collections of curiosities. We also got an up-close look at the process behind his large-scale mirrored glass installations, as well as many of his other incredible works.

Most of the living room chairs are from flea markets, even as far back as the ’70s.

Most of the living room chairs are from flea markets, even as far back as the ’70s.

What brought you to Soho?

I was born at Mount Sinai and lived on the Upper West Side until I was eight. I was taken by my family to Long Island, unfortunately, and I was able to leave there when I was 18 to go to Pratt in Brooklyn. And after graduating in 1970, I first moved to Beach Street, in Tribeca. Then, in 1975, I ended up at a place on Canal and West Broadway and I’ve been here ever since.

In those [early] years, the neighborhood was light manufacturing, so it was not zoned for living. It was illegal to live here. My college roommate lived upstairs [from this loft] and alerted me to the fact that it was for rent. I came in. We were the first renters on this particular floor. It originally was being used as a manufacturer of games of chance, roulette wheels and that type of thing. So there was nothing here. It was just loft space. There were no ceilings, just a pull-chain toilet in the back. It was empty, and then over the years I fixed things up and renovated.

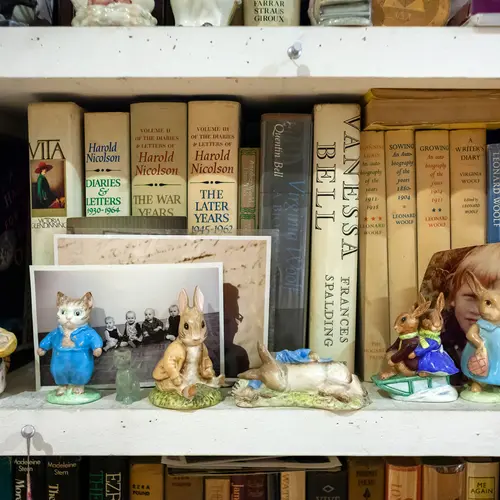

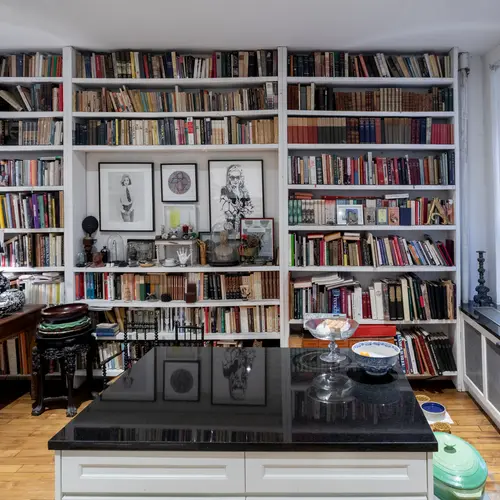

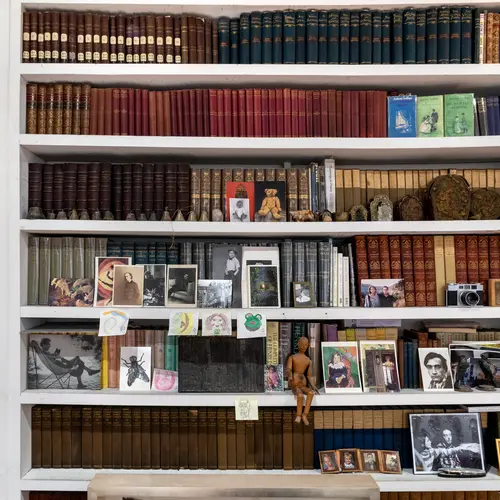

The books behind the desk belong to Rob’s partner, who is a writer and translator. They’re 19th-century French and English novels.

The books behind the desk belong to Rob’s partner, who is a writer and translator. They’re 19th-century French and English novels.

How have you seen the demographics change since then?

Those days [of artists] are gone pretty much. Basically, there was a conversion in the late ’70s, and they became AIR (Artist in Residence) buildings, which you had to prove you were an artist in order to live here legally. How you would do that is you would bring slides of your work and some kind of proof that you’d had a show somewhere and show it to the Commissioner of Cultural Affairs, who in those years was Bess Myerson. She would stamp the thing and say, “You’re an artist,” and that would legally mean you could live here. I have friends and colleagues from those years who are still here, but obviously it’s changed a lot.

The Brillo Box isn’t a Warhol. It’s by artist Mike Bidlo, a prominent appropriation artist from the ’80s.

The Brillo Box isn’t a Warhol. It’s by artist Mike Bidlo, a prominent appropriation artist from the ’80s.

How did you go about designing the space?

It’s accumulation style. I didn’t make a conscious effort to design where I live. I share the space with someone who’s a bibliophile, so there are a lot of books and things that aren’t necessarily my choice, but there’s a mixture of styles. But the fabrics are from traveling the world, finding this here or there, just covering horrible things underneath it type of thing.

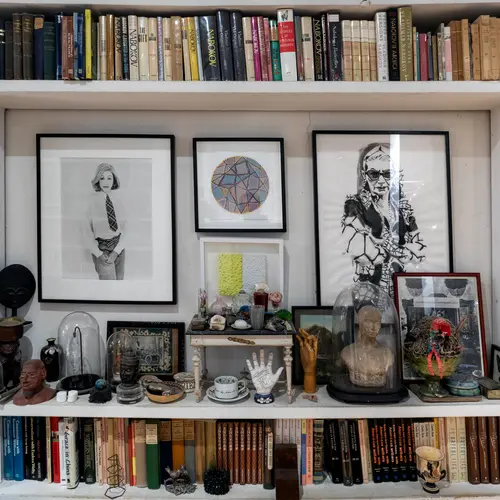

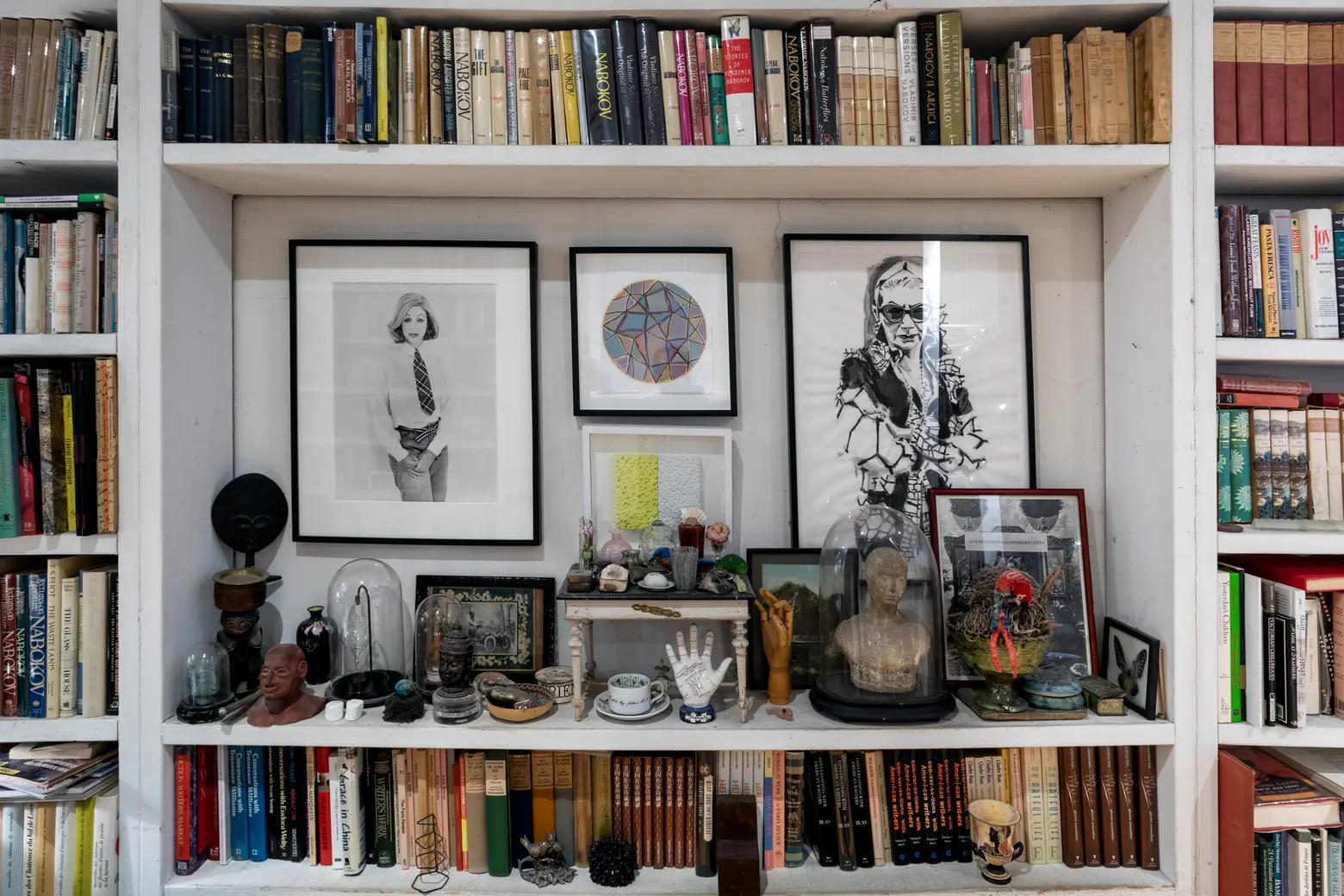

Rob has an affinity for domes.

Rob has an affinity for domes.

Do you have a particularly prized possession?

I have a collection of artworks that I’ve traded with artist friends. Those are amongst my favorite things. I have a beautiful Kiki Smith. I have a Jack Pierce, Laurie Simmons, Pat Steir – friends of mine that I grew up with. Usually in exchanges.

This glass piece is titled “Vertigo.”

This glass piece is titled “Vertigo.”

What about your own work. How do you decide which of your pieces to display?

I’m always playing with my work because it’s an ongoing process of how I make it. So I just put things up depending on how I feel they’ll interact and have a dialogue with the other pieces that I’m working on or thinking of making.

This one is “New Silver Horizon.”

This one is “New Silver Horizon.”

Tell us a bit more about your work. The poured glass pieces are incredible.

I’m not a trained glass artist, so I don’t come to the use of it in the traditional sense. It was really by chance. It was in the early ‘90s, and I was working on an installation for a show called “Sleepwalking,” and I wanted to have a pair of glass feet. So I made a plaster cast of my feet and took the mold to Urban Glass in downtown Brooklyn. With the assistance of some technicians, we forced the molting glass into the mold and out came a very realistic [set of feet]. While I was there, I was fascinated with the all-chemical-like nature and the choreographed way that you kind of picked up the different parts of tools and processes that were necessary to get to the end result.

In those years, a lot of my work was text-based and referencing language. And a bell went off in my head and I thought, “Why couldn’t I just draw with this material?” So they suited me up, gave me a ladle, and I took it out of the furnace. It was very hot and unsteady, so it slipped out of my hands and made this cosmic splat on the floor. And they said, “Uh, don’t worry about it. We can try again.” But I really liked it. In fact, we saved that first piece and lifted it up off the floor. From there, I started experimenting with pouring the material and not casting in the traditional sense. Since there were no molds, you could really use it organically. It just deepened and I kept referencing it.

But typically, I use a lot of different materials. The smoke drawings are a result of the casting process. When something is poured from the furnace, in order to for it to cool, it has to be moved onto wood. The wood is then carried to an oven that’s calibrated to reduce temperature so the glass won’t break. It cools over a period of days, but while the piece is on the wood it produces smoke, which is really the byproduct of charcoal. So a lot of my work is processed, infused–the beauty is in the doing. And out of the doing comes all these sparks metaphorically and actually, that then bring different ideas. If you have something to say, you figure out what material will help you fulfill that destiny.

For the text-based pieces, how do you decide what words you’re going to incorporate?

I read a lot of poetry and I particularly like short, 17th- and 18th-century Japanese Haiku poetry, which distills observation in a very poignant way. So I appropriate some texts from that. A lot of times I’ll overhear things that fascinate me. People say just unbelievably things, and I keep a notebook. Sometimes I think of a word and then I look up synonyms for it and see how they bounce around off of that. Sometimes they’re geared toward a specific show that I’m doing. So if I’m forming an exhibition, I’ll think about the parameters of what the feeling is of the exhibition and try to allocate certain words or phrases that reflect what the gist of it is.

I like the word “yes” very much because I’m interested in permission. I’ve probably cast it once, but I’ve used it aversively in other things. I have a ceramic sculpture in the back which has it on it, and I made a ring that says “yes,” and I’ve made an embroidered pigment piece which says “yes” on the lips. I, like probably a lot of people before me, was told “no” a lot, and I didn’t care for that. I like “yes.” It seems positive and uplifting.

The poured glass pieces are made up of so many small components. How do you afix them?

It’s laid out on paper [on the floor]. That will become a template, which is a map that will then have all the information necessary to transfer it to the wall, which is very simple. Each component is assigned a number; the number is written on the back of the component and also on the template. It was particularly important in the “FLOAT” exhibition [at the Brooklyn Museum] because the piece “Extra Life” has approximately 1,200 unique parts. It’s not dissimilar to the way Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings are transported and made after his death. There’s still a way to follow how you do it. So my pieces have templates which, if you follow the protocol, it shows you exactly where each piece goes.

How long do they take to create?

It’s very hard to answer that with any real precision because it’s organically developed. Even the smallest dot is handmade. It probably only takes seconds to make one dot, but then the whole process is over a period of time because I will make, maybe, 1,500 dots in a day. As you make them, they’re moved into the oven and then they cool for two or three days. When they come out of the casting, then they have to be drilled, which my assistants do.

Then they have to be silvered. I use to do the silvering myself, but it’s very toxic. Even though it’s no longer mercury, which is illegal, if you don’t have the right ventilation it’s really a nightmare. So they go out to a re-silvering place that restores mirrors in Ridgewood. And there the silvering solution is applied. These pieces are organically poured, and then this real mirror, which is cut out and also drilled in, those are put together as one piece.

Realistically, it probably takes about six months for something of this scale, from the first drawing of it to when it’s finally done. If you could speed up all the process, it would be faster, but each piece is handmade, hand-finished, hand-drilled, hand-silvered, hand-put together. The template is made, numbered, put on the wall. So it takes months.

How has the show at the Brooklyn Museum been?

It has been a particularly nice experience. Since I lived in Brooklyn for many years when I went to Pratt, that was really the art temple for me as a young art student. So I spun full circle to be able to go back there and interact with that collection and find so many interesting, little-known works, particularly by people whom I never heard of. They have a very, very intensive and deep commitment to women artists, so to start learning about them through the curators there and interact with them was very interesting. Revelatory, actually.

Where are some places where you like to go to see others’ artwork?

I think I’m pretty catholic in my taste. I’m curious about pretty much everything, so I take advantage of a lot of the opportunities. I travel a lot, so when I’m in other countries or states I think it’s important for me, as an artist, to learn from looking at art. That’s how I educate myself and can think and reflect back on how I feel about what I’m doing. So I look at art in all galleries and museums. I’m also pretty absorbed with keeping up with artist friends who are having performances if it’s either poetry, dance, or visual arts. So I go to all my friends’ openings and venues, which is considerable.

What does a typical work day look like for you?

I get up around 7:30, and I go to the gym in the morning. I’m very regimented. I pretty much work in the afternoon, from probably noon to 6:00. I don’t work way late into the night. I did when I was younger, but now I try to sleep. On the weekends, I have my long-time studio manager come in. He lives upstate, and he works with me to organize things. If I’m not here, I’m working out in Gowanus and Red Hook where I use Brooklyn Glass‘ studios and a store where I do casting. I’m also making some prints at a venue in Long Island City.

The kitchen was recently upgraded from its loft incarnation to have modern updates such as a dishwasher.

The kitchen was recently upgraded from its loft incarnation to have modern updates such as a dishwasher.

Do you ever think about moving?

I never really think of moving. I mean, as I say, I travel a fair amount. I used to spend more time in Europe. I have one of my galleries in Paris. But I don’t think I’ll ever leave here. Not at this point.

+++

FLOAT is on view until March 2nd. Find more details here >>

This interview has been edited for clarity.

RELATED:

- Where I Work: Artist Nancy Pantirer shows us around her imaginative Tribeca loft

- Where I Work: Artistic duo Strosberg Mandel show off their Soho studio and glam portraits

- My 1,400sqft: Painter Stephen Hall Brings Us Into His Greenwich Village Loft and Studio

- My 2,200sqft: Rug designer Amy Helfand shows us around her organic live/work home in Red Hook

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.