Brownstones and ballot boxes: The fight for women’s suffrage in Brooklyn

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia

Today, Brooklyn is home to all things avant-garde, but Kings County has always led the pack. Beginning as early as 1868, the women of Brooklyn established one of the first suffrage organizations in the country and began advocating for women’s enfranchisement and political equality. The “wise women of Brooklyn,” as they were lauded in suffrage literature, made some of the foremost contributions to the movement. From the Silent Sentinels, who organized the first March on Washington, to the African American women who established the nation’s first suffrage organization by and for Black women, Brooklyn was home to extraordinary advocates. Here are eight badass Brooklynites who brought us the ballot.

1. Anna C. Field, brought suffrage to Brooklyn with a BAM

The suffrage movement in Brooklyn really did begin with a Brownstone and end with a Ballot Box. That brownstone, 158 Hicks Street, was home to Anna C. Field (1822-1912), Brooklyn’s original suffrage pioneer. Field held the inaugural meeting of The Brooklyn Equal Rights Association in her home in the fall of 1868. That evening, about 20 men and women who had been part of the abolitionist movement, gathered to throw their support behind “a new outlet in the cause of justice:” Women’s Rights. The Organization’s stated goal was “the promotion of the educational, industrial, legal and political equality of women, and especially the right of suffrage.”

This was Brooklyn’s first suffrage association, and one of the first women’s groups in the nation. When the Association formally organized in May 1869, it burst onto the political scene with a BAM: on May 14th, Anna C. Field presided over a marathon meeting at the Brooklyn Academy of Music that began at 10 a.m. and lasted until 7:30 p.m. and included some of the most prominent reformers of the day. In 1883, the group was renamed the Brooklyn Woman Suffrage Association. Through monthly meetings at 155 Pierpont Street, its members worked to help women secure legal rights to their children, their wages, and their property, and successfully advocated for female police officers in station houses, and women on the Brooklyn Board of Education. In fact, three of the five women appointed to that board in 1893 were members of the Association.

Reverend Celia Burleigh via Wiki Commons

Reverend Celia Burleigh via Wiki Commons

2. Reverend Celia Burleigh, spread the gospel of suffrage

Celia Burleigh (1826-1875) was the first woman in the United States to be ordained as a Unitarian minister. She got involved with the women’s movement in 1868, when women journalists were denied entry to a New York Press Club event honoring Charles Dickens, on the grounds that their presence would make the event “promiscuous.” In response, she became one of 12 founding members of Solaris, the first professional women’s organization in the United States. The following year, she was elected the first president of the Brooklyn Equal Rights Association. At one of the group’s meetings at BAM that year, she expressed her belief in every person’s right to their individuality, asserting that, “the object of the government should be securing to every human soul the right to make good on the faculties of itself.” Suffrage was part of that goal, she said because suffrage held “the promise that [every woman] would one day belong to herself, live her own life, think her own thoughts and become a woman in a better sense than she had ever yet been.”

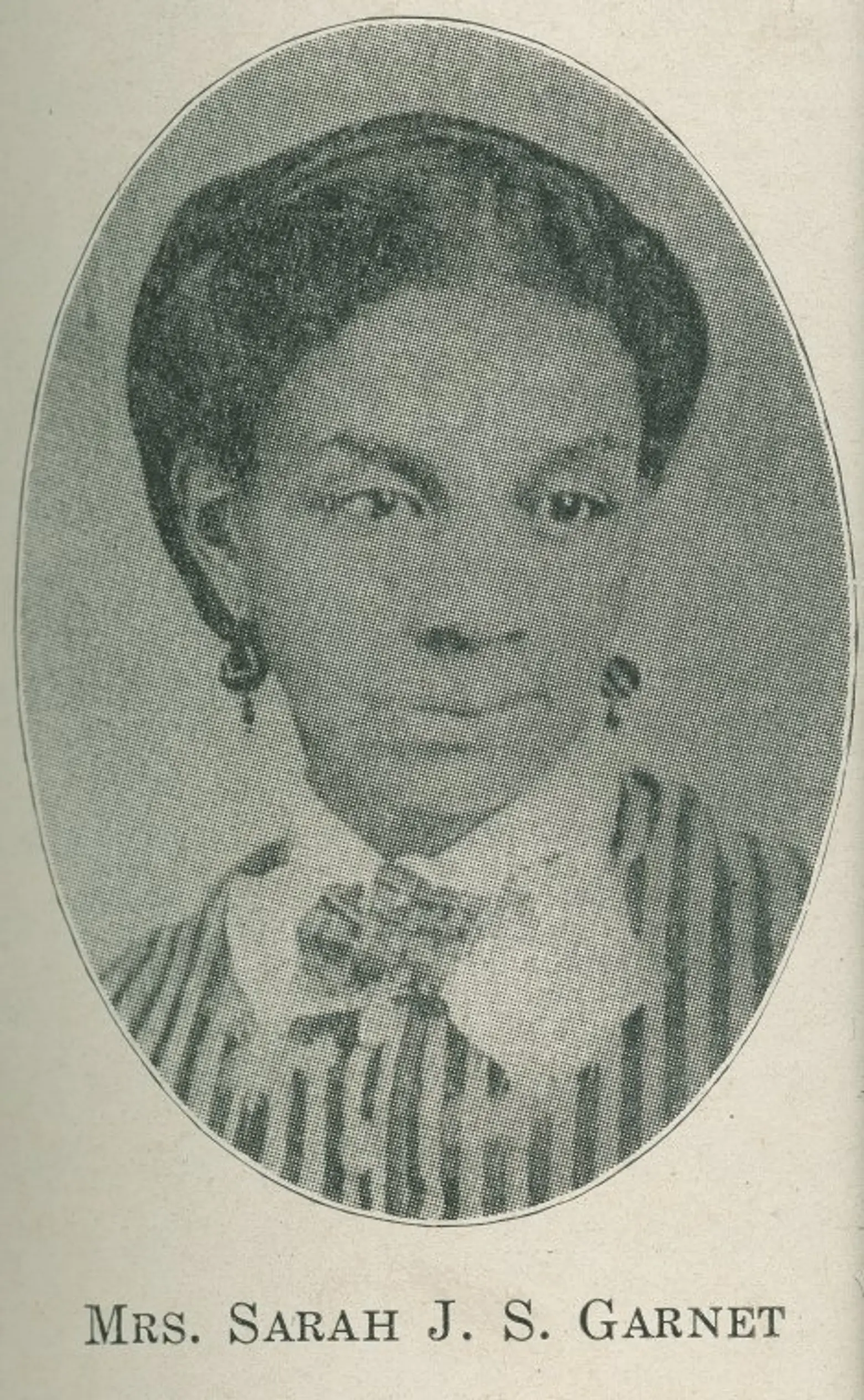

Sarah Smith Garnet via Wiki Commons

Sarah Smith Garnet via Wiki Commons

3. Sarah Smith Garnet, a principled principal Sarah J. S. Garnet (1831-1911), was born into a family of leaders. Her father, Sylvanus Smith, was one of the founders of Weeksville, a free Black community in what is now Crown Heights; her sister, Susan Smith McKinney Steward, was New York’s first female African American physician. She became the first female African American principal in the New York City public school system and founded the Equal Suffrage Legal of Brooklyn in the late 1880s. The League was the first suffrage organization in the country founded by and for black women. In its early years, the League met in the back of Garnet’s seamstress shop in Brooklyn, then relocated to the YMCA on Carlton Avenue. Soon, African American Women’s suffrage organizations proliferated in Brooklyn. For example, the Garnet sisters worked with a group of African American women to create the Woman’s Loyal Union of New York and Brooklyn in 1892. Because of her service to equal suffrage, Smith was also elected superintendent of the Suffrage department of the National Organization of Colored Women.

Victoria Earle Matthews in 1930, via NYPL

Victoria Earle Matthews in 1930, via NYPL

4. Victoria Earle Matthews, the great awakeningVictoria Earl Mathews (1861-1907), who was born into slavery in Georgia and went on to become one of the most prominent black activists in the country, served as the Woman’s Loyal Union of New York and Brooklyn’s first president. She began her career as a journalist while in her teens, and went on to publish fiction and deliver lectures such as “The Awakening of the Afro-American Woman.” In addition to her leadership of the Union, she co-founded and chaired the National Federation of Afro-American Women, and sat on the Executive Board of the National Association of Colored Women. After her only son died at the age of 16, she became deeply invested in helping young people. In 1897, she founded the White Rose Home for Working Class Negro Girls, also known as the White Rose Mission, on 86th Street in Manhattan.

5. Cornelia K. Hood, the Brooklyn Portia

Cornelia K. Hood (1868-1917), lawyer, magazine editor, and suffragist graduated from NYU Law School in 1893, part of the first class of women in the nation to do so. She earned the nickname The Brooklyn Portia because she pioneered a series of talks at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences in 1894, known as Law Lectures for Women. After her death, friends and notable Brooklyn residents established the Cornelia K. Hood Memorial Endowment for Law Lectures for Women.

Hood’s interest in the law was part of her advocacy for women’s rights. She argued, that, “the laws of the land do not protect the natural rights of women sufficiently; nor do they seek to place her on a mental or moral equivalent with man. Women must bring about this elevation, which they sorely need. To do this, they must organize, and the legal advisors among themselves are indispensable.” Fittingly, in 1894, she became president of the Kings County Political Equality League, and the Kings County Suffrage Association. The League held its first meeting at the Long Island Historical Society on Pierrepont Street, which is now the Brooklyn Historical Society.

Maria Coles Perkins Lawton, by source (WP:NFCC#4), fair use

Maria Coles Perkins Lawton, by source (WP:NFCC#4), fair use

6. Maria Coles Perkins Lawton, organizer and orator

In 1910, members of the Kings County Suffrage Association established the Harriet Beecher Stowe Equality League of Kings County, and elected Maria C. Lawton (1864-1946) president. After graduating from Howard University, Lawton became a public school teacher and married the minister and mathematician William Lawton. In 1892, the Lawtons moved to Brooklyn, and Maria Lawton began a 20-year career in journalism with the Brooklyn Daily Standard Union. By 1897, she embarked on a lecture career, speaking on issues of race, gender inequity, and children’s education. In 1912, she was elected state organizer for the Empire State Federation (affiliated with The National Organization of Colored Women’s Clubs) and served as president of the Federation from 1916-1929. In 1924, she went to work at the national level, representing New York at the Labor Conference for Women, then turning her efforts to the Republican Party. That year, she was appointed director of the eastern division of the Republican National Convention and endorsed Calvin Coolidge for President.

Lucy Burns in 1913, via Wiki Commons

Lucy Burns in 1913, via Wiki Commons

7. Lucy Burns, the silent sentinel

Born and Raised in Brooklyn at 904 President Street, Lucy Burns (1879 – 1966) founded National Women’s Party and became one of the foremost advocates for women’s suffrage during the early 20th century. She began her career in Brooklyn, teaching English at Erasmus Hall Academy, then went to Europe to continue her own studies. There, she got involved with British militant suffrage and Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union. At a British police station, she met fellow American suffragist Alice Paul. Both Alice Paul and Lucy Burns were arrested several times for demonstrating with the WSPU, and they returned to the United States in 1912 to continue the fight at home.

Elected head of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association’s Congressional Committee, Paul and Burns organized the Women’s Suffrage Procession of 1913 held in Washington the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. That year, the pair created their own suffrage organization, The Congressional Union, which became the National Women’s Party in 1916. As part of the NWP, Burns organized “suffrage schools” to teach other women how to campaign and lobby for the vote. In January 1917, the National Women’s Party organized the first protest in front of the White House. Suffrage advocates stood silently holding banners and were known as the Silent Sentinels. When the 19th amendment passed, Lucy Burns returned to Brooklyn, where she lived for the rest of her life.

Inez Milholland in 1913 at the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., via Wiki Commons

Inez Milholland in 1913 at the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., via Wiki Commons

8. Inez Milholland, suffrage queen and movement martyr

Inez Milholland, (1886-1916) the society girl turned labor lawyer who became the Suffrage Movement’s Joan of Arc, was born to a progressive and prosperous family at 179 Brainbridge Street. Her father, John, helped found the NAACP and the Men’s League for Women’s suffrage. Inez carried that political pedigree with her to Vassar. When Vassar’s president forbid discussion of women’s suffrage on campus, Mulholland led a group of students and suffrage into a graveyard adjacent to campus. Under the motto, “Come, Let us Reason Together,” the Vassar Votes for Women Club was formed. Soon, two-thirds of the campus was involved, and Milholland held meetings on both Suffrage and Socialism.

Milholland continued to carry the banner of the movement. After graduating from NYU Law School in 1912, she devoted herself to labor law, anti-militarism, and universal suffrage. In 1913, she led the Women’s Suffrage Procession, sweeping up Pennsylvania Avenue on a White Horse, cloaked in a flowing cape and sporting a tiara. Behind her, five thousand women marched with floats, bands, and cavalry brigades, all making the “Great Demand” for universal suffrage. In 1916, Milholland began a lecture tour for the National Women’s Party. At an event in Los Angeles, she collapsed. Her last reported words were, “President Wilson, how long must women wait for liberty?” At just 30 years old, it seemed that Inez Milholland had given her life for suffrage, and she was honored as a martyr of the movement.

+++

RELATED:

- Celebrate Women’s History Month with these 15 feminist shops, events, and exhibits in NYC

- 15 female trailblazers of the Village: From the first woman doctor to the ‘godmother of punk’

- MAP: Explore the women’s suffrage movement through the lens of NYC landmarks

- Parks Department approves Central Park’s first monument to historic females