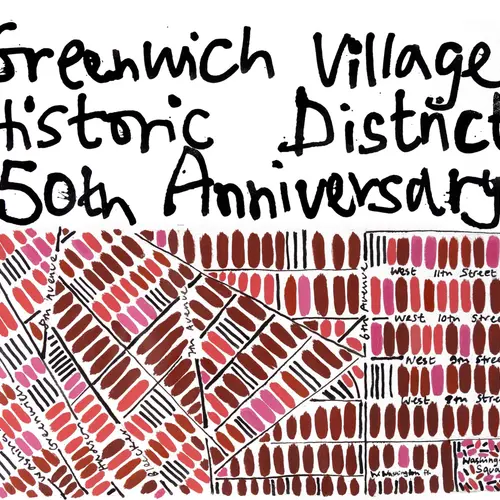

The 10 most charming spots in the Greenwich Village Historic District

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the designation of the Greenwich Village Historic District on April 29, 1969. One of the city’s oldest and still largest historic districts, it’s a unique treasure trove of rich history, pioneering culture, and charming architecture. GVSHP will be spending 2019 marking this anniversary with events, lectures, and new interactive online resources, including a celebration and district-wide weekend-long “Open House” starting on Saturday, April 13th in Washington Square. This is the first in a series of posts about the unique qualities of the Greenwich Village Historic District marking its golden anniversary.

The Greenwich Village Historic District literally oozes with charm; so much so, it’s virtually impossible to come up with a top-10 list. But with no insult to sites not included, here is one run at the 10 most charming sites you’ll find in this extraordinarily quaint historic quarter–from good-old classics like the famous stretch of brick rowhouses on Washington Square North to more quirky findings like the “Goodnight Moon” house.

