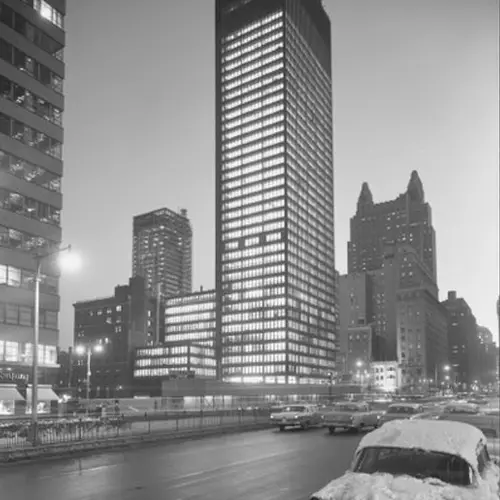

How Prohibition restructured NYC real estate and architecture (and built the Seagram Building)

NYC Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach watching agents pour liquor into a sewer following a raid; via Wikimedia

One hundred years ago, the United States Congress passed a temporary Wartime Prohibition Act banning the sale of beverages with an alcohol content of over 1.28 percent. The 1918 amendment later led to full-blown Prohibition, which wouldn’t officially end until the early 1930s.

Find it difficult to imagine a spirit-less New York? In 1918, many New Yorkers, including city officials, also had a difficult time imagining a New York without alcohol. After all, with alcohol banned, the future remained uncertain for an estimated 9,000 hotel and saloon properties. The city itself stood to lose roughly $18 million in tax revenues related to the sale of liquor. In the end, however, New York not only survived the Prohibition Era but, indirectly, had its architecture altered.

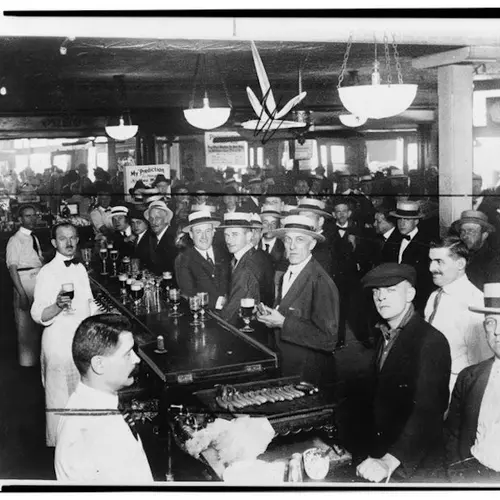

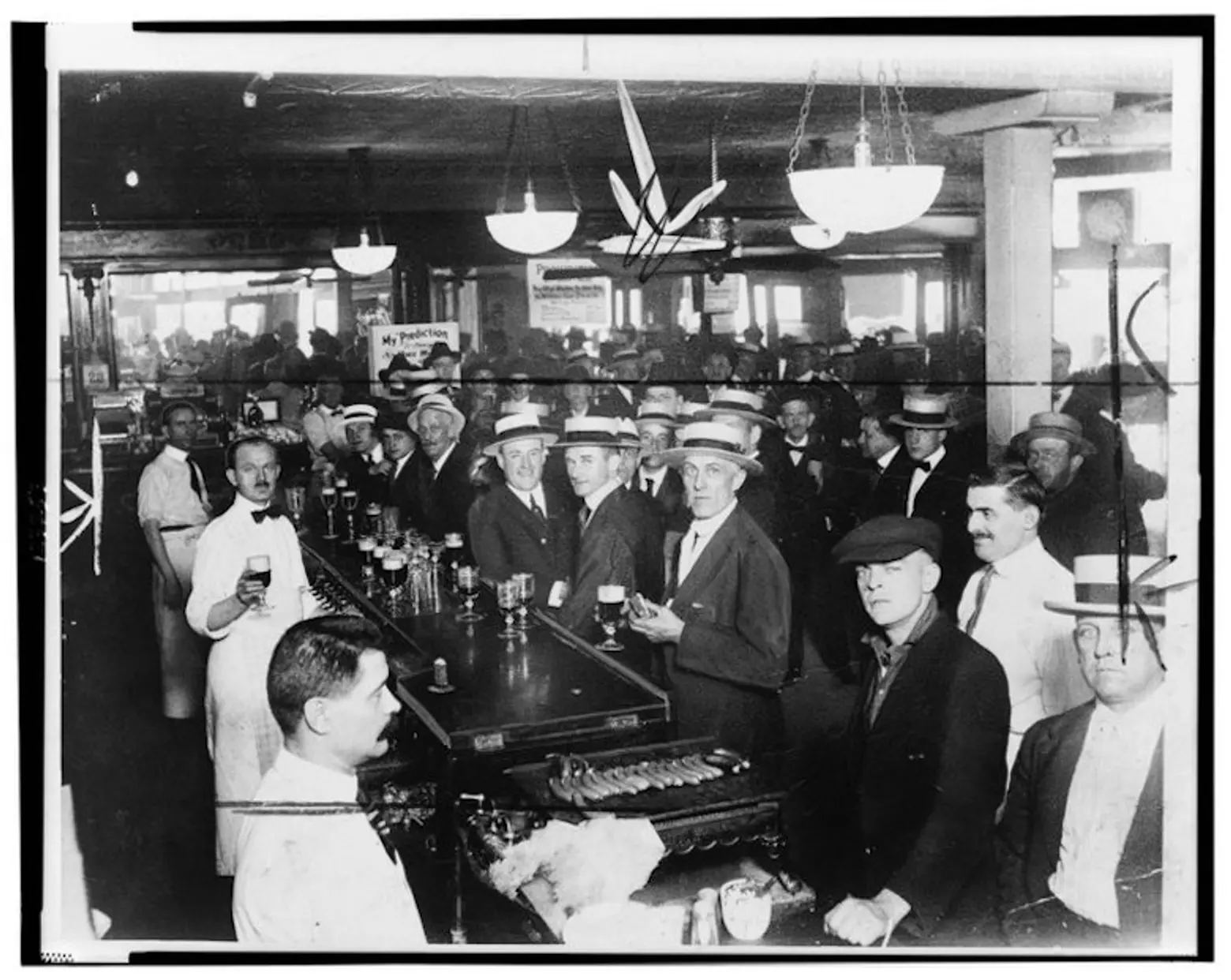

A crowded bar moments before midnight, June 30, 1919, when wartime prohibition went into effect NYC via Wikimedia

A blow to New York real estate

According to the most recent Federal census at the time, in 1918, there was more than $939 million invested in the state’s liquor industry—this figure included investments in brewing, malting, winemaking, and distilling, as well as saloons and hotels. As reported in the New York Times on Sept. 8, 1918, although the Food Administration’s order was nationwide, “the effect will be more noticeable in New York owing to the large amount of capital invested.”

Unsurprisingly, the alcohol ban raised immediate concerns among investors and developers. As one “prominent real estate operator,” who evidently did not want to go on record as being opposed to the government’s ban, told the New York Times: “This is a serious blow to New York City real estate.”

Among other concerns, the operator observed that many saloons and hotels occupied prime corner properties. Since it seemed unlikely that other retailers could afford such rents, his fear was that these prime properties might remain closed for a long period of time. But this wasn’t the only feared impact. Edward F. Doyle, chair of the Budget Committee of the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), also warned that as liquor taxes disappeared, property taxes would inevitably spike as towns and cities struggled to make up for lost revenues.

In NYC, drinking and real estate were also connected in another way—many brewers were also investors. Back in 1918, one local brewer, George Ehret, the producer of Hell Gate, owned more land titles than nearly any other city resident. He held title to approximately 200 parcels of land citywide, which may explain why his estate was still worth an estimated $40 million in 1927 at the height of Prohibition. The Peter Doelger Brewing Company also held many land titles back in 1918—the company reportedly owned approximately 100 land titles at the time.

In the end, many early concerns about Prohibition proved accurate. The loss of tax revenues, for example, had widespread economic consequences in the city. However, the Eighteenth Amendment, which came into full effect on January 19, 1920, prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating beverages but not their possession or consumption.

This meant that while Americans could no longer manufacture or sell alcohol, they could consume it, and this was good news for Canadian brewers, distillers, and distributors.

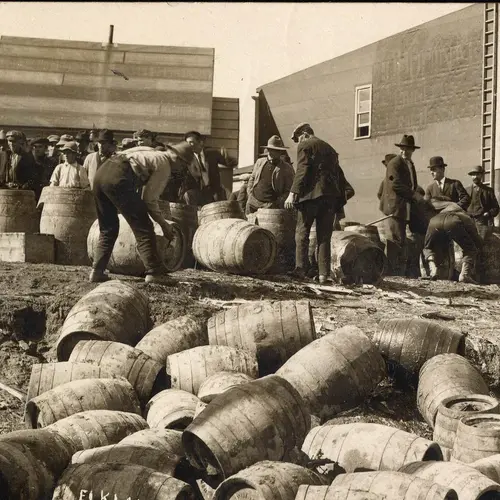

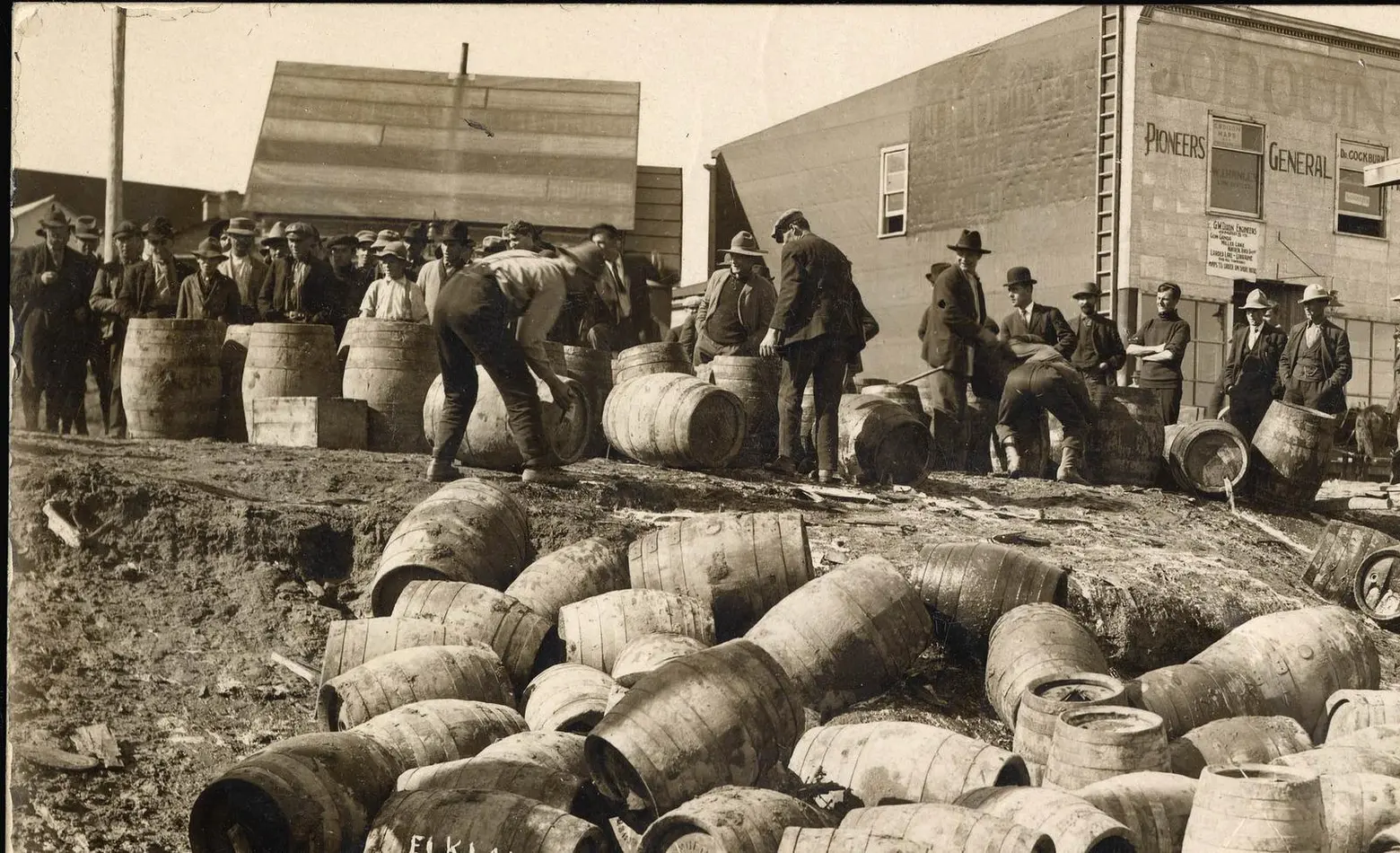

A police raid confiscating illegal alcohol in Canada in 1925

The arrival of Canadian bootleggers

As Prohibition shut down local breweries and distillers, local drinkers sought new sources. With beer, wine, and spirits still running freely in Canada, Canadians were well positioned to take advantage of Prohibition. There was only one problem: how to get alcohol into the U.S. without being caught.

As legend has it, bootleggers deployed many creative methods. On May 17 1922, the New York Times reported on a Montreal bootlegger who was caught only after crash-landing his plane at Croton-on-the-Hudson. While flying whisky across the border was somewhat unusual, the origin of the whisky was no coincidence.

An estimated 1.1 million gallons of Canadian whisky was shipped across the border in 1928 and 1929 alone and much of it came from one source: the Bronfmans of Montreal.

Via Wikimedia

How Canada’s first family of bootlegging shaped the NYC skyline

Thanks to U.S. Prohibition, Canadian bootleggers, especially the Bronfmans who would later purchase the Seagram Company, profited. Post-Prohibition, Samuel Bronfman would only say that he had sold a lot of whisky during Prohibition but remained reticent to talk about the legality of sales south of the border.

In 1935, however, when the U.S. sued the Canadian distillers for taxes and duties that they claimed were avoided during the Prohibition-era, Bronfman did pay half of the fine. Notably, there is no indication that the $1.5 million set him back. By then, his family’s wealth was so massive, they had even started to venture into other industries. In the end, Bronfman’s wealth combined with his daughter interest in architecture would ultimately radically change New York City’s skyline.

Bronfman established a holding company in 1951 for his children and Phyllis, by then known as Phyllis Lambert, acquired a 22 percent ownership stake. With a large percentage of her father’s wealth now in her control, Lambert started to make her own mark. In 1954, she moved to New York City to learn more about architecture. Eventually, she would graduate from the Illinois Institute of Technology.

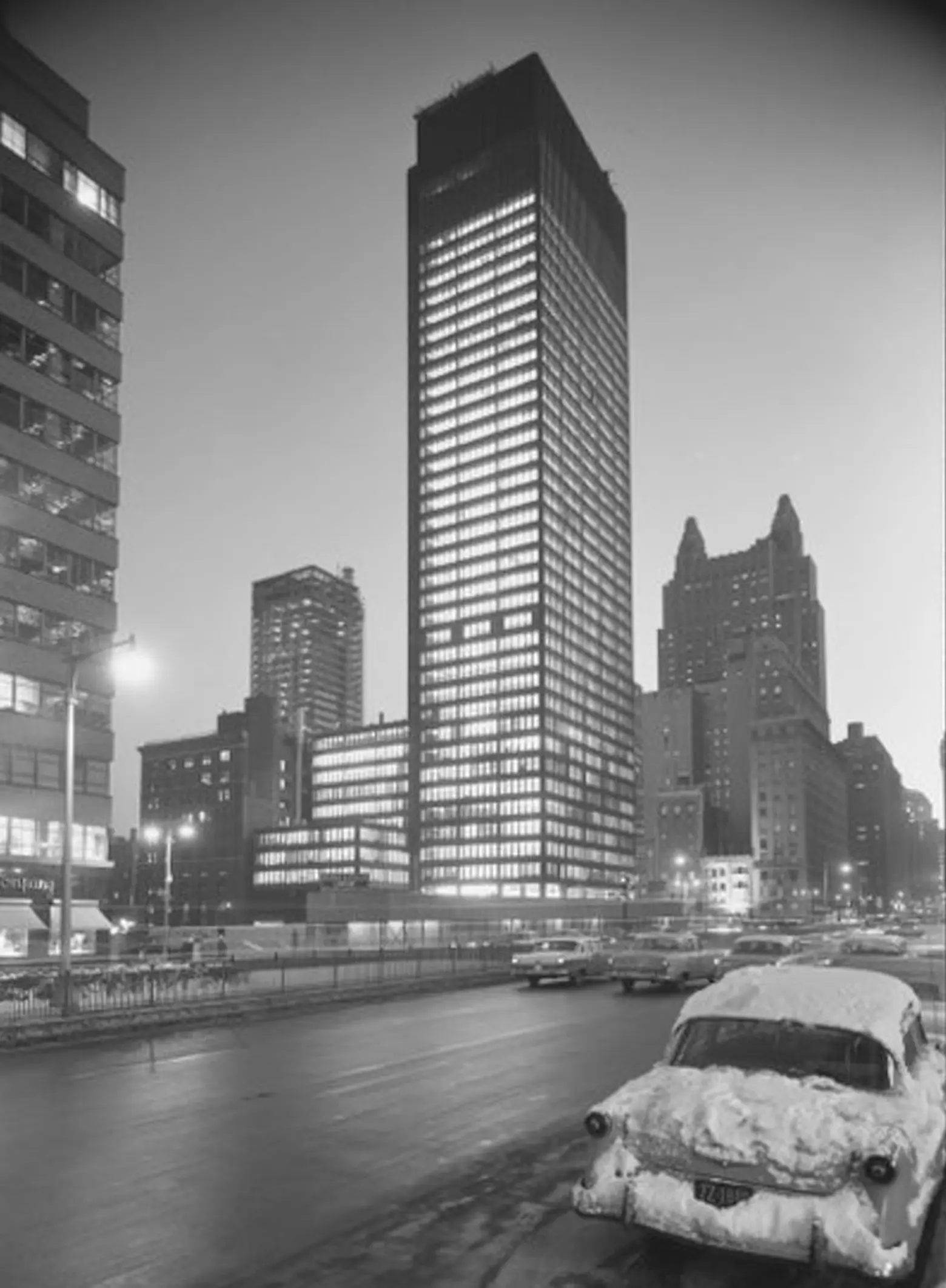

While Lambert trained as an architect and played a role in both the design and development of many buildings over the past six decades, her most notable intervention was arguably the decision to hire Mies van der Rohe to design the iconic Seagram Building at 375 Park Avenue.

By the time the Seagram Building was complete, the bold structure had rung up a $41 million bill, making it the world’s most expensive skyscraper of the era. The building also helped to usher in a new era of building design in New York City. Its minimalist exterior and the decision to construct it away from the street were controversial at the time but ultimately both of these design elements would heavily influence the future of New York City high-rise architecture.

While van der Rohe and Lambert’s combined vision is certainly to credit here, indirectly, the Seagram Building and its subsequent influence on the city’s architecture can be traced back to the era of Prohibition. It seems unlikely that Bronfman would have ever amassed his wealth and subsequently been able to pass along such a large fortune to his children, including visionary architect and developer Phyllis Lambert, without Prohibition.

RELATED: