Elizabeth Jennings: The woman who helped desegregate NYC streetcars

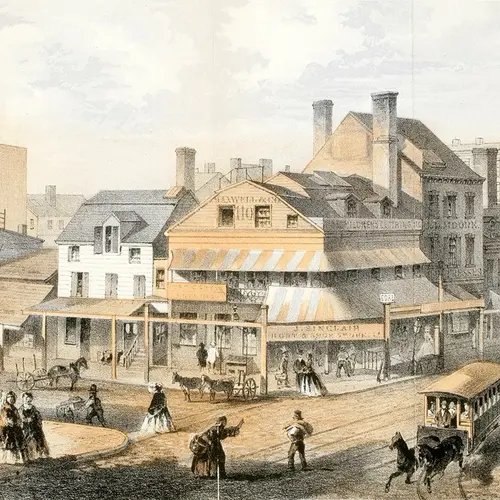

The corner of Pearl and Chatham streets, where Jennings hailed the bus. Photo via New York Historical Society

In 1854, 99 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to white passengers in Alabama, another brave African American woman forever changed local transit with her bravery. Elizabeth Jennings is not a household name, or even well-known, but her brave refusal to cow to 20th-century America’s racist customs and fight for her rights is historic, and the results of her actions have rippled down over the decades.

Elizabeth Jennings in 1895 via Wiki Commons

Elizabeth Jennings in 1895 via Wiki Commons

Jennings made history on a summer Sunday in 1854 when she and her friend Sarah Adams were running late for church at the First Colored American Congregational Church in lower Manhattan, where Jennings was an organist. The summer prior, the Third Avenue Railroad Company had put steel rails into select Manhattan streets and begun running a street railway service, the Third Avenue Railroad Company, according to the Historical Society of the New York Courts. Some cars bore signs stating, “Negro Persons Allowed in This Car,” but the first horse-drawn streetcar to approach Jennings and Adams did not. Despite this, the two black women boarded. The conductor, while initially letting them on, promptly told the pair to get off, “first alleging the car was full; and when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence,” a March 1855 copy of New-Lisbon Ohio’s Anti-Slavery Bugle recounts. The paper goes on:

She saw nothing of that, and insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted, they got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, soiled her dress, and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered around, but she effectually resisted and they were not able to get her off.

Having been incapable of removing Jennings himself, the conductor drove the bus on until he saw a policeman, who he sought to help remove her, which they did.

Clearly not one to go down without a fight, Jennings immediately sought the help of her family in seeking justice following the traumatic incident. The very next day, a letter she wrote telling of her experience was read in church, and then subsequently published in full in both the New York Daily Tribune and Frederick Douglass’ Paper. In the letter, Jennings describes how she told the bus driver, “I was a respectable person, born and raised in the city, that I did not know where he was from and that he was a good for nothing impudent fellow for insulting decent persons while on their way to church.”

Jennings’ father, Thomas L. Jennings – America’s first known African American patent-holder – secured a white lawyer who had only recently been admitted to the bar but would go on to become president in 1881. The young Chester Arthur won the case the following year, 1855, with an all-male, all-white jury awarding Jennings $247.50 in damages and costs, New York Courts reported. As a result of the trial, the Third Avenue Railroad Company immediately desegregated its services, a massive win. Specifically, Brooklyn Circuit Court Judge William Rockwell ruled that “under the law, colored persons, if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the right to ride the streetcars,” and could not legally be disallowed onto a car, according to New York Courts.

Elizabeth Jennings’ actions and bravery had made a momentous impact. The opening paragraph of the Anti-Slavery Bugle article about her case reads: “The hardships and insults so long suffered by the colored people of this city, in consequence of the general refusal of omnibus and railroad proprietors to permit them to enjoy equal rights as passengers, are, we hope, nearly at an end.” The decision, the article goes on, “places that class of our citizens upon an equality with all others.” The piece’s title is the moving “Rights Of Colored People Vindicated.”

By 1865, all of New York City’s transit system had been desegregated.

At the time of Jennings’ violent removal from the bus, she was 24 years old and a schoolteacher. Later in life, she would go on to start one of New York’s first kindergartens for black children on her 41st Street home’s first floor. In 1901, at the age of 74, Elizabeth Jennings died in that home.

Well over a century after her death, a group of elementary school students at the Lower East Side’s P.S. 361 learned about Elizabeth Jennings and organized to commemorate her with a street sign. A successful campaign by the children yielded the Elizabeth Jennings Place street sign and co-naming of one block of Park Row in 2007. “We actually took a stand in the world for what we thought was right,” one student told Women’s eNews Inc of the sign. “She’s an unknown hero that helped our state,” said another.

RELATED:

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Great story! One point, this occurred in the 19th, not 20th century.