Washington Square North, via Wiki Commons

Washington Square North, via Wiki Commons

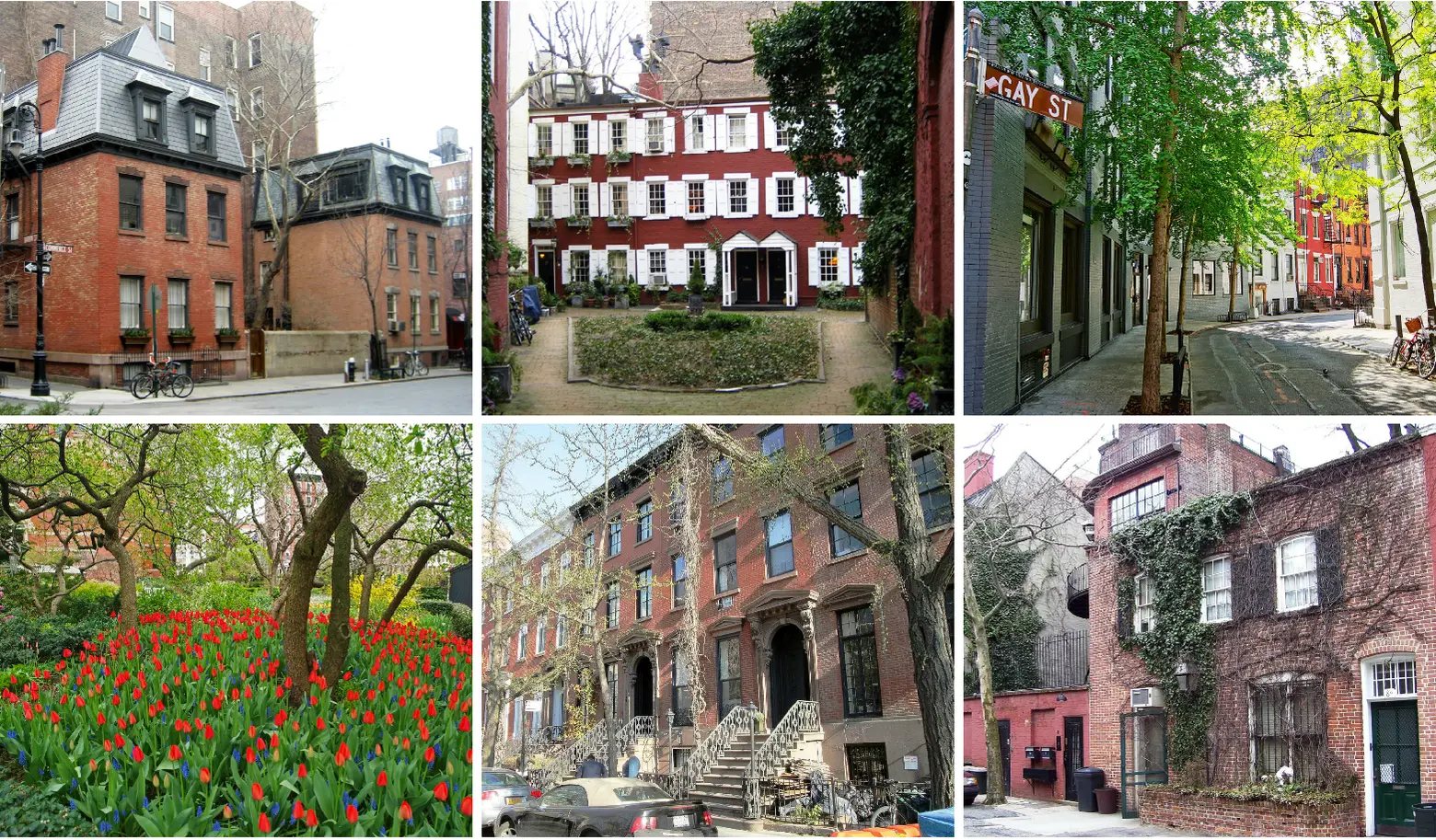

San Francisco has its painted ladies on Alamo Square, and New York has these lyrical red brick houses on Washington Square. Built in 1832 to house New York’s wealthiest families, they were immortalized in Henry James’ “Washington Square” and Edith Wharton’s “The Age Innocence.” Though the houses appear remarkably intact today, all is not as they seem. Numbers 7 through 13 were actually demolished behind their facades (which were also altered) in 1939 when they were combined and turned into an apartment building. None are still houses, as most are owned and occupied by NYU. Edward Hopper’s home and studio was located in 3 Washington Square North from 1913 until his death in 1967, in one of those NYU-owned buildings. “The Row” as it is often called is considered the finest collection of Greek Revival houses in New York, nearly all of which maintain their original iron fences in front and stone Greek Revival entryways and stoops.

2. MacDougal Alley and Washington Mews

Washington Mews, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

Washington Mews, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

These two charming back alleys are lined with quaint structures that abut the houses of Washington Square North and what were once the grand houses of 8th Street. While popular lore says these were built as stables for the fine manses they bordered, as on Washington Square North, not all is what it seems here. While some of these structures were indeed built as stables, others were actually automobile garages, and some were built as apartments from the beginning, merely mimicking the “stable” look of their neighbors.

MacDougal Alley, via Wiki Commons

MacDougal Alley, via Wiki Commons

Washington Mews, located between Fifth Avenue and University Place, is gated at both ends, though the gates are generally left open to allow public access. Nearly all of its buildings are owned or occupied by NYU. MacDougal Alley, on the other hand, located between 5th Avenue and MacDougal Street, is almost always locked at its western end, and the eastern end is permanently blocked by the mass of the large white-brick apartment building at 2 Fifth Avenue. Some of its buildings are in fact residences, while others are extensions of the New York Studio School on 8th Street or the NYU-occupied houses on Washington Square.

3. Jefferson Market Library and Garden

Jefferson Market in 1893 (L) via Wiki Commons and today (R) via Wiki Commons

Jefferson Market in 1893 (L) via Wiki Commons and today (R) via Wiki Commons

The Jefferson Market Library, constructed in 1874-77, was “one of the ten most beautiful buildings in America,” according to a poll of architects conducted in 1885. The Ruskinian Gothic structure, originally a courthouse, is considered one of the finest examples of High Victorian architecture in America. It was designed by Frederick Clarke Withers and Calvert Vaux, the latter the co-designer of Central Park. When built, the courthouse was part of a complex of buildings that included a prison and a market, which occupied the remainder of the trapezoidal block upon which it is located.

The building’s quirky, eccentric design has long been beloved by Villagers. So much so that they rallied mightily in the 1950s and ’60s to save the building from demolition and have it repurposed as a library, one of the signature preservation victories in New York after the tragic loss of the original Penn Station.

While the building’s architecture may have been beloved, the activities associated with it were not always so well-regarded. For decades it functioned as the courthouse for a district that included the city’s most crime-ridden neighborhood, the Tenderloin. Its clocktower was used as a fire watch lookout, and its bells regularly rang to warn of nearby conflagrations. After World War II, it was converted to a police academy, and for years after that, it was left empty and used only by pigeons and rats.

A 1938 photo showing the Women’s House of Detention south of the Jefferson Market Courthouse, via NYPL

A 1938 photo showing the Women’s House of Detention south of the Jefferson Market Courthouse, via NYPL

But Villagers saved their true disdain for the building which occupied the remainder of the block adjacent to the courthouse beginning in 1929, the Women’s House of Detention. An Art Deco behemoth intended to embody a more enlightened approach to incarceration, it soon became known for its horrible conditions, the abuse suffered by detainees, and the loud and sometimes vulgar interactions between prisoners and passersby or visitors on the street outside (the jail had operable windows).

Jefferson Market Garden, via Flickr cc

Jefferson Market Garden, via Flickr cc

In 1973 the “House of D,” as it was sometimes called, was demolished to make way for the bucolic and pastoral Jefferson Market Garden, a stunningly green oasis footsteps from the hubbub of Sixth Avenue. Its verdant plantings are maintained by a volunteer community group, and while fenced off, the grounds are regularly open to the public for its enjoyment.

4. Gay Street

Gay Street via Wiki Commons

Gay Street via Wiki Commons

Tiny one block long Gay Street attracts as many visitors for its delightfully intimate scale and architecture as it does for its curiosity-inducing name. Laid out in the early 19th century, the diminutive crooked street features federal-style houses on its west side built in the 1820s, and Greek Revival-style houses on its east side built in the 1830s, after the street was widened around 1830 and the houses on the east side were demolished. But it’s not just these quaint early 19th century houses which make the street so beloved. The converted factories at its northern end, and the setback wedding cake top of One Christopher Street which hovers over the bend in the street when viewed from the south, all add to the street’s picturesque and romantic feel. While the street is located just feet from the Stonewall Inn, the birthplace of the modern LGBT rights movement, the street’s name is merely a serendipitous coincidence.

5. Grove Court

Grove Court via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

Grove Court via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

Perhaps the most photographed site in Greenwich Village and its historic district is the delightfully surprising Grove Court. Like many streets in the Village, Grove Street east of Hudson Street bends, thus leaving a gap between the houses at numbers 10 and 12, with an unusually deep opening behind them.

Filling that space is Grove Court, a collection of tiny houses behind a private gate and triangular courtyard. Built in 1852-54 as workingmen’s cottages on the rear yards of the 1820s Grove Street houses in front, these are now among the most sought-after residences in New York – at least for those who are willing to live in less than 1,000 square feet. In the 1920s, they were renovated and began to be marketed to artists and those who wished to live among artists in Greenwich Village.

6. “The twins” – 39 and 41 Commerce Street

39 and 41 Commerce Street, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

39 and 41 Commerce Street, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

The twin houses at 39 and 41 Commerce Street are, like many sites on the list, the subject of considerable lore, not all of it true. Originally built in 1831-32 by milkman Peter Huyler, the houses are often reputed to have been built for sisters who refused to speak to one another, and insisted upon a wide yard separating their homes. In fact, in the early 1830s when this area was first being developed, a yard or open space around houses was neither uncommon nor necessarily indicative of a family dispute. What is unusual is that unlike many of these other open spaces (such as today’s Grove Court), the yard here was never built upon, for reasons not entirely clear (prior to 1969, that is; the designation of the Greenwich Village Historic District would have of course made approval of the destruction of such an iconic feature of the district nearly impossible).

While the generous yard between the two houses has not changed over the years, in the 1870s they had their mansards roofs we see today added, which along with the yard are probably their most beloved feature. Like much of the Village, 39 and 41 Commerce Street don’t look as though they could possibly exist in New York and are often used as a stand-in for Paris or other European locations on film shoots.

7. Cobble Court/The “Goodnight Moon House,” 121 Charles Street

Google Street View of 121 Charles Street

Google Street View of 121 Charles Street

Speaking of not looking like it belongs, the tiny white clapboard house behind the gate and large yard at the northeast corner of Charles and Greenwich Streets is adored by those who know it and often inspires a double-take by those who don’t. Rumored to be a miraculous remnant of an 18th-century farm once covering the area, the house’s survival here is indeed a miracle, but its story is decidedly different.

Likely built at the beginning of the 19th century, the house was located behind 1335 York Avenue, between 71st and 72nd Street in Yorkville until it was threatened with demolition in the 1960s. The building had operated as a dairy, a restaurant, and of course a residence, but since 1869 had been separated from the street by a front structure and a courtyard paved with cobblestones, from which its name “Cobble Court” is derived. The building was also used as a residence, most notably by Margaret Wise Brown, who wrote the classic “Goodnight Moon” while living there in the 1940s, as well as “Mister Dog,” which features the house.

In 1965 the home was sold to the Archdiocese of New York, which planned to demolish it for a nursing home. But the tenants of the house, Sven and Ingrid Bernhard, who had renovated the historic property, refused to give up their beloved domicile. They went to court and won ownership of the building (though not the land), and were given six months to find a new home for it.

Cobble Court in 1967, via Landmarks Preservation Commission

Cobble Court in 1967, via Landmarks Preservation Commission

With the help of an enterprising architect, some elected officials sympathetic to the preservation battle, and community leaders in Greenwich Village, a new home was found for the house at a lot on the corner of Charles and Greenwich Streets. Transporting the fragile, antique structure on a flatbed truck through the streets of New York and getting it to its destination intact was a virtually unprecedented feat at the time. But the house arrived unharmed and has remained at this location with just minor alterations and additions for more than the last fifty years.

8. 75 ½ Bedford Street/”The narrowest house in the Village”

75 ½ Bedford Street via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

75 ½ Bedford Street via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

75 ½ Bedford Street was built on what was one of those courtyards or alleyways between houses that were once commonplace in this area, but have almost entirely disappeared. The houses to 75 ½’s north and south were built in 1799 and 1836, respectively. By 1873, when this neighborhood was transforming from a genteel middle-class suburb to a teeming immigrant district, the land between the two houses had been sold to Horatio Gomez, who erected the nine-and-a-half-foot wide house we see on the site today. The steeped Dutch gabled roof dates to this era, while the casement windows, associated with artists’ studios, date to a 1920s renovation when the neighborhood was transforming again to attract writers and painters.

One of the first occupants of the reborn house was none other than Pulitzer Prize-winning Village poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, who lived here from 1923-24, just after she published her famous poem “My candle burns at both ends.”

The house is known as the narrowest in the Village and thought by some to be the narrowest in New York City, though there is some dispute about that claim.

9. Where Waverly Place intersects with itself

In this Google Street View, you can see Waverly Place and Waverly Place coming to a fork

In this Google Street View, you can see Waverly Place and Waverly Place coming to a fork

One of the charming quirks about Greenwich Village is its meandering, eccentric street pattern. The confusing and often seemingly erratic pattern emanates from the continued existence of streets laid out prior to the Manhattan Street grid based upon family farms and relationship to the Hudson River waterfront and the imposition of standard gridded streets on top of them in some locations. The renaming or numbering of old streets to try to reconcile the two further adds to the confusion, by for instance resulting in West Fourth Street at some points running north of West 12th Street.

But perhaps no idiosyncrasy of the Greenwich Village street pattern is more charming than the peculiar fluke of Waverly Place intersecting with itself, just south of Christopher Street, between Grove and Gay Streets. Named in 1833 after the recently-deceased Sir Walter Scott’s novel “Waverly” about the 1745 Jacobite Revolution in Scotland, Waverly Place is an east-west street from its eastern origin at Broadway, though known as Washington Square North between University Place and MacDougal Streets. But west of Gay Street it splits into two branches, with one continuing west a few yards and terminating at Grove Street, with another veering sharply to the northwest, and continuing onward until its abrupt end at Bank Street. This results in a single Greenwich Village block bounded by the intersection of Waverly Place, Waverly Place, Grove Street, and Christopher Street.

The Northern Dispensary, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

The Northern Dispensary, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

Adding to the curious appeal is the building which occupies this unusual block where Waverly Place meets itself. The triangular (trapezoidal, actually, if you count a chamfered corner) Northern Dispensary, erected in 1827, is one of Greenwich Village’s strangest mysteries. The building has been empty for more than 30 years but has a colorful past. Built on land donated by the city with the stipulation that it only serve the indigent poor who could not afford medical care, it was known as the “Northern Dispensary” because it was where such care was dispensed to those in need, at what was then the northern edge of New York. One of its most famous patients was a down-on-his-luck Edgar Allan Poe, who came in 1837 complaining of a winter cold.

From the 1960s through the 1980s it was a dental clinic, but it shut its doors when it refused to treat patients with AIDS. The Archdiocese of New York then purchased the property and sought to locate a hospice for people with AIDS in the building, but that plan was scuttled. In the late 1990s, the building was sold to William Gottlieb, who died a year later. His family is yet to develop or occupy the historic structure.

10. St. Luke’s Place

Numbers 3-9 St. Luke’s Place, via Wiki Commons

Numbers 3-9 St. Luke’s Place, via Wiki Commons

The southernmost street in the Greenwich Village Historic District is no doubt also one of its most picturesque. The one block of Leroy Street between Seventh Avenue South and Hudson Streets not only has a special name, but a special character, complete with and gentle bend in the street, a lyrical arrangement of Italianate houses built as an ensemble between 1851 and 1854, and a shaded park across the street.

The 15 brick houses with prominent brownstone trim, decorative ironwork fences, and grand stoops capped by neo-classical entryways, have sheltered some prominent residents over the years. The revolutionary Max Eastman lived at no. 11 in 1920, while Theodore Dreiser began writing “An American Tragedy” while living at no. 16 in 1923. “Gentleman” James “J.J.” Walker (for whom the park across the street, a cemetery in the 19th century, is now named) lived at no. 6 in 1926 when he was elected Mayor. The celebrated poet Marianne Moore lived at no. 14 in the 1920s, while the artist Paul Cadmus scandalized the art world in 1934 while living at no. 5 with his homoerotic painting “The Fleet’s In.”

The street gained further renown in 1967 when no. 5 served as the setting for the Audrey Hepburn suspense-thriller “Wait Until Dark,” and attracted even further attention in the 1980s after the exterior of no. 10 and neighboring houses were used as the setting for ‘The Cosby Show.’

RELATED:

- The oldest house in the Village? It’s not what you think

- Secrets of the St. Mark’s Historic District: From Peter Stuyvesant’s grave to the only real east-west street

- Off the grid: The little Flatiron Buildings of the Village

+++

For updates and more details about the Greenwich Village Historic District 50th anniversary and a full roster of events, click here >>

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid