15 things you didn’t know about the East Village

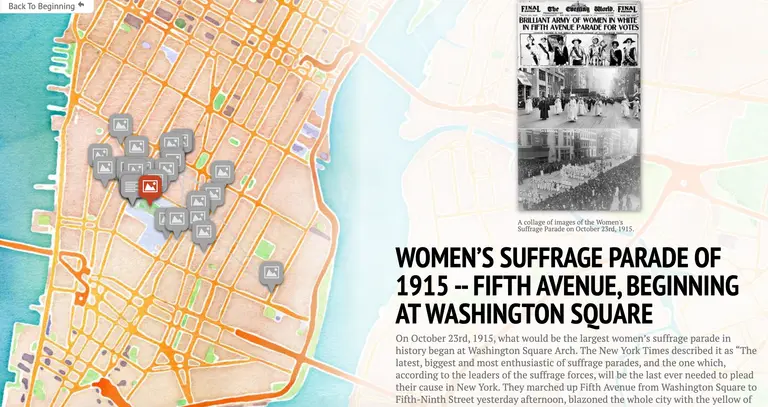

Earlier this month, GVSHP launched its East Village Preservation effort, releasing its new website “East Village Building Blocks,” which contains historic information and images for every one of the neighborhood’s 2,200 buildings. Of course, any neighborhood spanning five centuries of history and nearly 100 blocks will reveal some surprises when you scratch the surface. But the East Village’s story has some unique and unexpected twists and turns which are brought to light by this new online tool. From the birthplace of the shag haircut to four former homes of Allen Ginsberg to the first federally-subsidized public housing project in America, here are just a few of those you’ll encounter.

1. Movie palaces of yore

The East Village had a surprisingly large number of spectacular movie palaces, as well as some of our city’s earliest movie theaters. None of these former film houses still function as such, but some survive in altered form today, while others have been erased completely, with tools like Building Blocks the rare record of their existence. Some of the more prominent surviving examples include 144 Second Avenue, now the home of Veselka, 133 Second Avenue at St. Mark’s Place, once the home of the Negro Ensemble Company, which helped launch the careers of Angela Bassett, Laurence Fishburne, and Phylicia Rashad, and 105 Second Avenue, which functioned as the Loew’s Commodore Movie Theater for nearly four decades, after which it became fabled performance venue the Fillmore East, and later legendary gay nightclub The Saint.

No longer extant movie palaces include 98-108 Avenue A, which in 2016 replaced the old Hollywood Theater, 64-74 Avenue B, a banal brick building which was once a nursing home and was given a makeover for condo conversion in 2014, but which in 1966 replaced the stunningly opulent Loew’s Avenue B Movie Theater, and 110-112 Third Avenue, a glassy high-rise condo tower which in 2006 replaced the Variety Arts Theater, once one of New York’s first ‘Nickelodeon’ Theaters.

2. Filmed here

“Ragtime” being filmed in the East Village in 1980. Photo courtesy of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Image Archive, Carole Teller’s Changing New York, Part 4

“Ragtime” being filmed in the East Village in 1980. Photo courtesy of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Image Archive, Carole Teller’s Changing New York, Part 4

More than a few great movies were filmed in the East Village, though some pretended they were elsewhere. One example is the Martin Scorsese neo-noir classic “Taxi Driver,” key scenes of which were filmed at the then-menacingly run-down tenement at 226 East 13th Street. Another is “The Godfather Part II,” whose sequences which were supposed to take place in turn-of-the-last-century Little Italy were actually filmed in front of 520-530 and 521-531 East 6th Street in the East Village. And the East Village served as a stand-in for the early 20th century Lower East Side for the filming of the Oscar-winning 1981 film “Ragtime.”

3. Jazz and blues greats

The East Village may be more closely associated with musical genres like punk and psychedelic rock, but the neighborhood has a rich history of nurturing jazz and the blues, as well as those who produced it. Prominent examples include 412 East 10th Street, home of consummate Bluesman Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter in the 1940s and 151 Avenue B, the residence of jazz great Charlie Parker in the 1950s.

Legendary jazz venues in the neighborhood included Slug’s Saloon at 242 East 3rd Street, where jazz great Lee Morgan was shot and killed by his wife in 1972; the former Stuyvesant Casino at 140-142 Second Avenue (now the Ukrainian National Home), and the Five Spot Café at 200 East 5th Street, considered one of the great venues for jazz in the mid-20th century, where John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Ornette Coleman, and Billie Holiday all performed (the building was demolished and replaced with senior housing in 1983).

4. Disaster memorial

The synagogue today, courtesy of GVSHP

The synagogue today, courtesy of GVSHP

The General Slocum Ferry disaster was the greatest loss of civilian life in New York City prior to 9/11 and the second worst maritime disaster on U.S. waterways. One of two East Village memorials to the tragedy is located in front of what is now the Community Synagogue at 323-327 East 6th Street. The Synagogue was built in 1847 as the German St. Matthew’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, and it was largely its congregants who were on board the ill-fated ferry which caught fire and ran aground in June of 1904, killing over 1,000 mostly women and children. The disaster and tremendous loss of life helped precipitate the rapid transformation of this area from a largely German-immigrant to a largely Eastern European Jewish immigrant neighborhood, and in 1940 the present-day synagogue took over the building.

5. Birthplace of the shag haircut

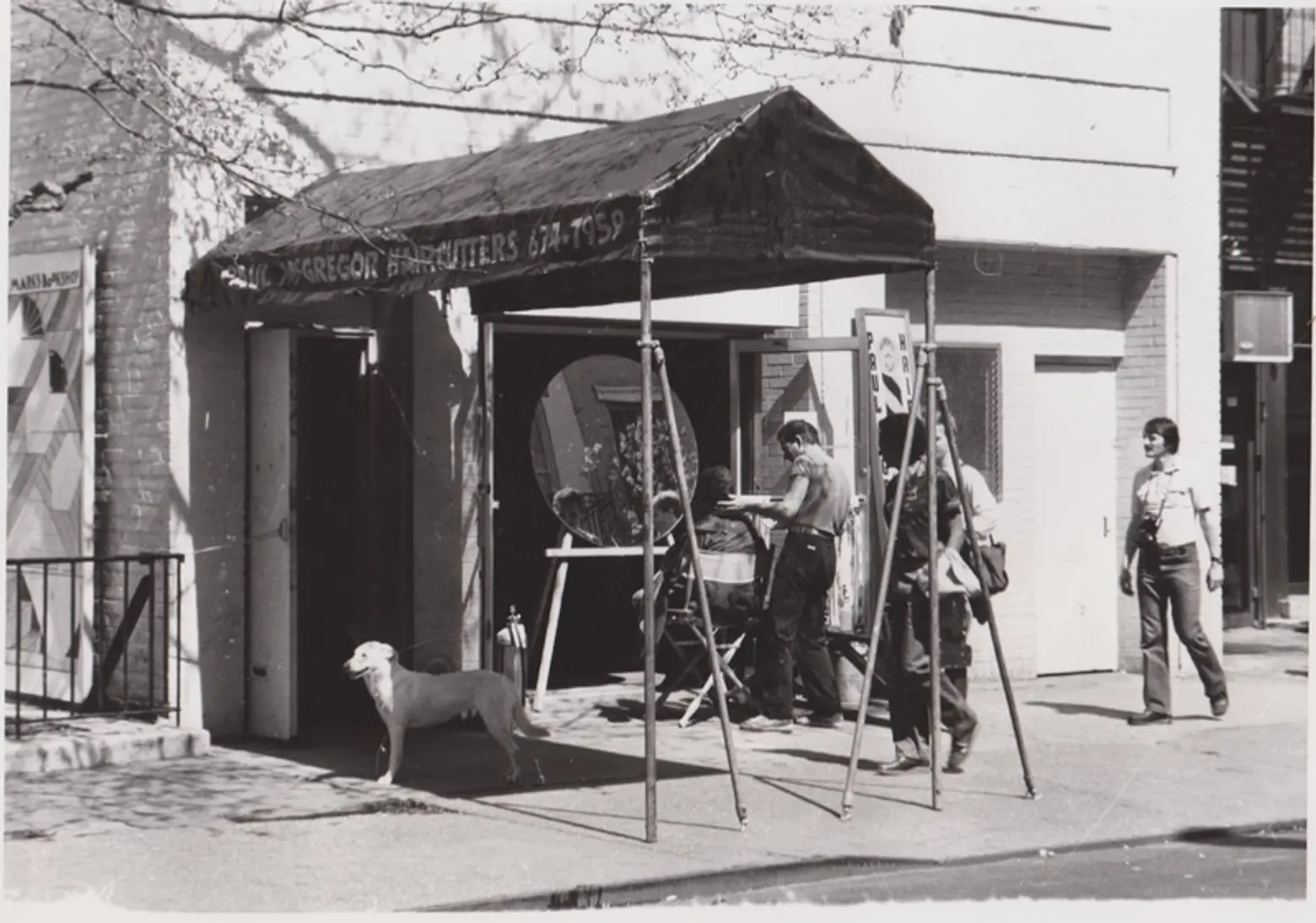

Paul McGregor’s salon at 15 St. Mark’s Place c. 1970. Photo courtesy of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Image Archive, Carole Teller’s Changing New York

The East Village is known as the birthplace of many trends and movements over the last 200 years. One of the more peculiar ones, however, and one of the easiest to pinpoint the origins of, is the shag haircut, which came to dominate both men and women’s hairstyles in the early to mid-1970s. Paul McGregor opened his haircutting salon at 15 St. Mark’s Place in 1965 and began giving clients what came to be known as a “shag” haircut for its messy, multi-layered appearance. Celebrities such as Jane Fonda, Warren Beatty, and Goldie Hawn made the haircut famous. Then, Warren Beatty made a fictionalized version of McGregor famous with the movie “Shampoo,” said to be based, at least in part, upon McGregor. After McGregor closed up shop the two-story former garage became a roller rink, a gay bar, and finally a rock club, before it had several stories added on top in 2004.

6. Tenement synagogues

Mezritch Synagogue today, via Wiki Commons

Mezritch Synagogue today, via Wiki Commons

Like the rest of the Lower East Side, the East Village is rich in “tenement synagogues,” houses of worship sandwiched onto narrow lots between tenements, built to serve the poor residents of the surrounding buildings. Though congregations were of modest means, some of the tenements had rich detail and ornamentation, expressing the congregants’ devotion to their religion and spiritual aspirations. Two of the most impressive are the neo-classical former Congregation Beth Hamedrash Hagedol Anshe Ungarn at 242 East 7th Street, an individual New York City landmark converted to residences in 1985 (after the building was abandoned for over a decade), and the Mezritch Synagogue at 415 East 6th Street, a building saved from demolition in 2008 and landmarked in 2012, and the only still-operating tenement synagogue in all of the East Village, albeit only on the ground floor (the rest of the building has been converted to residences to provide income for the tiny congregation). Other surviving former tenement synagogues can be found just down the block at 431 East 6th Street and across Tompkins Square at 317 East 8th Street (both converted to residences), and the near-twins at 636 and 638 East 6th Street, which now function as a Pentecostal Church and the Sixth Street Community Center, respectively.

7. Chameleon churches

The church at 345 East 4th Street today, via GVSHP

The church at 345 East 4th Street today, via GVSHP

Waves of immigration to the East Village over 200 years have helped give many churches a multi-faceted and ever-changing kaleidoscope of ethnic identities. For example, St. Ann’s Church at 112 East 12th Street was built as a Baptist Church in 1847, became a synagogue in 1856, became a Catholic Church in 1870, and an Armenian National Cathedral in 1983 before being turned into an empty entry pylon in front of an NYU dorm.

The Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Virgin Protection at 59-63 East 2nd Street was built in 1891 as the Olivet Chapel, a Protestant Church, by Josiah Cady, architect of the Museum of Natural History. St. Mary’s American Orthodox Greek Catholic Church at 121 East 7th Street had previously functioned as the First Hungarian Reformed Church, the Christian Orthodox Catholic Church of the Eastern Confession in North America, and the Church of St. Peter & St. Paul Russian Orthodox Church. The San Isidoro y San Leandro Orthodox Catholic Church of the Hispanic Mozarabic Rite at 345 East 4th Street (an unusual sect which follows the traditions of crypto-Christians in Moorish-occupied Spain) was originally constructed in 1891 for the Slovak and Hungarian Catholic Church of the St. Elizabeth of Hungary Roman Catholic Church, though by the 1930’s the church had become the home of the Carpathian Russian Orthodox Church of the Holy Trinity, and then the Russian Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas, during which time the present iron gate which showcases the coat of arms of the Russian Empire was added.

8. In-your-face drag’s origins

The Pyramid Club today, via GVSHP

The Pyramid Club today, via GVSHP

Drag has long roots in New York and throughout the world and is often a source of entertainment, humor, mysticism, or illusion. But starting in 1979 with the opening of the Pyramid Club at 101 Avenue A, drag took on a new in-your-face defiance, as traditional gender-bending combined with downtown punk attitude and performance art outrage on the tiny stage of this seminal East Village performance venue. The club eventually attracted the likes of RuPaul, Madonna, Nirvana, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Cyndi Lauper, Keith Haring, and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Though the ground floor space got its start as a German social hall, the building’s countercultural credentials go back to its years as the residence of model/singer Nico, the vocalist on the Velvet Underground’s first album.

9. A Radical “Servant of God”

Maryhouse today, via GVSVHP

Maryhouse today, via GVSVHP

Depending upon your penchants, the East Village may be seen as either a mecca for the sacred or the profane. One prominent East Village figure who combined both was Dorothy Day. The Brooklyn native immersed herself in a radical, bohemian lifestyle in Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side in the early 20th century, espousing communism, anarchism, and women’s liberation. However, by the 1930s she became involved with the Catholic Worker Movement, and soon dedicated her life to its radical social justice teachings combined with a religiosity which contrasted sharply with the communism and atheism of many of her former compatriots. She and her fellow Catholic Workers fought tirelessly for the rights of the downtrodden and exploited laborers and impoverished, and she remained dedicated to the cause until her death in 1980. The Catholic Worker can still be found in the East Village, at its Maryhouse at 51-55 East 3rd Street and the Catholic Worker House at 31 East 2nd Street. Day is currently under consideration for potential sainthood by the Catholic Church, gaining the interim title of “Servant of God.”

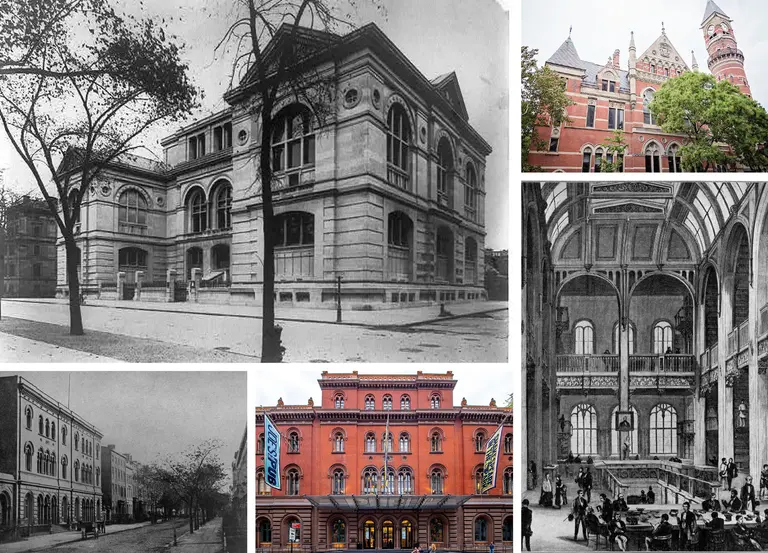

10. Oldest Libraries

The Ottendorfer Library today, via Wiki Commons

The Ottendorfer Library today, via Wiki Commons

The East Village is home to two of New York’s oldest and most distinguished libraries. The Ottendorfer Branch Library at 135 Second Avenue was built in 1883 as the first public library in what was then New York City, as part of the New York Free Library. The Tompkins Square Branch of the New York Public Library, built in 1904, was one of the very first Carnegie Libraries, a series of branch libraries built by the wealthy industrialist after the consolidation of Greater New York in 1898 and the reform movements of the late 19th and early 20th century intended to improve the lot of less fortunate city dwellers.

11. First Public Housing

First Houses, via GVSHP

First Houses, via GVSHP

The very first federally-subsidized public housing project in America can be found in the East Village, appropriately enough known as First Houses on 3rd Street and Avenue A. Opened in 1935, the development was radical not just because of the investment of federal monies, but the way in which the housing was constructed. Dozens of run-down 19th-century tenements where renovated and upgraded, every third building was demolished to add light and air, and communal back and rear yards were created in which residents could play and congregate. This became the very first development built and managed by the New York City Housing Authority, which now manages 326 housing developments across the five boroughs and houses more than 400,000 people, which would make it the 32nd largest city in the United States were it a separate municipality.

12. Ginsberg’s many homes

437-439 East 12th Street today, via GVSHP

437-439 East 12th Street today, via GVSHP

Few poets or artists are as closely identified with the East Village as Allen Ginsberg, who lived much of his adult life here at several locations and was a ubiquitous presence in the neighborhood until his death in 1997. From 1958 to 1961, he lived with lover Peter Orlovsky at 170 East 2nd Street, where he also wrote “Kaddish for Naomi Ginsberg” and helped William S. Burroughs write “Naked Lunch.” From 1975 to 1996, he lived at 437-439 East 12th Street, which overlooked the Mary Help of Christians Church (demolished) which he frequently referenced in his writings. In between, Ginsberg lived at the artists colony loft building at 405 East 13th Street along with Claes Oldeburg and Larry Rivers, among others, and the tenement at 406-408 East 10th Street.

13. Political Row

Political Row, via GVSHP

Political Row, via GVSHP

Passersby are often surprised to discover the row of charming, colorful early 19th century houses which line East 7th Street between Avenues C and D. But the 1840s houses at 258-270 East 7th Street are the last surviving intact remnant of what was once known as Political Row, a string of residences in former ship builders’ houses that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries housed some of the most powerful people and institutions in New York City politics, at a time when the Lower East Side ruled New York (in 1928, one of the Lower East Side’s own, New York State Governor Al Smith, became the first Catholic major party candidate for President, though he would lose to Republican Herbert Hoover). The buildings hold a place in literary history as well, as 264 East 7th Street was the home of Felicia Bond, who drew upon the house’s features for her classic children’s book “If You Give A Mouse A Cookie.”

14. A temple to labor

244 East 14th Street today, via GVSHP

244 East 14th Street today, via GVSHP

While the East Village is known for houses of worship and gathering places for labor, rarely do the two combine in the way they do at the East Village’s Labor Temple at 244 East 14th Street, a massive building constructed in 1924 by the Presbyterian Church. The innovative project was meant to create new ways for the church to interact with and support the community, while also generating new and much needed sources of revenue. When the church’s old building was declared unsafe in 1923, the church found supporters to help build a new building for the Labor Temple. It paid for the construction by renting out stores on the first floor and offices on the second. Additionally, the building housed an auditorium for 600, a chapel for 150, recreation space on the roof, a gymnasium inside, as well as classrooms, studios, offices, and meeting rooms.

It was open to any and all unions, and to unemployed laborers who could use it as a homeless shelter. Philosopher and writer Will Durant founded the adult education program called the Temple School at this site, which included a settlement house and church services. He ran the school until 1927 and developed the material he later used to write “Story of Philosophy,” published by Simon and Schuster in 1926, as well as “Story of Civilization,” published in 1935. Somewhat paradoxically, this shrine to the working class was designed by the architect of some of New York’s most iconic luxury apartment houses of the pre-war era, Emery Roth.

15. Squatter domicile saved by umbrellas

The Umbrella House today, via GVSHP

The Umbrella House today, via GVSHP

Few buildings capture the radical arc of life in the East Village in the late 20th century as well as the ‘Umbrella House’ at 21 Avenue C. Like many buildings in the eastern blocks of the East Village, by 1980 it was abandoned. But some urban homesteaders, determined not to see their neighborhood laid to waste, moved in, slowly turning the derelict building into a residence for dozens of people. This was no easy task with no utilities and a leaky roof, but the artists were both tenacious and inventive, using umbrellas to shield themselves from the elements as they slowly made repairs to the formerly abandoned building.

After more than a decade of residence, in 1995 the City sought to evict them from the building they restored. But they went to court and successfully sued to take formal legal possession of the building, the first time such a tactic was successful, and the building to this day remains an affordable co-op. The building has had heat, water, and electricity for some time, but in tribute to their early days as outlaws using whatever tools they could to survive, the artist-residents of the building for a while installed multi-colored and –patterned umbrellas on the 1899 tenement’s façade and fire escapes, giving the building the name “Umbrella House.”

To explore East Village Building Blocks, click here.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid