When NYC collapsed: The rise and fall of America’s largest and grandest hotel

The Grand Central Hotel in the late 1800s, via Wiki Commons

In the mid-1970s, New York City was falling apart. Its finances, infrastructure, and social cohesion were, figuratively speaking, crumbling. But in one very tragic case, they were literally crumbling, too. And it all came tumbling down on August 3, 1973, when what was once one of the world’s grandest hotels (which had more recently become known for mayhem of both a musical and criminal sort) collapsed onto Broadway at Bond Street in Greenwich Village. From serving as the scene of one of the time’s most notorious murders to a connection to the National Baseball League, the Grand Central Hotel certainly had a grand history.

The Grand Central Hotel was built in 1870 at 673 Broadway in a grand Second Empire style with one of the city’s most elaborate mansard roofs. Its builder, Elias Higgins, and architect, Henry Engelbert, were also responsible for the Grand Hotel at 1232 Broadway and 31st Street, built just two years earlier. This landmarked structure still stands today and looks very similar to its now-departed Greenwich Village sibling.

When built, the aptly named Grand Central Hotel was the largest hotel in America, and one of the largest and most luxurious in the world. Its location on lower Broadway put it in the center of what was then an upscale shopping, business, and entertainment district.

When built, the aptly named Grand Central Hotel was the largest hotel in America, and one of the largest and most luxurious in the world. Its location on lower Broadway put it in the center of what was then an upscale shopping, business, and entertainment district.

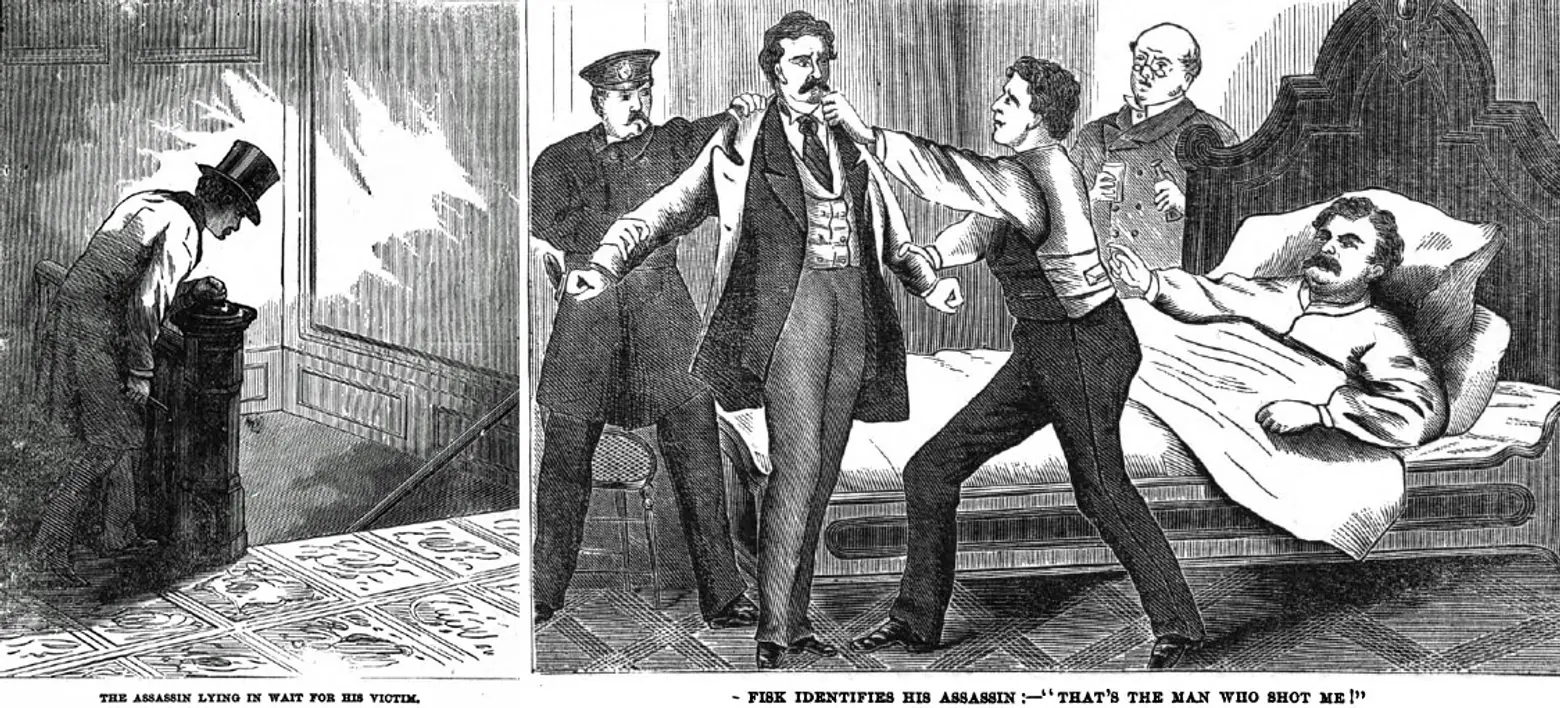

Cartoons depicting the Fisk murder in the Grand Central Hotel, from the 1872 book “Life, Adventures, Strange Career and Assassination of Col. James Fisk, Jr.”

The hotel made history, good and bad, from its earliest days. In 1872, “Diamond Jim” Fisk Jr., one of the most notorious robber baron financiers of the Gilded Age, was shot and killed on the hotel’s staircase by his former partner, Edward Stiles Stokes. The two had been engaged in a bitter lawsuit, and Stokes had recently fallen for Fisk’s mistress, Josie Mansfield, adding passion to their legal and financial dispute.

On a more wholesome note, in 1876 the National Baseball League was founded at the hotel when eight professional teams gathered there to form the association. This historic event was recalled at the hotel 49 and 75 years later when notable players including Ty Cobb, Cy Young, and Roger Hornsby, among others, gathered to mark the anniversary.

On a more wholesome note, in 1876 the National Baseball League was founded at the hotel when eight professional teams gathered there to form the association. This historic event was recalled at the hotel 49 and 75 years later when notable players including Ty Cobb, Cy Young, and Roger Hornsby, among others, gathered to mark the anniversary.

By the time of the 75th-anniversary event in 1951, however, the hotel’s glory days were long behind it. In the early 20th century, the area had already traded its luster for a bawdy mix of tenements, manufacturing lofts, and cheap entertainment venues, largely filled by Lower Manhattan’s booming immigrant population. But by the third quarter of the 20th century, the hotel and much of its environs had gotten downright unsavory. Now known as the University Hotel (for its proximity to NYU), it was the city’s largest “flophouse,” home to drunks, junkies, and drifters. In the first six months of 1972 alone, the hotel was the scene of 49 burglaries, 22 robberies, 18 drug-related crimes, seven petty larcenies, six felonious assaults, five grand larcenies, three rapes, and one murder.

Ironically, however, the hotel was undergoing a renaissance of sorts at the time, which many hoped would save it. While the residential portion of the structure remained squalid, in 1970 Art D’Lugoff, impresario of the iconic Village Gate Theater just a few blocks away on Bleecker Street (also located in a seedy SRO hotel, then known as the Greenwich, now the Atrium Apartments) announced plans for the Mercer Arts Center, which included six performance spaces in the lower floors of the formerly grand hotel. Envisioned as a sort of Lincoln Center for the alternative downtown art scene, it quickly gained tremendous popularity after it opened in December of 1971, on the eve of the aforementioned crime spree.

The center’s multiple performance spaces housed everything from contemporary theatrical productions to Shakespeare; poetry readings, dance performances, experimental film and video showcases. But it became perhaps most famous as a mecca, albeit fleetingly, for the burgeoning downtown early-punk scene, when CBGBs was still just a Bowery biker bar. The Modern Lovers, Suicide, and most famously the New York Dolls found a home there, with their raucous performances reverberating within the cavernous spaces throughout 1972 and the first part of 1973.

However, soon noises and vibrations of a different kind became a cause for concern. The Mercer Center operators reported cracks and shifting walls to the hotel managers, who claimed they were addressing them. The walls could be heard to “groan” in one of the theaters.

By the afternoon of August 3rd, 1973, the Mercer Arts operators urged that an engineer be brought in, but none could be found. By 5pm, bricks were reported to be falling off the walls of the theaters, which were quickly evacuated. Within 10 minutes, according to the New York Times, the building “felt like it was exploding.” The hotel collapsed entirely, spilling tons of debris onto Broadway, a mere 20 minutes before the evening’s first performances were set to begin. Had the collapse happened just slightly later in the evening, without the warnings signs having been heeded, the results could have been catastrophic. Nevertheless, four people died, and more than a dozen were injured. (See photos of the disaster here.)

It was later revealed that a wall in the basement of the hotel had been removed a few years earlier, which, with the constant rumbling of the subway underneath, likely led to the collapse. The remnants of the building and its neighbor to the north at 240 Mercer Street had to be demolished and removed. The University Hotel site remained vacant for nearly a decade until NYU built a law school dorm on the site, which remains there today.

As further evidence of New York’s ongoing collapse, just four months after the hotel’s undoing, a large chunk of the West Side Highway came crashing down just across town on Gansevoort Street in the West Village, leading to the eventual closing and demolition of the entire elevated roadway.

1973 was certainly a good year for New York falling apart.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED: